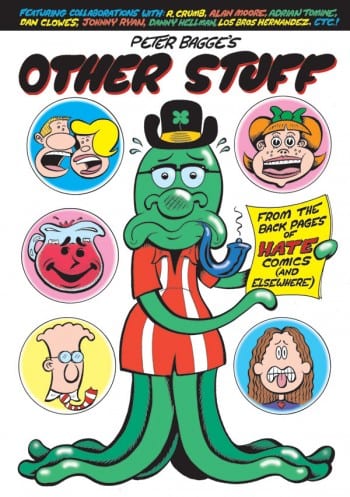

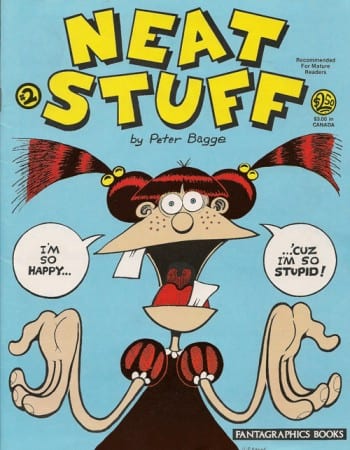

I've been wanting to talk to Pete Bagge for a long time, at length and in-depth. And on tape. For myself and many others, I was introduced to Pete's work in Neat Stuff in the mid-'80s, and it changed everything: smart, anarchic, insightful, and funny as fuck on a level I'd never seen before (or since) in comics (or anywhere else). His editorship of Weirdo followed by Neat Stuff followed by Hate was a run pretty much unparalleled in comics-- maybe a handful were as good, but you could count them on one hand (or a couple fingers). And besides, it's apples and oranges: there was no one like Peter Bagge, and there still isn't. What you get from him is unlike anything or anyone else, in all the ways that matter. I've felt for a while that the rise of so-called "art comics" left Pete somewhat unappreciated in the current landscape of "serious" "literary" "graphic novels," which I think is a damn shame: his work is still great, above and beyond what the flavor of the decade might be. It could be that I had some bones to pick on that front, but Pete was honest and classy and generally refused the bait (actually, the very first session was as close as I got to actually working him into a froth, but, in a case of "the interviewer's worst nightmare," that conversation was lost because my recording device shut down 22 seconds in, without my knowledge). Mostly, I just enjoyed talking with him: he's one of my all-time favorite cartoonists, and I'd listen to his perspective on anything. We conducted the interview in two long sessions (after the first crippling loss), a couple months apart, then both edited it for clarity. Enjoy.

Zak Sally: I kind of want to try and get an overall perspective of where you started, what you moved to, and where you are now, at the same time kind of tracking what's going on with comics right now, and sort of your movement through that.

Peter Bagge: Okay.

Okay, so you started off reading newspaper comics and you had the influence of your brother, who wrote and drew, and then you went to SVA and the comics program there-- but you ended not taking any comics classes, right?

Right, I only went for three semesters. I went to the School of Visual Arts back to 1977. The first year you had to take a little bit of everything. The second year you could choose electives, and I wanted to take all the cartooning classes but I got talked out of it. I was a total wuss. The counselor convinced me to not take any cartooning classes. She knew what was going to happen: that I'd take all the cartooning classes and then quit. And that's what I was going to do. I don't know why I let her pressure me from changing that course of action. She had some line of palaver that convinced me that wasn't the thing to do. So I took another semester of garbage, with terrible incompetent teachers that never showed up.

They actually never showed up?

They actually never showed up?

Or they'd show up late with a hangover. I can't even remember any of the classes I had in that third semester, just because they were so all about nothing. I really have zero memory of what the classes were. So I quit, though I also ran out of money. I had to work a full time job, I was living on my own by then, and a part time job wasn't even going to cut it. So I kind of had no choice but to quit.

Okay.

I did take one evening cartooning course. It was taught by a guy that used to write and draw for MAD Magazine, named Peter Paul Porges. But for some reason he missed out on half the class, so the first half of the course was taught by a guy named Sam Gross, who lived up to his name. He did really gross gag panels for National Lampoon. And he was great.

