From The Comics Journal #282 (April 2007)

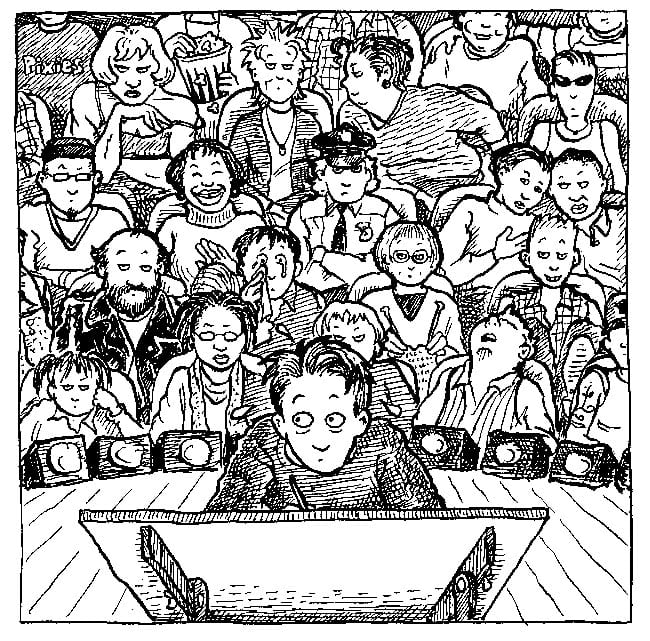

For readers unfamiliar with her work, it might appear that Alison Bechdel came out of nowhere to receive critical acclaim for her comic memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, published in 2006. But her devoted fans, who have been following her career for more than two decades, were well aware of her talent as both an artist and a writer. With its political commentary and spot-on observations of lesbian culture, her enduring bi-weekly strip, Dykes to Watch Out For, continues to thrive in print and online.

Bechdel took some time out of her busy schedule of writing, drawing and promoting her new book to talk about her work, her career and having her book banned in Missouri.

— Lynn Emmert

LYNN EMMERT: So far, your graphic novel Fun Home has been named “Book of the Year” by Time magazine, “#1 Non-fiction book” by Entertainment Weekly, one of the top 10 books of by the London Times and New York Times Magazine, and made the New York Times list of “100 Notable Books for 2006”: pretty heady stuff, there. Did you expect this kind of reaction to the book?

ALISON BECHDEL: No. [Emmert laughs.] Well, you know, I say no, and that’s true, but at the same time, I think, I don’t know. Somewhere deep down I knew that it was a good book, [laughs] like it should get attention. You know? So, while I am surprised, I’m also just really deeply gratified.

EMMERT: On your website, you talked about working on the “fringes of acceptability,” and now getting all this establishment recognition.

BECHDEL: Well, yeah. It’s been touch-and-go for me. I really didn’t know until now —January of 2007 — that I really probably am not going to have to get a day job. I’ve just been living with that possibility all these years and it’s been … scary!

EMMERT: Do you think the reading public is now more accepting of work that is outside of their comfort zone?

BECHDEL: I do. I think things have changed a lot in the 25 years since I started doing this.

EMMERT: How long have you been working on Fun Home?

BECHDEL: Fun Home took me seven years.

EMMERT: Wow. [Laughs.]

BECHDEL: Yeah.

EMMERT: I figured it was a pretty lengthy process, just because of the size of the book, but I had no idea.

BECHDEL: Well, I was having to do my comic strip concurrently, so that slowed me down, but I still feel like I needed that length of time just for it all to gestate properly.

EMMERT: So was it hard to work on that kind of project while doing your strip, all through that seven-year period?

BECHDEL: It was always difficult to grind to a halt. I alternated: I had two weeks on the memoir, two weeks on the comic strip, something like that. The transition days were very difficult, because I mostly just wanted to keep doing the memoir, but in the end, I think I would never have finished the memoir if I hadn’t had that constant prod of having to stop and start and switch gears. The memoir was so introspective and personal, it was really good for me to get out of my own ass [laughs], and think about the world and the stuff I write about in my comic strip, at regular intervals.

EMMERT: So that was sort of a break in between those periods of introspection. I could see how that would be helpful in some ways.

When you came up with the idea for Fun Home, did you approach your publisher, or did you produce the work and then shop it around? How did you get it published, ultimately?

