A Not-So-Secret History of Superman, Wonder Woman, and the American Superhero.

1. Superheroes Selling

Three recent DC comics Dark Nights: Metal #1, Batman: The Red Death #1, and Batman: The Dawnbreaker #1 include an advertisement for Snickers bars. A reader could be forgiven for momentarily thinking that the ad, which looks a lot like the narratives it accompanies, is part of the story:

As super-villain Gorilla Grodd attacks the stadium, he proclaims that “Events mean nothing to [me]!” But, as Superman discerns, this gorilla’s not what he seems: he’s “just a hungry fan.” After a few bites the Snickers works its magic, soothing the “crabby” fan’s rage.

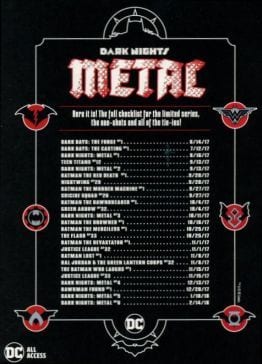

It’s odd to see an ad with an event-hating fan in these particular comics, all of which are part of what the industry calls a Crossover Event. To follow an event’s sprawling narrative, fans need to buy a lot of comic books released over several months. While “events mean nothing” to villains (and crabby fans who refuse to buy the required books), they mean a lot to companies and their bottom line. Each of the twenty-five comics/chapters in DC’s current event Dark Nights: Metal costs $3.99 or $4.99. In the past, a major crossover from the “Big Two” (i.e., DC and Marvel) occurred every few years. Now they pop up once a season. We’re living in the pricey moment of Perpetual Event.

The candy-bar ad’s “event” reference must surely be intentional (at least I think it is). It’s some meta-fun for attentive fans who will get the joke: “Only cranky readers don’t like comic-book events!” Whether intentional or not, the joke fits perfectly within what we could call “The Crossover Event Worldview,” in which everything is meaningful because everything is meta. Event comics sell themselves as stories about stories, full of Easter eggs and allusions that reward true believers versed in the company’s vast comic-book continuity.

To drive sales numbers, events promise “earth-shattering revelations that will forever change the characters you love,” making it essential to buy every issue. Crossovers reorganize a company’s fictional universe, revise heroes’ and villains’ origin stories, introduce new titles, and meditate on the cultural and personal relevance of the kinds of heroic stories that mainstream fantasy comics traffic in. To both widen and close the loop of meta-circularity, current events typically evoke past ones: Dark Nights: Metal #1, for example, drops references to DC events such as “Final Crisis” and “52”:

In these ways, crossovers deliver what they promise — at least until all is undone by the next event, which is just on the horizon. At its core, each event comic book is like the Snickers comic: it’s an ad. Events market the company’s past, present, and future products.

The event’s self-referential obsessiveness may strengthen the bond between fan, character, and company, but it can be turned against the comics by readers tired of being sold the same thing over and over. Dark Nights: Metal #1, Batman: The Red Death #1, and Batman: The Dawnbreaker #1 all begin with the “stories about stories” motif:

It takes a self-assured writer to draw attention to the possibility he’s retelling the same old super-fable. After reading the first few pages, many readers must have said, “Please stop. I've heard this one.” The tale offered by Dark Nights: Metal has been told hundreds of times, both in crossover events and in non-event comics: a cosmic foe threatens the multiverse, dozens of heroes must unite to defeat it, the battle takes a profound toll on everyone, some heroes temporarily become villains, others temporarily become dead, and a few bad jokes try to lighten the oppressive darkness.

And this event relentlessly markets itself as dark: it's called Dark Nights, it's set in a “Dark Multiverse,” the stories involve “dark matter,” the word “dark” appears every few pages. This obsession even works on a meta-level by tying this event to our current comics era, which is often called “The Dark Age.” All these choices represent “brand identity” run amok. Perhaps it’s executed in this blunt way to ensure that readers can't miss the sales-pitch.

Since the early 1990s, fans have been complaining. They regularly criticize Marvel's and DC's comics as too dark, as favoring over-the-top violence instead of subtle characterization and well-crafted plots. In Batman: The Dawnbreaker a character says “Th-the darkness. . . It destroys everything,” a complaint easily lodged against the relentlessly grim comic it appears in:

But I'll give Dark Nights credit for “brand commitment”:

Like many comics in the event, Dawnbreaker is metaphorically dark in its content, and literally dark in its coloring:

As these event comics deconstruct themselves (are they daring us to mock them?), they draw attention to the fact that we just bought what might as well be a reprint from last year. (At my local shop on a recent “new comics Wednesday,” a fellow reader said to me, “I’m sick of these ‘grim and gritty’ cosmic comics!” — he no longer collects events.)

2. Selling Superheroes

For many readers and the comics’ creators, though, the meta-narrative driving each crossover event is a high-minded endeavor that plays into one of our most cherished cultural and comic-book memes: “We are the stories we tell.” And events, with their mass gatherings of heroes and villains, tell a grandiose story about our moral striving. In a Superman comic from a few years ago, the narrator extols the hero as the “embodiment of the very best in us. Our inspiration to . . . aim higher. Each and every one of us is . . . Superman.” This transcendent belief grows out of the hallowed American comic-book traditions of self-promotion and self-aggrandizement, of seeing superheroes not as corporate properties but as culturally natural and necessary aspirational figures who rise above the petty notions of product and property. In the 1960s Marvel’s Stan Lee proclaimed that super-characters serve the lofty role that gods of classical mythology served for ancient Greeks and Romans, a notion widely endorsed by comic-book readers, writers, and publishers ever since. (Promoting a Smithsonian online course, Lee and Batman Dark Knight Trilogy producer Michael Uslan tell us that “The . . . gods of . . . Greek and Roman myths still exist, but today . . . have superpowers.”) It’s nice to think that Flash and Wonder Woman emerged from the collective unconscious in order to help us become who we really are. While the mythic view keeps everything meta and meaningful, it obscures an important reality: actual people laboring under work-for-hire contracts (or no contracts) created these characters, and the companies who own them have often denied creators royalties or a fair share of the profits.