Did you have any classes with Eisner? Or did you sit in on any of his?

I sat in on one of Eisner's classes, just once. People told me he was a very good teacher, but the whole time that I was sitting there, he was surrounded by this handful of guys who you could tell wanted to be superhero artists, monopolized all of his time. I barely saw him address the whole class, so I wasn't going to go back to that.

I sat in a little bit on Kurtzman's class. Mainly I just wanted to talk to him, and this was quite a few years later. I talked to him about something, I can't remember what, but I think I was starting to self-publish, and I showed him some of the stuff I was self-publishing stuff at that time with a guy named John Holmstrom. And Holmstrom and Kurtzman knew each other, Holmstrom was a student of Kurtzman's.

Was this before -- are you talking about Punk Magazine, or are you talking about—

It was right after Punk, we're talking about Comical Funnies, so this would have been a couple of years after I quit art school. In the interim I met Holmstrom. I was a big fan of Kurtzman's, but by that point it seemed like he really wasn't a very good teacher; he was mainly just baby-sitting. And for some reason he was teaching all the students to do single gag panel, New Yorker-type cartoons. Which he thought was the way of the future. He couldn't have been more wrong.

Yeah.

Comic books pretty much exploded after that, and he would have been the perfect teacher for that. He never was a gag panel guy anyway. What was he thinking? (laughs)

That's so weird. I mean, I know that whole generation was all about the, you know, 'You've gotta make a living at this, sonny' and doing whatever you needed to do to try and make a living.

I also sat in a couple of times on Spiegelman's class. But then I got to know Spiegelman a bit outside of school, and would talk to him every now and then. He was very cantankerous in those days, he was very "my way or the highway," and since I didn't see eye-to-eye with him on a lot of things, it could a bit uncomfortable to talk to him.

Did he like your stuff?

No [laughs]. Well, certainly not much. My work was very crude then anyway, so there wasn't much to like. But he was very informative. He was a very good teacher, and an incredible fount of information.

I'm wondering now, I want to loop back a little bit, because one of the things I want to get to is a question that I ask a lot of cartoonists: what possessed you to think that you could actually make a go at this? And that comes up a lot with me teaching at MCAD. A lot of people have been talking about the fact that these students are paying this pretty exorbitant amount of money with absolutely no guarantee of assuredness that you could make back that money in this field. You know, like, "You just got a degree in comics art."

Right. But you could say the same exact thing with English majors, and psychology majors, and women's studies majors. And what about all these people majoring in sculpture and ceramics? And how many painters does the world need? So that's true with everything, not just comics.

Yeah, I think it is, but I think those things might be a little more respected. Like if you hit it big, or if you go through these certain channels you might be able to do this, whereas the comics people are a little bit more like, you know—there's no money. I think comics might have a little bit more of--

Well I think probably anybody who went to art school, and their main focus was comic art, I think they'd have just as good a shot if not a better shot than a lot of the fine-art majors in making some kind of a living off of what they went to school for.

I mean, I tend to feel that way too. I'm just wondering if, you know with that counselor telling you, "Don't take the comics classes," this has been an ongoing attitude throughout the ages.

But they also only had three cartooning classes back then, and lots of people would take those classes and then they'd quit. So she just figured I'd fall into that pattern.

Okay.

But yes, comics just was a lot less respected as an art form than it is now. It's come a really long way; people don't look at you cross-eyed when you say you want to do comics anymore. Back then it just meant that you were a moron.

[Laughs] I kind of wish, in certain ways, it still did.

Oh, man, don't get me started, I totally wish that. Or at least partially wish it!

Oh, we'll get there man. [Laughs] Don't you worry about it.

The reason I say that is if you wanted to do comics back then it meant you really wanted to do comics. And I also like that you were able to fly under the radar back then. Nobody was doing it for accolades, and hoping to get a good review in the Times or win an award. There were no awards back then. So you just did it for the love of it, you did it for the fun of it. Or you just HAD to do it.

