Breakdown Press is among the most diverse and original publishers of comics in the UK right now, presiding over a small run of books united by their individuality, original story telling techniques, and sheer eye-popping attractiveness. Starting out with the publication of Joe Kessler's Windowpane in 2012, they've stretched out to cover a whole heap of ground – from the politicized future war stories of Lando, to translations of manga from Seiichi Hayashi and Masahiko Matsumoto – and future releases promise to take them even further afield. Having followed their progress pretty closely – and having played records at their Safari comics festival last Summer, a day notable for the incredible variety of art on display and for the amount of free beer I was allowed to drink before 12.00pm – I thought I'd sit down with three of the brains behind Breakdown: Tom Oldham, Simon Hacking, and Joe Kessler, and find out where they've come from,what they're doing here and where they're going, and about some of the challenges and triumphs that come from running a small comics press in today's money-strapped environment.

Breakdown Press is among the most diverse and original publishers of comics in the UK right now, presiding over a small run of books united by their individuality, original story telling techniques, and sheer eye-popping attractiveness. Starting out with the publication of Joe Kessler's Windowpane in 2012, they've stretched out to cover a whole heap of ground – from the politicized future war stories of Lando, to translations of manga from Seiichi Hayashi and Masahiko Matsumoto – and future releases promise to take them even further afield. Having followed their progress pretty closely – and having played records at their Safari comics festival last Summer, a day notable for the incredible variety of art on display and for the amount of free beer I was allowed to drink before 12.00pm – I thought I'd sit down with three of the brains behind Breakdown: Tom Oldham, Simon Hacking, and Joe Kessler, and find out where they've come from,what they're doing here and where they're going, and about some of the challenges and triumphs that come from running a small comics press in today's money-strapped environment.

How did you all get into comics? Are there any particular books you remember fondly from childhood, or any incidents that you can remember getting you started on the path?

Simon: I'd get Tintin and Asterix out of the library when I was a kid, but I never really thought of them as being 'comics' - they were just things I read when I was a child. I remember watching the X-Men cartoon and being excited when the movie came out, but I didn't get properly into comics until I came to London for university and got them out of the library. It wasn't until actual comics were available to me in a real city that I read decent stuff.

Tom: As a kid I read 2000AD and Heavy Metal and then - like with all things - your taste broadens and your appreciation for art matures. I started reading the staples of alternative comics – Crumb and Clowes and stuff like that - that and went on from there.

Joe: My parents had a small and very tasteful selection of comics - they had Raw magazine and Crumb and Chris Ware - so I started off as a snob, buying 'Krazy Kat' and stuff. It was only later that I got fully exposed to The Dark Side.

S: The Dark Side was definitely what got me into it. Being able to go to Forbidden Planet and buy something even if it was awful...

And by The Dark Side you mean..?

S: Superheroes... well no, not just superheroes – just not very good comics.

So what series of events came together that made you want to start Breakdown? Who's idea was it to begin with?

S: It mostly comes out of the fact that me and Tom worked at a comic book shop in London and that's how we met each other. We found out that we had similar tastes and we got on, and quite quickly we had little projects we wanted to run. To begin with it was just in terms of how we wanted the shop to be arranged and stuff like that, but outside of that we wanted to do journalistic endeavours. At university I wrote about comics academically and potentially wanted to get into that angle of things. Then I decided that that was boring and wanted to get into comics journalism, which is obviously isn't really a thing that exists anyway...

Yes, I'm not really here...

S: Sorry dude...

T: “I like the X Men cartoon and you're an idiot... Next question!”

S: The first plausible thing we wanted to do was some kind of magazine covering comics that was attractive and nicely produced and designed. At that point, 5 or 6 years ago, you had all these really plush fashion and design magazines on the racks, and we wanted to marry that aesthetic to content that we were into and that wasn't being covered anywhere else. At some point during this Joe came into the shop...

J: I was just going around chatting people up and seeing whether anyone was into the same sort of thing as me. These guys were then working in Orbital comics and we connected.

