This interview was conducted in 1970 by Bill G. Wilson, Duffy Vohland, and me. The three of us were obsessive comics fans and had become good pals due to our active involvement in fandom. Bill edited and published a fanzine called The Collector; Duffy wrote a column for the fanzine Etcetera; and I published several ’zines. Bill and I were both 15 years old; Duffy was a little older, having just turned 18. I don’t remember how, but we corralled Joe Sinnott into an interview during Phil Seuling’s New York Comic Art Convention, held over the July 4th holiday weekend, but he was kind enough to take us back to his room at the Statler Hilton Hotel where we sat down and set up our tape recorder. Although this recollection is somewhat revisionist, Sinnott was certainly among my favorite inkers at the time, and a favorite inker was a very important critical judgment to make — at the time. In retrospect, his line may be a little too slick, too clean, too perfect, but his run inking Kirby on the Fantastic Four — if Kirby had to be inked by someone other than Kirby — was certainly a professional accomplishment he could take pride in. I frankly don’t remember him inking other artists except John Buscema, and he seems utterly ill-suited to ink Neal Adams, who he mentions here, but his inking of Kirby was wonderful.

My memory of Joe was that he was incredibly gracious, warm-hearted, and patient. I kept in touch with him for several years, maintaining a casual correspondence, during which he put up with my incessant questions and requests. He subsequently inked several pencil drawings for me that I had acquired by other contemporary artists (such as Steranko) purely as a favor to a fan — never asking for payment.

Re-reading this interview, I am struck by how Sinnott elevated our mostly dopey questions by never talking down to us — this group of teenagers sitting in his hotel room — and reflecting on his career and expounding extemporaneous, observant critical judgments about the work of various artists as if he were talking to peers. I probably hadn’t re-read this until now — that is, in 50 years — and was particularly taken by his answers to two questions.

In answer to my question, “Do you think the comic book as we know it will be around ten or 15 years from now” — the death of comic books was always being anticipated, it seems — he talks about how he hopes comics can evolve from their predominantly adolescent content: “They have to improve but they’ll still be around in the same form that they are today, but there may be a different type of comic for a different segment of the population: for the older people, which will come to be too…a more realistic type of book which I’m looking for.” Prodded by a follow-up question by Duffy Vohland, “Do you think ACBA will do a lot to raise the literary content of the comic book?,” he replies, “They seem to be quite determined in their goals and I was surprised by this…but they do seem hell bent on attaining those goals.” The “goals” he’s referring to here are raising “the literary content of the comic book,” and however you interpret that, it clearly speaks to a yearning on his part to be a part of something more…adult in conception. The Academy of Comic Book Arts, when it faced a fork in the road early in its existence, chose to become a social organization rather than an activist one and it is unlikely at any rate that such an organization could ever have successfully pushed for a change in the mindset of editors, publishers — and readers. Nonetheless, it’s historically significant to consider that even a workaday journeyman like Joe Sinnott thought about this question as early as 1970, however rudimentary those thoughts may have been.

His answer to my last question is a sobering reflection on the human ramifications of precisely that issue: the meaning and content to which he devoted his professional life. To my embarrassingly generic and innocuous question, “Could you give any aspiring artists tips about…breaking into the business,” Joe’s answer was more thoughtful than I had any right to expect. He begins by answering the question literally — giving tips; he could have left it at that, but then he segues into a pensive, unself-pitying mode and talks about his own personal misgivings, not about cartooning or comics per se, but about his options as a working cartoonist — inking Marvel comics, which he refers to twice as a grind, as well as a bore, and the system itself as “an assembly line production, which is what it really is.” He was right about that, of course. “I think I honestly least enjoy doing comics that I’m doing for Marvel. That’s what it amounts to, Gary,” he says with such a complete lack of guile or evasion that it takes your breath away by its sheer naked honesty. I remember being somewhat shaken by this at the time — no one had spoken about the hard reality of producing those comics I loved in this way. Little did I know at the time that the sentiments he expressed here served as a synecdoche for the frustration (and sometimes rage) against the system that many artists felt at that time — Wally Wood and Gil Kane, for example. A dose of cold reality, from 50 years ago.

Gary Groth,

July 6, 2020

.

GARY GROTH: When did you first become interested in drawing?

JOE SINNOTT: As early as I can remember — we had school teachers as boarders in our house. We had like a rooming house, and one of the teachers brought me — I can still remember it — a large box of crayons. I must have been about 3 years old. It had a big Indian on the box cover. I must have drawn that Indian till I knew it by heart. I did it so often, with crayons she gave me. That may have been the start of how I got interested in drawing. We also had this fellow who worked in a diner as a border. He was from Germany. I think he was on a submarine in the first World War. He would come home maybe six o’clock at night and sit in the living room. I was about 7 at the time. He had these white pants on, so at the end of the day, he would draw all over his pants with a soft pencil! [Laughter.] He would draw — Indians, soldiers, y’know. And at that time I thought he was terrific. He stayed with us for about five years, and every night he would draw all over his white pants, all kinds of characters, even Western characters though he was from Germany. Even though he was a boarder I used to play with him, he was just like a dad to me. When he moved away I really cried like a baby. I missed him. He put me on the road to drawing, I think.

But then again, I copied from Smilin’ Jack when I was a kid. This was one of my favorite strips. And a little later on, Alex Raymond. I was crazy about the early Caniff. I still think the old Terry, '34 to '37 before he got too realistic, had so much charm that that’s what’s missing in comics today. You remember — the button eyes and so on. There’s a little bit of it today in Treasure Chest, in Chuck White. It’s a little realistic but has some of the old Caniff flavor. I thought there was a lot of charm to that. There was a lot of caricature to the characters, particularly Terry and Connie. But there was a lot of action. But then again, it might have been the age. I was about 8 at the time that Terry came out. You couldn’t wait for the next day; it was such an adventure to wait! But maybe it’s because today you’ve seen it a hundred times or a thousand times and it’s not novel anymore. But in those days it was really an adventure to wait from day to day to see these strips come out because they were new and nothing like it had been seen before. And the same with Flash Gordon. You couldn’t wait from Sunday to Sunday. It was like waiting for the Saturday serials, only the Sunday strips were just as exciting as the serials. The middle ’30s were great for kids and comics.

GROTH: Could you give us some background information on yourself?

Well, I lived in Saugerties [N.Y.] till I was about 12 years old, and then moved about five miles away to a little farm. I hated to move because I lived right in the heart of town. I was interested in sports and I was on them — well, we didn’t have a little league in those days, but we had our teams. I just hated to move away from all my friends at that age, and where I moved to, was a farm where you couldn’t see your next-door neighbor. And the only way I could get into town was to hitchhike. But once I got used to the farm I really enjoyed farm living. It was a small farm, but it was a lot of fun. When I was in high school I played on the baseball team and soccer team. It was a small school, there were only about 500 kids in it. Now there’s around 2500 because IBM has moved into the area; it’s really grown. The old days were nice.

