Here's one you may have heard:

Drew Friedman, the cartoonist, is on the dais of the Milton Berle Room, the largest space at the Friars Club. Various Friars have gathered to celebrate the publication of Friedman’s Even More Old Jewish Comedians, the third and final installment of his elegant series portraying dinosaurian Catskills alumni. The illustrator unfurls his prepared remarks. He recounts his well-worn tale of the time that Jerry Lewis phoned him upon publication of the first Old Jewish Comedians, in 2006. (“Like it?” the comedian squeaked. “I loved it!!!!”) He pays respect to Mickey Freeman, who lived to cherish his depiction in book #1 but not his dedication in book #3. And, naturally, Friedman acknowledges some of the luminaries gathered at the Friars Club: Larry Storch, Al Jaffee, Eddie Lawrence, and…is Abe Vigoda here? “He’s in the bathroom with Gilbert Gottfried!” someone yells. Wise-ass.

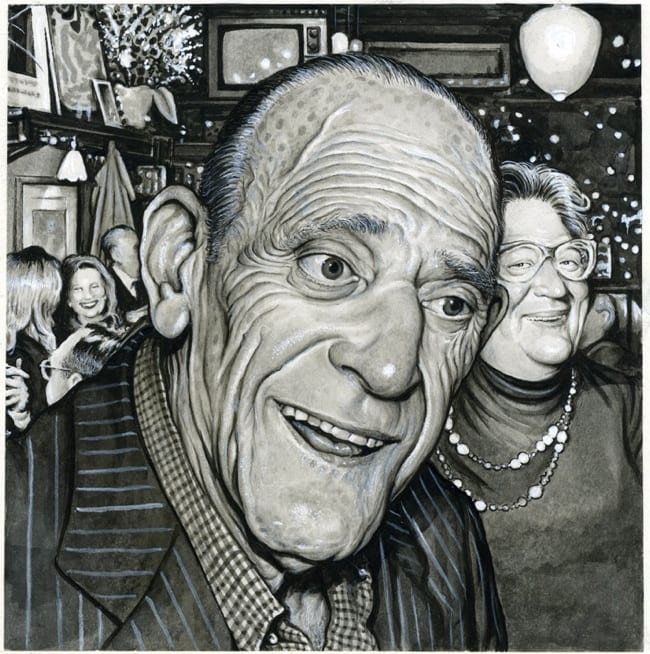

As the cartoonist continues with his address, there is a ripple in the crowd: Vigoda, having heard his name from the back of the room, is slowly cutting a path to the stage. After what seems like an eternity, the actor—Salvatore Tessio himself—joins Friedman at the podium. He is 90 but, as his Friars pals might say, doesn’t look a day over 114. Vigoda speaks away from the microphone—joking, praising the book, and singing with geriatric sweetness. The illustrator stares into the crowd. “So this is the lot I’ve stuck myself with?” he appears to be thinking. Finally, the podium is relinquished to Stewie Stone, the ruddy cover star of the new book and the evening’s master of ceremonies. “Abe,” the comedian says, “was the ground cold when you got up this morning?” (The room roars.)