T: We were bonded by taste. There was very much a sense of be-the-change-you-want. We wanted to do something that would reflect what was interesting to us.

S: Because our interests weren't being reflected elsewhere. Joe was working on comics that he wanted to publish, and publishing was always the end point anyway. Eventually we became able to fund putting out (Joe Kessler's) Windowpane.

J: I had a show that was already arranged so we rushed it through. We weren't really ready to launch. We did maybe one book in the year after that, so we started slow.

Often the best way, I guess, just feel you way through it.

T: Start small and keep growing. Having put out records and stuff (Tom ran the independent record label No Pain In Pop), it seemed like quite a logical jump to putting out comics. It's where my interests lay and it didn't seem like an insurmountable task.

How do you get hold of the stuff that you want to put out? You're a bit more established now, so do people approach you, or do you approach them?

S: Everything we're ever put out has begun with us approaching someone. It's usually been someone that we like already. Antoine Cosse was a friend of a friend of ours who was putting out comics, so we asked him if he wanted to do something.

J: Me and Antoine met through sports. I went to a book launch of his and me and him were eyeing each other up. We didn't really like each other because we'd played basketball together in Stoke Newington.

There aren't many comics stories that involve sporting rivalries, to the best of my knowledge.

S: He's not very tall either.

T: Is Antoine any good at basketball?

J: No, but he's better than me at comics.

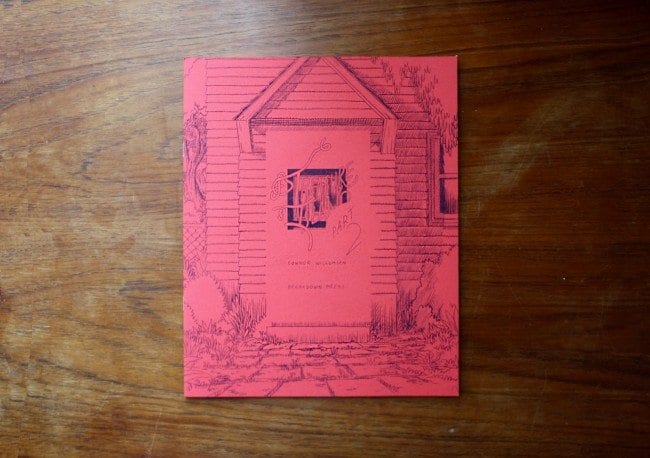

S: Connor Willumsen who does Treasure Island, we spotted his work online and emailed him. I get pessimistic about these things, I always think “He's so good, surely he's got a deal or something?” But Connor was like “yeah, I'd love to.” We couldn't believe that he hadn't been published before. He'd done mini-comics here and there and he'd done an issue of The Punisher which I'd seen people talking about, but there was all this amazing, weird stuff on his website. We didn't meet him until six months after 'Treasure Island' had come out. Now we do get people approaching us by email with all kinds of stuff, but nothing that's made us want to put it out. The reason we bonded in the first place was over quite specific types of comics, so it's very particular stuff we go after.

J: And we can't do that many books either.

S: Yeah, it's not easy to put out tonnes of books in quick succession. Also something we wanted to do with Breakdown - one of its quite specific mantras - was to only put out stuff that we thought was really great, rather than to put books out for commercial reasons or political reasons. So that's another reason not to chuck loads of stuff out in one go.

So do you still scour the internet for stuff?

So do you still scour the internet for stuff?

T: All the time.

S: Being slightly better known than we were a couple of years ago we also have access to people who have better expertise than we do, who we can tap up for stuff. Ryan Holmberg would be the obvious example. It's through him that we're doing all the manga translations. I'd never heard of Masahiko Matsumoto, or quite a lot of guys that Ryan has got lined up for projects we're going to do in the future. Being able to meet him and use his expertise helps to expand the range of stuff that we do.

Do you use the same people to print each book, and how do you go about getting a piece of work together?