Well, I was in the service from '44 to '46, in the Navy with the Seabees, and drove a truck. In fact, I never drove a car when I was home; I didn’t know how to drive a car. But anyway, we went to Okinawa and after the war, I went to work for a cement mill upstate when I live. My father was a packhouse foreman for 40 years up there in the plant. I knew I wanted to be an artist — a cartoonist of some kind eventually, but I was enjoying playing ball, etc. and I just wasn’t interested in going to school at the time; I was out of high school. But then I got tired of working. I was working at a lime quarry and it was 30° below zero at times during the winter. It was pretty rough, so I looked through the papers and I saw the Cartoonist’s & Illustrator’s School advertised, which was on West 89th at the time. So I came down here in ’49 or ’50 and that’s when I started my art schooling.

GROTH: Before you started school there, did you read comics back in your youth?

Oh yeah, very much. I used to have to walk two miles to the general store which sold comics. They had every type of comic there. The big comics those days — it’s funny, the Marvel comics didn’t really appeal to me then. I enjoyed Hawkman because it looked so much like Alex Raymond’s work. I’m sure the guy copied a lot of Raymond’s figures. That appealed to me, though I never knew who did it. I don’t believe he ever signed his name.

And The Batman was one of my favorites. I was never very enthused with Superman, but Batman always impressed me. But Hawkman — the artwork for that time was great. I can’t remember one Hawkman story but the artwork impressed me very much. And I always used to like Congo Bill in Action Comics for some reason. I would buy Action Comics just for the Congo Bill story, not for Superman. Maybe it was because it looked something like Jungle Jim which I liked. Superman never really impressed me, although I did like Jack Kirby’s Boy Commandos a little later during the war. It must have been about ‘43 or ‘44. Do you remember the Boy Commandos?

GROTH: I don’t have any of the original comics, but I’ve read a few of their stories from friends’ copies.

Oh, that was tremendous. He had these little characters; one with a derby hat, etc. They were kids and fought the war in Germany. They were called the Boy Commandos. They were terrific. You remember them, Bill?

BILL WILSON: Yeah. I have a very small collection of them.

They were very good.

GROTH: Did Kirby do all the artwork on the series?

Yes, [Joe] Simon did the inking, however. That’s the first Kirby work that I was aware of. You should look downstairs, there may be some floating around. You’d really be impressed by that. It looked very much like the stuff Kirby does today, But it was a funny thing. I don’t remember Kirby doing Captain America at all. I just don’t remember buying a Captain America book. It’s funny — a dime was a lot of money in those days, but somehow I always got every Action Comic that came out. And Hawkman too. Hawkman must have been in another book; he couldn’t have had his own book, I don’t think at that time. Well, I know where I got the money. I used to sell junk every Saturday. Like old rubber tires and scraps of brass; anything I could find. Every Saturday the junk dealer would come through ringing his bell. He had this old truck, and he would weigh your stuff. He would give you ten, fifteen cents. First thing you know you’re down in the store buying comic books. You never missed the books. You’d buy them faithfully.

GROTH: Do you still have all of those old books?

I wish I did. I don’t know what happened to them. Just like some of the books you probably had when you were younger. You threw them away or something.

GROTH: How did you begin your career as an illustrator?

Well, like I said, I was going to the Cartoonist’s & Illustrator’s School. When I went down there I really wanted to be a sports cartoonist or go into advertising. I really wasn’t interested in doing comic-book work, or comic-strip work. However, I would copy Caniff and Raymond, but I really didn’t want to do a strip.

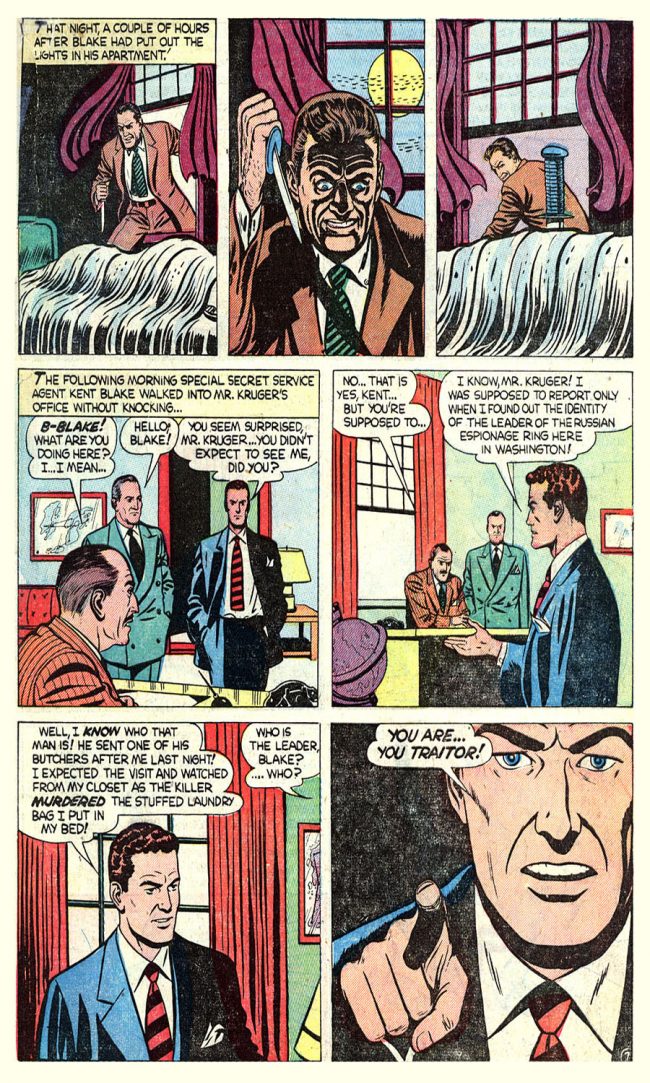

But, anyway, after the foundation class and I went into the Cartoonists class, Tom Gill saw my work; he was one of the instructors down there, though he wasn’t my instructor at the time. He was doing work for Dell and Marvel, Dell, in those days, did a lot of books on the films, like Union Pacific, etc. Tom asked me if I was interested in working on his books, He had this little studio in Rockville Center and there was another fellow who worked for him from C&I; he wasn’t in my class though. His name was Norman Steinberg, very good at horses. We would go out there on Saturdays and Tom had a closed-in porch, it was like a sun porch, and made it into a studio, Norman would pencil the Westerns and I would ink them and Tom would put the heads on the characters to make it look like his work. Tom was a prodigious worker. He would teach all day in the school, and he would draw all night for the comics; till 10, 12, 1 o’clock in the morning. I don’t know how he did it. In fact, I was talking to him last night. He was here. First time I’ve seen him in 15 years. He’s taught a lot of fellows down at the school. But anyway then we got the Red Warrior book to work on from Marvel, and also Kent Blake. We passed it around; some would do the penciling, some would do the inking. Y’know I’d do five pages of penciling, another fellow might do another five pages. Tom would do all the heads, so it would all look like the same person had done it, and surprisingly it did! Then after a while, I was doing everything on the Kent Blake strip. Tom had asked me to do everything. The penciling for Kent Blake and the inking. I did that for about six months to a year. I was still at school, and it was pretty difficult because I was doing it at night and Saturdays. And to add to the chaos, I got married at this time.