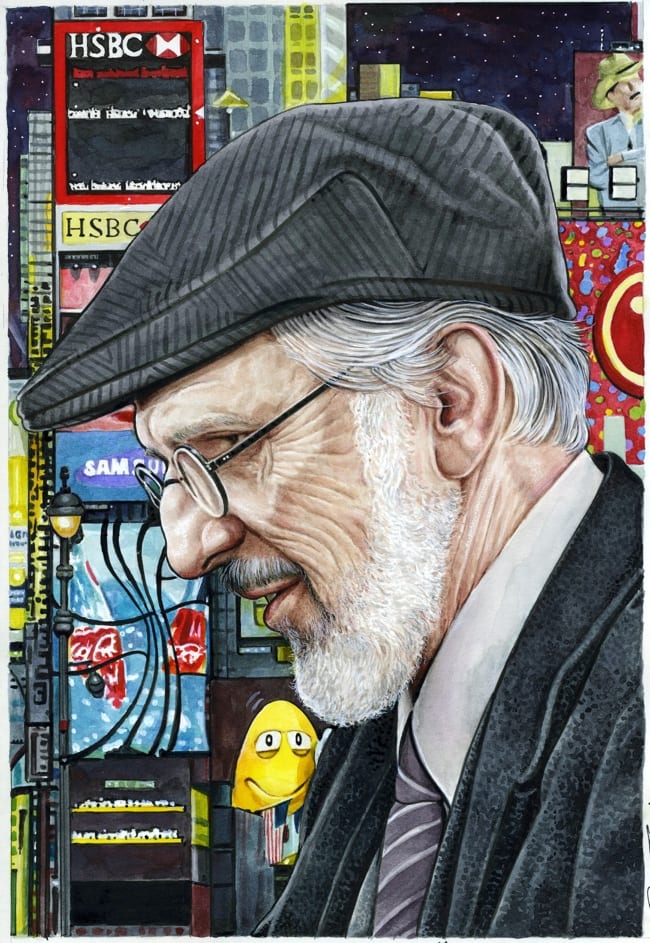

Just a few hours earlier, Friedman walked into the Second Avenue Deli for brunch and an interview. New York’s tug-and-pull between nostalgia and commerce has moved the restaurant away from its namesake street, so that the Second Avenue Deli thrives, on 33rd Street, as a kind of living ghost winking at its former self. Friedman is best known for his work as a commercial illustrator, his beautifully woven and oftentimes unbecoming studies of the famous appearing in virtually every major American publication. (The New Yorker’s Obama-as-Washington inauguration cover, a brutal Oprah-at-Auschwitz portrait for The New Republic, untold cover images for The New York Observer….) Yet throughout his career, and culminating in the Old Jew books, his more personal work has focused on those human equivalents to the Second Avenue Deli. Friedman’s America is an ultra hip nostalgia show, placing his heroes in the glaring light of revisionism, parody, subversion, or old age.

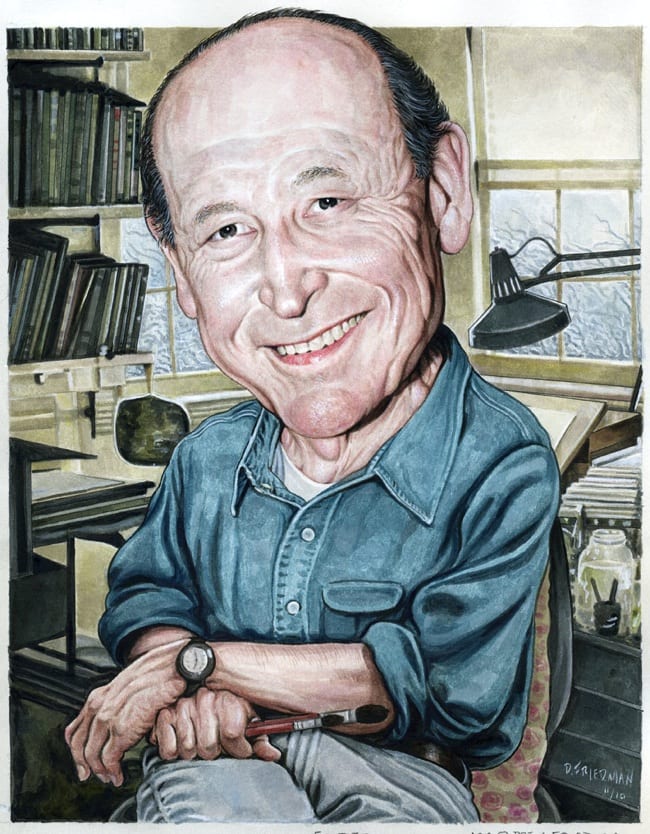

As he made his name in the early ’80s, this approach led the artist to brooding fare such as a caustic Andy Griffith Show racial parody, or a portrait of his favorite Stooge strangely placed on the cover of Al Goldstein’s Screw. (Apparently, back in 1982, nothing got a man sexually charged like Shemp Howard’s face.) Yet his recent drawings are free of such young man’s bile. The stipple style that was once Friedman’s trademark was long ago replaced by gentler painting, as if the artist dragged his once-seedy subjects into the light of day. Although he continues to present people in less-than-flattering terms—nobody’s about to use a Drew Friedman portrait as their JDate profile—his affectionate undertone continues to push its way to the fore. The Old Jewish Comedians series from Fantagraphics is frank yet loving. Where a lesser caricaturist might be tempted to exaggerate the comics’ physical flaws, Friedman looks upon them as he would beloved relatives. Mel Brooks beams in such extreme close-up that the wrinkles around his eyes appear to smile. A panicked Buddy Hackett turns away from a microphone, gripped by stage fright and thrill. Victor Borge holds his ancient hands aloft—the great maestro at rest. Throughout the books, the performers are identified by both their birth and stage names, the latter rendered as parenthetical afterthoughts, like superheroes unmasked. Outside of introductions and acknowledgment niceties, no other text appears in the books. It does not need to.

