Before the final leg of Anders Nilsen's Big Questions book tour had even started a parrot flew into his front room, wandered around for a bit, then died. Of all the windows in all the world that bird chose Nilsen’s, making for a poetic if grim end to a tour over a decade in the making. When I met Nilsen it was at the tail end of it and he was exhausted. “Drawn & Quarterly are really good – they support their artists when they tour,” he says in his slow skate-park drawl. “They wanted me to do maybe ten cities in America. But I’ve taken like 15 years to do this book so I just wanted to go to as many places as possible. I am only partially regretting this now.”

Before the final leg of Anders Nilsen's Big Questions book tour had even started a parrot flew into his front room, wandered around for a bit, then died. Of all the windows in all the world that bird chose Nilsen’s, making for a poetic if grim end to a tour over a decade in the making. When I met Nilsen it was at the tail end of it and he was exhausted. “Drawn & Quarterly are really good – they support their artists when they tour,” he says in his slow skate-park drawl. “They wanted me to do maybe ten cities in America. But I’ve taken like 15 years to do this book so I just wanted to go to as many places as possible. I am only partially regretting this now.”

The night I met him Nilsen had performed his slideshow talk in London’s Gosh! Comics in Soho, the talk he’s taken on the road for the last few months and given at places like Fantagraphics, The Beguiling, Quimby’s, as well as all over Europe and the entire length of England – he visited so many cities on his epic journey that you would have to go to some drastic lengths if you wanted to avoid him. Gosh! is essentially a well-lit glass box on Berwick Street: passers-by look in curiously as they shamble off to the pub, and we occasionally look out at them from our placid fishbowl. On the long central table made of ex-school desks from London’s East End, Nilsen set up his projector while people mused over the compass inscriptions of old students. Someone asked if he’d read Habibi yet, but despite he and Craig Thompson famously comparing the length and girth of their similarly weighty tomes, he hadn’t. And the reason? The tour, the suitcase. “It was either the projector or Habibi.”

I’d never been to a comic book reading before. I’ve been to countless readings by novelists and talks by comic book artists about their work, but I’d never actually sat there while pages were projected on a screen and the words in the bubbles read aloud. I was keen to see how the thing played out, or if it even worked. The whole thing came about originally when Joe Meno asked Nilsen and a couple of other artists who had illustrated his 826 benefit book Demons in the Spring to do a reading with him. The idea grew from there, and for his own tour Nilsen chose a couple of sections from Big Questions (Algernon and the snake, Bayle and the idiot) flashing single panels on the wall rather then entire pages. I found myself staring out the window in parts, looking up at the red-lit windows and watching the Soho prostitutes flick their cigarette ash on the men below, just listening to the thoughts of these little birds. It’s as if I was fine reading the book myself, and fine with the audio narration on its own, but together was too weird. Maybe it’s got something to do with that age-old problem where your Mum read you a bedtime story but she didn’t do the voices as well as Dad did.

What worked better were the pieces Nilsen had written just for the slideshow, short stories that have never appeared anywhere but his sketchbook, and whose images are simple black silhouettes with no lettered balloons to confuse the audio/visual experience. They’re stories about the Greek gods in modern times, maybe half a page to a whole page long: there’s Prometheus chained to a rock in the Middle East, with helicopters and explosions in the distance, and the eagle sent to devour his liver gives news coverage from below, telling him what mankind has done with his gift of fire. In another, it’s three thousand years after Poseidon chased Odysseus over the Mediterranean. Now he’s living in Wisconsin thinking about the old gods like you would half-remembered classmates from high school. Last he heard Bacchus owned a nightclub in Las Vegas, Venus is maybe somewhere in Hollywood, Eros runs something called the Internet. They’re funny. They even make Anders laugh when he’s reading them. It’s like they’re new and exciting and because of it they instantly have more life in them. I guess that’s why when I finally got around to emailing him some questions for The Comics Journal I open with something along the lines of 15 years?! How did you not go insane?! But I disguise it. Poorly.