BECHDEL: I had an agent, and at the point where I got the agent, I had some of the work done, but not very much at all, and it wasn’t really in any kind of coherent form. I had this really wonderful agent who worked with me to get the material in some kind of package so she could shop it around. What we did was, I finally came up with a synopsis of the book, when I was maybe halfway into that seven-year period. [Laughter.] I was able to do a chapter-by-chapter synopsis. On that basis, she was able to sell it.

EMMERT: For the benefit of the Journal readers that have not read Fun Home, can you describe what it’s about?

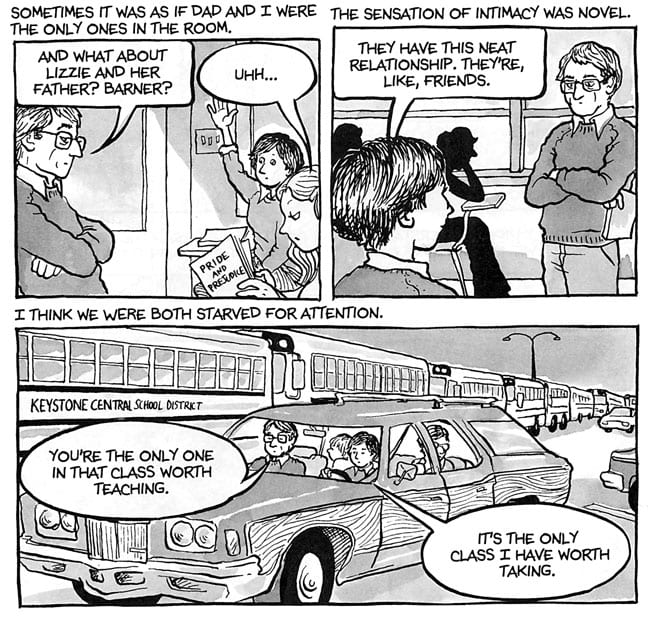

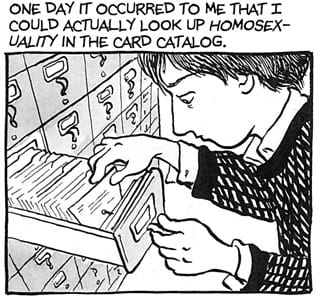

BECHDEL: It’s about my childhood growing up with my closeted gay (or possibly bisexual) dad. He was a high-school English teacher who was obsessed with interior design and spent all his free time restoring and redecorating our Gothic Revival house. He also worked as a funeral director at the family funeral home in the small Pennsylvania town where we lived.

EMMERT: What was your family’s reaction to the book? Did you let them preview it before you published it?

BECHDEL: Wait. Can I say one more thing about the synopsis? It was an illustrated synopsis, laid out like comic-book pages, because there’s just no way to —

EMMERT: Yeah. Well, with a graphic novel, yeah, that would be hard.

BECHDEL: So I didn’t have a whole lot of the drawing done, but enough to give a sense of what it would look like. OK, now my family. What did you ask?

EMMERT: Well, what was their reaction to the book? Did you let them preview it before you published it?

BECHDEL: Yes, I did. The big hurdle was my mother. [Pauses.] Early on, a couple of years in, I showed her a draft, and that was a very … I didn’t tell her until I’d been working on the book for a year, that I was thinking of doing this, because I didn’t want her reaction to inhibit me, I really felt like I needed to just work on it in that kind of —what am I trying to say? I wanted just some free space in which to think about it, to get a handle on the material myself. It was very difficult for me even to tell her I was doing it, and then to show her the stuff, and then to get her reaction. She never told me not to do it, but I knew that it was painful for her; it was always very upsetting when I’d get her reaction to whatever draft I sent. It was really quite emotionally tumultuous.

EMMERT: Did you do any editing based on your family’s reaction to parts of the book?

BECHDEL: Yes. I changed a few little things. There wasn’t much that they really asked me to change, but most of their requests I implemented. Some of them I didn’t, we sort of argued about those. I wanted them to know what I was doing all along, so I showed it to my brothers, I showed it to my mom. My brothers didn’t have as strong feelings about it as my mother, but it brought up a lot of stuff with them too. We all had very different experiences and stories about our relationships with my dad.

EMMERT: And your own points of view about it.

BECHDEL: Yeah.

EMMERT: The wave of autobiographical graphic novels in the ’80s and ’90s, it seems to me, was a bigger percentage of independent comics then than it is today. But it sounds to me like that didn’t matter to you, that this was something that you wanted to do, so that wasn’t really an issue for you.

