“I’m a terrible writer, is what it is,” Graham Chaffee tells me—but I don’t believe him. The cartoonist, who spends his days working as a tattoo artist in his Hollywood studio, is being too modest. His fourth graphic novel, To Have and To Hold, is a gut-punch thriller that argues otherwise, proving that Chaffee’s a storyteller who knows how to make the most of his medium. Whether he’s using spoken dialog or intimating a narrative through his character’s gestures, facial expressions, or body language, his work is consistently engrossing.

“I’m a terrible writer, is what it is,” Graham Chaffee tells me—but I don’t believe him. The cartoonist, who spends his days working as a tattoo artist in his Hollywood studio, is being too modest. His fourth graphic novel, To Have and To Hold, is a gut-punch thriller that argues otherwise, proving that Chaffee’s a storyteller who knows how to make the most of his medium. Whether he’s using spoken dialog or intimating a narrative through his character’s gestures, facial expressions, or body language, his work is consistently engrossing.

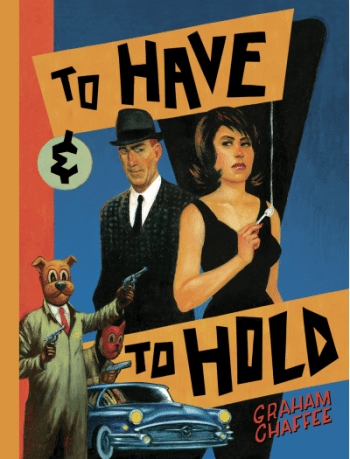

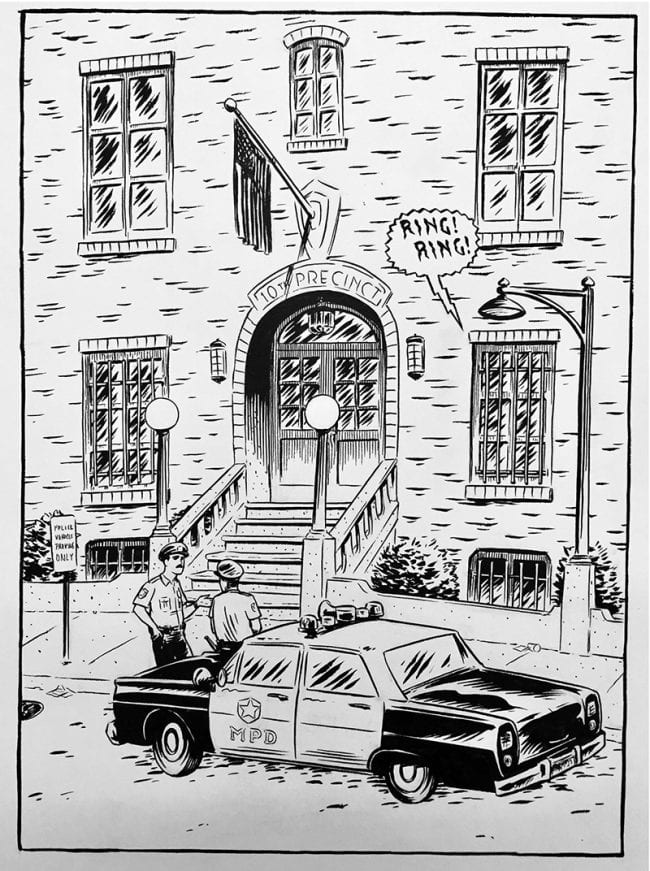

Set in the early 1960s at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, To Have and to Hold centers on Lonnie, a disgraced ex-cop forced to eke out a living as a night watchman, and his beleaguered wife Kate, whose marriage never served up any of the bliss promised by all those TV commercials and glossy magazine ads. Now the Ross’s life together is etched by petty bickering and smothering resentment. When Lonnie discovers that Kate has been stepping out on him, he reacts in a way that brings their world into chaos and threatens to destroy more than just their lives.

Over the course of 200 chiaroscuro pages, Chaffee puts his spin on the classic heist story through deeply-articulated characters and a black-and-white style perfectly matched to the subject matter. On the one hand, his work captures the visual élan and narrative smack of some of the best classic Hollywood B crime pictures—think 1950’s Armored Car Robbery or 1953’s Crime Wave, while on the other hand it recalls the melancholy bleakness and sophisticated relationship politics of noir writer David Goodis, rather than the cardboard rat-a-tat of Mickey Spillane.