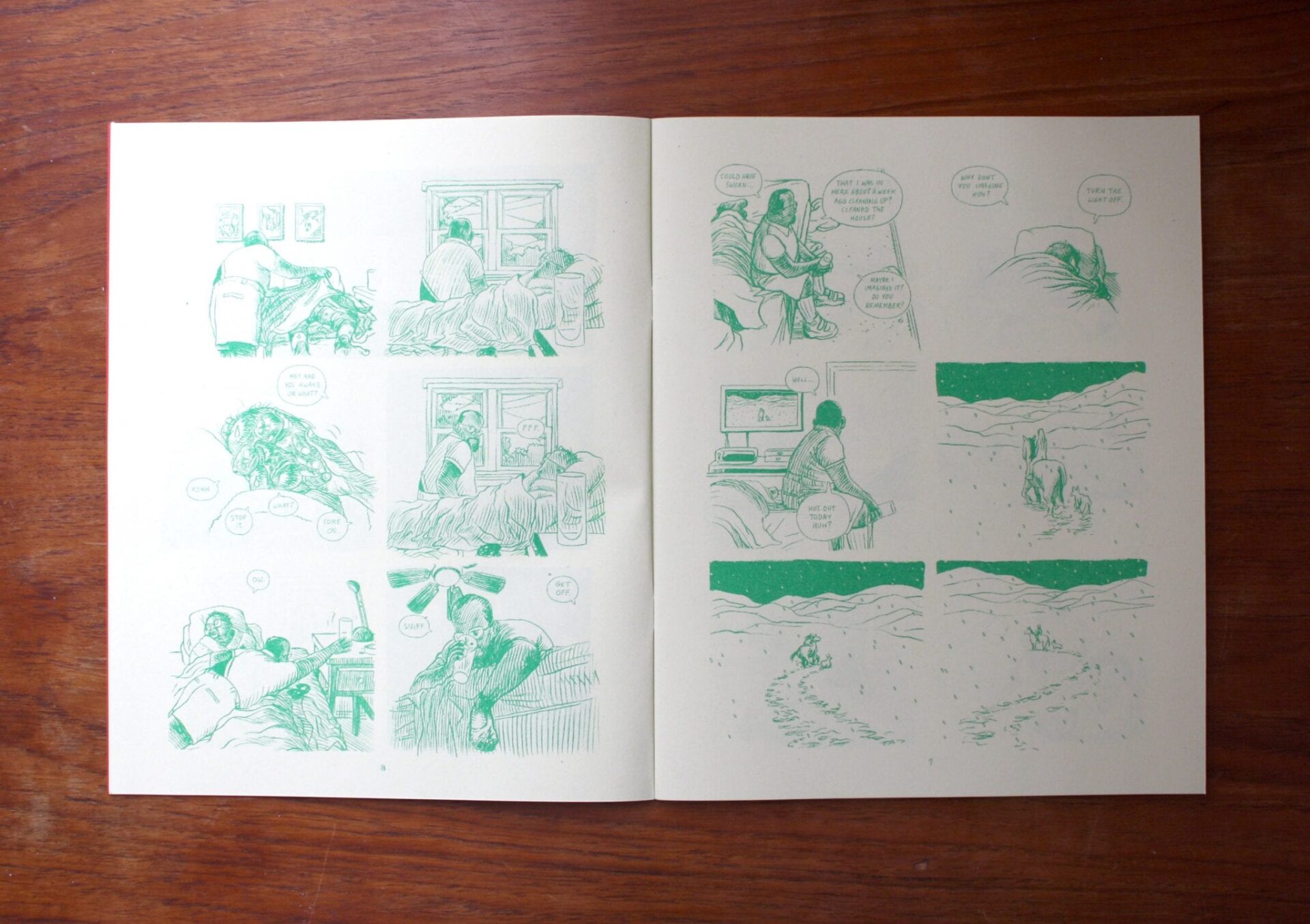

J: All the risograph books we do with Victory Press. We're good friends with Elliot Denny who's the printer and also a very good designer and book maker. He's been amassing printing equipment since he was 13 years old. Me and him spend a lot of time folding paper. The risograph books are small enough in their run that it's possible to make each one by hand. That print process has allowed us to exist really. It's allowed us to do stuff in editions of a couple of hundred - books we wouldn't have been able to afford to do in a larger edition because we wouldn't have had the infrastructure to be able to sell a couple of thousand copies.