BECHDEL: I always felt like there was something inherently autobiographical about cartooning, and that’s why there was so much of it. I still believe that. I haven’t exactly worked out my theory of why, but it does feel like it almost demands people to write autobiographies.

EMMERT: It’s interesting to me that it looks like all the members of your family had some sort of artistic talents. Is that true for your brothers — well, at least your parents. Is that true for your brothers, as well?

BECHDEL: Yeah. One brother is a musician, and my other brother, he’s sort of an outsider artist. He has great drawing skills, but he doesn’t really do anything with them; he puts all his energy into model cars and planes and things, which I guess is creative in a way, but I see that he can do beautiful drawings, but he doesn’t.

EMMERT: Doesn’t really do anything with them as far as art or getting them out there to the public.

BECHDEL: Yeah.

EMMERT: One of the themes in Fun Home I picked up on is of course the literature and reading and, in particular, I found that part when you talked about one of the times you felt closest to your father was when you took his English class. Does reading still play an important part of your life: Is that sort of a habit now?

BECHDEL: You know, I feel very bad about this, but I don’t read as much as I used to. And I’m not sure why. But I do think part of it is that the work that I do, you know, doing cartoons is very time-consuming. Especially when I was working on the Fun Home project, I really didn’t have time to read. I know that sounds crazy —

EMMERT: No, I understand.

BECHDEL: But I was working from the second I got up until the second I went to bed on that thing.

EMMERT: Wow. That’s a pretty rough taskmistress, there.

BECHDEL: I don’t know. I guess I am kind of a slow, methodical worker, but I don’t know how else you would do this stuff. You not only have to write it, you have to do all this painstaking drawing, and then you have to do design work, and it’s just all-consuming.

EMMERT: One of the parts, too, in Fun Home that I like is when you were taking your English courses and you resisted your instructor’s desire to interpret the books you were reading. How does that feel now, though, that readers and critics would be doing the same thing to your work?

BECHDEL: [Laughter.] That’s pretty funny. I was just thinking about that, how hard it was for me to understand symbolism and literary interpretation. I feel like it’s almost like a developmental stage, I think, that people need to go through. Like, 17 or 18, I just wasn’t there yet. I really didn’t understand how things could be about something other that what they appeared to be. But now I’m all about that, kind of: seeing behind the surface.

EMMERT: Certainly, a lot the things that are going on in your family are like that in the book. The surface lives people are living are very different than what’s going on behind that.

BECHDEL: Yeah. Yeah, but I didn’t know that then. And now I do. And now I look at the simplest [laughs] — I’ve just become very cynical and hyper-interpretive. Like, I don’t know, the other day, somebody told me to watch something online: It was this very moving story about a father with a paraplegic son and how the father does all these marathon races pushing the son in a wheelchair. And while it was very moving on the surface and this guy seems like such a great dad, [laughs] I just started coming up with all these twisted psychological motivations for how he was like actually — I don’t know.

EMMERT: Exploiting this situation? [Laughs.]

BECHDEL: Exploiting the kid, yeah. For his own personal gratification. Having this kind of critical perspective makes life very complicated.

EMMERT: In your book, you talk about your father going through therapy. If you’re willing to share that, is that something that you’ve done, and has that helped you, as far as —

BECHDEL: Oh my GOD, yeah —

EMMERT: — putting this book together?

BECHDEL: Yeah, I couldn’t have done the book without having done lots of therapy. I was very clear that I didn’t want the book to be about my therapy. I think that would have been really boring. But, it wasn’t just the emotional benefits I got from therapy, but a whole way of learning to think psychologically. Understanding what we were just talking about, these layers and layers of motivations behind people’s behaviors. Also, I think I even learned a psychoanalytic way of thinking: interpreting my life as if it were a dream. Even to the extent that dreams are a kind of visual language, and I don’t think I could have told this story without images. That was part of my syntax.

EMMERT: And then, did you feel like putting Fun Home together and getting it out there was part of that process, as far as working through your life and trying to get meaning out of it, and that producing this work was part of that?

BECHDEL: Yes. Totally.

EMMERT: It certainly was evocative for me. My life was very different than yours in some ways, but there were a lot of similarities too, and it made me really think about how one’s past shapes one as a person now, and how our relationships with our parents has a very lasting effect on our interactions with other people later in life. So, for me, it was just a really moving experience to read the book. It was one of those things: I bought it, and sat down and just read it all at once. I couldn’t put it down. I had to find out what happened. I really appreciated your willingness to be so out there about your family.