Friedman is a former New Yorker who for years has been stationed in the Poconos. He is tall and slender, perhaps not ugly enough for his chosen profession. A second generation humorist, his father is Bruce Jay Friedman: a novelist (Stern), playwright (Steambath), screenwriter (Splash, Stir Crazy), and ferocious short story writer, whose characters are often driven by an obsessive compulsive weirdness predating Larry David. His father’s fame gave the young illustrator access to extraordinary comedy heroes including Groucho Marx, Terry Southern, and William Gaines. Yet at the deli, Friedman credits his kinship with folk like Vigoda and Stone on less exotic origins. “Our relatives were funny—funny because they were crazy,” Friedman says. “Which is why I’m very comfortable with these old Jewish comedians. Socializing with them at the Friars Club is a throwback to going to the seders and bar mitzvahs when we were kids, and encountering these lunatics.”

Jay Ruttenberg: The Second Avenue Deli is probably the worst place in the city to try and record an interview.

Drew Friedman: Should I just tell everybody to shut up? Just announce it. “All you Jews, just shut up! Keep it down!” The people that were sitting there—I didn’t like. That one guy had a puss on. How many of these people do you think are gonna be at the party tonight? How many are Friars?

Are you a Friars member?

No. You know, it’s mostly dentists now. Dentists, accountants, chiropractors…. It used to be all show business. It was started by George M. Cohan, so it was mostly theater, connected to Broadway. Little by little, it drifted toward comedians. Georgie Jessel and Eddie Cantor became Friars, then Milton Berle. So it became a comedian club, which it still kind of is. But now it’s also a lot of people who want to mingle with show business people, so they join the Friars Club.

You’ve just published your third Old Jewish Comedians book. How did the project originate?

I’ll tell you exactly how they came to be. The editor, Monte Beauchamp, does these Blab! books for Fantagraphics, and he wanted me to do one. The money wasn’t great, but he said I could do any kind of book I wanted. It would take upward of a year to do. So I thought, What can I work on between assignments, that I would really enjoy? What do I like drawing the most? Well, I like drawing comedians and I like drawing old Jews. So I just put that together and had Old Jewish Comedians. When I did the first book, I thought I was just doing that one. So I did the most famous ones first: Milton Berle, Jerry Lewis, the Marx Brothers, Phil Silvers, Danny Kaye. But the book sold really well, so they asked for a second one. This is the third and final one. It’s not that I’m running out—I have a list of over 100 more that I could do. But I don’t want to start scraping the bottom of the barrel. I want to move on.

At the same time, the first book has a lot of pretty obscure people. I had never heard of Menasha Skulnik before.

Well, he was a popular Yiddish theater actor. He actually starred in a couple Broadway shows in the ’60s when he was older. He’s legendary—but most people never heard of him. I guess it was a mix. The first book, I also gave myself restrictions. No females.

Like the old Friars club.

Right. Of course, now you can be female and be a Friars. You can be anything and be a Friars, as long as you wear a jacket and pay your dues. But I didn’t have women in the first book—my wife wasn’t so thrilled about it. I reasoned that there really weren’t that many Jewish female comedians back in that day. The other rule I gave myself was to keep them born before 1930, just to make them really old.

Years ago I knew a black cartoonist who claimed he was only comfortable drawing black people. Do you have an easier time drawing Jews than gentiles?

Not at all. I like drawing interesting faces. It could be anything. But if there was a book about old Catholic comedians, it would be a pamphlet.

It’s the opposite of the joke about the Jewish sports stars magazine.

Exactly. You know, a couple people suggested I do old Italian comedians and old black comedians. My answer is always: I’m sticking with the Jews. But you know, this is the last book. I’m not doing it anymore, because I’m becoming an old Jew myself.

Do you like all the comedians you draw?

I’m not a fan of some of them—I’m not gonna mention names. But there’s some I really don’t like. There’s this one guy who was a storyteller, and I find him incredibly annoying when I watch the old clips. I can only watch a couple minutes before I get bored. The punch lines are never funny, the whole shtick is cloying. But he had a huge career. There’s another guy, always mintzing around—very annoying. There’s some you just want to tell to shut up. But they’re in your face, and that’s what they all have in common. They just love to perform, even when they get old. They never stop, to the very end. It’s always performing, always on. I wanted to capture that.

Jerry Lewis is kind of the ultimate example of that.

Yeah. He’s 85 now and he told me, “I’m gonna outlive George Burns.” Who made it to 100. Jerry’s goal is to be the longest lived comedian.

How did the comedians, such as Jerry Lewis, respond to the first book?

Fantagraphics sent out the books to some of the living comedians. I started getting phone calls. The first was from Mickey Freeman, who was on Bilko. He was thrilled—delighted. Then an hour later, Freddie Roman called. He was thrilled too, and happy to be opposite Jack Benny. The third call was Jerry Lewis. He didn’t sound so delighted. He left a phone message: “Hello Drew. This is Jerry Lewis. Please call me back.” And he leaves his phone number—twice. So I turned to Kathy [Bidus, Friedman’s wife] and said, “Jerry does not sound happy. Oh, shit. What did I do? Was it because I didn’t put him on the cover? Because I gave him a stupid expression?” I got up the nerve to call him back. I said, “Hi, Jerry, did you like the book?” He said, “Did I like it? I loved it!!!! Jesus Christ, what a book! Holy moly!” He went nuts on the phone.

