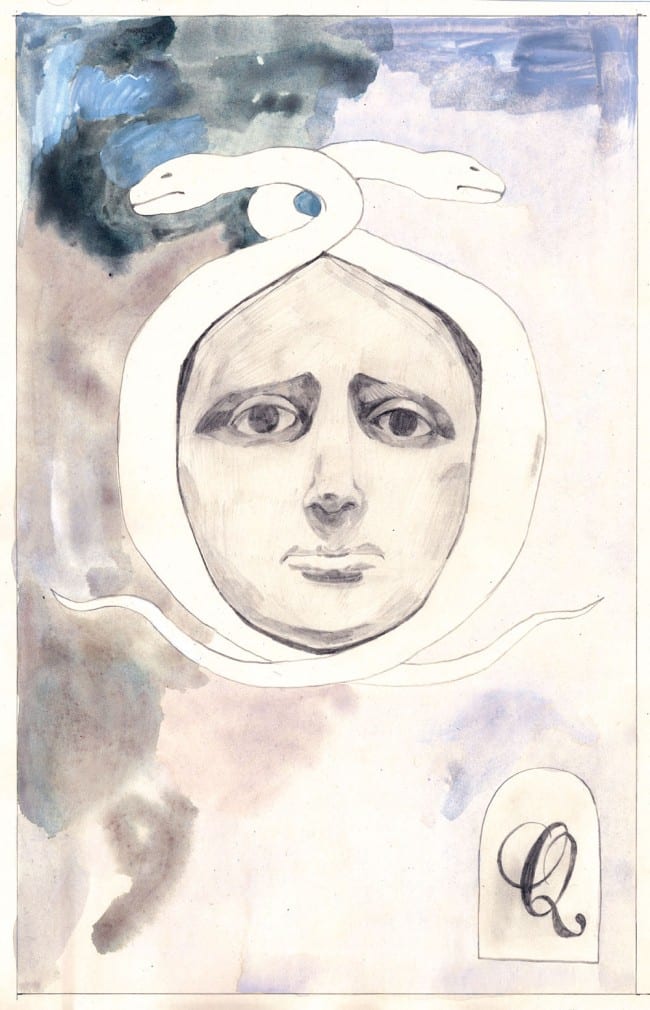

I almost didn't want to interview Aidan Koch, since so much of the power of her elliptical comics stems from things left unsaid. Gossamer pencil rendering, conspicuous gaps in both image and text, a tendency to put just enough on a page and no more—these techniques give Koch's comics a sense of whispered mystery and melancholy. Indeed, the trajectory of this 24-year-old Olympia native's work has taken her from comparatively straightforward, meticulously penciled black-and-white slice-of-lifers—including many of the comics available on her website and her book-length debut, The Whale—into more inscrutable color work—the cryptic Grecian imagery of the broadsheet-format Q and her Xeric-winning story of mental illness (I think), The Blonde Woman, previously serialized at Study Group Comics. It feels a shame to shatter the quietude of the comics themselves.

But I learned first-hand that Koch is as garrulous, amicable, and confident a talker about her comics as the comics themselves are restrained and gestural: After introducing myself to her at this fall's Small Press Expo, I probably stood and talked with her about her work at her table for half an hour, and was repeatedly impressed by her articulate insights into both her comics and the process behind them. (As a 2009 graduate of Portland's Pacific NW College of the Art, she's surely no stranger to speaking about what she's up to.) Meanwhile, Koch's two most recent releases—the life-drawing collection Field Studies, published by Jason Leivian's Floating World imprint, and the crime comic (!) Red Sands, a No Country for Old Men-like story of desert death drawn during a residency in Utah—take her work back to the somewhat firmer penciled ground of her earlier efforts.

This seemed like an ideal time to take stock of Koch's work to date. Sure enough, Koch's thoughts on how she constructs her comics, what they communicate to their readers, who those readers are, and the kinds of comics she doesn't like having created, filled in the gaps, all right, but in a way that only increased my appreciation for what she does and how she does it.

Sean T. Collins: When I think of how most cartoonists approach a page, the picture in my head is one of addition: piling mark upon mark until the page is full. With you, it's very different: I picture subtraction, as if somewhere out there there's a maximalist version of each page that you slowly whittled away at until only the elements you felt were necessary remained. I know it's unlikely that that's literally how it works for you, but is that basic image in any way reflective of your method?

Aidan Koch: I think I definitely consider "what is the minimum information needed to move the story along?" Unlike traditional cartooning, it's not a thumbnail to pencil to ink to color process. It's not particularly linear at all. Especially when I work in color—I lay everything down together switching between pencil and gouache as needed to fill in the space. It's true, though, often after I've done that, I go back in with white paint or remove parts that don't work or move things around. I very rarely plan a page ahead of time, so composition has to be adjusted while I work.