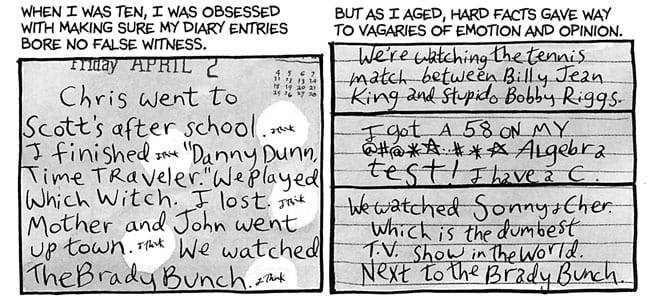

BECHDEL: Well, it’s almost a kind of compulsive behavior. I have this compulsive truth-telling syndrome. You know, there’s a chapter in the book about my obsessive-compulsive stage as a child, when I was terrified of lying. I feel like that’s really true of my life in general, growing up in a situation where there were so many secrets, I think I’ve swung maybe a little too far the other way. [Emmert laughs.]

It’s an incredibly revealing book, and I don’t know why I feel like I want everyone to know these intimate things about me. I know other writers who have told me they can’t imagine doing something that personal. It does feel a little crazy. I don’t quite understand it.

EMMERT: Well, I personally admire your courage for doing it.

BECHDEL: Well, but it’s not courage. I guess that’s what I’m trying to say. It’s insanity.

EMMERT: Not necessarily. I don’t think so. I saw it as a very positive thing — for me as a reader, anyway — and reacted to it that way.

BECHDEL: Good.

EMMERT: [Laughs.] I’m sure that’s why all the critics are raving as well, because there is just so much truth there, and that’s something I think, even in autobiographies, is quite frequently missing, that even people telling the stories of their lives don’t really tell it truthfully, in many cases.

BECHDEL: Well, mine’s full of lies, too.

EMMERT: Artistic license.

BECHDEL: Yeah. I think it’s important in any autobiographical effort to acknowledge the limitations of your methodology, of your ability to tell the truth, and I feel like I did do that in Fun Home.

EMMERT: So what was your reaction to Fun Home being banned in Marshall, Missouri, along with Craig Thompson’s Blankets? [Laughter.]

BECHDEL: My first reaction is: What a great honor! My second reaction is, it’s a very interesting situation, and it’s all about the power of images, which I think is something people need to talk about. I can understand why people wouldn’t want their children to accidentally think this was a funny comic book and pick it up and see pictures of people having sex. I can understand that. I think banning books is the wrong approach. If you don’t want your kids to read it, make sure they don’t get a hold of it. But I do understand that concern, because yeah, drawings are very seductive and attention-catching.

EMMERT: Do you think it had as much to do with the subject matter as it did with the fact that it was illustrated?

BECHDEL: Oh, I think it had everything to do with the fact that it was illustrated. I’m sure that library’s got all kinds of gay material in it. But if they’re just regular books with no cartoon illustrations, there’s not the same kind of concern about it.

EMMERT: I think that goes back to what you were saying about the power of images. I think one of the things, at least in the United States, that so-called graphic novelists have had to struggle with is the idea of the comic book versus the graphic novel, that comic books, in the U. S. anyway, have been so long identified as children’s reading material, or superheroes or things like that, that were pretty innocuous; but then when you combine that with adult themes and adult illustrations, that sort of presses a hot button for folks.

BECHDEL: Yes. I see this Missouri case as part of the whole evolution of the graphic-novel form. In that way, I’m very honored to be a part of the fracas, as the discussion evolves about what this form is.

EMMERT: I don’t know how much you know about European graphic novels, but it’s a very different sort of approach in terms of the culture. When I was in France one time, I was outside of what one would call a comics store, I guess, and people in business suits with their briefcases are walking in to buy their comics. And it’s just a whole different way of thinking about the medium.

BECHDEL: You know, I didn’t know much about the European comics scene until quite recently. I was just in France last fall, and got a glimpse of that and also saw this huge body of work that I had no idea existed. It was incredible stuff, a lot of which hasn’t been translated here. I’ve never seen it.

EMMERT: Right, yeah. One of the things that I will give kudos to Fantagraphics for is the fact that they are trying to bring some of that to the United States, like their translation of Epileptic and Lewis Trondheim’s work, because it’s just totally unknown here. Again, not work for children; it’s for adults.

So it’s something that I would personally like to see, and I think your book does a lot to change that perception.