S: Me and Tom always have a pretty good idea of what we want something to look like but we didn't have any printmaking experience before we started doing this. Having Elliot there, so we can put something in front of him and tell him what we want, and have him tell us what paper to use etc, makes life a million times easier. It takes the pressure off having to learn skills that are quite complicated.

T: The finished risograph product is really beautiful and that's how we want others to feel about the work – that it's a beautiful artifact. That's really important. For the bigger, offset books – like Lando's Gardens Of Glass and Antoine Cosse's Mutiny Bay - we work with a guy called Joe Hales who's a book designer by trade, so that made the process really easy.

S: I feel as though we know way more about this kind of stuff now.

J: Most of these books have been really easy to do because the artists have done everything. There's just been a few notes and a bit of back and forth about paper stock and what colour and stuff. The manga translations have been slightly different because it's been about repackaging, so there are more decisions that have to be made. You're not going to have input from the artist, so you're having to do more original work. With (Matsumoto's) The Man Next Door, we decided to do each story in a separate colour and to use a belly band, and so on. It was fun though. When you really care about the work you're happy to sink a bunch of time into it.

What about a business model? How you go about getting a book out to distributors, how many copies you need to shift to break even, etc...

S: It varies by book and by project. Festivals are an important lynch pin for us at the moment. Up until summer 2014 we only had four books and now we've got eleven or twelve, so ramping that number up until we're at a point where we can get them out to stores easily is still a process we're going through. Business model is a highfalutin way to put it, but we are serious about it. Breakdown Press is a registered company, so we're responsible about how we put the books out – we make sure we make our money back on them.

Do you have anyone handling your distribution?

S: We have very good relationships with quite a lot of stores here and in the states, that we've generated by emailing them and meeting them at shows, which is how we do our distribution at the moment. We are in the process of organizing more sophisticated distribution networks.

T: The big offset books get printed and we send them out to our network of shops. We're working on getting national and international distribution. But with the risograph books it's different depending on the artist and the project.

S: There's obviously an economy of scale, so we print significantly more of the offset books than the risograph books, which brings the unit cost down which means we can afford for the distributor to take a bigger chunk. Some of the risograph books – in fact most of them – we couldn't distribute because it would be too much money considering all the discounts you have to give. It astonishes me how many small publishers you speak to that don't operate under those assumptions.

One would think that it's kind of suicidal not to...

S: But this is a labour of love. It's all about our passion for this stuff...

T: Ding! Mark 'labour of love' off the interview cliché bingo card! It is difficult to say this stuff without sounding a bit hackneyed and clichéd but the reason we're publishing these artists is because we really believe in them and we think their work has value. We want them to make a living out of their work, so a bigger, more profitable business helps us contribute to that.

At the end of the day, comics are the winner... Do you think there are any factors that your books have in common? I can think of a couple, but I'm not going to tell you what I think they are.

T: Yeah, they're all really fucking good!

Ding! That's another one...

J: I think they're all quite personal visions. Every artist has a strong identity.

T: They're united by their dissonance.

S: It's not that we have a list of things to tick off when we're choosing a new project. I'm sure it's all unconscious innate things that we all agree on. We have the same influences - we're all fans of 'Raw' magazine and so on – so they must unconsciously feed into an agreement of what constitutes a Breakdown comic.

J: What do you think the through line is?

They're all somewhat melancholic.

S: Interesting...

Even Lando's work has a real sense of loneliness to it...

S: Yeah, and (Seiichi Hayashi's) Flowering Harbour does certainly...