So then one day, I thought that I’d take some of my samples and I’d go over to Marvel and see if I could pick anything up. But before that, I had a job for St. John’s; I was in school for about six months and I thought, “Boy, my stuff is terrific! I’ll start making the rounds.” [Laughter.] Someone told me about St. John’s Publishing Company, so I went down there and they gave me a five-page filler for a Mopsy comic book called “Trudy,” and I did that and never heard from them again (my first bubble burst). It wasn’t bad — I thought it was terrific for that period, but anyway, back to Marvel. Stan wanted to see how I could pencil it. He gave it to me the day before school went on vacation. I went home and I brought the penciling job back after vacation; it was two weeks before Stan saw the pencils. And it was only one page, so he was probably wondering what in the world happened to it. Anyway, I brought it in and he seemed to like it — a little bit. So he gave me a story to do. It was a five-page story for a Kent Blake book that Tom Gill was still doing, but this was a five-page filler story. So, after that, every time I would complete a story, Stan would give me another one. But that was at a time (1951) when comics were really hitting it big and there were more scripts than artists. Anyone could really get a job in comics if they could do anything half-way decently, at least it appeared that way.

So, that’s how I got started. And I really didn’t work for anyone else until things got slow in '57. Everything I did was for Marvel (Timely), and there wasn’t a week that I didn’t have a script or two to work on for them. Of course, they were all kinds; war, Western, science fiction, and of course, ‘52 and ‘53 when they had the big horror craze; before the Code came along. It was a great period to be in comics — I enjoyed the variety.

GROTH: Were there any comic book artists back then who inspired you?

Yeah! I liked Reed Crandall’s work. And I liked [John] Severin’s work even back when he was with First Prize Comics; he used to do these Westerns. He had an Indian character, I forget who it was, but I used to buy those books. I still have them, in fact. He was penciling, but Bill Elder was inking it. Severin has always impressed me. In fact, Stan Lee, I think, was always tremendously impressed by Severin’s work. He was pretty happy when John came over to Marvel to work. But some of the guys that worked for EC in those days, even Wally Wood, who was quite young, and just out of school, he was just a little bit before me at C&I, but he did some great work for EC. I’m sure they didn’t get paid much in those days, but they really knocked themselves out, I thought. Al Williamson did nice stuff for them; much cruder than he does today, but still excellent. They were all good.

But Marvel — Russ Heath did some nice work in the ’50s for Marvel. But Kirby wasn’t there at the time. Do you remember Russ Heath? He does work for DC now. He did terrific war books and horror books. But there were so many guys that worked for Marvel that aren’t in comics today, that were fairly good. I’ll tell you who was very good. I never see his work anymore; someone told me he worked for Caniff, but I really can’t be sure. His name is [Fred] Kida. Are you familiar with his work?

GROTH: No.

His work is very similar to Frank Robbins’, who is similar to Caniff in their style. But I really enjoyed his work. His work is like Caniff’s, his slashes, his wrinkles, his heavy blacks, etc. His mystery stories were really good. Stan Lee was really impressed by Kida’s work. If he wanted to show you someone’s work to have you get inspiration from, it was usually Kida’s work. He’d say, “This is what I like.” Stan, not that he would want you to copy someone’s work, but he would always show someone else’s work to another artist. In other words, if he wanted my work to be improved upon, he would show me another artist’s work, like Kida’s.

Another guy who used to impress me, he came later at Marvel, but during the slow period during '57 to '60 before the superheroes really made their comeback, was Don Heck. He did an awful lot of work for Marvel. And his science-fiction stories, I thought, were on a par with anyone’s. Even EC’s good period when Williamson and Wood were doing their science fiction. Don Heck had a nice style, and his backgrounds were fantastic. They were terrific; his futuristic cities, they were tremendous. I was very impressed with his work. Although I can’t understand why he doesn’t appear to do much artwork today. At that period, when things were bad, he was in every Marvel book it seemed, although Marvel didn’t have too many books. He really carried Marvel through that black period. Another great over at Marvel was the late Joe Maneely — a real favorite of us all.

GROTH: What “bad period” was this?

Fifty-seven and things were going quite slow for Marvel. The Comics Code had killed the horror trend around ‘54 and that was the big trend in that period. So, Marvel and all the other companies had to go back to the old standard; Westerns, war, which wasn’t big anymore because the Korean War was over, and the romance, which had always held its own. Science fiction. Science fiction held its own also. Horror was the big thing in the early ‘50ss. The Comics Code killed it.

I remember, in fact, it was Martin who was telling me, this friend of yours, and I didn’t realize it at the time, but he said that when the Comics Code came into being, they held up a drawing; it was a picture by the Associated Press and one of the photo services. The Comics Code administrator was showing the change the comics commission had made in a drawing for a horror comic to meet their requirements. They showed what their changes were. And the drawing they held up was one that I had done called “Sarah.’” And I remembered when I did it. This must have been around ‘56, and I remember when the book came out; everything was changed. The heads were all changed. There were no more ghastly expressions. You couldn’t show a mean expression, you couldn’t show speed lines, or even have a sound effect like SPLATT! They really went too far in their restrictions. I would like to see the original drawing, though. I would like to compare it with the Code’s pic. Although I do have the comic book and they did make many corrections.

For that period, there were a lot of comics, I think you’ll agree, that were pretty deplorable. The ones that I was doing for Marvel — you didn’t take them seriously. You didn’t realize kids were reading these and taking them seriously. But you couldn’t see the harm in them. I couldn’t anyway. They were fun, very much fun to do. Every story was different to a degree. It was fun — you could use your imagination and it was just a fun thing to do. But you didn’t realize that you might be affecting these kids. They might have been; it might have affected these little kids, although I really don’t see how they could have. Marvel’s books weren’t as bad as the smaller companies’. I can’t think of their names right now, but there were some that were quite sexy for the ’50s, and really quite bloodthirsty. EC had some that were pretty horrible, but they were done so well, in other words, the art was so good and the stories were so interesting, that you didn’t mind the gore. The endings had a slight moral to them. The other books (by the smaller companies) had no meaning to the stories, so the gore is what came through, and that made them very undesirable I think. They were the ones that needed to be tempered down.

VOHLAND: Do you think it would be a good idea for the Code to be revised?