Jerry’s a guy with a horrible reputation. When I interviewed Joan Rivers, she told me he should be electrocuted.

Jerry’s a guy with a horrible reputation. When I interviewed Joan Rivers, she told me he should be electrocuted.

Well, I found Jerry to be completely delightful. Just great. He’s very inquisitive about the process about what I do. He asks, “Drew, how do you do what you do?” So I say, “Jerry, how do you do what you do?” You gotta butter him up: “I especially love drawing you, Jerry.” But a lot of them hate each other. It’s very funny. You bring up one comedian to another comedian, and there’s venom. It’s amusing to me. There’s nothing funnier than angry comedians. Nothing better! That’s why I enjoy Jack Carter so much. He wakes up angry. He’s the one comedian who hated the book.

What did he say?

A friend of mine was gonna interview a bunch of them about the book for the L.A. Times. He called Jack Carter, who hadn’t seen it yet, and asked “How do you feel about being in a book called Old Jewish Comedians?” Jack said, “Old?!?” Jack is 88. And he said, “And Jewish? I don’t work Jewish!” So already, he was pissed off. Then he saw the book and he was really pissed off. He said, “Why did he give me that stupid expression? And what’s with all the liver spots? Tell him to draw me again.” I said, “Only one portrait per Jew.”

It’s interesting that one of Carter’s arguments was that he “doesn’t work Jewish.” It’s an issue with that older generation. There’s a story about Rodney Dangerfield asking Adam Sandler why he performed his “Hanukkah Song”—he thought it would be bad for his career if people knew he was Jewish.

[Dangerfield] never did Jewish shtick. A lot of them never work Jewish. It’s unnecessary.

Yet your books identify the comedians by their real names, with their stage names in parentheses. It’s like listing Clark Kent over Superman. You’re outing them.

Well, outing them with the names. A lot of them really want their show business name to be the name that people know. They want it on their tombstone—show business is their life. And overall, 95% of them changed their names. In order to work clubs across the country, they had to. A club in the Midwest or even New Jersey wasn’t gonna book Benjamin Kubelsky, but they’d book Jack Benny. And nobody changed their names back. Don Rickles did not want anybody to hear that his real name was Archibald.

He complained about that, right?

I heard from Don’s people. They said, “Don is not happy. You said his name is Archibald. His name is not Archibald, it’s Donald.” At the time we did the research, every website said Archibald Donald Rickles. You go there now, none of it says that. I don’t know for sure if his name was Archibald, but some of the other comedians I discussed it with said, “Yeah, that was probably his [original] name—Archibald was a popular Jewish name in the ’20s.” But you know, the King of Venom doesn’t want to be outed as Archibald. Imagine he gets a heckler: “Hey Archibald!” It’s not good. Everybody knows Don Rickles is Jewish, but he’s another guy who doesn’t work Jewish. Don Rickles is brilliant and he doesn’t need to.

Were other comics angry about you using their birth names?

Sid Caesar. We found out his name was Isaac and he claims it’s not—it’s Sidney. He called Fantagraphics and ratted out Kim Thompson, the publisher, for half an hour. Complaining, yelling. But during the yelling, he also did comedy and Yiddish shtick. I said to Kim, “I’m jealous—I wish I had gotten that call.” The last thing I wanted to do was piss off Don Rickles or Sid Caesar, [both of whom] I adore. Most of them were happy with their portraits.

Didn’t Woody Allen complain about your drawing of him?

In the Observer. He actually wrote a piece for the Observer about his love for the Knicks. They assigned it to me, so I did a close up of Woody dressed up like an old sports reporter, with liver spots and freckles. When he saw it he was livid. His sister called the Observer and said, “Woody is really angry. He’s never going to work for you again.” I felt bad about it. I thought Woody would enjoy it. But people just don’t have a sense of humor when it comes to themselves.

Well, you’ve been accused of drawing the worst in people.

I think people have misread my work. In some cases, yeah. When I was younger, I was a wise-ass. Some of that stuff went too far. I know that now—I knew it then.

Like what?

Some of the stuff dealing with race possibly went a little too far. Like falling back into these clichés of exaggeration with black people. Or Jewish people. It gets you in trouble.

At the same time, isn’t that part of the job description?

It can be. But you know, a lot of people don’t want to make waves. I wanted to make waves. I got sued once—by Joe Franklin—and never wanted to get sued again. Back then I had no money. Now, I don’t want to get sued and spend money on lawyers.