Over the course of several emails, Chaffee and I discussed, among other things, his creative process, the influence of cinema on his work, and the dark side of the promise of prosperity in postwar America. -Mark Fertig

You’re a full-time tattoo artist in Los Angeles. I’m curious about how that job overlaps with your work as a cartoonist. Does your work in one area inform or influence your work in the other, and do you ever struggle to avoid burnout?

Tattooing is restrictive to my work as a comics artist. I am so used to crafting these clean designs with recognized protocols for outline, shading, and color, that it’s hard to switch gears and loosen up as a draughtsman. I fear my comics are more controlled and uptight than I’d like them to be. I’m no Ware or Burns, but I’d like to be even less so: looser, more expressive, more Julie Doucet!

You once described your graphic novels as “paper movies.” The narrative sensibilities in To Have and To Hold are often unmistakably cinematic—even the cover is reminiscent of a vintage movie poster. In what ways do films and filmmaking inform your process?

It’s more that I see the story like a movie in my head. I’m trying to draw the scenes the way I’d shoot them if I had a camera. I watch a lot of movies, but I don’t study specific scenes or shots or anything. This also means I don’t use a lot of narrative boxes or thought balloons—I’m a “show it, don’t say it” kind of guy. My characters run around and do stuff, and you gotta infer their motives and desires from their words and actions, because we’re not going inside their heads. This means a lot of the weight is carried by the actors—their gestures, body language, facial expressions, tone of voice and whatnot.

To Have and To Hold is a noir crime story in the classic sense. Does your fascination with noir come just from movies, or are there other sources—pulp fiction, true crime, or other comics and graphic novels?

Hmmm…Well, I read a ton of pulp fiction and detective stories. I love Cain and Thompson and Hammett and Chandler and all that crew—Christie, Sayers, Greene, Highsmith, Doyle—not to mention the Scandinavians...

But Noir seems more a product of postwar cinema—and I think my noirish influences are more movie-oriented than bookish. I’m never thinking about books or authors when I’m trying to write or draw a scene; I’m definitely moving a camera around in my head.

The Cold War, specifically the Cuban Missile Crisis, is a constant presence in the story. Why did you choose to situate the story in that specific moment in history?

To date, all my stories have taken place in the same imaginary east-coast metropolis and the time is vaguely 60s—that’s a paradigm that just sort of evolved through the various graphic novels. You’ll see the same people and buildings recur throughout my work.

Anyhow, for To Have and To Hold, I needed a realistic news broadcast that could play on the radio or television in various scenes. I found one from October of 1962 and the Missile Crisis was the main story—so I thought, okay: October ‘62—that’s when all this happens. As the plot developed, the Crisis seemed more and more appropriate as a paranoid backdrop for a story with so many tense and unhappy people. So, to be honest, it was a serendipitous sort of accident.

I couldn’t help but grin when I saw your nod to the poster for The French Connection. It’s just one of many cultural references that are peppered throughout To Have and To Hold. What’s behind them? Do you ever worry that they might yank your readers out of the story?

I’ve been pulling that shit since Big Wheels—I can’t help myself! Sometimes, I see an image that’s just too good not to include—too inspiring. Like this painting by Millard Sheets:

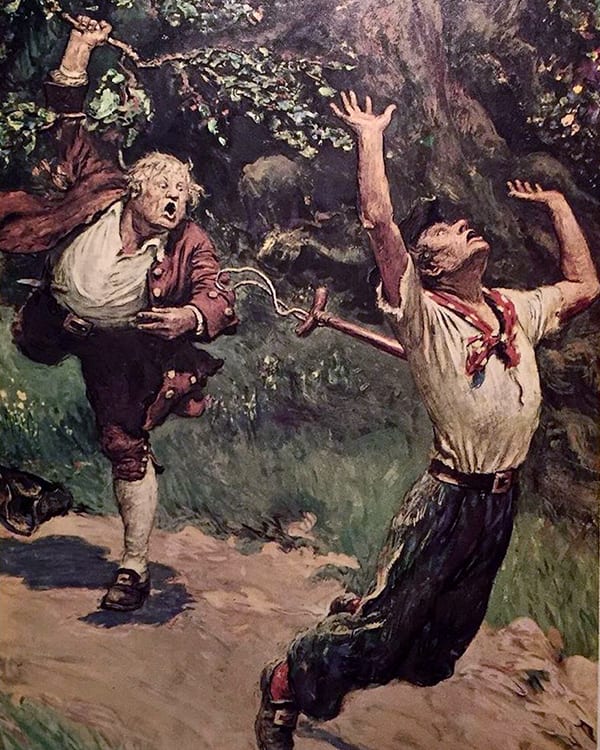

…or this one by Norman Price, from Treasure Island, which has haunted me since childhood—my French Connection image is my way of giving it a 60s update, while also paying homage to the Friedkin film.