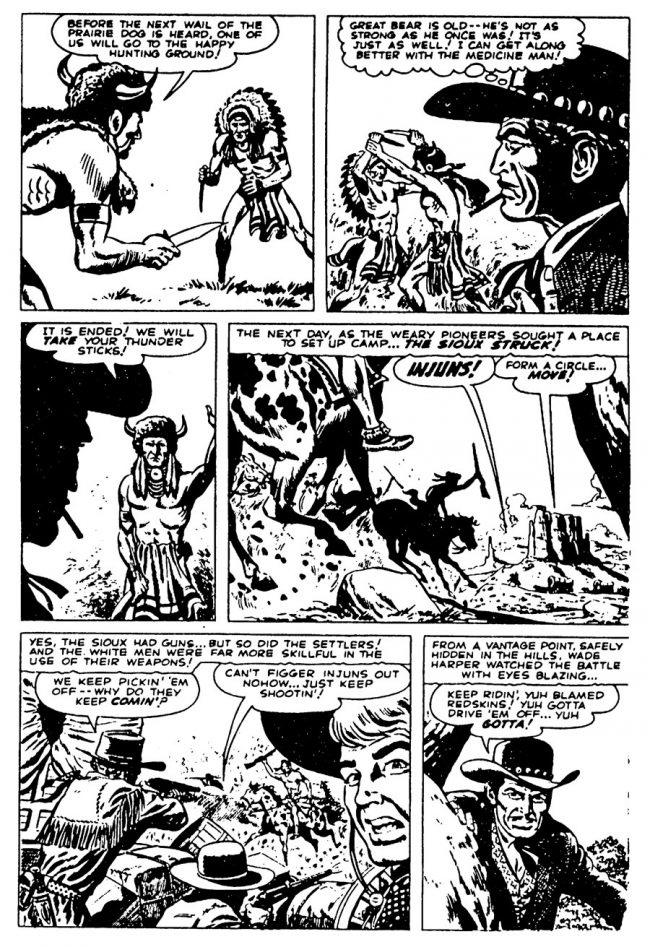

They had a very big discussion about that yesterday afternoon down at the [ACBA, the Academy of Comic Book Arts, a professional organzation] meeting. Gil Kane made a very good point. He doesn’t think it should be eliminated. But he felt there should be an open end to one end of the Code, to speak. In other words, give the artists and writers just a little bit more room to maneuver, to appeal to a different taste. Although the Code is a little bit liberalized than it used to be, I’m sure you’ll agree with that. I did an Indian story one time when the Code first came into being. It was called “When the Sioux Strike!” Anyway, two Indians were fighting to determine who was going to be the leader of the tribe. They had knives, which you’ve seen in the movies, and which you’ve seen in real life. I didn’t show one Indian killing the other one; they were just wrestling. One held the other Indian’s arm over his head like this [showing the movement and stance of the Indian on Groth]. In the last panel, the Indian had his knife down at his side. He was speaking to the guy who was running guns for the Indians. Anyway, when the revisions were made, they took the knives out of their hands. So, what you saw, were two Indians like this [again, showing us the stance as “corrected” by the Code], one looking at the other, then they were wrestling with one another, and last, the guy had his hand down at his arm down by his knee. And you wondered what happened to the other Indian! You didn’t see it, but in the original story, you knew he was dead by the knife. In the revised story, you didn’t know what happened to him. In other words, they just went a little too far.

VOHLAND: Do you think ACEA could get some changes made in the Code?

I don’t think they could. The Code was very adamant yesterday about making any changes at all. Stan Lee asked them if they were working on more liberalized viewpoint of the Code, and the representative from the Code wouldn’t commit himself at all. But I really think they’ll liberalize it a little bit. But as far as having an open-end policy as Gil Kane suggested — to give the artist and writer real freedom that they would like, I don’t think that will come to be. Not yet. Although it would be nice. In other words, to have books that would appeal to a more serious buyer. I really don’t think it’s going to happen.

VOHLAND: Do you think that if the Code were liberalized too much, some companies would go overboard on the sex, gore, etc.?

Yes. I don’t think there’s any question about that. I don’t think it would last too long. It would clamp down in some respects, on something like that. In other words, they wouldn’t allow it to go on for any length of time.

WILSON: What do you think of a comic book published outside the jurisdiction of the Code?

Are there any that aren’t approved by the Comics Code today?

GROTH: I don’t think the Dell books were.

They didn’t have the Code seal? They were censored by their own administrators, right? The Code doesn’t trust the individual companies as far as censoring themselves, and I think the companies learned a lesson as far as their ‘54 period restrictions put on them by the Code. I’m sure they know enough from prior experience, what should or should not be censored. I’m sure they could eliminate the Code entirely, and the individual comic companies, the big ones, not the ones that would capitalize on not having a Comics Code, could censor their own material to a degree where the parents could find no fault. Don’t you agree with that? I really do. I don’t think there’s a need for the Code.

GROTH: The problem is the distributors. They won’t distribute what doesn’t have the Code Seal implanted on the covers.

That’s true. The Code means something to the distributors. I’m sure they don’t even know what’s inside the books, but they see the seal there, and that means everything to them. That’s a point. The trouble is, comics were meant for kids when they originated, and no matter what the content of them today is, even though it’s geared for a more adult audience, the distributor still thinks it’s a kids book, 7-8-9-10-year-old book, and they have no idea what’s inside. You have to agree, the EC books were far ahead of the 8-9-10-year-old kid. The Ray Bradbury stories were pretty mature, and obviously over the head of the younger readers.

GROTH: To get back to questions about you, was your first professional work done in comics, or was it in another art medium?

Well, the first job I was ever paid for was a fast drawing I did of an Army officer during the early part of the war. I was about 15 years old, and I was given 15 dollars for it. But the first job I was paid for in comics was a five-page filler for a Mopsy comic book for the Saint John’s Publishing Company called “Trudy.” I forget what the rate was back then, but it wasn’t bad. This was in 1949 while I was attending C&I. But the first big account I had was with Marvel in 1950 with Tom Gill, and the reason, I’ll answer your next question, Gary, the reason I went to Marvel was because I was familiar with their books, working on them with Tom, as he had a Marvel account. He had Red Warrior and Kent Blake and I was penciling and inking Kent Blake, and also helping on the Red Warrior. So when I felt I was ready to go out on my own, I went to Marvel because I knew their books and I felt, well, Marvel was big and they had a lot of scripts that were available. So I did quite a bit of work from that year, 1950 until 1957 when they had such a backlog of books finished that they suspended operations as far as giving out scripts and buying art. I guess they could carry along for, gee, about six months to a year on the books they had already completed; at least that’s the impression I got.

GROTH: To change the subject for a minute, have you ever painted anything?

No, I’ve worked a little bit in colored inks, but never painted in oils or tempera or anything like that, I’ve done a lot of wash in advertising art that I’ve done. In fact, I enjoy doing fashion work very much and I also enjoy doing sports cartoons, but I’ve never really done any work in color before. I still do colored crossword cover magazines, but these are done with acetate overlays.

