1. Title

1. Title

Bechdel’s title alludes to a famous children’s picture book, P. D. Eastman’s Are You My Mother?

In it, a young bird searches for his mother, asking the title question of a number of animals and machines, until he and his mother finally reunite in their nest. It’s ironic (and not ironic) that the hyper-intellectual Bechdel identifies her quest with that of a deprived infant. In figuring herself as a child, she highlights her continued dependence on her mother, reminding us that, even when adults, we’re still our parents' children. Are You My Mother?’s real central question might be “Why am I the way I am and what could my mother have done to make me different, i.e., a happier and more well-adjusted person?” Eastman’s hatchling asks a profound and crucial question — one that can be easily answered, and is. What makes Bechdel’s text so compelling, and at times frustrating, is that she asks questions about herself that cannot be fully answered, yet seems to believe that definitive solutions are available, perhaps in the writings of Donald Winnicott or Virginia Woolf, or in psychotherapy. The book documents a cartoonist’s struggle to banish doubt and uncertainty, hoping that an authority can deliver her from herself and from a life that comes with missing information. When Bechdel poses the question “Are you my mother? she seems to be saying, “Since you are my mother, you are my creator and therefore have authority over me. Give me the magical words or perform the soothing actions that will make me whole.” Like Eastman’s child’s picture book, Bechdel’s adult graphic novel hinges on the primal human struggle with interdependency and the psychic distress it inevitably breeds.

2. Subtitle

Bechdel subtitled Fun Home (her previous graphic novel) “A Family Tragicomic.” Are You My Mother?’s subtitle, “A Comic Drama,” echoes this phrase. Both genre terms (comedy and drama) are curious words to preface this book with. Though it includes a few lightly comic scenes, Are You My Mother? is relentlessly serious. Its non-linear structure often moves rapidly between scenes, excerpts from other writers, and personal archival materials —usually without identifying the chronology. This method intentionally empties the book of conventional drama, either heightened emotions or narrative suspense. For me, Bechdel’s internal drama was reproduced, not within the book, but internally; I was so frustrated with the choices she was making — especially her disabling self-criticism — that I became physically tense while reading. I really wanted to talk to her and discuss the problems with her thinking (as I understand them . . .) It was one of the odder reading experiences I have had.

Why, I wondered, is she so mean to herself, and why does she seem to celebrate intense self-criticism, which is really just an intellectual justification of self-loathing? (“Brutal honesty” is always brutal, but never honest.) Are You My Mother? is about the voodoo that the compulsively analytical intellect works on itself. Every parallel/coincidence in her life (and in her mother’s, and in Virginia Woolf’s, and in Donald Winnicott’s . . .) is never just a coincidence; it’s a sign of universal order that simultaneously excites, reassures, and oppresses Bechdel. The book appears to defend thinking about experience in this near-paranoid and critical (as in negative and judgmental) way as axiomatically Good.

3. Genre

Are You My Mother? has been called a memoir, a story about her mother, a recounting of Bechdel’s journey in psychoanalysis. None of these seem quite correct, or even helpful. More than any other graphic novel I’ve read, the book records the process of its own organization; it’s a “metabook,” as Bechdel’s mother calls it. It’s all about patterns, correspondences, similarities that Bechdel obsessively organizes into an archive of (hopefully) meaningful experience (with more telling than showing). Just as “comic drama” seems like intentional misdirection on the author’s part, so too does memoir misrepresent the book’s achievement; it’s as far away from, say, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, as an autobiography could be. (Can you really call something a memoir if it’s fundamentally opposed to chronology?) Are You My Mother? is a material graphic archive, with transcriptions of personal experiences, psychoanalytical reflections, recounted memories of other people, along with excerpts from letters, journals, newspapers, and the writings of Winnicott, Woolf, Adrienne Rich, and others, all rigorously interpolated and neatly organized. It treats life as a kind of research project that, to validate itself, must be perfected, visually and structurally. It’s a fascinating look into a cartoonist’s thought process and a book’s difficult creation.

(Its archival nature is even visible in some of the drawings, which, because they are recognizable as photo-referenced, include traces of what they reference: a collection of photos.)

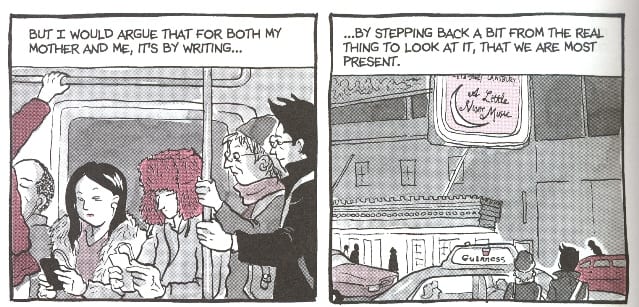

Ostensibly, autobiography is a record of life once removed from life itself: objective experience is filtered through the writer’s subjectivity. In Are You My Mother?, Bechdel’s mediates her experiences through other texts, interpreting nearly every moment (or so it seems) through the lenses of literature or psychoanalytic theory, rather than through direct personal reflection. In this way, the book is two steps away from “the thing itself.” It’s a process memoir, both for Fun Home and Are You My Mother?