How much did Joe Franklin sue you for?

He sued me 25 years ago for $40 million. A reasonable sum. At the time he sued me, I had about $9 in the bank. I’ll qualify this by saying that we’re friends now. In fact, I don’t even think he remembers suing me. But he sued me for over $40 million over a comic strip I did about him shrinking. He’s a little touchy about his height, cause he’s kind of small. But he sued the National Lampoon Company, which ran the comic in Heavy Metal. They basically covered the expenses, so it didn’t cost me anything, and it got me some publicity. The judge dismissed it before it went to trial, which I had mixed feelings about. I thought it would be an amusing trial. But sure enough, Joe and I are friends now. I go to his office.

Is it as messy as legend has it?

Oh, yeah. It’s like the Collyer Brothers. You walk in there and think he must have been there for 50 years to have accumulated all this stuff. But the funny thing is, he’s only been there for a decade.

(continued)

I’m a fan of your father’s writing.

Thank you.

This may be impossible for you to answer, but how do you think it influenced your own work?

I’m not sure if his writing influenced me. But as a person, of course. He’s a guy that basically did exactly what he wanted to do. Also, to this day, he’s able to jump around from genre to genre: Short story writer, journalist, novelist, playwright, screenwriter, interviewer, etc…. It all falls under writer. That was a huge influence. Cause I think it’s hard to pinpoint what I do, too. I’ve done comics, caricature work, straight portrait work, Jewish comedians, sideshow freaks and some writing, as well. I never wanted to be pigeonholed, and he was a big influence as far as that’s concerned. Obviously, the sense of humor’s gonna rub off on me—my mother’s, as well. Growing up with him and just being around his writer friends, seeing his shows, and reading his books, it was bound to rub off. I don’t know how to describe it. I guess it had a huge influence. It had to. Also, I’ve never held a job. He was a magazine editor, but he finally retired to be a full-time writer. So he was just always home writing. That’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to stay home.

You must have sensed the discipline in that, too.

Yeah, that too. He’s very dedicated. He’d stay up all night [writing]. Or he’d disappear for days at a time, just to concentrate on what he was doing.

Your father isn’t a comedian, but his writing is very funny. Often, people behind funny work are brooding in real life. Was that the case when you were a kid?

No. He’s a humorist—he thinks funny. It was a very funny household. It’s not a dark sense of humor. Our relatives were funny—funny because they were crazy. You know, our Jewish relatives in the Bronx. Which is why I’m very comfortable with these old Jewish comedians. Socializing with them at the Friars Club is a throwback to going to the seders and bar mitzvahs when we were kids, and encountering these lunatics.

A lot of comics from that generation sort of professionalized the “wacky uncle” figure.

Yes. A lot of people buy into the haunted smile concept—you know, the smile behind the frown. They came from shtetls and poverty, so they had to be funny and they had to laugh. I’m not sure I buy into that. I just think they’re a bunch of hams. They like to be funny, they like to perform.

Do you think it comes from being mama’s boys? Wanting to please Jewish mothers by making them laugh?

I guess so. The best example is the Marx Brothers. You know, Minnie Marx pushed them into show business. They were kind of resistant at first. Gummo went right out—he retired in 1918, I think. He never made the movies, quit before Broadway. I still put him in my book. Zeppo, too. Groucho’s gone on record that Zeppo was the funniest brother and Gummo the second funniest.

I don’t know about that. We’ve seen what Zeppo can do.

Yes—the brilliance of Zeppo. But I’m a Zeppo fan. I’m one of the few guys who applauds when Zeppo comes onscreen.

You actually met Groucho Marx when you were a kid. I beg you to tell me about this.

It’s something that we took for granted. Like, so what—Groucho Marx. But all these years later, in retrospect, not many people can say that they met him when they were teenagers. The thing is, I met him three times. I first encountered him in 1970, when the show Minnie’s Boys was on Broadway. Groucho was a consultant on the show and was there every night, in the first row. So at intermission, I went right up to him with my Playbill. Then a couple of years later, ’73, he was doing ads for Teacher’s Scotch—print ads. His girlfriend knew my dad from parties in New York and whatnot, so we went to a party. Groucho was there and talked to my dad.

Was he a fan of your father’s work?

Possibly—he knew who my dad was. Groucho’s mind was still sharp. My dad’s movie The Heartbreak Kid had just come out. Groucho knew it, said he loved the film. Mostly it was through Groucho’s girlfriend, Erin Fleming. A lot came out about her later, but she seemed nice. So two years later, we were summering in Los Angeles and she called my dad and said, “Groucho would love to invite you to his house for the afternoon. He loves young people—loves kids.” Most of the people that visited Groucho’s house were his old pals like Georgie Jessel, songwriters, comedy writers. But she was inviting a younger crowd, like Elliott Gould, Bud Cort, Sally Kellerman. So we all went to Groucho’s house for the afternoon.

