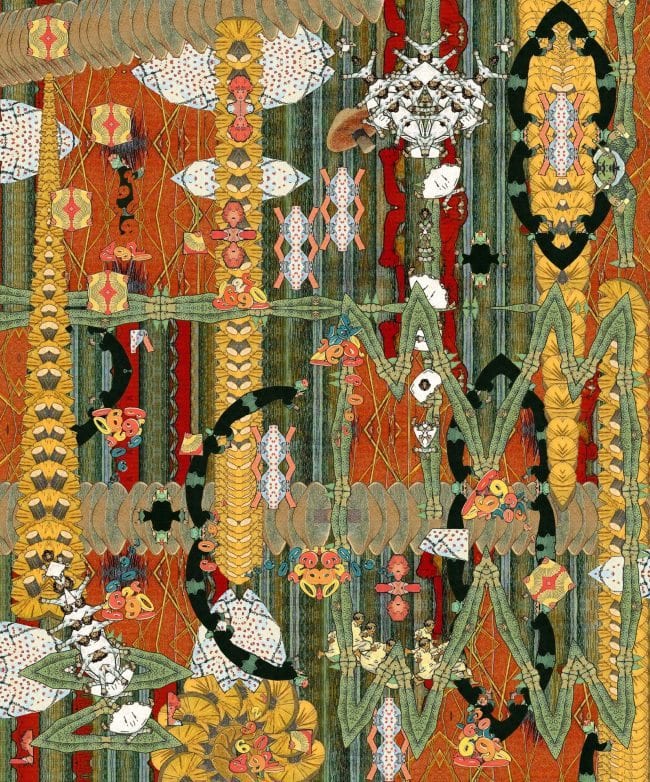

A quiet revolution in comics—as relates to its connection with fine art and design—is staged on the tumblr of Yvan Guillo, under the pen name of Samplerman. Using castaway imagery from comics—much of it found at free websites like the Digital Comics Museum, and Comic Book Plus—Guillo creates breathtaking, playful kaleidoscopic images that have, until recently, been confined to the web.

A quiet revolution in comics—as relates to its connection with fine art and design—is staged on the tumblr of Yvan Guillo, under the pen name of Samplerman. Using castaway imagery from comics—much of it found at free websites like the Digital Comics Museum, and Comic Book Plus—Guillo creates breathtaking, playful kaleidoscopic images that have, until recently, been confined to the web.

With the self-publication of Street Fights Comics (2016, and one of my picks for the best comics work of that year.) and a new, self-titled 44-page art book of Samplerman images published by Los Angeles’ Secret Headquarters, the time seemed right to talk with Yvan Guillo about his delightful, dizzying and thought-provoking comics art and how it’s created. This interview was conducted via e-mail in January and February of 2016. Guillo has chosen a selection of some of his Samplerman favorites to illustrate this piece.

Do you consider yourself a cartoonist? What led you to creating your "Samplerman" persona?

I am a 46-year-old cartoonist. I've been writing and drawing comics for more than 25 years, without any popular success, I have to admit—perhaps because of a lack of self-confidence, not harassing publishers enough, taking no answer for a "no thanks," and no longer posting my pages (lots of improvised and unfinished stories) on my obscure blogs.

I have always chosen the DIY way to make my fanzines and minicomics: it is affordable and it mostly requires commitment and time. Due to lack of feedback, I've felt discouraged from time to time. Sometimes I can't believe that I’ve kept doing this for so long instead of finding a real job...

I've been obsessed with comics all my life. I would have liked to be a comic strip cartoonist, but that career doesn't exist in France. The conventional formats here are the hardcover, annual 44-page book or the black and white, 300-page one-shot graphic novel. I've always been attracted to arts of all kinds: poetry, radio, cinema, animation, the avant-garde, experimentation and the borders of communication. I’m also drawn to abstraction, distortion, destruction, surrealism, sociology and politics. Most of my past comics are kind of absurd and meaningless (nonsensical, to say it nicely). At the end of the day, whatever I am doing, the path from a panel to another has become for me the ordinary way to explore this alternate reality (comics) where I feel at home. So yes, I think am a cartoonist; a weird cartoonist.

Hence the question could be: "Are the Samplerman pieces strictly comics?" I would answer: "Depends on how restrictive your definition of comics is." If the reader considers certain of my "stories" just as a sequence of panels without any logical connection, I am fine with that, but my works are at least a failed attempt at doing a story from a cartoonist's neurasthenic brain.