Like these companies, we fans have a deep need to own other’s imaginative property. A meme that recently made its way around Twitter represents the perfect expression of this covetousness (so much so you might think it’s a parody):

Importantly, this idea isn’t the sole province of the rabid fan, the kind to whom crossover events mean everything. I once heard a scholar tell an enthusiastic audience of comic-book readers and academics that superheroes are genuinely mythic, a part of our shared cultural inheritance and therefore ours to do with as we wish. I knew that if I tried to make and sell my own Flash comic book, expensive lawyers would quickly tell me I shouldn’t believe everything I hear.

3. Selling is Canon

This brings us back to Snickers. How can we square the American caped crusader’s cultural relevance and noble mission with a role the character has played since its debut: corporate shill? Though many heroes’ alter egos have been mild-mannered types like Clark Kent or Peter Parker, another identity — not a secret identity but a very public one — has badgered us for decades: a confident, unapologetically crass character we could call “The Pitchman”:

The hero-meets-product alliance represents the most important corporate crossover event: the ongoing merging of our escapist fantasies and capitalism’s desires. It’s a perfect world, this corporate superhero universe: publishers and creators sell the value of superheroes who sell candy in an ad about events that appears in an event comic that sells other comics/other events that sell the value of superheroes and their (i.e., our) stories. The circle is unbroken.

If it seems jarring that the super-being who’s trying to save the world and uphold what’s best in us is also hawking candy, comic books, and amusement park rides, it shouldn’t.

More than truth and justice, commerce is the American way boldly personified in these heroes. Superman and his super-ilk may look like examples of what we call, somewhat pretentiously, a “literary character,” but they’re not. They’re a special kind of commercial fiction: the “corporate character.” To best serve those who have trademarked them, they live an existence so unstable and tenuous that, in reality, there is no Superman, only thousands of versions of “Superman.” Corporate characters are by definition amorphous, loosely defined by a name, logo, and a few back-story facts. In movies and countless comic books, however, even these ostensibly “essential” elements are repeatedly up for grabs. Whenever sales flag, the character morphs. Spider-Man is a white male, then he’s not. His costume is red and blue, then it’s not. His name is Spider-Man, then it’s not. He’s dead, then he’s not. Etc., etc… With every new artist, writer, editor, crossover event, or product endorsement deal, the character undergoes yet another metamorphosis. Superheroes, then, are meta-characters; one moment they’re flying around a fictional universe beating up villains, and the next they’re breaking the fourth wall selling us toothpaste, underwear, and fruit pies.

In each of its guises, the super-being enacts its owner’s will. This holds true for 2017’s most beloved character, Wonder Woman. (They're even calling 2017 “The Year of Wonder Woman”). She’s rightly celebrated as a feminist icon, but her history is more complicated, less uplifting. She’s long been a saleswoman happy to hype what she’s ordered to:

Since an eager submission to authority is not the most feminist of traits, we “forget” her crass commercial superpower. It really kills the fantasy.

**

Expressing a level of fan outrage that even a crate of Snickers couldn’t cure, MRA social-media warriors believe the comics industry ruins “our beloved characters” by changing their race, gender, or religion. But they should remember that these “icons” have long histories as elastic properties equally adept at saving the universe and peddling Twinkies. Such fans might feel less horror if they recalled that Thor™, Spider-Man™, and the rest have always crossed over, changing whenever the boss thinks it necessary, licensed out to anyone who’s got enough cash. Whether we like the changes or not, “our beloved characters” have never been ours.

In recent weeks, this alliance has taken a new, and disturbing, turn. Marvel teamed-up with Northrup Grumman, one of the world's largest defense contractors, creating a perhaps inevitable synergy between violent corporate heroes and violent corporations. It's eerie how easily super-beings cross over to the military-industrial complex:

If comic-book publishers believed that superheroes were contemporary gods, inspirational role models, or culturally relevant figures, would they pimp them out to Snickers and ballistic missiles? Probably not (and yet . . ). These alignments reveal the political relevance of superheroes in 2017. Despite their noble words, they're just another bunch of high-powered hypocrites out to make a buck.

So rather than see ads featuring super-beings as separate from comic-book events and continuity, we should embrace them as canon. A crucial part of American superhero history, they remind us that caped crusaders will forever do what they’ve always done: sell stuff.

_____________________________________________________________

PS: Here I write about a DC comic-book series I liked, Batman Unseen, which narrates a world outside of candy, crossovers, canon, and continuity.

Ken Parille is editor of The Daniel Clowes Reader: A Critical Edition of Ghost World and Other Stories. He teaches at East Carolina University and his writing has appeared in The Best American Comics Criticism, The Believer, Nathaniel Hawthorne Review, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, Children’s Literature, Comic Art, Boston Review, and elsewhere.