Have you ever given much thought to a more planned-ahead approach?

Sure. But to be honest, I don't feel like I'm really trying to tell stories. I don't care if people don't totally "get" what's going on. I don't care much about composing some kind of epic narrative. To me, that would really take most of the fun out. The idea of slaving away at something that's already completed on a mental level, that I am basically transcribing ... seems very tedious. I have pages full of notes on subjects and themes and dialogue and scenes that I can start from or sometimes I just start from a found image or photo that is compelling. Of course, I spend many hours working on pages that go nowhere, but it's more engaging to me. There's a Michelangelo Antonioni quote that when I first read it, I was blown away because it is exactly how I approach comics: "I never discuss the plots of my films. I never release a synopsis before I begin shooting. How could I? Until the film is edited, I have no idea myself what it will be about, and perhaps not even then. Perhaps the film will only be a mood, or a statement about a style of life. Perhaps it has no plot at all ... Things suggest themselves on location and we improvise."

Continuing on that point, I like the way your comics make me feel like I have to work at understanding them. These gaps and erasures that I picture when I think of how you make comics -- it's as though the meaning of the work is located in those holes, and it's up to me to fill them in. I'm not just talking about narrative, plot-based information, although in The Blonde Woman at least that seems a big part of it, but even the basic matter of how I'm supposed to feel when I put the comic down.

It's very interesting to hear how other people end up interpreting my comics. I mean, when I am working on them, I have a pretty clear vision and kind of lose track of how they might be read into differently. What I've found though is that even if they don't understand the exact sequence of events the tone definitely translates. There are a couple people I check in with while working on a project just to make sure my intentions haven't become too convoluted. I think the process I work in is probably what you are referring to. I am mostly developing the story as I draw, not working from some overarching guide, so everything you feel visually developing the world and narrative is as much for you as for me. Generally I have a tone or idea I want to convey, so those gaps allow me to manipulate the narrative as I work. If you can't tell, I operate in a very loose fashion.

Now that I think of it, The Whale's central device, on both plot and visual levels, is a gap, an erasure: The protagonist's significant other died, and she's thinking about her life around that absence; the significant other "appears" in faint, unfinished pencil, sometimes even the target of a word balloon's tail, drawing attention to his/her erasure from the world.

And it's interesting because I never purposefully employed an "erasure-effect" per se. Whenever you notice the traces of things missing, its because I manually removed them from her world after giving them to her. They didn't work.

Are you content with tone coming through even if the transmission of the narrative is incompletely received? Is the tone the important thing to you?

Oh absolutely. I mean, think about the idea of studying literature and the hundreds and thousands of students that have to pull theses and hypothesize about symbolism and undercurrents. I think it's fair to say that sure, those authors probably didn't intend the majority of what people speculate, and yet we recognize it as a valid undertaking. I think what's important is what the author does give us is a basis or guideline to such speculation. I'd much rather create work that's dynamic and compelling than overly explanatory or simply "readable." In comics especially, there is so much the artist has to work with in their favor between the written, visual, and sequencing. It's kind of like how film is to photography, comics are to drawing/painting. It's about the immersive experience.

I'm not sure why that answer made me think to ask this ... actually, that's not true, it's because in my case the more comics I read, the more I realized I was responding to tone rather than story, in much the same way I respond to music for its tone more than its lyrics, and started valuing that in what I read and what I wrote. Anyway: Who are your big influences, in comics or otherwise?

I don't actually read comics a whole lot, and especially didn't when I first started creating comics. Mostly, I pull from literature and fine art. My favorite artist of all time is Odilon Redon. From there you have the likes of Degas, Matisse, Balthus ... As for more modern: Hockney, Luc Tuymans, Klara Kristalova ... My all-time favorite writers would probably be Simone de Beauvoir and Ernest Hemingway. Feminine/masculine. Hah! The people whom I've taken a more stylistic interest in would be like Anaïs Nin, Gabriel Gárcia Márquez, Milan Kundera, Lydia Davis, Sherman Alexie...

Color is taking an increasingly prominent role in your work. It's obviously important for the title character in The Blonde Woman -- it marks her as a vivid presence in the world, it metonymizes her for the other characters who spend so much time worried about/irritated with her, it occasionally drops out -- but, I think, even more so in Q, where the orange commonality between the pegasus's wings and the harpist's arms is pretty much the only tool you give us for making a connection between them, and making emotional sense of that connection.