This is something else I wanted to talk about, your whole generation of cartoonists—you know, the brothers Hernandez, Clowes, all those guys— the amazing thing to me is that the climate for comics was so different back then. In the lost interview we talked about what possible models you could have had for thinking I'm going to try my damnedest to make a living off of this, because there were virtually zero models for this outside superhero or genre stuff. And then for you it actually worked. I mean we talked about the fact that you found some old undergrounds, and you found a Crumb comic-- and those were...

Well, to back up a bit, I fancied the idea of being a cartoonist since I was a kid. I mainly liked daily newspaper strips, all the funny stuff, and later MAD. But after a while, those two seemed less and less a realistic option for me. I saw the daily strips getting worse all the time. By the time I got out of high school I didn't see anything in the daily papers that inspired me, or made me think, "This is a good direction for me." The opposite was happening. And MAD was very much a closed shop, and locked into a tight formula, and I didn't like MAD's competition much. So while I still fancied the idea of being a cartoonist, I didn't know what to do with it.

Then, while I was in art school, I went into a record store that had a rack full of underground comics, and it was the solo comics by Robert Crumb, in particular, that floored me. What I loved about Robert Crumb's solo comics was how he treated the traditional comic book format as a blank canvas, and just did whatever he wanted from cover to cover. It was all him: one guy inked it, one guy lettered it, and there were no ads for Twinkles or BB guns. It was just all him. And then there was what he did with it. I loved the way he drew, and I loved his sense of humor just as much as that I loved what he did format-wise. So as soon as I saw that, I knew that was exactly what I wanted to do. And while Crumb was my favorite, I liked many of the other underground cartoonists, too: Gilbert Shelton and Bill Griffith, and a lot of others. Kim Deitch, Robert Armstrong, and Aline Crumb. Sadly, I also assumed that since their comics were so fantastic, they must all be millionaires.

[Laughs]

I was like: this stuff is just too awesome for everybody else in the world not to go crazy over. I should have realized at the time, if this stuff is so popular, how is it that I didn't come across it till now?

Yeah.

Wait, what year is this, Pete?

1977. And that's the other thing: I didn't notice at first the copyright notices in these comics I was buying, and it took me a while to realize that out of the fifty or so underground comics I wound up buying, only like two or three were copyrighted the year that I bought them. The rest were like from roughly 1968 to '72 and were just being reprinted. So that's when I started to wonder what was going on with this particular style of comics, these undergrounds. Why were there so few coming out? Later on I learned that pretty much the only underground cartoonists that were making a living off of their art were Crumb and Gilbert Shelton and Bill Griffith, and even then they were far from loaded.

Yeah. That's even kind of interesting, because when those were coming out initially, the whole country was probably lousy with them. I mean they were doing amazing numbers on those books in terms of print runs, right?

And that all ended in 1972 for a whole bunch of reasons. The whole underground market collapsed by then.

And the next time there might have been an underground movement was-- and feel free to correct me here— when sort of underground, fringe comics were selling those kind of numbers was probably ... I mean, what were you doing in the heyday of Hate? It was big numbers, right?

Well, some of the early underground comics, like the Zap Comix from the late '60s and early '70s, sold in the six figures, including reprints. Hate and all the other more popular alternative comics from the 1990s never came close to that. I think the first issue of Hate, if you include all of its reprinting, the first issue of Hate probably sold at the most forty thousand.

Okay.

For most of the run of the title it was more around twenty, twenty-five thousand.

Yeah, that's still- You know, those just might have been two spikes in the underground, because comics now, I don't know if anybody is hitting those numbers, are they?

Well, few people are doing comic books these days. Everybody's doing graphic novels. So that's a big change. You could sell five thousand, but since it's selling for twenty bucks, that's good, or at least profitable.