At the start, "Samplerman" was a side project. The first attempts sat on my hard drive for months before I posted them. These were very simple panels, in low resolution, that displayed samples of web-downloaded scans of "Superman" or "Fantastic Four" that I had duplicated and symmetrically joined: the most basic manipulation. The abstract visuals resulting from this treatment didn’t corrupt the seduction of the original drawings and colors, which were visually familiar though modified, like comics seen through a distorted mirror.

I thought that it would be fun to make a parody of a comics using this method—a 36-page kaleidoscopic comic—and then I would go back to my old hand-drawn comics. But when I posted these few pages on my tumblr la Zone de Non-Droit/the No-Go Zone, which I share with my friend, the cartoonist Léo Quiévreux, the feedback for these posts was quite strong. Soon a publisher asked me if I had plans to make a book. I decided to dig deeper.

I thought that it would be fun to make a parody of a comics using this method—a 36-page kaleidoscopic comic—and then I would go back to my old hand-drawn comics. But when I posted these few pages on my tumblr la Zone de Non-Droit/the No-Go Zone, which I share with my friend, the cartoonist Léo Quiévreux, the feedback for these posts was quite strong. Soon a publisher asked me if I had plans to make a book. I decided to dig deeper.

The pseudonym (more than a persona in my opinion) is the term that I was putting as a hashtag (#samplerman project) each time I posted these things. I am doing various kinds of comics which attract different tastes and interests, so the pseudonym is a simple way to not confuse people. It has its issues, though. I haven’t figured out how to display my different universes on the home page of my website, and I still wonder if I should give up the part of my work that remains unpopular.

The “Samplerman” title refers to how my work has conscious musical connotation (by the way, a Spanish DJ used this same pseudonym before me). There is a fabric and pattern association as well, and it's kind of a stupid superhero name: Superman with a patchwork outfit. The name came to me in one piece in my brain without too much thinking. And the people who contacted me about this work by referring to this word adopted it too.

How do you approach the anonymous vintage comic books that you use to achieve your collages? Have you taken advantage of the enormous body of digital scans available on Comic Book Plus, Digital Comics Library, etc.?

I approach these old comics with gluttony; and, yes, I visit these websites all the time. I am not a specialist of American comics. I didn't read them as a kid, even though they were widely available here. I am constantly discovering and learning about the artists of these past eras of comics history. As my knowledge slowly and randomly increases on the subject, I no longer consider these comics anonymous. I am constantly amazed by the designs, the styles, the variety and the energy displayed there.

I want to download everything, but there are so many comics available that I wonder if I will be able to get everything. I find something interesting and usable in almost every comic I get from those websites. Without these incredible resources, I wouldn't have been able to fill my pages with so many diverse graphic elements, and I wouldn't have produced as much work.

I am like a kid surrounded by an infinite stack of comics, A kid who doesn't really read, and can't follow the stories, but immerses himself into the universes found in their pages. With gluttony and delight!

I didn't know about these sites at the beginning, when I wondered if I’d be able to produce more Samplerman pieces... I encountered them at the right time. I also appreciate their principles of scanning only public domain material. It prevents me from using copyrighted works, and the risk of getting myself into legal trouble, which I can't afford.

My only regret: Sometimes the definition and the quality of the scans aren't good enough to be used. It’s too pixelated, or too compressed, but this remains a bottomless source for my pieces. I’ve started to buy some physical copies of old comics on eBay, so I can scan the pages myself and get the best quality, but I’m not rich. I have to make choices.

In "Street Fights Comics," you obviously sought out images for the purposes of building a free-form comics narrative. In your regular "Samplerman" images, which you post on tumblr, you create stand-alone, poster-like images. Which approach is most artistically rewarding to you?

It seems like I make either right-brain or left-brain comics. Both are rewarding in their own way. I have a formal, pictorial approach which requires spontaneity and embraces randomness, open-mindedness and non-verbal communication. I put myself in a sort of trance and start working with no pre-existing plan. I start by choosing a template for a page (a six panel or a more unconventional template). This is my only constraint. Then I compose my page. This is a bi-dimensional visual reality. This kind of work is made for viewing rather than reading—it's the side of Samplerman that no longer belongs to comics.