GROTH: Are there any painters today that you particularly enjoy?

I’ve always liked Norman Rockwell because I believe he’s basically a cartoonist, but also because his work is technically amazing. As for his storytelling, they’ve got such a human interest story behind them. He’s done some terrific things, “The Homecoming Solidier [G.I.].” One of the best that I feel he ever did was this “Homecoming Marine,” I think it was called, The marine was sitting in this garage telling of his exploits during the war and it’s a beauty to behold. It was a first-place winner in a Society of Illustrators exhibit. He’s done so many, in fact, I used to cut out his covers and save them. But I also like Tom Lovell. He does terrific seascapes and he’s an adventure type illustrator. I also like Albert Dorne’s cartoon type of illustration. And with the western artists, as I mentioned before, I like the old-timers like Remington and Russell. I also like Fred Lutiken’s stuff, who’s contemporary.

GROTH: Well, I’ve always asked the artists I’ve interviewed if they could explain a little about the technique they use in their work, and all of them have difficulty in answering this beca —

Well, that’s a hard word to define, technique. In fact, I think every artist answers it in that way, really because when you say technique, I think you mean, do I use a smooth style, rough style, heavy blacks, fine lines, thick lines, you know. I think that’s what you mean by technique, right?

GROTH: Right, right.

Well, when I do the superheroes, I try to keep it slick and smooth, because that’s the way the superhero age is supposed to be. You know, modern, everything clear-cut, metallic, and glossy. But if I was doing a Western, I would try to keep it rough, as the subject matter is rough, with buckskin, dirt, and rocks, etc. I’m conscious of what type of story I’m inking. Like when I worked for Treasure Chest; if it’s a sea story or a war story or a biographical thing, there isn’t much of a change in the inking, but it’s there and you can make it out.

GROTH: Do you use any special or different techniques when you ink different artists’ work?

I don’t think so. Some artists pencil with a feathering type of pencil line, it’s like a sketchy line and you have a tendency of feathering a little bit too much on them, which I don’t feel is too good. I used to feather an awful lot and I’ve been trying to break away from it, but it seems to be the thing to do. I’ve seen some real good, sharp things that were presented to different companies and they were turned down. They felt that they wouldn’t go over. The work contained sharp blacks and whites which I really liked, but I don’t know. I guess that some people don’t feel that’s the way to work some of these books.

GROTH: Doesn’t Vince Colletta use a lot of those short lines, real scratchy lines?

Right, right. Vince can do some terrific inking when he wants to, but I don’t like the way he puts the fine lines in the muscles. I feel he uses too many lines. I may do the same thing occasionally, but I don’t like it. I like the solids and I think it makes it like Frank Giacoia’s inking. He feathers occasionally, but his lines are so bold and clean, and sharp and crisp. That’s the way I like them.

GROTH: Frank Giacoia’s inks are very similar to yours, aren’t they?

He did a book one time, an annual of the Fantastic Four and I thought for sure it was my book. I looked through the whole book and I would have sworn up and down it was mine until something hit me. I think it was that he didn’t have a couple of little dots where I occasionally put them on stones, and I suddenly realized that it must’ve been Frank’s work. But, I was really surprised. I thought sure that I did it. I think our styles are a bit similar, but I think his is a little bolder than mine. His lines have a little more force to them.

GROTH: Do you change the artist’s pencils much in the inks, say, in the case of John Buscema, who’s very tight, or in the case of Neal Adams, who I hear is very loose?

It’s hard to say. People say that Neal is loose, but in the two stories that I’ve worked on, Thor, they were quite tight, although the middle and backgrounds were loose on occasion. It started out quite loose and in the middle he seemed to get the feel of the book and from there on, it was a breeze to ink. I was telling someone yesterday — I don’t know if I told you, Gary, but the pencils were so beautiful in spots, they were hard to believe. I thought Buscema’s pencils were so beautiful, but parts of the Adams story were so really tremendous I thought Buscema had a hand in it. But I would rather ink Buscema than Adams because John seems more consistent. Neal, it seems, has so many irons in the fire, that sometimes it appears as though he’s rushing a little bit and other days when he may not have too much to do, he’s the equal of anyone. But I would rather ink Buscema’s work because you know that every page is going to be consistently excellent.

GROTH: You penciled several of the early Thors, didn’t you?

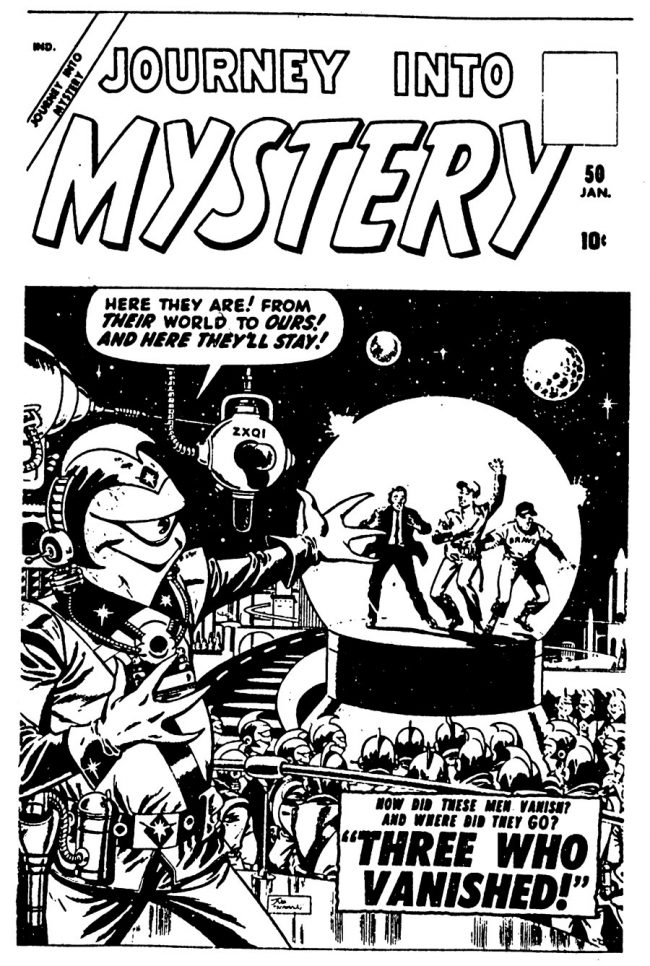

There must have been four or five, at least four. I can’t remember exactly. I know I did at least four.

GROTH: Well, how did you acquire that job and why did you stop penciling and relinquish the job to Kirby?