Using the word "tool" is very appropriate. In the way that I like to employ a variety of symbols, color is one more tool to carry the reader. Carry them to what conclusion ... is up to them. I think it's exciting though, to develop layers in which people can explore deeper as they re-read it. The Blonde Woman has a lot of little cues that I was really excited about through the jumps in time to the jumps in reality and between characters. In Q, I was much less concerned with the reading, though it's there. It was more of an overall exploration into employing some new techniques and matter. I think the connection that's there, though, is important. Although I'm interested in fully abstracted comics, I'm more intrigued in how I can use it within a narrative context or structure.

How different is working in color versus working in black and white for you? At first glance it seems color gave you license to pare back the amount of linework you're doing...

I still love working in pencil a lot. Because it's such a precise medium, though, I can get caught up a bit in realism. Color has offered me an escape from that. It changes the type of information I have to provide to create a scene while not distancing myself from how I want things to look stylistically. So yeah, not as much line work. I did a piece based off of Degas paintings for an issue of Kus! where I think the only pencil I used was for the panel outlines—it's just a color field. I love that piece. Of course, in that case it's totally appropriate, but it's the same basic approach I used for the pegasus panels in Q. It took a while for me to start working more in color mostly because I couldn't see there being many options for printing. When starting work I still feel the pressure to automatically consider how to make things cost-effective (ie b/w), which is unfortunate. I definitely feel like I'm holding back sometimes.

That reminds me: When we first really spoke to each other, at SPX this fall, we talked quite a bit about how you self-published The Blonde Woman with the aid of one of the final Xeric grants. I was struck by your passion for doing it that way -- there was an element of "if you want something done right, do it yourself" to how you described it. Is that a fair assessment? Did publishing that book in that way change the way you thought about the cost of working and publishing?

I don't suppose many artists would, but I think if I had ample enough sums to invest in myself I would maybe self-publish most of my work. I like having control. I like understanding what happens on the other side of the art. Even with things like anthologies, really, you don't know the quality at which they'll be printed or how they'll be designed or who else is in it. I'm such a print/design junkie that sometimes it's just disappointing to see opportunities for beautiful books missed or poor publishing choices made. Maybe if I was really starting to make some money, I'd be less concerned with the little things, but at this stage, I still feel lucky to have anything printed, so I want to maximize that.

I'll admit I was a bit of a nervous wreck through the process of printing The Blonde Woman, but that mostly had to do with just moving to NYC and losing a lot of my financial security, as I had to invest extra into the book after the Xeric. I did learn that basically, had it not been for the grant, I would have made approximately zero profit on such an endeavor. I can't even imagine wanting to be a publisher and putting that much effort into work that's not your own. It's truly altruistic and something I greatly admire.

In re-reading The Whale for this interview I was struck by how full it seemed compared to your more recent stuff. Which is an odd thing to say given how restrained it is in terms of tone and pencil line and "volume," for lack of a better word. But back when it came out I praised it for how immersive it was, how the way you sketched out environments made them seem like inhabitable three-dimensional parts of a world. That's not part of your work since then, it seems to me.

My most recent zine, Red Sands, is much in the style of The Whale, or at least the closest I've done in a while. Pretty heavy pencil rendering, inner monologue, sparse environment ... I've done so so much work in the past couple years between zines, anthologies, and books that I feel like I'm at a point where I can look at it all and really pick out the things that work and how they work and put them to better use. My style is always adapting and gaining. So even in this new zine, even though it's reminiscent of The Whale, all the sequencing in it is applied more intentionally.

Red Sands feels like much more of a story than anything else I've seen from you. It's a downright genre yarn, even. Is that a kind of comic you'd been attracted to doing before? Why now?

Actually I don't particularly like Red Sands ... I like the drawing, and I like the sequences generally, but I actually hate how much of a story it is! I had agreed to produce a zine as part of the residency I was at, and was really down on ideas with a little too much pressure on me. It seemed like an easy out! We only made 50 copies. I loved the residency, so I'm disappointed the art making part of it wasn't as rewarding. Really, I want to make more comics like Q. That's probably my favorite.

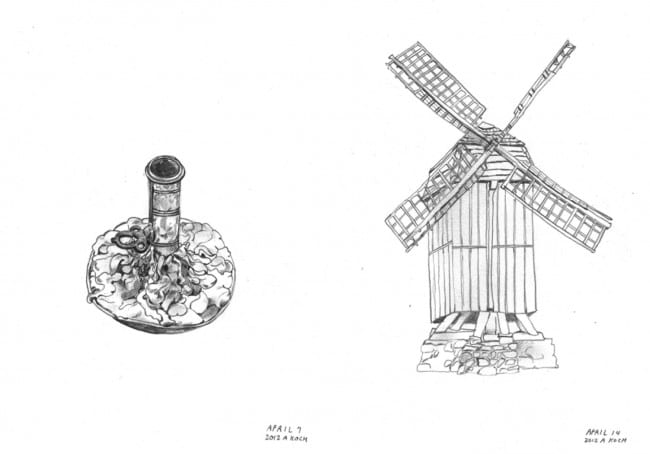

Field Studies, your new book from Floating World, is kinda funny, in that it's basically a sketchbook, containing life drawings you did while traveling, but the "sketches" are more solid and detailed than many of the drawings in your full-fledged comics, or at least the comics that aren't The Whale and Red Sands. It's a striking reversal.