I want to kind of dig into that a little bit more, because, you know, I bought Apocalypse Nerd when it was coming out, and I purchased Reset in "pamphlet" format, because that seems like my favorite way to experience your stuff, rather than as a "graphic novel." Do you miss the periodicals?

Yeah, very much so. I like they way they feel. To me it's an ideal format, the traditional comic book format. It's the perfect amount of material to read in one sitting. You don't have to cut out a big block of time to thoroughly absorb it. It's just very cozy, and then curl it up and stick it in your back pocket, you know?

Yeah.

Whereas with graphic novels, it's just more of a commitment. It's not as portable, and also there's just something about that format. Publishers want to be able to charge a decent amount of money for a graphic novel. It's all about the profit margins. So they go with varied formats, hard covers, endpapers, a dust jacket. They want it to be fancy, because then they can justify charging more money for it. But when you have all of that hooha it's like trumpets are blaring, you're rolling out a red carpet. Before you even crack the thing open it's reeking of self importance, and a part of you is thinking, "This better be really good." It must be profound! And with a longer story the reader is expecting some kind of profundity. The format is declaring ahead of time that the work is "important," rather than having the work speak for itself. It's also a format that doesn't work for anything that's intentionally lowbrow or irreverent. It's like dressing a pig in a tuxedo, and I don't mean that as an insult to pigs.

I think for me now it's almost like the tail is wagging the dog. It feels like people are creating comics in this way that it has to fit into that mold, and for a lot of folks, that's not really what they have to say, or want to say. They just feel like they have to be profound...

Right. [Laughs]

You know, I've read a lot of ... now I'm kind of chickening out of listing the actual books and cartoonists. Well no, I'll just say it. Did you read Wimbledon Green, Seth's book?

No, not yet.

You know, to me it was a perfect example of this. He was kind of making up this whole thing about fake superheroes and fake comic book collectors that were all over-the-top -- you know, it was just this completely goofy story that started in his sketchbooks. And he kept on working on it, and it was really funny, and really hilarious and crazy, and then I swear, in that book, I felt like I could watch him saying, "This is not serious." Then stuff started to come in about his childhood and his mother, and by the end of it I felt like, Man why did you do that? You had this totally fun, goofy comic that I could see you purposely changing into something serious, when, for me, it was to the detriment of my enjoyment of the thing. At the end of it, I was like, "I want to hear more about these goofy spy comic collectors," you know? I don't want to-

Huh.

And I see a lot of that kind of shoehorning; you know, trying to live up to the perceived seriousness in comics. Whereas, with someone like Jaime [Hernandez], recently with the "Love Bunglers" material, it is profound, and deeply so, but it happened in a way that is just natural. It's just what he does. He's not doing it to get on the New York Times book of the year list.

Right. As far as we know, anyway. It does come across as very natural. And also, it all just seems like it's part of this long line, like part of everything he's ever done all these years. So with someone like him, it never reads like, "Okay, now he's putting big boy pants on."

Hey, are you a fan of King-Cat? And you can say if you're not. John Porcellino's comics.

Yeah, I like his comics. I like Seth's work, too, by the way.

Yeah--there's stuff by Seth that I think is great. That just was one of those books where I first noticed that thing going on, in a way that kept me from enjoying the book as much as I felt like I could have, or should have, so that's why I called that one out. I ask about if you like John's stuff just because I did this interview with him for the Journal a good long time ago, and at that point not many collections of his stuff had come out, from big publishers or anything like that, and he said, "Those books are fine, but King-Cat the comic is the thing." You know? "That's the thing that I'm trying to say. The collections and other stuff are sort of interesting, but what I'm doing is King-Cat. The letters pages are part of it, my top forty lists, all that." The big fancy books are essentially weird byproducts of the zine, not the other way around. And I know he still believes that, and so do I…

Right, right.

And I think your tenure at Weirdo, and through Hate, I mean I really, really miss the-

Letters pages? [Laughs]

Well, yeah! Or just particularly with you, and the way you did it, certainly with Hate but also, I think about Weirdo a lot because it was this really inclusive thing. Weirdo, as you might know, I think is the greatest magazine that ever existed.