That's probably the loneliest thing I've ever read in my life.

J: (Inés Estrada's) Sindicalismo 89 isn't very lonely...

I haven't read that one yet, so maybe you're branching away from the loneliness dollar.

T: They all have – maybe not Windowpane so much – but they all have isolation as a theme.

S: Yeah, if not loneliness then isolation definitely.

J: I think Sindicalismo, Windowpane and The Man Next Door fall outside of that.

T: Sindicalismo and The Man Next Door are dealing with communities being separate from each other, even though they're contained in the same building.

J: That's a lonely man's interpretation.

T: It's true, I can't help but see things through the prism of my own unending loneliness.

S: Isolation is an interesting theme that speaks to me in many ways, but it's certainly not something I was conscious of that might be a theme in our comics.

As you say, these things are unconscious and if you have three guys that are of a like mind about stuff then that's going to come through.

S: I guess there's a lot of that in our influences - Chris Ware and Dan Clowes and Spiegelman and so on.

There does seem to be a lot of it in alternative cartooning.

S: Ding! Cartoonist talks about isolation.

T: Do you think there's anything from the technical process of making comics that links the books? I think there is but I can't think of a way to articulate it.

S: I think Breakdown books are quite classically laid out. All the artists use regular panel grids.

J: So far...

S: I don't think you'd necessarily call them experimental or avant-garde in terms of the way the artists use pages, but I would still call the content experimental. I think we are all interested in narrative as much as anything else. They don't have to just look good and they don't have to just read well, you can have both. What me and Tom have always been quite passionate about in terms of comics is them doing everything, rather than just one thing.

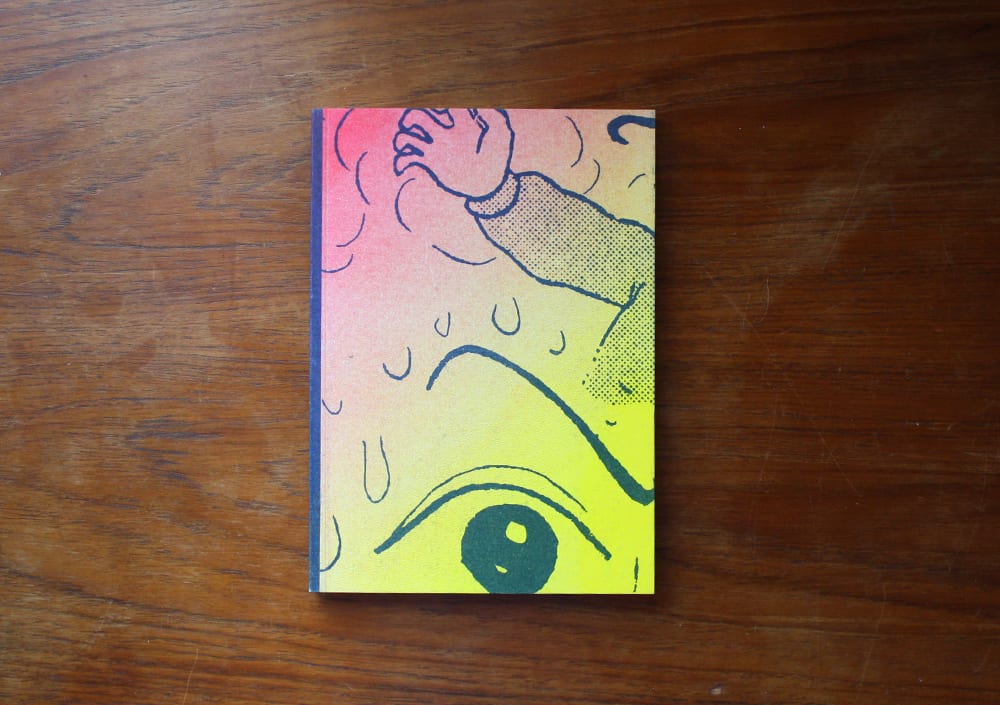

J: I think there's an engagement with process that they all have. (Conor Stechschulte's) Generous Bosom engages with print in ways that most other graphic presentations don't.