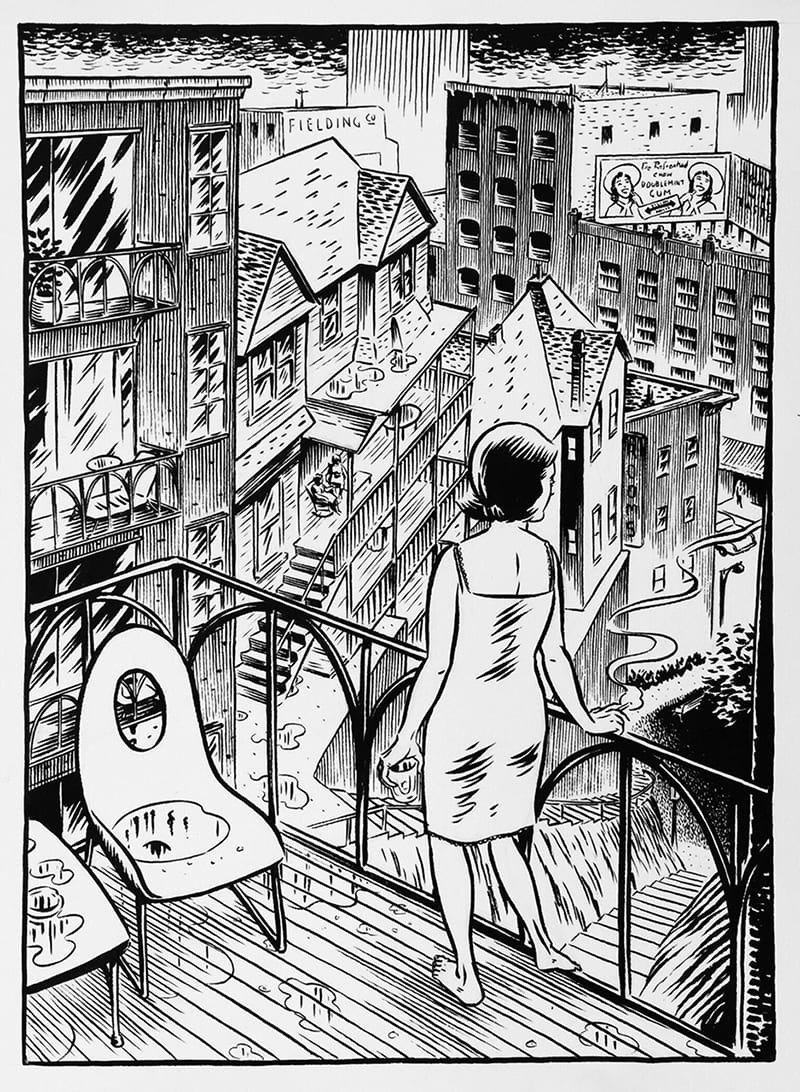

While we’re here, I’d like to point out the closing reference to the closing shot in Psycho:

So, yeah—it’s childish, but whatevs—I look at it this way: anyone who would get these references is likely the sort of person who would enjoy spotting them more than they mind being briefly taken out of the story...at least I hope so.

Your drawings capture the dark moodiness (or is it the moody darkness) that goes hand in hand with noir, while retaining a confident, economical quality that lends itself to this kind of storytelling. Is that something that comes naturally, or did you need to tweak your technique for this project?

It comes naturally. I have always wanted to tackle noir—love the dramatic imagery—my favorite panels are the nighttime shots. It’s a challenge to compose using only black and white. I have become reasonably adept at it, but I’m still far behind masters such as Alex Toth and/or [Epileptic author] David B. In fact, I have recently branched out into gray—which you’ll see in my next book.

Your action sequences are especially vivid, yet so much of the story is told through smaller, often silent panels that rely on facial expression or body language instead of dialog. I’d like to learn more about your process here. Do you work from a tight outline? Are there moments, for example, when you realize a page needs an additional panel, or that a panel is unnecessary?