It's part of my other art-life I guess, though not too distant. I am almost always deep into projects on the side from comics. It keeps me clearheaded to flex other skills. It also keeps me in touch with where I really come from, which is a fine art background. I specifically started the Field Studies project as a way to create a little income during my traveling. Something immediate and simple. It worked as a way to document what I was going through, too, and share it as I moved around, especially since I didn't even have a digital camera. But I had a scanner! Looking back through it now, it's meant a lot to me, in that I spent probably 20 minutes to an hour on each one, really studying and learning an object or scene. It helped tie me into my experiences in a different way than just loose sketches or photos.

It sounds like you see traveling as more of an end in itself than just a vacation. What do you get out of it?

When I decided to move away from Portland, I basically knew I didn't want to go back, but I didn't know where to actually go, so I've gone wherever I can think of. It's not a vacation because I don't exactly have a home or stability to go back to, it's just life. I've been an active traveler since I was a teen and pretty quickly realized I make a bad tourist. I like taking on new lives, experiencing places on a deeper level of community or experience. Most of the places I've been going, I know people there or have some art connection. It's amazing to build that kind of network and connect to the world that way.

Talk to me a bit about your relationship with Blaise Larmee and his (short-lived?) publishing imprint Gaze Books. The Whale is the only actual book he published, and nearly everything about it complemented his own book-length work Young Lions. Was that coincidence, or did your publishing relationship with him shape that book?

It was mostly serendipitous. I had finished The Whale in March 2010 about a month before the release of Young Lions. I was waiting to hear back about a Xeric for it and was trying to approach some possible publishers. When it turned out I didn't get the grant, Blaise knew I had been working on something and offered up a deal. We were both living in Portland at the time, so it felt pretty casual and natural. I like that I am associated with that venture in that way. The only book...that's not to say there won't be another book in five years...

What is it about your work that attracts cartoonist-slash-critics, or vice versa? You've published webcomics through cartoonist Zack Soto's Study Group, which has a critical/journalism component in its print incarnation. You publish strips at Comics Workbook, the group Tumblr run by one of the most well-known cartoonist/critic hyphenates, Frank Santoro. Blaise was maybe even better known as a provocative critic at Comets Comets at first than he was as a cartoonist in his own right, and you published with him. Even aside from where you've hung your hat for putting your work out, I think possibly your biggest critical champion has been Matt Seneca, who's been making a lot of comics himself. Are you a critic-cartoonist's cartoonist? Is that safe to say?

Well, it's funny because yes, within the comics community, I find my audience is definitely more for the critic/theorist type, but outside of that community its much more of a general young, art school type. I think people who have been more exposed to art books and conceptual approaches aren't quite as daunted by my work. I mean, I think people involved in comics just expect something much more specific than what I produce. It's been amazing though to be associated with people like Frank and Matt and Blaise. They keep me excited about being part of the community, even when I'm feeling like an outsider. I love talking and thinking about comics as a progressive format.

And oh, I forgot critic/comics-maker Derik Badman's reviews of your work, too! As a matter of fact, you're one of the very few cartoonists your age or younger who've gotten any traction in the existing sphere of comics crit, it seems to me. Sometimes I worry that there's a whole generation of art comics makers coming up through the ranks with no critical interlocutors, which probably isn't so healthy for them and definitely isn't so healthy for us critics. Do you see it this way from where you're sitting?

As in you don't think critics are discussing their work?

Right. I know I'm not, or not enough anyway.

Maybe that's true ... It's been four years since my first real mini, Warmer, came out. When it did, I mailed it to every critic contact I could scrounge up. I didn't actually know what to expect, just that it seemed like what I was supposed to do. It hasn't been that long, but still, there has been a significant shift to the internet for emerging artists in these four years. I think people are still wrapping their minds around how to approach work in this context. Do we take it as finished pieces? or just doodles? experiments? I was kind of surprised people started critically discussing The Blonde Woman as I was releasing it on Study Group. I hadn't actually even finished it, so realizing that it was fair game for discussion was kind of intimidating.