S: Windowpane does that as well.

J: In almost all the books there's an engagement with the book as an object.

T: That's what I was going for.

An engagement with the eventual object shapes the way the narrative is told...

S: That's anther thing about making a point of producing beautiful objects: however digitized comics have become, the physical versions make a point of being nice. Which isn't necessarily true of other page-based art forms.

J: The book is the final thing. It happens in children's books as well - the object and the content are completely tied together.

So, let's talk about the Japanese translations. For a start how did you get in touch with Ryan Holmberg?

S: He came into Gosh about doing an event, because Seiichi Hayashi was in town and he was doing one at SISJAC (Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures, based in Norwich) and wanted to do one in London too. We later emailed him to say that we'd like to to work with him and that's more or less it. We went for dinner and showed him the stuff that we'd done and he was quite amenable.

J: You go to Japan and go into one of those big comic book shops and there are walls and walls of stuff. I mean, I'm paying attention but I just have no idea what it all is, because there are just endless books. I want to know, though...

And he's your path through all that stuff. Did you previously know anything about (Hayashi's) 'Flowering Harbour'?

And he's your path through all that stuff. Did you previously know anything about (Hayashi's) 'Flowering Harbour'?

J: I knew some Hayashi stuff from Japanese editions but not that work particularly.

S: He suggested that one. The first year we had a table at Comics Arts Brooklyn in New York Gold Pollen - the PictureBox collection of Hayashi's work - was the book that we all bought and went 'Woah!'. As soon as Ryan suggested releasing some Hayashi's stuff we were very up for it. Ryan hasn't suggested anything to us that we wouldn't be interested in doing. Everything he's suggested has been something that we're excited about. In terms of design and how the books look, that's all come from us. Joe has done the work there...

J: … And (photographer and designer) Alex Johns

They look nicely distinct from the rest of the line as well.

J: They're very different pieces of work in terms of format and everything.

T: In the future we're going to keep doing the Japanese risographs in the same format, but we also have plans for longer pieces that we're going to do as offset books. The next thing that we've got coming up is a collection of stuff by a guy called Sasaki Maki, who does psychedelic stuff from the '60s. I think he's famous for doing kid's books now. We're going to be putting out about 200 pages of his stuff.

What about internet models of publication? Is that anything you have any interest in?

S: I suspect the site will evolve to some extent in the not-to-distant future. I'm quite happy with how it looks and it serves its purpose, but I'm sure we'll start selling digital versions of our books at some point.

T: We plan to. In terms of digital comics and comics online, our heads aren't in the sand about it, despite us being so into the idea of physical product. But at the same time it's all done on a case-by-case basis.

S: Connor Willumsen's stuff is already online.

I read his online comic about Can this afternoon. Fantastic, a really good use of the medium.

S: 'Treasure Island' was originally put up online and that's how we ended up seeing it. Presumably it was designed to be digital. I know loads of his other strips are but that doesn't mean they won't also work physically. I think we all have more of an interest in physical comics and print techniques than we do in digital comics.

J: It's not really clear what our role would be in terms of distributing them and promoting them.

S: I do read comics that are online but I do it because they're free. The way these things usually work - the way people monetize online stuff - the physical thing exists and then in order to make it accessible to people who may not have a bookshop near them, or don't want to pay postage, or who prefer reading on an iPad, you also make it available digitally. That's fine, but if it compromises the final work then why bother?

T: We're very aware that the internet exists, but we're not entirely sure how to move forward with it. When opportunities expose themselves to us we'll look into them.

What lessons have you learned from other publishers, and do you learn anything from working in comic shops?

S: Tom and I have worked in various comic book shops for between four and five years now. It's really useful to see what sells and what doesn't, but then you ignore that as soon as you have a project that you think is cool.

J: Because the best shit doesn't sell.