Good Dog had a typed script, then a fully finished sketchbook layout with lights and darks, before I started the finish art. So I did the whole book three times, which was exhausting and slowed me down a lot. And then Gary [Fantagraphics publisher Groth] told me it was too short for a graphic novel and I had to go back through it and add 30 more pages somehow...

So for TH&TH, I decided to just get into finish art as soon as I could. I plotted the story—the main bits of it—and then wrote the first scene, sketched a layout or two, and jumped into finish art right away.

I kept on that way, writing a page or two ahead of the art and finishing as I went along. I definitely went back and rewrote and redrew stuff as the story evolved—sometimes gluing a new panel over an old one, sometimes replacing the whole page. Sometimes it’s just finding a better image, like here:

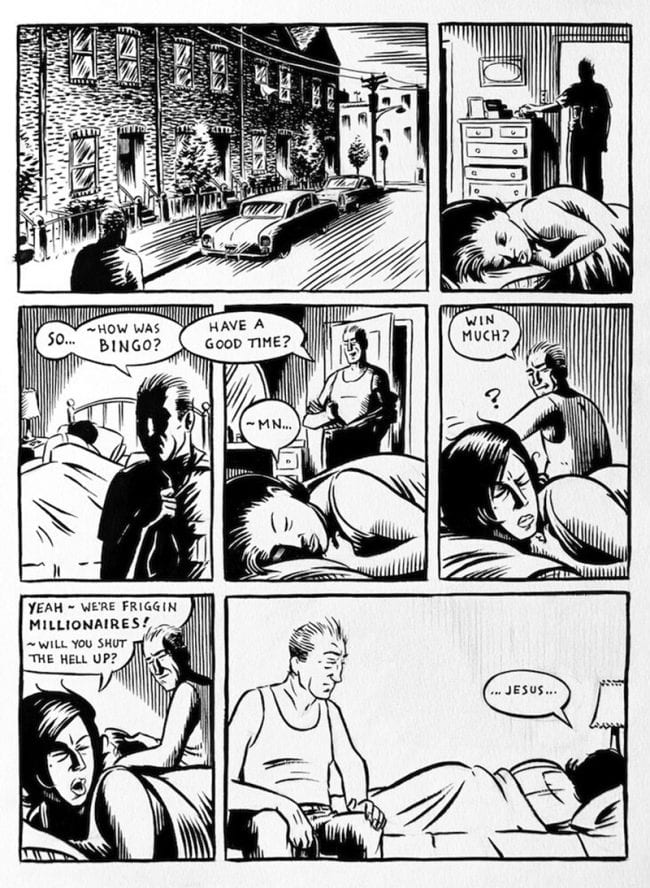

…and other times, it was about writing a better scene. Mostly this involved the evolution of Kate, from “cheating wife” to actual person. There’s a scene at the beginning of the book, after Lonnie has learned that he’s been deceived, and he wakes her up to fish for clues. There’s a conversation that amounts to a struggle for moral advantage, which Kate wins by means of a grumpy handjob. I rewrote that sequence twice—and redrew four pages trying to get it right.

…and other times, it was about writing a better scene. Mostly this involved the evolution of Kate, from “cheating wife” to actual person. There’s a scene at the beginning of the book, after Lonnie has learned that he’s been deceived, and he wakes her up to fish for clues. There’s a conversation that amounts to a struggle for moral advantage, which Kate wins by means of a grumpy handjob. I rewrote that sequence twice—and redrew four pages trying to get it right.

The plot of To Have and To Hold is more urgent and straightforward than that of Good Dog or The Big Wheels, with an ending that offers readers plenty of closure. And at 200 pages it’s also a good bit longer. How has working this way been different for you, and is it a direction you think you’ll carry on in the future?

I’m a terrible writer; is what it is. Big Wheels and Good Dog are just sort of: “Okay, it’s 6:00 AM and we wake up...now what?” To Have and To Hold is the first story with a real plot—it was way more work, but now I feel sort of committed to the idea of beginning/middle/end, so I’ll probably keep trying to do it...

The marriage at the center of the story is in awful shape. Lonnie and Kate are bored, bitter, barely getting by, and without children to soften life’s hard edges (though you give us a few glimpses of what their life together was like in younger, happier years). What does their story say about the postwar American Dream?

Well, it’s the promise of prosperity that fuels Kate’s dissatisfaction, isn’t it? We can see in the flashback panels that she thinks she’s backed a winner. When Lonnie threw his career away, dealing impounded dope with his beatnik friend, she felt gypped. Now they have to watch their expenses; she’s gotta go back to secretarial work to help pay the bills—hardly the fulfillment of the American dream. Tucker, on the other hand, seems like a pretty safe bet: good job, swell dresser, looks a little like Kennedy. If she can’t have the American dream, she can fake it with Tuck, and she’s realistic enough to know that’s about as good as it gets for her.