What was his house like?

It was in the Hollywood Hills, a modern house. Built in the ’50s. Beautiful house, but not a huge mansion. Like a one-level, looking up at the Hollywood sign. He greeted us at the door. Groucho comes to the door, real slowly. He’s wearing shorts and has a Marx Brothers shirt, with little caricatures of the Marx Brothers—very surreal. This was ’75, so my brothers and I had long hair, down to our shoulders. So he looks at my dad, and he looks at us, and he goes, “It’s a pleasure to meet you Bruce, and your three lovely daughters.” We went in for a few hours. He did all his old songs, “Hello I Must Be Going” and everything. His nephew Bill—Harpo’s son—was on the piano. It was great. We had an amazing time. Dennis Wilson, the Beach Boy drummer, walks in, goes up to Groucho, and says, “It’s a pleasure to meet you, Sir.” Groucho looks at him and goes, “It outta be!” My brother Josh asked Groucho if he remembered a theater in Great Neck, which had an old organ in the back. And Groucho interrupts and says, “I have an old organ myself.”

Was it like when Gilbert Gottfried goes on Howard Stern imitating Old Groucho?

“In my day….” No, we didn’t get any of that. To be honest, I never picked up on that. I think Groucho really liked young people. He really felt at home with the protestors in the early ’70s. He hated the Vietnam War, hated Nixon. He was out there—a diehard liberal to the end. He fit in as a counter-culture hero and really loved it. He was very accessible in the ’70s, which is why it seemed like no big deal to see him. In New York, he would be turning up at things.

As a kid you also knew Terry Southern. Was he a larger than life figure?

Well, I was pals with his son Nile, and Terry was good friends with my parents. I first met him in the summer of ’67—the summer he was on the cover of Sgt. Pepper. I knew he was a writer and the guy who wrote Dr. Strangelove. But you know, I was 8. I thought he was a very sweet guy, very attentive to his son. I remember Nile and I wanted to spend the night outside in a tree house, and he was very concerned—he thought it would be too cold. He was a really attentive dad. I got a couple calls from him over the years. Back in the ’80s, he wanted to get into Spy, so he left me a long, rambling, Terry Southern–esque message. There was static, like he’s calling from an airplane. My dad was really close to him. He had a circle of guys. Mario Puzo was a really close friend as well. And Joseph Heller and Jules Feiffer.

Jules Feiffer must have been one of the first illustrators you knew.

It was fun for me, cause I loved his cartoons.

Were you always geared toward this career?

Yeah. I was drawing from the get-go. I knew early on that all I wanted to do was draw. Like really early—2, 3, 4. I was just always drawing. At school, I would draw all over my desks and books, obsessively. And I had favorites. Everybody had MAD. New Yorker cartoons, animated cartoons, Warner Bros. And Feiffer. I loved his stuff, so it was like, wow, my dad’s friends with this guy and he’s a cartoonist. So that was a thrill. My childhood goal was to be a contributor to MAD. I wanted to be in the Usual Gang of Idiots—one of the idiots. And to work for Topps Bubblegum Company. So I’ve achieved both my goals. But I also wanted to be an underground cartoonist like Robert Crumb—my favorite artist. I was so amazed by his work. I just knew from the get-go that I’d never be able to draw as well as him, so I had to draw differently. I knew you had to set yourself apart, which is why I started doing the stipple work.

How did you come to that style in the first place?

It kind of evolved. I was never a fan of that style of art. You know, besides Georges Seurat, I can’t even name any artists who do it. I just kind of fell into it. The good thing about that style for me was that it slowed me down, cause I had been drawing way too fast. Just not taking my time. Cause it took forever—that style was painstaking. I don’t recommend it to anybody! I couldn’t take assignments, because I couldn’t meet a deadline. But it gave me the look I wanted early on—more realistic photo-detailed work.

It must have been scary for you to move away from it. You had a signature style.

It was a slow process. I did it little by little. In the late ’80s, after Spy magazine, it sort of opened up floodgates, and I started getting a lot of assignments. I didn’t want to turn down work. I wasn’t making any money doing comic strips for smaller publications, and all of a sudden I started getting calls from The New York Times and Entertainment Weekly. I had to truncate the style. I was already sick of it. Also, it was affecting my eyesight. Robert Crumb kind of warned me that it would, early on. He said, “I love your detail work, but down the road you should really think about your eyes.” A few of the old-timers were like, “Why are you wasting time doing that stipple?” Will Eisner used to complain about it. A few other guys, an editor at MAD. Finally, I agreed with them.