CAMPBELL: What's your work routine like? Do you look for distractions -- like looking after an escapee parrot? I know lots of cartoonists who spend their days alone in a house and would go mad if it weren't for the animals asleep at their feet. Is that why Big Questions took so long to make? I'm not implying you're a waster, I just find it astounding that a creator can still have faith/interest in a project so long after its first appearance, when so much life stuff has happened between its start and end. I love hearing stories about scientists who devote their entire career to something unbelievably specific, like a certain kind of tree bark, because I just think Shit, you must have the hugest, unwavering amount of belief in this from the very beginning.

NILSEN: It's a little hard to remember my routine at the moment, having just spent most of the last two months on the road. But basically I think of making comics as a 40 (or 50 or 60) hour a week job. I get up in the morning linger a bit over breakfast, try to catch up on news and then get to work. I don't really think of the other stuff that occupies me as distraction for the most part, other than watching skateboard videos. If I suffer from distraction it's sometimes the less urgent parts of my work distracting from the more urgent parts. Or the easy parts, like answering email, distracting from the parts that demand more focus. Like drawing pages.

I never had much problem maintaining interest in the book. If anything I experienced a certain amount of impatience that it was taking so long, and that petty little things like having to make a living kept intruding. If it took a long time it's because...well, it's a six hundred page book, after all, and I have a hard time not getting excited about other projects just because I've got one that's a few years overdue. So the fact that I took time off to do five other books and a bunch of other short pieces in the meantime certainly didn't help. Other cartoonists I know have expressed reservations about starting longer projects because they worry that they would lose interest midway, or that their style would change. For whatever reason, every time I came back to BQ I found that I was still totally curious about the characters, and totally interested in what they would do next. Also, at the outset it was less like I intended to start a "long project" and more like I had happened upon these characters and the best I could tell from the story that was taking shape was that it would take a while to tell. Which ended up being a drastic underestimate.

There was also an element, every time I returned to it, of being eager to share it. Which sounds sort of silly, but it was really a bit like I had this glimpse into a little world – I had discovered this thing and I really really wanted to show my readers how cool it was. I'm sure it's like that for the tree bark scientists, too.

And as for my cat, she mostly sits in my lap, or walks around on my keyboard, rarely will she lay at my feet. But I know what you mean.

CAMPBELL: Before you started it, what sort of things were you into? Not just comics, but books or films. What other fictional worlds were taking up space in your head?

NILSEN: Right around the time that I first began thinking of doing a long form comic, and was beginning to flesh out the little birds I read several novels by the Norwegian writer Per Lagerkvist. He won the Nobel prize in the fifties at some point, I guess. But he wrote a few things, The Sybil, The Death of Ahasuerus, Barabbas, all dealing with man's relation to god and godlessness, playing around with biblical stories and Greek myths to make comments on modern life and questions. The novels have really wonderful, powerful imagery, and I actually thought at one point about just doing adaptations of them. A few years in I came across C.S. Lewis' Till We Have Faces, which is still one of my favorite novels. It's pretty dark. A retelling of the Cupid and Psyche myth, and seems much less sure of its worldview than his other writing.

CAMPBELL: So lots of stuff about the ('scuse me) big questions. I've never read that C.S. Lewis book. I should do – the Cupid/Psyche story is one of the oldest heartbreakers around. I always liked the bit about the ant taking pity in the temple and helping Psyche separate the grains. I actually wrote a review of The Game earlier this year and said something about it feeling mythic while belonging to no myth in particular. And your slideshow-only short stories are pretty myth-laden, with Poseidon, Aphrodite, Bacchus and that whole crowd. I don't really know what I'm getting at here apart from a far-from-astute "Man, you like myths, huh?" but there we go. Is it just Greek mythology so far?

NILSEN: Well, Greek and Christian. Playing with the Bible feels a bit different, of course, because people hold those stories a bit closer. To a lot of people they aren't just stories. You retell the Odyssey and you get points for referencing great literature, you play around with Jesus and people are likely to get offended. At least in theory. I've never gotten any hate mail. But that's part of what's interesting about it. They aren't just stories, they are the way real people have decided to understand the world. I've been meaning to re-acquaint myself with Norse mythology as well, but so far I haven't gotten around to it. And maybe now I need to let Marvel have its turn before I go playing around with Odin and Thor too much. Those ones are a little harder to use, too, because they are somewhat less well known. Less a part of the cultural foundations.