[Laughs] Says you.

Aw man, see, I just wish- can you just let me take that over? Can you just let me fire that back up? I'll write a note to Crumb-

Go ahead!

Great! The world needs Weirdo more than ever. But I mean, was that purposeful? With both that and with Hate, you were reading the material, the comics, and whatnot, but it was more than that as an experience-- the letters pages, the competitions; it was way different than the impersonal— It felt like you were, in some way, part of this thing, rather than simply reading it. Everything you did had that quality. Far beyond the comics themselves..

Right. Well I very much followed Crumb's example with Weirdo, where he made the letters pages part of the art. It was very careful designed and carefully edited to be as entertaining as possible. He lettered the letters pages by hand, and so I did the same thing. But once I started doing Neat Stuff and then Hate then I had to do type-set, because doing that by hand was insane. He actually got the idea of doing the letters pages by hand from Punk magazine.

[Laughs]

Punk magazine was the only magazine I know of that was almost entirely hand-lettered, which a lot of people forget, and that was something that Crumb loved—that they would hand letter the letter sections—so he mimicked that with Weirdo. And then Dan Clowes used to do that with Eightball. I would say that along with a lot of what Robert Crumb did, I think nobody made a better package using the comic book format than Clowes. He very carefully pieced it together, he would even hand-letter the indicia, and hand-letter and hand-design back-issues ads. I would do that too, but maybe once every five issues I'd come up with a new back-issues ad, whereas he would illustrate something new for every issue. So what would normally be all be filler and house ads, he did all by hand and made a piece of artwork out of it. And like his hand-lettered his letters sections, they always looked beautiful. And they ware entertaining.

They were super-entertaining. And that was there with you, that was there with him. That whole thing has just died.

Hardly anyone else did that, though. Chester Brown did, but the Hernandez brothers—Love and Rockets would have a letters section, but it always read like they just had folks at Fantagraphics put it together.

Yeah, they didn't seem as interested.

And their letters were always very sincere are very serious, you know. "You really speak to me about the Mexican-American experience."

That was my letter, you dick!

[Both laugh.] I'd be insulting them if they really did sweat over it, and carefully selected the letters and all that.

Out of that whole crew it seemed like they were sort of the folks who kept that stuff at a little bit of an arm's distance. Whereas with you or Clowes-- and you know, by you guys, when I was 20 or 19 or whatever, I just assumed that that was a point of pride with a cartoonist, that you did all that stuff yourself-

Yes, but it was tough to gauge if it was worth the effort. I mean, I doubt I'd be able to sell my hand written letters pages from Weirdo! But we also made a point of running critical letters. And best of all were the letters we'd get that just barely made any sense— [Sally laughs] You know, where you could tell that the guy that wrote it is having some kind of a mental breakdown. [Both laugh] Which I'd often learn later they were. And we'd edit all of it to make them funnier.

See, and that's another thing where comics have turned away from that, and I understand that's part of just the whole industry turning. People aren't buying those anymore, they want this other thing, the graphic novel and all that. But with those comics from that era, and I don't mean to sound too deep, because it didn't feel like that, but back then when a new issue of Hate or Eightball came out, it wasn't just the work. You know, there was this whole other part to it. And I miss that.

Yeah it was the format, again, and I miss that too. I could still keep doing it, but it's a lot of work, and then there's the whole economic liability of working in that format at all. It usually takes some persuasion on my part just to get a publisher to serialize it, to make it a mini-series. And then it's a mini-series, which isn't the same thing at all. It's "To be continued," just one piece of a future graphic novel. So there's no sense in shaping an individual issue into something that feels very much in and of itself, because it isn't. I mean, I could do that, but it just seems a bit pointless when you know that this is just one-sixth of something bigger. But I still like having it serialized, just so there actually is this comic book -- that I'm still making "comic books" in some sense. But it's not at all the same thing as Hate was, or Neat Stuff.

(continued)