Well, actually, I inked the first Thor book. Kirby penciled the first Thor. You may have remembered. It was Journey into Mystery eighty-something. I think it was in the eighties [#83]. It was a three-part story and it was the introduction of Thor, and I thought it was a terrific character with great potential. I don’t know whether Stan or Jack created it, but anyway, I thought it was really going to be something. I don’t think I inked any more Thors until I started penciling it. At that time I was doing science fiction for Marvel. I don’t know if I did any war or not, but this was in the early ’60s. I think it was ‘61 or ‘62 if I remember correctly. So Stan just sent me Journey into Mystery #90, I don’t know, it might have been #89, and it happened to be a Thor so I penciled and inked a couple of the books, but I feel it was one of the worst things I’ve ever done because I just didn’t have the feel of the superhero type story. I just couldn’t handle it the way it should have been done.

GROTH: Does Stan keep you continually busy or does he limit your workload so you can do other things besides working on comics?

Years ago I feel he would have preferred that all his artists do as much work for Marvel as possible and not work on the outside. And I think an artist would rather do it this way because deadlines conflict and it’s quite a strain on the artist. But I have such a good account with Treasure Chest, and I’ve been with them for so long, that I wouldn’t give it up. I like to do their stories. They’re interesting to do, they’re varied, every one of them is different, y’know, they’re biographical — war stories, sea stories, science fiction. They’re just fun to do. Like in the old days with Marvel. But Stan has always asked me if I could fit in another strip here or there.

GROTH: Is Stan open to suggestions from you?

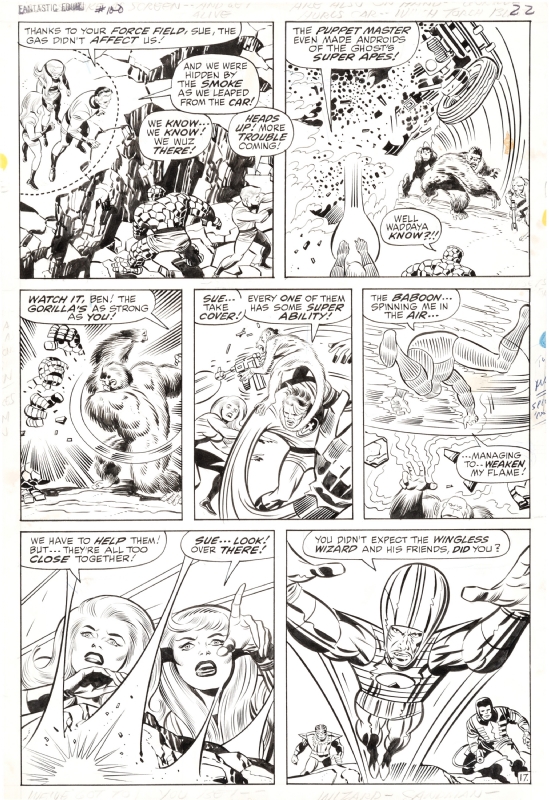

Yes, I think so. I really don’t remember ever suggesting anything to him. I know that when I started inking the FF, I was no stranger to Jack ‘s work, I inked Kirby in the past and I used to make changes here and there where I felt they could improve the work. Stan told me when I did the first couple of FF’s, I think it was issue 44, he said, “Joe, Kirby is so good, but if you see something you could improve, don’t be afraid to go ahead and do it.” And he’s never criticized anything I ‘ve ever done on Kirby’s work, although I do remember Sol asking me to make the Black Panther’s costume more black.

I know there’s a couple other stories I’d done with some of the other fellows where they’d, say, make the shoulders of the character a little bigger, etc., because certain artists have a tendency of making the muscles and everything, a little more natural and not how the superhero figure should be drawn. That has happened and I hope that the artist doesn’t feel that I’m making any changes on my own. But I don’t like to change the artist’s work too much, Gary, because every artist feels that the way he puts it down is the way it should be. Like I changed Kirby’s ears a little bit and his eyes on his girls just a little bit. Not much, just a little bit here and there. I ‘m sure Kirby never resented it, but I’m sure some artists might and I feel they have a right to. I’m sure I would. I did with the Kent Blake stories. I would draw the ears, in fact, I would draw the heads and Tom Gill would change them and they would look like his heads, which was right, really, because it was his strip.

GROTH: Who’s pencils have been the most difficult for you to ink?

Well, I only inked one of Don Heck’s stories, and I don’t know why — I forget the story now — it might have been Captain America. Yeah, I think it was Captain America and I had difficulty with it. I was really surprised that it was so loose. I’ve always been an admirer of Don Heck’s work. In fact, I feel his science-fiction work is on a par with anyone’s. I don’t think anyone could top his science fiction, not even Wally Wood or Al Williamson back in the EC days. But I was surprised at the change of style from his pencils to his inks. The pencils were very loose, much looser than I expected because his inks are so tight and complete. He might have been rushed on it. I don’t know if someone else had done the breakdowns on it, but I would certainly like to ink some of Don Heck’s science fiction. I didn’t enjoy doing Gil Kane’s Captain America. I don’t know why. Maybe because it was such a departure from Kirby, but I did have a little difficulty with it. I really don’t know why, but I didn’t like to ink that one. I guess you have to work with someone for a while before things begin to click.

GROTH: Do you know how the Code operates? Does the Code censor the pages before they get to you and have you make any needed corrections —

I’m not really too familiar with the Code, but I do know that the art changes are made after the artwork is finished. In fact, I don’t know if I talked to you earlier about the horror strip I did back in the early ’50s; this is the one story they used as an example to show how the Code was operating. In other words, the director of the commission, I think it was Murphy at the time, presented before the press and wire services, a picture of a panel I did from “Sarah,” a story I did for Stan. One picture showed how the panel was before the Code changed it, and the other pictured showed how it looked after the Code “corrected” it. It was a presentation to show how the commission and the Comics Code cleaned up the comics, so to speak. I have the book at home and I do remember that they changed all my heads. It was all quite ludicrous. That’s the only thing I’m aware of. I don’t know if there was any blood in that story, I really don’t remember.

Even at that period when they first started the Code, you couldn’t show speed lines, or “splat,” “pow,” etc. or someone hitting another person in the jaw. You couldn’t show speed lines of the “smack!” or the noise. If someone was shooting a gun, say a wagon train was being attacked by Indians, you couldn’t show the Indian falling in the same panel where the gun was being shot. You had to show the rifle in one panel and the Indian falling in the other, but you couldn’t show the actual shooting, which is a little ridiculous, I think.

I do feel the Code did clean up a lot of the small companies which were really exploiting the market with their sex and gore to a great extent. EC had a lot of gore, but their stories were so good that it over-shadowed the gore in their books.

GROTH: Well, they had such classical art by Wood, Williamson, Ingels.

That’s right. All those guys. Graham Ingels and George Evans, they were all good. Reed Crandall did some nice stuff for EC too. The horror, he was terrific at that, and his pirate classics were unsurpassed.

GROTH: Do you think the comic book as we know it will be around, say ten, fifteen years from now?