CAMPBELL: Obviously a lot of stuff can happen in 15 years, I think especially so when it starts when you're – what, 23ish? What was happening in your own life at each point you were doing the issues, and did that feed into their theme or philosophy?

NILSEN: I did the earliest bird strips when I was 22 or 23 and just finishing undergrad. By the time I put the first two issues together and began to think about expanding the story I'd been out of school for a while and was beginning to think about moving to Chicago for grad school. Right before I moved I went to Europe – Italy and Amsterdam, Spain and France to look at art, which was a pretty big revelation. Looking at all that stuff in real life is so completely different than sitting in a dimmed lecture hall looking at slides. I mainly was after the proto renaissance painters – I went to Padua to see Giotto's Arena Chapel, I went to Florence and saw Fra Angelico and Massacio's frescoes at San Marco. I took buses into these tiny little hill towns to see Piero Della Francesca's paintings. That stuff kind of blew my mind. It felt very close to what I was interested in in a number of ways. It's cartooning, really. It's no longer icons, but it's not yet realism. It all happened before people got all wrapped up in the humanistic technical details of anatomy and perspective and tricks with light and atmospherics. It's very straightforward, but still amazing and profound. It's still about the subject, about the story and about trying seriously to depict and grapple with what the artist feels is important in life. It's not about technique, and not about creating collectible objects for the wealthy. Which is, to a great extent, what painting became shortly thereafter.

CAMPBELL: I got the same kind of thing when I saw Hogarth paintings up close at the John Soane museum in London. There's so much cartoony stuff happening in the background that gets dimmed and fades away in reproductions. Did you make it to any galleries when you were in town?

NILSEN: Funny you should mention that. Tom [Gauld] actually took me to the John Soane to look at the Hogarths. And yeah, they were like the most elaborate political cartoons I've ever seen. Full of crazy symbols that you'd never guess, but also just nuts – like, pigs tied to people's heads and stuff. We also had about ten minutes at the...I think it was the British Museum. We looked at the prints and drawing collection, which we both geeked out on a bit, checking out the amazing cross hatching. Tom and I try to keep it real in the 21st century with the cross hatching, but its humbling to look at that stuff, for sure.

CAMPBELL: When you went back to edit the earlier pages, the sections farthest way from where you are now: were you dreading going back? Did you want to totally re-do anything? Not simply redraw a bird or two, but having visibly grown as an artist and a writer did anything (ideas, stories) just make you cringe?

NILSEN: Mostly not. It was clear from at least the halfway point that my evolution as an artist – me finding my way – was going to be part of what the book was, and I was fine with that. Still, I did want to make the book as cohesive and coherent as possible and I wanted to try to smooth some rough edges that seemed to be potential distractions, or just things that took me a while to settle on. So one thing I did was go back and make panel borders straight in places where they'd been a bit crooked or wonky. I also found that at least one plotline which is sort of important by the end, hadn't been treated as such when it first got going – basically Zwingly and Theodorus. So the two or three new scenes I added deal with that, for the most part. I didn't dread going back though, at first. I was happy to have the chance to make the book better. By the end of the editing process, though, I was kind of hating it. It was five months of 50, 60, 70 hour weeks of mostly little nit-picky revisions, and it was about the first time I kind of hated making comics.

CAMPBELL: Stuart Immonen said on Twitter the other day that drawing comics has a transformational effect on him – it makes him miserable and difficult to get along with.

NILSEN: Bummer. Yeah, I don't know Stuart, but that seems a prevalent vein of complaint in comics. If making comics sucked that bad for me I would stop and do something else. I mean, people are willing to pay me to draw pictures and tell stories. Yeah, it gets tiresome editing a 600 page book, but I kind of feel like I'm the luckiest person I know. It's super hard work, but in my experience so is anything else worth doing.

CAMPBELL: Just to go back to the slideshow thing for a bit. My friend Andy Riley did a series of cartoons called the Bunny Suicides which are totally silent things in which these mute rabbits kill themselves in the most insane and Rube Goldberg-esque ways. He's joked a few times about wanting to give a live reading of his cartoons because, well – how the hell would you do a live reading of that? When I heard you were doing readings of Big Questions I was wondering the same thing because there's no omnipresent narrator, there's no obvious role for you in the reading. Do you not like a narrator in comics?