BECHDEL: Yeah, that makes me happy too, when people just talk about it as a book, and not as a graphic novel. The fact that it was Times’ #1 book, that hasn’t even really quite sunk in, yet, that’s just really mind-boggling to me. It’s very similar for me to my struggles as a marginalized minority artist. I was just living for the day when I could be a cartoonist instead a lesbian cartoonist. That’s very similar to wanting my book to be seen as a book and not a graphic book.

EMMERT: That was one of the things that excited me too, that it was seen as a book, or that it was seen as a nonfiction book —

BECHDEL: Yeah, yeah!

EMMERT: Or that it wasn’t classified as one of the top 10 graphic novels of the year, that it was classified as what it is: literature.

BECHDEL: Yeah. It has made a couple top-10 graphic-novel lists, but I’m kind of dismissive. I know that’s really wrong. I mean, I’m very grateful to be on any top-10 lists, whatever the category, but I can’t help feeling like, “What do you mean? It’s a great book!”

EMMERT: Has the mainstream success of Fun Home been celebrated as a good thing in the gay and lesbian media? Has there been any criticism from the community?

BECHDEL: I haven’t heard any criticism. Mostly people seem really on board, you know? Really excited to see a subcultural artist who’s been kind of a community fixture for the past two decades cross over to a certain extent. I think the queer community has sort of taken it personally. People feel some ownership, like the book’s success is about them too. And of course it is.

EMMERT: Well, we’ll have to see what happens when all the comic awards come out this year, to see if you make any of those lists, the Harveys and the Eisners. [Laughs.]

BECHDEL: You know, I’ve never even understood those contests or entered any of them. That’s how out of the whole comics world I’ve been.

EMMERT: Well, you might end up in it, this year. ’Cause I would imagine it would be nominated for one of those.

BECHDEL: I haven’t even been to a big comics convention. This year I’m doing the trifecta: I’m going to Angoulême —

EMMERT: Oh wow!

BECHDEL: — San Diego, New York Comic Con, MoCCA.

EMMERT: I’ve only been to the San Diego Comic-Con and I don’t know how you can prepare anyone for that experience.

BECHDEL: I’m a little anxious about it.

EMMERT: It’s actually interesting, if you look at it as sort of social phenomenon. That’s how I do it. It’s easier to deal with than trying to take it all in, because it’s just kind of unbelievable.

I’m curious too, about the sale of your books. Obviously, with all the accolades that Fun Home is getting, has this helped increase the book’s sales, and has it also affected the sales of your other work?

BECHDEL: Well, it is having good sales. I just got a report, it’s like 40 or 45,000 copies, which, I don’t really even know what to make of that.

EMMERT: For a graphic novel, that’s really fantastic.

BECHDEL: When I’ve published Dykes collections, it would be great to sell 8 or 9,000 in the first year. So that’s my framework. So, this is just orders of magnitude beyond my experience. In terms of whether it’s affecting the sales of Dykes, I have no way of knowing that yet. I don’t think so, partly because many of them are difficult to get a hold of, many of the old books. But this is my great hope, that eventually the Fun Home frenzy will translate into more acceptance of the Dykes to Watch Out For books.

EMMERT: Were sales of the Dykes to Watch Out For collections mostly to gay/lesbian and women’s bookstores?

BECHDEL: Well, in the early days, they certainly were. But now there are only a handful of gay and women’s bookstores left. So … sometimes I can find Dykes to Watch Out For on the “gay and lesbian studies” or “gay fiction” shelf in a chain or independent bookstore. But not often. I don’t know where the bulk of them are sold nowadays. Maybe online?

EMMERT: How has being published by Houghton Mifflin, a big-name publisher, been different from your work with a small publisher in terms of editorial control and marketing?

BECHDEL: Light years different. I was a little anxious going in about what would happen editorially, whether people were going to try and make the book less … I don’t know. Queer. But that never, ever happened. My editor genuinely wanted this book to be itself, you know? And she really helped me to find its true shape. I’d never worked with an editor before, so that was a huge gift. And the marketing? Man, that was incredible. Partly, this was Houghton Mifflin’s first graphic novel, so I was the beneficiary of a lot of marketing and PR attention. I’d also been worried about getting lost at a big publisher, that I’d just be one of hundreds of authors, but that didn’t happen either. Working with small presses all those years, I worked with dedicated, talented people, but they had tremendously limited resources, and they were usually doing five or six jobs each. At Houghton, I had all these specialists — people focusing on the cover design, the bookstore displays, the media coverage. It was an unimaginable luxury.

(Continued)