And there is the more intellectual approach, which involves more humor, sense/nonsense and collection/repetition. The idea of collecting the pages into a book was in my thoughts almost from the start. And, yes, Street Fights Comics belongs to this.

It requires preparatory work—collecting and gathering elements connected to a theme and a vague idea of a story. The balloons, dialogue and transitional signs ("meanwhile," "after that," "then" etc.) play a more significant role for this kind of comics. They are more linear and kind of realistic or surrealistic; the human figure is more present and more consistent, and there is a ground and a sky. But they are contaminated by the other approach. As long as I forbid myself to write my own text, they will fail to tell consistent, normal stories.

I work like I’m playing a game, with constraints, but I like to change the rules to avoid boredom, or becoming a living algorithm. I follow the paths that appear one after another. Sometimes I have a stupid idea like: "What if I made a hole in a page, or a panel, to see what happens?" I am interested in Brian Eno's "Oblique Strategy" cards, which I consider an exciting tool that helps push the boundaries of the creative process.

A sense of absurd humor informs all your work. Do you find some of this humor inherent in the 1940s and '50s stories you dissect for your work?

The comics of all eras contain involuntary and voluntary humor. Reading them 70 years after their first publication inevitably leads the reader to find it at times laughable, stupid and ridiculous. The serious comics (romance, horror and war comics) contains a humor that comes from a propaganda-oriented way of telling stories. Commercial and advertising comics are especially funny and ridiculous. This is seriousness from a period when comics weren't taken seriously including by their creators.

Some texts are pure genius. I have in mind the panel from by Fletcher Hanks where a bunch of evil characters say: "We must end democracy and civilization forever!" I find this funny and terrifying at the same time. I also take my material from comics which are still actually funny: the newspaper comics from the 1920s and ‘30s, Herbie, Plastic Man, Abbott and Costello etc. My use of the source material isn't always in contradiction with their initial meaning.

I’m always looking for a strangeness, a silliness in the juxtaposition of dialogue balloons I extract from these extraneous stories. What makes some of my panels funny is the misplacement, the décalage. It can be unexpectedly realistic: in real life we experience people talking without really listening to each other. The practice of collage prevents me from going where I wanted to go in the first place. With collage, you have to play with what you have and be open to unexpected results—a different meaning and many possible interpretations and reactions from the readers, including laughs.

Patterns and textures are a big part of your stand-alone images. You create these patterns from insignificant images within comics panels—hats, hands, shoes, even lettering. Do you see patterns emerge from the original comics sources as you examine them? Or do you isolate these elements and play around with them as you design a new page?

My method is flexible. As someone who make collages and draws comics, I might have the ability to notice, as I flip through the scanned pages, which element will produce a better effect and be magnified by duplication and the kaleidoscopic treatment.

I’m drawn to the primary bright colors mixed with halftone printing dots, overlapping and crossed lines—the organic melting of the ink with the paper. Some panels are likely to express the joy the artist had when he drew a specific element. It's often half-abstract, half-figurative: women’s hair, cigarette smoke, sea waves, clouds and in animals like snakes, elephants or octopi. They were opportunities for the artist to escape the story and give some freedom to their hand and pencil.

I enjoy mannerism in art. I enjoy the variety of styles: some artist show their obsession for details (Basil Wolverton) and some are more gestural. The rounded "toon" style has its own very interesting energy.

I usually come across a comic where the components triggers a compelling desire to make a collage. I select, cut out and place the elements on my composition. At the same time, I try to keep them in an organized image bank. This process slows me down a little. Sometimes I don't file the elements, which I regret later, because their large number makes it difficult to remember which comic I found them in. Sometimes I revisit my image bank to reuse the elements. The same element can be used on its own or transformed into a pattern. I also have a "pattern" section in my image bank.

I would imagine you use Adobe Photoshop, or a similar computer program, to assemble your images. Does your creative process occur within those programs? Or do you make sketches or do other pre-planning before each image is assembled? Some "Samplerman" images seem extremely composed, while others have a feeling of spontaneity. The blending of these two opposites is a compelling factor in your work.

The creative moment occurs mostly when I face the computer screen. I only make sketches when the computer is not on—when I take a walk with a paper and pen in my pocket, or when I have an idea related to structure or geometry for potential compositions. I am always thinking about some elementary geometrical manipulations, combined and applied to the samples. Squares, triangles and circles are everywhere. And I fear this is where my work could start being boring and repetitive—I could apply this to anything.