4. Literary Modernism

In “The Waste Land,” T. S. Eliot mines literary tradition for scraps that he and friend/editor Ezra Pound) assembled into a non-linear, non-narrative epic poem. As carefully constructed as “The Waste Land” is, its power comes in large part from its polyphonic chaos; it’s a scrap heap of High and Low Brow culture’s Greatest Hits (from Dante’s Inferno to louts talking crassly in a bar). The reader is left to tease out potential meanings and connections between the dozens of scenes that make up this self-help, socially-redemptive cacophonous archive of rewritten and recontextualized fragments. Like Fun Home, Are You My Mother? employs a version of what Eliot calls the “mythic method” in his essay on James Joyce titled “Ulysses, Order, and Myth”:

“In manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity, Mr. Joyce is pursuing a method which others must pursue after him. They will not be imitators, any more than the scientist who uses the discoveries of an Einstein in pursuing his own, independent, further investigations. It is simply a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving shape and significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history. . . . Psychology (such as it is, and whether our reaction to it be comic or serious), ethnology, and The Golden Bough have concurred to make possible what was impossible even a few years ago. Instead of narrative method, we may now use the mythic method. It is, I seriously believe, a step toward making the modern world possible for art.”

The mythic method is always a personal archive, and Bechdel -- who mentions Joyce often in Fun Home -- replaces antiquity with the histories of her mother, Winnicott, Woolf, and others. Eliot’s ideas about narrative and myth, psychology and anthropology, and comedy and seriousness are helpful when thinking about Bechdel’s comic. As an organizational principle, Frazier’s anthropological The Golden Bough is to “The Waste Land” what 20th century psychoanalytical theory, especially Object Relations Theory, is to Are You My Mother?

5. Free Association

It’s interesting that, given psychotherapy’s investment in free association (which Bechdel discusses in Are You My Mother?), the book’s structure fully rejects it. Unlike the correspondence-driven yet open-ended mythic method of The Wasteland or parts of graphic novels like Daniel Clowes’s Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, Are You My Mother? imposes a perfect, rational order on the world and, at every step, tells readers precisely the nature and significance of this order, in a “note that this fact is connected to that fact” kind of way (reminding me of Craig Thompson’s Habibi). At times, Bechdel resists giving readers a greater interpretive role: she wants to make the connections and then tell us what they mean, an approach perfectly consistent with the OCD that both of Bechdel's books chronicle.

Bechdel’s method deviates from the intuitive approach employed by cartoonist such as Clowes, Chris Ware, Lynda Barry, or Charles Burns, who allow aspects of their narratives to reveal themselves as they draw. (This is not a criticism of Bechdel, just an observation about methods.)

In the book, she expresses a desire that her drawings have greater spontaneity and looseness. But her greatest virtue here is an allegiance to restraint that crosses the border into willing self-repression (an ironic move in a book about psychoanalysis . . .). The book’s strength is its highly artificial and strict composition: a controlled philosophical exploration of analysis and meaning-making masquerading as a comic-book memoir. Even Bechdel’s drawn facial expressions show a premeditated unnaturalness: At a key moment, it appears as if she acted out expressions in the mirror and drew what she saw, rather than tried to capture them from memory.

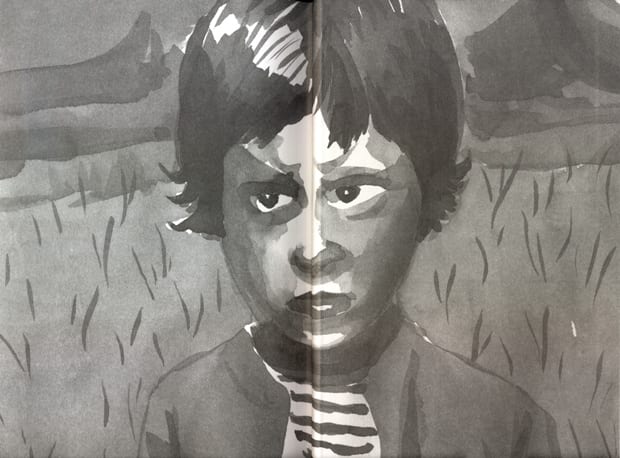

For a book about remembering, it oddly rejects the sloppiness and inaccuracy of recollection. Instead, her strategies make for a strange and other-worldly crafted object. But in the loose watercolor of the end-papers, she reveals something that remains hidden in the book’s interior:

6. Ending

The yes that eventually resolves P. D. Eastman’s picture book never quite arrives in Bechdel’s visual archive. In the final pages, she discusses her immediate need for a conclusion and constructs a reconciliation with her mother — or more accurately, she cartoons a possible ceasefire between herself and the mental image of her mother that dominates her psyche. The final scene appears to be a moment of affirmation, the yes that brings closure to Eastman’s narrative. But as Bechdel says, this memory is semi-fictional; its dialogue is “invented wholesale.” Can we trust her? Are we given an ending that’s false to reality, but true to her inner life? Perhaps by acknowledging her own and her mother’s woundedness — without invoking a mediating authority (Winnicott, Woolf, etc.) who can interpret them for her — something has genuinely changed within her, giving the book the traditional happy ending of the comedy. Perhaps we, and Alison, get the kind of epiphany we expect. Regardless, Are You My Mother? is a fascinating document of a mind at war with itself, yet at ease with the archival possibilities of comic books.