You mentioned that working for MAD was your childhood dream, which I’m sure was true for a lot of people.

I thought it was a dream that I could never achieve—impossible to work for MAD.

You visited the magazine as a kid, right? When William Gaines was there?

Yeah. My dad arranged it. Sometimes there are perks with having a dad with connections like that. I was about 13. He set it up for me to spend the afternoon up there. I hung out in Gaines’ office. He was very accessible and showed me stuff. He was great. I met the art department there. Sergio Aragonés, especially, was a really nice, nice person. He didn’t know who I was, but he spent a lot of time with me. Gave me a drawing. It was a good example of how an artist should be with a young twerp who’s excited to be in their presence. I met some artists over the years, and they’re not always like that. But Sergio was great.

When you were older, did you envision yourself doing comic books? Or did you always think you’d be doing commercial stuff for magazines?

The thing is, as I got older, I kept drawing faces. Obsessively. Basil Wolverton–style faces, some more realistic. I was just obsessed with faces, obsessed with people. Like, I’m gonna draw you at some point. I was a fairly quiet kid, interested in absorbing. You know, it was hard to compete with my dad—especially socially, going out. He basically held court. I suppose my brothers and I were in the audience. My dad would always say, “Drew notices people that nobody else would notice.” I’d go to a comic convention, but I was staring at the comic book dealers. Or elevator men. My brothers and I became obsessed with our elevator men at our building on Central Park West. We knew all their names, had histories for them we’d invent.

One of the most interesting illustrations in your book Too Soon? was originally drawn for Field & Stream, a hunting magazine. It shows two brutish hillbillies yelling at each other, while a deer stands peacefully behind them, making eye contact with the reader.

It’s one of these cases where an assignment came in that I was all wrong for. The art director, who I had known at another magazine and liked, called me and asked if I would do an assignment for Field & Stream. I said, “Well, is that a magazine about fields and streams?” She said, “No, it’s hunting and fishing.” Well, I’m Jewish, I’m a vegetarian, I hate hunters. But I welcome a challenge, so I took it on. This was for an earlier assignment, and more assignments kept coming in. Sure enough, I became a regular for a couple of months at Field & Stream. And it was driving me crazy, cause I was feeling so guilty about being in this hunting magazine. Finally, they had this article about deer hunters. So I drew these hunters and tried to make them the stupidest looking people I could imagine. Idiots arguing with each other, while the deer looks at the reader confused. I tried to make the deer look as heroic as possible. They ran it. But they stopped calling.

You’ve also done work for Weekly Standard, a Republican publication. When you get called for this work, do you think, How can I subvert this?

Exactly. Well…it’s not subversion. Weekly Standard is a right-wing publication, a William Kristol publication. They never asked me to editorialize. I was basically doing caricatures for them, likenesses of political people. Whether it was a Democrat or a Republican, they never said, “Draw this person in a particular way.” It was always up to me. The editor, William Kristol, had a good sense of humor—go figure. At the same time, I was also doing work for New Republic, so I was able to bounce back to a liberal publication. I would never take an assignment to do a cigarette ad. A few things, I wouldn’t do. And sometimes I simply go too far. I drew Harvey Weinstein, the producer, for New York Observer. I looked at it and thought, I really went too far this time. Look at that face. He’s probably a really sweet guy. Why did I draw him like this? What is the matter with me? And sure enough—he bought the artwork. That’s happened before.

That’s how you met Howard Stern, right?

I did a drawing of him like 20 years ago for a trade publication, Radio & Records. They had been hard on him, dismissive of him as a radio personality. He was so tickled to be in Radio & Records with this amusing drawing by me, whose work he knew, that he called me out of the blue, almost like an excited fan. One thing led to another, where he invited me to illustrate his books. It’s like Jerry Lewis, in that he’ll call and talk about what I do. He never talks about what he does. He’s been very nice and supportive over the years. He’s gone on record saying that I’m his favorite artist—which I accept. A couple years ago, he was trying to do an animated TV show called Howard Stern: The Teenage Years. It was gonna be similar to the Chris Rock show. He asked me to design his family.

That would have been a fantastic show.

It was gonna be on FX. I don’t know what happened with it. I did a lot of rough drawings. I still have them—I’m gonna publish them at some point. That was when I was working with him the most, back and forth on that. He’s very easy to work with, very sweet.

Of all the publications you work with, what comes closest to your own sensibility?

Over the years, I think it’s been The New York Observer. I’ve done covers for them for the past 15 years—almost 200. I got so comfortable working with them that the editor would just call me on Friday, tell me what the story choices were, and not require to see a sketch or even necessarily know which story I was gonna pick. It’s a dream assignment. It’s a little different now. They have editors up there who like to interject their two cents—which is fine. In most cases, if it’s an editorial assignment, I like it if they tell me what they want. I don’t like doing guess work, especially if it’s a publication I haven’t done too much work for.