NILSEN: I actually love narrators. It's not comics, but I remember when the Blade Runner "director's cut" came out when I was in college, and Ridley Scott had cut out the narration, I was kind of bummed. I liked the atmosphere it contributed, the sullenness of Harrison Ford's voice. I like the feeling that you have a companion guiding you through the story. And I really really loved Frank Miller and Alan Moore's use of narration in the '80s and '90s, like in Batman Year One, when you've got Bruce Wayne coming in to Gotham by plane, and regretting it, and Gordon coming in by train and regretting that...and their narration sort of goes back and forth in different script providing different perspective through the whole story. That stuff is brilliant. And I've definitely used it in The End and in Don't Go Where I Can't Follow. And actually even in Big Questions there are moments when Philo narrates the aftermath of the crash, and a few characters have little soliloquys. But in general I guess Big Questions just wasn't that kind of story. I kind of didn't want the reader to have a friendly companion guiding them. Ultimately I was interested in the reader just seeing what happens, and being given only clues to any character's interior thoughts and motivations, and sort of being left to figure it out themselves. Which is maybe something like what Ridley Scott would have said.

CAMPBELL: I like watching you mature though the book. Seeing your style progress so swiftly (it feels swift in a collection) makes it feel as if the story is growing and building up to something, as though we're getting more comfortable in the world as you do. Lewis Trondheim reckoned he wasn't much of an illustrator so he famously challenged himself to a 500-page epic (Lapinot et les Carottes de Patagonie) with the theory that after 500 pages of drawing he would have to pick up some skills along the way, which he clearly did. I know you had no intention of it being such a burglar-stunning epic, but do you think your style now would be very different if this particular book hadn't been there those 15 years?

NILSEN: It would be rougher, probably. I got much better, much faster because I had this endless book to always come back to, always the same characters and setting. I mean, I don't feel like I found a groove until maybe issue 8 or 9, and I was still refining my drawing – and making terrible pictures that had to get discarded while I was working on the last issue. I suppose that ones work grows and changes and refines continually, and I actually always have felt like if you're not a little uncomfortable with what you're doing, then the life is in danger of going out of the work. On the other hand, I think the style of the drawing is, and ought to be, dictated in some way by the subject and the story you're telling. So if I'd never done Big Questions at all, and instead had made Dogs and Water a 600-pager... nah never mind. That's too awful to think about.

CAMPBELL: At the back of the Big Questions brick you've got a cover gallery. What are your thoughts on each of the issues? Here's the first two. Would you ever go back to self-publishing?

NILSEN: I still self-publish now and then. I did The Game myself, and I did a mini with some postcards a couple of years ago. I occasionally have ideas for bookish work that doesn't really fit a workable or standard publisher format, and I'm perfectly happy to do it myself when that's the case. I'll probably do something like that with the silhouette pieces, too. As for more traditional comics, it's looking like if I want to serialize my next graphic novel, which I do, I think, I'll have to self publish it. Pamphlet comics just don't seem to be viable these days for smaller publishers. But it also seems like there are models out there now that might work. Last time I talked to Sammy [Harkham] he seemed pretty upbeat about self-publishing Crickets. And Charles Burns is just doing albums instead of pamphlets. So we'll see.

NILSEN: I still self-publish now and then. I did The Game myself, and I did a mini with some postcards a couple of years ago. I occasionally have ideas for bookish work that doesn't really fit a workable or standard publisher format, and I'm perfectly happy to do it myself when that's the case. I'll probably do something like that with the silhouette pieces, too. As for more traditional comics, it's looking like if I want to serialize my next graphic novel, which I do, I think, I'll have to self publish it. Pamphlet comics just don't seem to be viable these days for smaller publishers. But it also seems like there are models out there now that might work. Last time I talked to Sammy [Harkham] he seemed pretty upbeat about self-publishing Crickets. And Charles Burns is just doing albums instead of pamphlets. So we'll see.

CAMPBELL: With this issue you can almost hear the chain slip into gear. Were you always planning on introducing an element that was not birds?