I really enjoyed getting to know Kate; she’s a wonderful character, easily the story’s most subtle and—awful pun completely unintended—fully developed. Was she difficult to write? Is she a femme fatale?

She wrote herself. Kate started this story as “cheating wife” but I knew as soon as I gave her a line of dialog, that she wasn’t gonna stay there. Her real breakout came in this scene:

Lonnie thinks he’s got her number. He thinks that he’s gonna toy with her and learn the truth, but she shuts him down while still half-asleep and then, when he pushes it, reverses the moral advantage he feels he has and leaves him in no position to question her about anything. Their dialog in this scene told me what my heist story was really about: the slow dissolve of a marriage. Fictional characters (at least my characters) exert a level of independent agency, outside the writer’s control. Once you introduce them, they take on their own personalities and insist on being heard. Kate moved herself out of the fairly insulting role of “protagonist’s object of desire or revenge” to “real person who has her own desires.” The final story is as much about her as it is about him. She has the best lines, too...

She is not a femme fatale, for all the reasons outlined above. A fatale exists only as an object for the hero to desire/pursue/whatever. They aren’t real people; you have no idea what they like or dislike or want or anything. They’re just there to reflect the hero’s own desires.

This never happens to a femme fatale:

To Have and To Hold is dedicated to Eddie Coyle and Popeye Doyle—a worn-out crook and an obsessed cop—two of the early 1970s cinema’s grittiest anti-heroes. Lonnie is cut from the same cloth. What is it about these guys that appeals to you?

Lonnie is one of those guys who is just smart enough to underestimate the people around him—to think he’s got an edge. Feeling like he’s a little smarter than everyone else has given him this frustrated sense of entitlement; he’s his own worst enemy, perpetually biting off more than he can chew. If he didn’t, there wouldn’t be a story, naturally, so perhaps that’s the appeal.

“The consequences of hubris” is a pretty well established theme, going back past Popeye Doyle to...Oedipus, maybe? Lotta antiheroes in between. Lonnie’s got plenty of company there, wherever he is...

He’s also an ex-soldier and an ex-cop forced into “early retirement,” both of which are familiar noir beats. Nevertheless, To Have and To Hold breaks from that tradition in some fascinating ways. Unlike heist films such as The Asphalt Jungle or even Ocean’s Eleven, it doesn’t waste page after page scouting out the perfect crew or glorifying the details of the plan. Was it important for you to update (or upend) certain noir tropes?

He’s also an ex-soldier and an ex-cop forced into “early retirement,” both of which are familiar noir beats. Nevertheless, To Have and To Hold breaks from that tradition in some fascinating ways. Unlike heist films such as The Asphalt Jungle or even Ocean’s Eleven, it doesn’t waste page after page scouting out the perfect crew or glorifying the details of the plan. Was it important for you to update (or upend) certain noir tropes?

It’s less about upending noir tropes and more about telling a story I like. While I love noir and have always wanted to do a noir story, I wasn’t too concerned with sticking to the rules of the genre. I am not the world’s most original writer, and I knew I was gonna lean on some archetypes and clichés—but I wanted to keep ‘em to a minimum—to make my characters as real as they could be in this absurd situation I created for them to run around in. I wanted it to feel grounded in reality. I didn’t want to romanticize any of it. I knew To Have and To Hold was gonna end hard for somebody—that doom was inevitable—but that’s about it.

There’s a bleak, understated quality to some of these crime films of the 60s and 70s (Get Carter, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, The Taking of Pelham 123, etc., etc.) that appeals to me as a writer. I don’t think I could have escaped the lurid, hammy, melodrama of classic black and white noir. I wanted to play with atmospheric lighting and whatnot, but all those weary gumshoes and sexy dames are too entrenched in their iconography for a guy like me to break ‘em out. But these little 70s noir flicks—I could get in there and push my story around without feeling like I was gonna break the genre.

I follow you on Instagram, where you post a lot of in-progress panels and pages. Howzabout telling us what we can expect from you in the future?

I’m working on another noir, this time in 1970s Hollywood. It’s about some low-budget filmmakers who fun afoul of the mob. There’s arson and insurance fraud and general mayhem in the valley.