Do you still draw for MAD?

Occasionally. Their rates have gone down a bit, so I think they’re a little shy about hiring me. On occasion, I’ll do some work for them.

When you did covers for them, how exact did Alfred E. Neuman have to be to their template? No matter who draws him, it doesn’t seem to change much.

If you agree to do a cover of MAD—I’ve done about nine—you have to keep that in mind. When you draw the Alfred E. Neuman, you have to take the Norman Mingo template. Which is fine. I love drawing that face. A couple artists over the years have twisted it a little bit. Jack Davis draws it in his own style—it looks like a Jack Davis version of Alfred E. Neuman. The one time I was able to stretch it was when I did a cover of Alfred E. Neuman’s girlfriend, Moxie.

Who?

In the ’60s, they had invented a girlfriend for Alfred. She was on two covers of the magazine, one back cover, and then they retired her. The problem was—this is my theory—she looked exactly like Alfred E. Neuman, except she had all her teeth and a head of hair. So it was supposed to be Alfred E. Neuman’s girlfriend, but meanwhile, it looked just like his twin sister. It’s a little off. They brought her back briefly ten years ago for a special, and I did the cover. I updated her with Britney Spears hair. That was the one time I was able to take the Alfred face and twist it around.

I heard that Gilbert Gottfried—who wrote a very funny blurb for your new book—used to show up at MAD every month to get a free magazine.

It’s quite possible—he’s the cheapest man who ever lived. He did that with National Lampoon. I guess that’s where I met him, originally. We used to hang out back in the East Village, when we were younger. He’s a great comedian, but very hard to get to know. He’s very shy. He has to close his eyes when he’s performing, cause he’s so intensely shy. But then he can say anything. The most vile, disgusting things! He used to stop by my apartment in the East Village just to watch Lon Chaney Jr. movies. I’d be working.

You’d just sit there and work while he watched the movie?

Well, sometimes I’d watch, too. But he’d come unannounced. See, I had a VCR. I don’t think he had a VCR—too expensive. I had a lot of this stuff on tape back then, the mid-’80s. He’d just come by unannounced and ask to watch some Tor Johnson. So we’d pop a tape in. Finally, I stopped letting him in. Now Gilbert’s married. The last guy you would ever expect to be married with kids.

Everybody who works in magazines and newspapers has taken a hit lately. What’s it been like for you?

The magazine work has really petered out the last couple years. Some illustrators I know go on record saying, “Things are dead.” I’m more fortunate, cause I branched out to do these books and my own projects rather than wait by the phone for magazine assignments. I still have regular assignments that come in, and I still try to pick and choose. But things aren’t like they were 5, 10 or 15 years ago. I occasionally get e-mails from young people saying, “How do you get started?” I say, “I wouldn’t get into it if I were you—think of something else to do.”

Do you feel like you’ll concentrate increasingly on books?

Books and other projects. I’m working on a longer comic strip about Robert Crumb for a book coming out next year. They’re matching up cartoonists to do the life stories of famous cartoonists of the past. It’s eight pages, which is a lot for me, cause it’s gonna be mostly color. Monte Beauchamp, who designed the Jewish Comedian books, is editing it. He asked me to do Crumb. I told him that Robert Crumb’s life story has been told by Robert Crumb, over and over. Every detail of his life is chronicled in his own comics. How can I do a biography of Robert Crumb without repeating every detail? The only way I can do it is from my perspective. My piece is called “Robert Crumb and Me.” It’s basically my perspective, approaching Crumb as a fan of his work and then finally doing work for his publication Weirdo. By no means am I a good friend of his, but I’ve had a lot of encounters with him over the years. He’s been very supportive of my work. If I get back into doing comics, I think they’re going to be more of a personal nature, rather than show business parodies.

Early in your career, you drew people from the fringes of show business. Then you went onto draw famous people for Entertainment Weekly and the Observer. Do you feel like you’ve come full circle?

I don’t know if it’s a full circle, so much as bouncing back and forth. When I was working on the Old Jewish Comedian books, I was working on assignments for Entertainment Weekly during the day, like Jennifer Aniston or Friends. Well—I finally installed a “No Friends” policy, cause I got sick of drawing them. A show I’ve never seen! But I couldn’t wait to get back to the Jewish comedians. It was cathartic for me. My next book is possibly going to be of famous cartoonist faces, portraits. And my last book was Sideshow Freaks. So I don’t know when the circle ends. It’s just sort of bouncing around again to whatever tickles my fancy.