I try to keep a sense of movement in my work. Sometimes I feel the urge to break my composition, to destabilize the eye-scan and push it toward the next panel. I tend to use symmetry a lot when I start putting together a background and the elements. It's somewhat satisfying but at the same time it paralyzes any feeling of movement. I usually end up distorting the symmetry I rely on. I try to give it a shake and extend the life of these unearthed objects in any way, like a mad scientist.

Your use of color adds a great deal to the Samplerman images. Do you ever alter the color of the material you source from old comics? Or do you use the found images as the basis for your color choices?

I make only the most minimal changes to the color. I may change the colors from parts of my samples for special effects, but I try to stay within the four-color spectrum of the letterpress printing technique that dominated comic books until the 1990s. It’s possible that I'll break this rule in the future, and take the license to make more extreme adjustments.

I correct only the black and white balance. The scans are so different, with various dominant colors from one to another. I like the yellowish tone of the aging, low-quality paper. I want the general tone to remain moderate—not too saturated but bright. When my pages are selected to be printed, I convert them to the four-color process and inspect each channel. The colors have a great impact on my choices and they trigger my creativity. When I compose a panel, I often look for a particular color in whatever element I pick.

I assume you are aware of the work of 1950s comics collagist Jess Collins, whose "Tricky Cad" pieces are brilliant dissections of "Dick Tracy." Though your work goes into far different places, has Collins been an influence on your Samplerman pieces? Are there other collagists who have inspired your work?

I must confess that I only heard about Jess after I started my project. I immediately looked for his pieces when someone compared my work to his. From the examples I’ve seen, there are definitely some similarities.

Other artists came to my attention after I began my collages, so I can't say they influenced me, but I’m curious to see what they have been doing by using the same approach and material. Öyvind Fahlström (1928-1976) is another artist I recently discovered. Some of his pieces remind me of mine, except he made them four decades ago.

Other artists who have made a strong impression on me, not so long before doing this kind of collage myself, include Ray Yoshida (1930-2009), who systematically collected samples from comics during the 1960s; his pieces are very nicely composed. His work brought to me the idea of making collections of items that appear again and again from one comic to another. Some comics have influenced me for my collages even though they weren't collage: I have seen a lot of character removal approaches in art, leaving background spaces empty.

I was quite impressed by the "Garfield Minus Garfield" project. This kind of intrusion into someone else’s work inspired me towards other kinds of manipulations in comics. In a similar vein, the French cartoonist Jochen Gerner has revisited Herge’s 1931 Tintin en Amérique album by highlighting, on a black background, its many symbols and signals in a half-comics/half-artbook untitled TNT en Amérique. I remember a story by Art Spiegelman (1976’s “The Malpractice Suite”) in which he drew extensions to panels of old comic strips.

Artists reading other artists’ work creatively have attracted my interest for a long time. My best friends are not cartoonists, but they have influenced me too. They make digital and "real" collages (with glue and scissors): Laetitia Brochier, Frédox and Jean Kristau. Their work is published mostly by Le Dernier Cri in Marseille. My friend the cartoonist/illustrator Léo Quievreux creates drawings that look like collages. He is influenced by William Burroughs' cut ups and has managed to make visually similar experiments. Pakito Bolino, who runs Le dernier Cri, makes secret collages (in the sense that he rarely displays them) that blend manga, E.C. horror comic, old horror movies and pornographic photos, which he uses as a basis for his drawings.

I’m also fascinated with the meme phenomena on the Internet: the sprawling, unleashed creativity of an anonymous community of unconnected artists. And I must pay tribute to the collages by Max Ernst, based on 19th-century engraved illustrations. I’ve loved them for a long time. Twenty years ago, I went to a Kurt Schwitters retrospective, and I consider his work important, if not directly influential on me. A few more names: Chumy Chùmez for his book Una Biografìa, Roman Cieslevicz, John Heartfield and the Dada movement.

NOTE: A new printing of Street Fights Comics should be ready when this interview is published. The first run of 50 copies sold out quickly. With its republication and the Secret Headquarters art book, plus Miscomocs Comics, an existing compilation published by Le Dernier Cri, the “Samplerman” side of Yvan Guillo may be on the verge of wider global recognition.