NILSEN: I'd been doing the gag strips, and then began complicating them in the second issue, but I don't think it was until after that one came out that I started planning to add human characters. This issue was pretty huge for me. I hadn't tried to draw seriously for years and was mostly pretty happy that I seemed to be able to rise to the occasion. In fact I think some of the drawing in this issue is better than a lot of what I did in the next three issues. Beginning to really commit to doing comics for real, I kind of remember having a ball. It was all pure potential, I was a little drunk on the possibilities. The contrast, too, between how much fun I was having compared with how timid and unhappy most of the other students at the Art Institute seemed, was pretty stark.

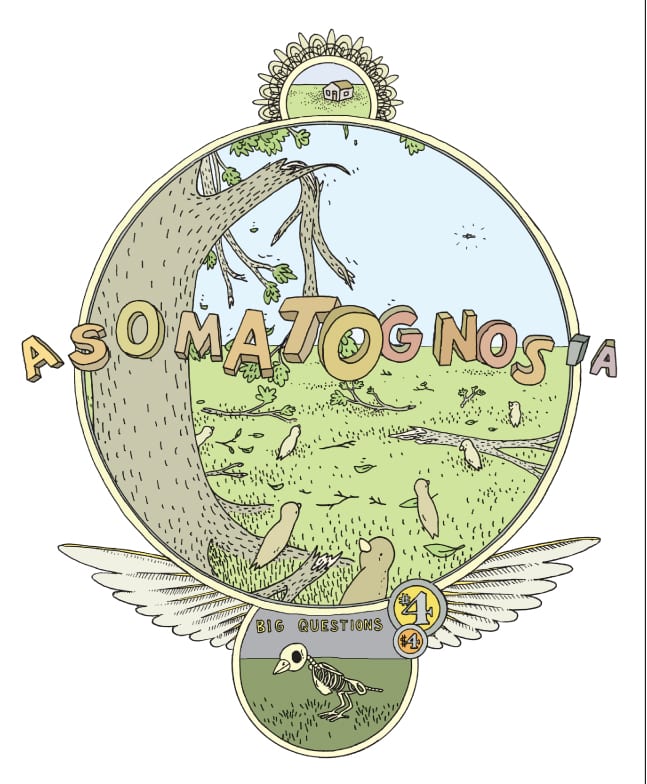

CAMPBELL: Asomatognosia… or "Words We Had To Look Up And Are Glad We Did"

NILSEN: Yeah, I had really decided I wasn't happy with the title "Big Questions" by this point, and one of the fun things about making little books is that you get to play with the idea of the title. I came across the word in an interview with Oliver Sacks and it seemed so full of weirdness and fascination, along with a lot of potential for symbolic resonance, I kind of had to use it. Plus it was just big and dramatic. I was also listening to lectures on existentialism at this point, and I know the idea for the Sisyphus story I did for Kramers Ergot #4 bubbled up around the same time as I was working on the drawings for the three visitors of Betty Sentry.

Two of my favorite pages in here are the squirrel's fight with Algernon, which also ends up being the most glaring blind alley in the book, since I completely lost interest in them later on.

NILSEN: I was pretty into the minimalism of the front cover – I'd been looking at a lot of nineteenth century graphic design and was kind of in love with some of the really simple elegant design I was finding, but I think I was a little worried that it was too quiet. It was almost monochrome. So I decided to put a back-up, more eye-popping alternative on the back. Trying to have my cake and eat it too, I suppose. The back cover is also the last time I used the motif of the block of colored cubes. My intention had been to have the configuration of cubes follow and echo the development of the plot, but after this point the plot got more complicated and the colored cubes just didn't seem that interesting any more.

NILSEN: The drawing in this issue, and in #5 before it is pretty rough, and, looking back, my least favorite stuff to look at. I feel like I lost my way a bit, wanting to recapture some of the spontaneity of the way the series had started, but not really knowing how to do that. Somewhere while working on these two issues I started the first Monologues book and that became an outlet for a more spontaneous way of working. Which allowed me to really get serious about drawing well in Big Questions. It's probably worth mentioning that a lot of numbers four five and six were drawn out of order. The plane crash in issue 6 was drawn, for example, long before Betty's conversations with her visitors in issue four. I was still figuring out how to write a story.