S: It's a depressing fact of life. The point of that being that you have to put the cool things into the hands of the right people yourself, rather than relying on them to bump into it.

T: Working in a shop is interesting because you're on the front line of a lot of different communities within comics, and it's interesting to see what concerns people and what people are buying. Whilst Breakdown doesn't have a manifesto, one of the things that is constantly on our minds is how to build an audience for our comics as well as selling them to an audience that already exists.

S: Our project from the start has been not only to give ourselves something to do, not only to help pay artists to keep doing what they do, but also to create an audience for this stuff. I do think that the more quality work is produced the more the audience expands.

Something that the best independent record labels have in common - say Sub Pop or Broken Flag, or whoever - is that people will see the label and go “I'll buy that because it's on that label and I trust their taste.”

S: PictureBox was like that for us, I think.

J: I was interested in everything they were putting out.

S: To a similar but slightly lesser extent, because they put out so much more stuff, Fantagraphics and Drawn and Quarterly are generally really good. Famicon as well, which is Leon Sadler and his brother's thing. We're not making a point of saying “we want to be like these people,” just taking on board a swathe of things we're interested in.

So what's coming up next?

T: we're doing the Shaky Kane book next. It's called Good News Bible and it's his complete strips from Deadline, which was a comics magazine in the early 90s that mixed music and comics and popular culture. It was where the most interesting genre comics people were working in this country. People like Brett Ewins and Jamie Hewlett. Coming back to Shaky's work it's really interesting how politicized it is. As a child reading it I didn't pick up on that, I just thought it was balls-out nuts. The other thing we've got coming out is the Sasaki Maki book.

S: Which should be out reasonably soon. It's our next collaboration with Ryan Holmberg, so there'll be an essay by him in there and an afterword from Haruki Murakami, as well, who's a friend of Maki's. It's going to be the first of several larger graphic novel format translations of Japanese stuff. The plan is to do riso translations and book translations, maybe two of each a year for as long as Ryan will have us. All these guys are people we're massive fans of and it's a privilege to work with them. Oh, and there's going to be a Safari 2 as well...

Okay, so Safari was the convention you organized last year, what led you to want to put it together?

T: We wanted to try and build the audience for the sort of work Breakdown produced and to try and help build a bit more of a community between like minded comics creators and artists. Also we wanted to try and present this kind of stuff as a distinct entity, not watered down by other kinds of comics.

S: We go to some great shows. We go to Comic Arts Brooklyn every year and it's an amazing show, but nothing lives up to it in the UK. Safari isn't anywhere near the scale of CAB, but we wanted to take that vibe of just picking the stuff that's great and being very selective about it. Everyone was very nice about Safari, particularly the people that exhibited. It's always very complicated organizing these things. Tom has put on music festivals before, but it was quite new for me to orchestrate something with that kind of complexity. Turning up on the day you've got no idea what's going to happen. The real enjoyment of it doesn't come until the end of the day when people come up to you and say “yeah, we sold loads of stuff and had a great time”.

T: Part of the fun of doing comics is that you get to have fun and hang out with your friends. That's what Safari was and will continue to be. Hopefully in the coming years we'll make the event a little bit bigger and introduce more arts and music stuff as well. Comics will always being the central focus though.

S: Comics festivals are kind of interesting because really you're just sitting there selling stuff. I always have a good time at those things, but it's quite a weird environment.

J: It would be nice to sit in a context that isn't just comics.

T: It was interesting earlier when you asked about what publishers had influenced us. I ingest more art and ideas from outside of comics.

J: The thing about the comics convention is that the context is quite finite and crystallized. It would be nice to broaden that context a bit, not just in terms of conventions but in terms of what comics are. Comics are a broad medium and it would be nice if that aspect could come across.

T: As with 'Deadline', those other mediums like music and film have connections to comics and that's an area where you can grow an audience. Comics are always going to be our main focus, but we're going to publish other books and get behind other artistic projects because, fuck it, why not?