I really don’t see how there’s going to be much change. They’ll still have war to a small degree, they’ll have Western, romance — they’ve been around for thirty years now. They change very little really. The art, naturally, is improving all the time and so is the writing, but they’ll still be great strides made in the art and in the writing, which is only understandable because of the competition. It gets greater and greater every year. You’ve got to do better work than the next guy or at least do as well, but better than the year before. You can see the improvement all the time; even from the superheroes of today to those of just five, six years ago. The techniques are that much better and the artwork is more imaginative and the stories are better in many cases. They have to improve but they’ll still be around in the same form that they are today, but there may be a different type of comic for a different segment of the population; for the older people, which will come to be too, y ‘know a more realistic type of book which I’m looking forward to.

WILSON: I was wondering what type of comic strip you feel most comfortable with. Science fiction, war, superhero, romance, etc. What do you feel you do your best work in?

Well, what I feel I do the best on, Bill, is the straight illustrative-type stuff. Like I do for Treasure Chest, e.g., the stories on Pope John; the Kennedy and McArthur; and Eisenhower and all the other biographical things that I’ve done, the historical type story. The type that Reed Crandall is really famous for. I really enjoy this type, but I also enjoy doing light, humor type stuff, but I don’t have the opportunity very often.

It seems when someone wants me to work for them, they want me to do the realistic, illustrative-type strip. Maybe it’s because I put a lot into the backgrounds, much atmosphere. I put a lot of work into this type of strip. But my weakness is the superhero. That’s the one I feel weak on. I really enjoyed doing the old Westerns and the war and science fiction, etc. I felt I was quite capable at that. The Navy stories and the variety that Marvel offered. But the superheroes; I’m not a good figure man, at least not as good as I feel I should be. And with superheroes, that’s the one thing you have to be. A good figure man can compensate for a lot of weaknesses. I feel I can pick up anyone else’s work and no matter how good they are, I feel I can do justice to their pencils. And many times I feel that I can improve it a little bit. So, I think I’m really strong at improving another artist’s work.

VOHLAND: Do you think ACBA will do a lot to raise the literary content of the comic book?

Well, Duffy, they seem to be quite determined in their goals, and I was really surprised at this. At first, I thought it would be more of a social group like the Cartoonists & Illustrators Society, but they do seem real bent on attaining these goals. I don’t see how they could fail to succeed to a small degree. No matter how much they succeed, it will be an improvement. I think something will come of it, I really do. I was really amazed at the interest some of the fellows had in it. Some have different interests than others. Many are in to see if we can attain a better financial status, more benefits and to just improve all aspects of the business. There are other fellows, I suppose, who don’t care much about the financial aspect of it, they just want to present their ideas, their own type of stories, to improve the books in that respect. But I feel ACBA will improve the whole field; the financial end, the upgrading of the books themselves, and maybe a new line of books. I really feel they’re trying all these avenues. I think they’ll be successful to some extent.

GROTH: Did you get many interview requests years ago?

No. I was never interviewed at all until I won a couple of those Alley Awards. And then I would get requests through the mail, for interviews and drawings, and things like that. I appreciate it, and I try to fill everything that’s requested of me. It’s hard at times, but it’s what I would want if I were a young fellow, and requesting this from someone else. In other words, I put myself in the other fellow’s place. I do appreciate the interest they have in me. I hope it’s sincere, and I’m sure, in most cases, it is. I do some drawings at the con, but I would rather do most of them at home, and have the fellows get something a little better than they would get down there, holding the pad on my knee.

GROTH: What do you consider to be the best all-time comic book strip?

Well, I really do feel it was the Fantastic Four. Not because I was any part of it. I feel that way because of the characters — the secondary characters. I feel that the Thing has been the best character since Superman and Batman. I really do. I don’t feel that he’s been exploited enough, however. I do feel that the secondary characters — the Inhumans were never exploited enough either. Y’know, the secondary characters that Jack had running through his book — so many of them. Dr. Doom, Silver Surfer and all these. I think you might well agree with me on that, Gary. What do you think?

GROTH: Yeah, I agree. I think the FF has been the showcase for more imaginative characters than any other long-running series.

But then again, maybe it was because I was so close to the FF. The DC books — I’m really not knowledgeable enough — I don’t follow them that much. I’m not aware of the changes going on over at DC. I do buy Batman occasionally, I really enjoy Dick Giordano’s work. Dick’s a good friend of mine, and I like his work. I think he did a terrific job on the Neal Adams Batman.

VOHLAND: It looked like Jack Kirby’s work on the last issues of Fantastic Four and Thor were rushed, it looked like he was slipping a little.

Well, Duffy, like I said before, I couldn’t see this. I could see it in some of his covers, but I couldn’t see it in the stories themselves. Maybe I just haven’t looked at them that closely. But like I said before, some of the stories he did a while back were much better than some of the later ones. Number 98, the story that took place on the planet — the prohibition-type characters. I thought he knocked himself out on those three. Frank Giacoia inked one of those books as I just needed a break. But I thought Kirby did a terrific job on that story. But like I said, he has his peaks. After a terrific story, it seems he does have a little let-down. But his letdowns aren’t much, and he comes bouncing right back. You might have seen something I wasn’t aware of. Although I’ve heard many people say this — that they felt his last two books weren’t up to par, that he was rushing them, knowing he was leaving, but I really couldn’t see it. If you saw the pencils, you wouldn’t say that. I mean, he certainly put everything in there. He shaded every little button and detail in. He’s gotta be twins! Even when he’s not at his best, no one can tell a story like Jack!

GROTH: Y’know, I see a lot of your drawings — your fully inked illustrations — in fanzines, and they resemble Kirby very much.

Well, some zine editors will write me and ask me for a drawing of Mr. Fantastic or the Thing or Johnny Storm or something like that. Well, naturally I draw it myself, but I’m drawing it the way Kirby drew it, at least the way I felt he drew it. And it comes out looking like the way I used to ink it for Kirby. Well, I did change Kirby’s heads a little bit, not much, but just a little bit. So, naturally, the stuff came out looking like Kirby’s work.

GROTH: A while ago, you mentioned Frank Giacoia. He inked a couple Fantastic Fours a while back and broke up your “run” of them. Why was this?

Well, I think this was during the time of the last convention, and I wanted to go to the city. I was quite tired and I wanted some time off. I was really jammed up, and I wanted about a week off. So, they had two strips coming up at the same time, Captain America and the FF. So I called Sol [Brodsky] and said, “Sol, I can’t do Captain America, I can only do one because I’ve got to take some time off, I’m climbing the walls.”

And he said, “Joe, Stan would rather have you do the Captain America.” He felt I was doing a good job, I had just started inking the Colan Captain America, and he didn’t want to break that up right away. He said, “He’d [Stan] rather take you off the FF this issue.” Giacoia could’ve inked the Colan Captain America just as well as he could’ve inked the FF, but that was the reason I didn’t do the FF that issue. The same thing happened a few issues later.

GROTH: Would you have preferred to ink the Fantastic Four?