NILSEN: This issue is very much a dividing line for me. It's the first issue that Drawn and Quarterly published, for one thing. Cheryl, my girlfriend at the time, had printed the guts of #6 on a small offset press in our garage. The plan was for her to continue doing so, and for me to self-publish the rest of the series. But she got sick that year, and that plan became impossible. I'd gotten small grants from the city of Chicago to help with printing costs for #s 4, 5, and 6 and wasn't eligible any more, so it felt like getting a publisher was basically a necessity. But it was a dividing line also in that it's the issue where I'd finally decided how I wanted to draw. I also feel like it's where I emerge finally from the kind of naive jumble of just adding problems and characters into this world I'd created and I begin having to grapple with them and actually see how, and if, they all work together.

CAMPBELL: This cover (and the next few) is properly anatomical. There's a museum here in London called the Grant. It's mostly the collection that used to belong to Charles Darwin's tutor (though it's been added to over the years). There's an old woman called Janet who just sits there all day producing these amazing pencil, ink, or watercolour paintings of different specimens that take her fancy. She's pretty much got free reign of the place and gets monkey skeletons out of the old Victorian cupboards all on her own. I once saw her painstakingly inking the constituent parts of an elephant heart. Were you drawing from life too?

NILSEN: No, I was looking at old botanical illustrations actually. The actual bird anatomy was adapted from an intelligent design website. It's definitely my favorite cover of the series. I actually considered using it for the cover of the collection, even.

CAMPBELL: This story about Algernon searching for Thelma is heartwrenching.

NILSEN: Yeah. #9 was the first time I came back to Big Questions after Cheryl's death, and there was definitely something strange about drawing that sequence, which was basically what I was going through, though I'd written it long before she even got sick. I also feel like #9 is the point where my drawing and layout gets consistent, where the drawings I actually like don't feel like flukes any more.

NILSEN: This is a cover that still looks so much better in my head than it does on paper. Like several of the other ones. It probably could have used a few revisions. I still like it though. A frozen, iconic fight scene. Makes a nice tattoo, too.

NILSEN: By this point I was working from an actual script, and yet, the story was still expanding and fleshing itself out. In editing it for the collection it's these few issues that take place at night that required the most re-arranging. Morning comes in #11, and #12 happens entirely in daylight, but I got a late breaking idea about giving some small hint of backstory to the Pilot, and having one of the birds enter the cockpit of the plane, and so I lead #13 off with another nighttime scene. All that had to be rearranged for the collection. Also I used a few different strategies for panel design for the nighttime scenes, trying to come up with a workable equivalent to the panel-lessness I used in a lot of the daytime scenes. Correcting that to make things consistent was a chore.

NILSEN: This is one of my favorite issues. It's very self contained, and really almost irrelevant to the overall story. After a short dialogue with Betty and Clay at the beginning it's mostly just a long extended fight scene with the crows. I was channelling my Marvel here, for sure. Enjoying the balletics, and tension and humor of the melee.

NILSEN: Very little really happens in this one. Certain things had to take place to set the stage for the denoument that happens in 14 and 15. Optimistically, it functions as the calm before the storm, but I have a feeling that a lot of people probably picked it up and thought, "Oh brother will this thing never end?" Still, I kind of love the little conversation between Theodorus and Eusippius while they wait for the Pilot to show up at the river.

NILSEN: Everything comes to a head here. It was tremendously satisfying to finally get to this point in the story. I remember, too, having to take a few minutes to sort of mentally check myself (spoiler alert?). Was I really going to kill off one of my favorite characters? Okay, yeah. Has to happen. All right, here we go. Several get the axe here, but one in particular gave me pause.

NILSEN: I really loved drawing the contours of the caves in this one; though it's also true that the scenes with the Pilot underground gave me the most trouble with both drawing and plotting that I'd had in a long time. There are several pages from the sequence that I cut entirely. I also went back and forth about whether the dialogue between the Swans should be legible to the reader, finally deciding to leave it out except while they're underground. But it took some willpower to take an entire dialogue, which I was actually pretty happy with, and then decide to cut it because it was just necessary that the swans remain out of the readers purview. The decision to end the story the way it began, with a simple comic dialogue between two birds also came late, but now seems obvious. There's a way in which those little dialogues will always be the most important part of the story to me.