Right. Only for the reason that it did break up that run. In other words, I felt that I did so many of them that I did want to continue with the FF. In fact, I would’ve liked to have inked John Romita’s FF if John had done the complete penciling. He does beautiful work. He’s got nice figures and it’s easy to ink. I did want to continue on the FF and am happy that I’m back with John Buscema. I really like working with John.

GROTH: John’s brother, Sal, said that John’s pencils are so precise and perfect that inking them, no matter how good they’re inked, almost ruins them.

That’s right. You can’t improve John’s work, really. For example, his girls have little noses. If you’re not careful, you’ll ruin that nose and it won’t look like his character. You can’t really improve his work. His men are handsome, they can’t be more heroic, his muscles are perfect, his action … There’s just nothing you can improve on John’s work. Nothing.

GROTH: Are there any inkers today that are still influencing your work?

Gee, I don’t think so. Although I always liked Giacoia’s work, even when he was working at DC; I used to like the way he inked the romance books. But I never copied any inker when I first started out in comics, I used to copy Caniff when I was a kid; and Alex Raymond. I used to copy their styles a lot. When I went to the Cartoonist’s & Illustrator’s School I went to Raymond a little bit. Although I wished I had stuck with the Caniff style because he was much looser.

You see, Raymond had a tendency to tighten you up. Everything is more precise. But, I never really copied anyone’s inking. Inking just came naturally. I had periods years ago when I just turned out some horrendous inking because I overinked everything. In fact, I like the way John Severin — I mean — Severin is probably my favorite all-around artist, adventure artist. Buscema is the best illustrator. John is really an illustrator. He’s the best in the business, I feel. Severin is the best all-over adventure artist, I feel. He does the best war and the best Westerns and his humor is unsurpassed. His authenticity is just great. Everything’s just perfect. And I also like the way he inks. He’s got a rough style that is completely harmonious with his type of story. I really wish I could ink like Severin, although it’s completely different from mine.

GROTH: I think Tom Palmer is one of the very best inkers in the business. Do you enjoy his work?

Very much. In fact, I was looking at some of his originals yesterday. I was amazed at the effort he puts into his work. The Zip-a-tone and special effects. He must have spent a fortune on Zip-a-tone, and it must be very time-consuming. He plans everything so thoroughly with the different patterns of zip-a-tone to create such special effects. In the smallest detail, in the smallest areas.

It’s amazing. I think the originals — the reproductions are great also, but the originals — they look beautiful. I have never used Zip-a-tone, etc. on any of the superhero books that I can recall. I would like to use it on occasion, but I don’t have the time really. I also thought Palmer and Adams was a fine combo.

GROTH: Since we’re talking about inkers on John Buscema’s pencils...

Excuse me, Gary, but I also think that issues 4, 5, 6 and 7 of the Silver Surfer were just unsurpassable, with Sal inking with a special style that he didn’t seem to follow through in later books, but it was solid blacks with no feathering at all if I remember correctly. I thought they were tremendous. Do you remember the books?

GROTH: Yes, that was just what I was going to bring up...

Yeah. I think it was number five that really impressed me.

GROTH: Could you give any aspiring artists tips about drawing and inking a comic book and breaking into the business?

Gee, Gary, it’s pretty hard to say. Like everyone else says, you read it all the time, you’ve got to practice and practice and practice. I mean, I’m drawing all the time. Even when I’m sitting at the dining room table. I have paper.

But I have gotten in the bad habit of, for years, all I draw when I’m doodling, are heads. All different types — cowboys, superheroes. When I should be drawing the body. When I was in school, I drew the body. But I like to draw heads, different characters — all types. Humorous-type characters, everything. I’ve got stacks of the stuff I’ve saved over the years that I just enjoy keeping. But I would say the one thing is to keep drawing the human figure, over and over, in every position. Learning the muscles, just the basic muscles, you don’t have to put the muscles in like Hogarth used to put them in. He was a terrific figure man also. Buscema puts in the basic muscles and they’re beautiful. That’s all you need. I would say just keep drawing the figure.

Gee, I don’t know. I wouldn’t want to discourage anyone from entering the comic book field if that’s what they really like. I think if I had to do it over again, I wouldn’t enter comic books, because I feel that I’m not really enjoying myself doing it. I did years ago when they had the variety and the artist did everything — the penciling and the inking. The stories were fun to do. Superheroes in the past 6-7 years, it’s been a real grind. I’ll say that. It’s been work, very hard work. I enjoy doing the Treasure Chest stories because there’s variety there, but you have to do what you can do best. In other words, right now, I feel that I’m a half-way decent inker and that’s how I’m basically earning my living. I do little things on the side occasionally, like advertising work. They help supplement my income, and they’re also interesting to do, I enjoy doing them. I think I honestly least enjoy doing the comics that I’m doing for Marvel, That’s really what it amounts to, Gary. If I had it to do over again, I would probably — well, I’ve always been a frustrated sports cartoonist. In fact, I did one the other day on Willie Mays. He was about to hit his three thousandth hit. Y’know, he’s the only player who’s had 2,000 hits and also 600 home runs, so when something like this comes up, I’ll knock out a cartoon for the paper, the local paper. I enjoy doing this type of work, and I wish I could do this on a daily basis. But, with four kids, I’ve got to make a half-way decent living and the only way I can do it is by working in the comics, I feel. But I’m not really doing what I “want to do and I guess I always have my eye out for something else to do because I feel that I’m really not happy doing comics. It’s just such a terrible grind. Inking the same thing over and over again. It can become a tedious bore doing the same thing.

It would be different if you were drawing, creating something different, but when you’re inking the same characters, the same background — I mean, basically the same type of thing over and over, it’s like an assembly-line production, which is what it really is. It is quite a chore, and I feel I should get out someday, and do something I really enjoy doing. That I think I would like to do. In fact, I would like to do fashion work. I have done some in the past. I’ve just done some about a month ago. I really enjoy doing that. But, y’know, I like comics. I’ve been saying that I’m going to get away from it for years, but I’ve always stuck with it. There’s a certain satisfaction, even today, of seeing your work in a comic book, though. Even today, I keep all my comics. Some of the things I wouldn’t show anybody because I’m not proud of them. It would always be nice to have a syndicated strip someday too. I guess that’s the goal of every cartoonist. But I really wish I had a character very much like Beetle Bailey type. When I was in school, I had a character very much like Beetle Bailey, this was before Beetle Bailey came out, and I wish I had followed that through. I thought I had a feel for that in those days, and I really enjoyed doing it. But at the time I could also draw realistic type characters.

At the C&I School they kept pushing me towards the realistic type of comic strip and then, naturally, when Tom Gill got ahold of me I was doing the realistic type comic work and that’s what I continued to do. But I really enjoy doing the light Beetle Bailey type thing. I wish I had gone through with that, but I guess everyone had those same aspirations, wishes and regrets.