Yuichi Yokoyama’s first full-length graphic novel, Travel, tells the story of a journey, and ends with a destination. Over the course of its nearly 200 silent pages, readers watch the progress of a train’s riders through a series of stunning, occasionally futuristic landscapes, and are thereby implicated in the journey themselves. The book’s final few pages show the three passengers whose embarkation begins the story leaving the train and taking a quick walk to a sea shore, where the froth of crashing waves prohibits further movement, literally ending the comic in its tracks. It’s a bold statement about form: sequences of panels depict motion, and when the motion must stop so must the comic. Every comic is a journey, a movement through something to something, and as such the only logical end point is a cessation of that movement.

Yokoyama’s second graphic novel, the recently translated Garden, also follows the logic of motion from beginning to end, of journey to destination. But in this book Yokoyama complicates things: Garden also begins with a destination, and for over 300 pages readers are invited to wonder if the journey it depicts is the same utilitarian movement through space depicted in Travel, or an end unto itself.

Garden begins with a strong echo of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. A handful of the artist’s humanoid, fashion-forward characters stand assembled before a guard wearing a mask printed with a pattern that encourages the eyes to unfocus, and are denied entrance to the garden that memories of Travel suggest they have come a long way to see. Luckily, there is a breach in the wall that sections off the garden from the outside world -- an outside world, crucially, that we are never allowed to see. By the end of page one, the characters we follow for the entirety of the narrative are through the wall and into the garden.

Garden begins with a strong echo of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. A handful of the artist’s humanoid, fashion-forward characters stand assembled before a guard wearing a mask printed with a pattern that encourages the eyes to unfocus, and are denied entrance to the garden that memories of Travel suggest they have come a long way to see. Luckily, there is a breach in the wall that sections off the garden from the outside world -- an outside world, crucially, that we are never allowed to see. By the end of page one, the characters we follow for the entirety of the narrative are through the wall and into the garden.

We will not see them leave. For the rest of the book, the characters negotiate ever more complex and physically demanding man-made topographical features, frequently risking life and limb without a mention of the fact that they are doing so. The dialogue betrays no interiority whatsoever, with completely interchangeable voices alternating between describing the bizarre sights their owners are witnessing and speculating on their purposes and the methods of their creation. Yokoyama’s fanciful setup nails the basic absurdity of modern leisure: the most privileged among us -- the ones with the lives we believe are ideal -- “work” by staring at screens, and “recreate” by climbing mountains.

Garden is more than satire, however, and Yokoyama’s sights are set much higher than the follies of vacationing. The nature of the obstacles his band of wanderers encounter progresses slowly but surely over the course of the book. Waterfalls of simple rubber balls and fountains made of stacked bowls give way to planters made of automobiles and resting areas constructed from airplane parts. Soon the terrain is incorporating giant paper pyramids, a winding maze of irrigation channels that forces its occupants to literally get their feet wet, and motorized blocks of rock that ferry riders up grooves cut into the side of mountains.

Garden is more than satire, however, and Yokoyama’s sights are set much higher than the follies of vacationing. The nature of the obstacles his band of wanderers encounter progresses slowly but surely over the course of the book. Waterfalls of simple rubber balls and fountains made of stacked bowls give way to planters made of automobiles and resting areas constructed from airplane parts. Soon the terrain is incorporating giant paper pyramids, a winding maze of irrigation channels that forces its occupants to literally get their feet wet, and motorized blocks of rock that ferry riders up grooves cut into the side of mountains.

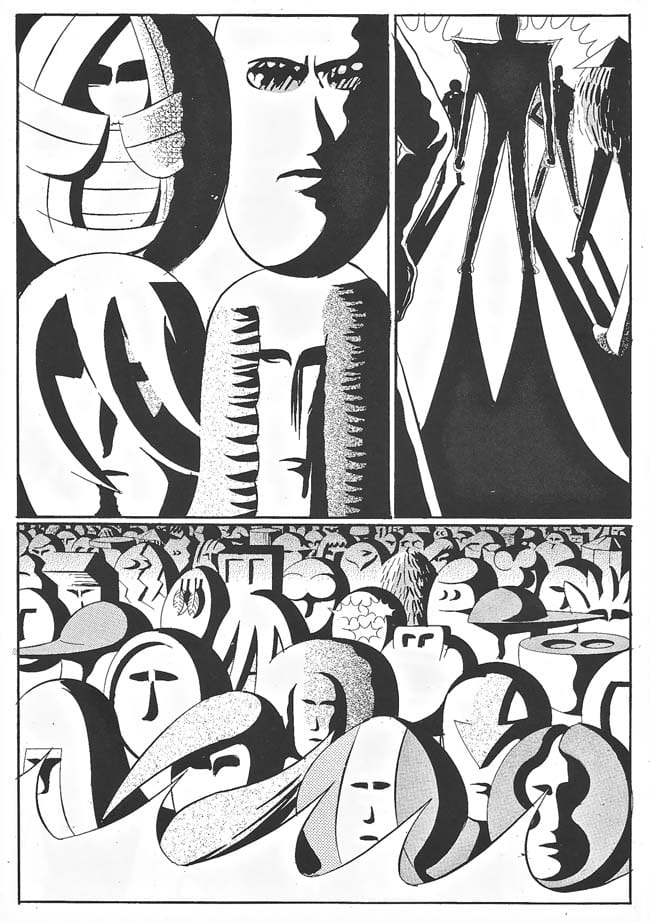

As Yokoyama’s characters move through the vast environment his drawings of them pull back further and further, taking in more and more of both people and landscape. Soon the characters drawn into single panels number in the hundreds, cut off not by any end to their ranks but by the limited size of the pages. And the garden they have broken into is even more endless, if endlessness could be quantified -- swallowing the throngs that surge slowly through it, its entrance the only boundary we ever see. The unreality of death for these characters becomes obvious after a time: they give no pause to paddling across a vast river on thin blocks of some unidentified substance or shimmying across a single bar suspended thousands of feet in the air as waterfalls spray them with mist. Pain seems not to be a factor either: a group tumble down a kilometer-high cliffside is merely a means of getting from one place to another. And one begins to wonder about the relevance of time in the garden after one character mentions that four pages’ worth of firepole descents have taken “over an hour”. Taken together and combined with the miles-wide map the characters piece together from a desert made of aerial surveillance photos, it’s enough to force a deeply fascinating metaphorical reading of Yokoyama’s text. This journey is not one undertaken by individuals, but by humanity as a whole. And wherever the infinite stream of participants came from, it must have been somewhere much smaller than this place. Yokoyama’s garden is no mere repository for plant life. It is the garden of earthly delights, an entire world full of technological constructions as disarmingly bizarre as those in the world around us would seem to someone who had never encountered them before.

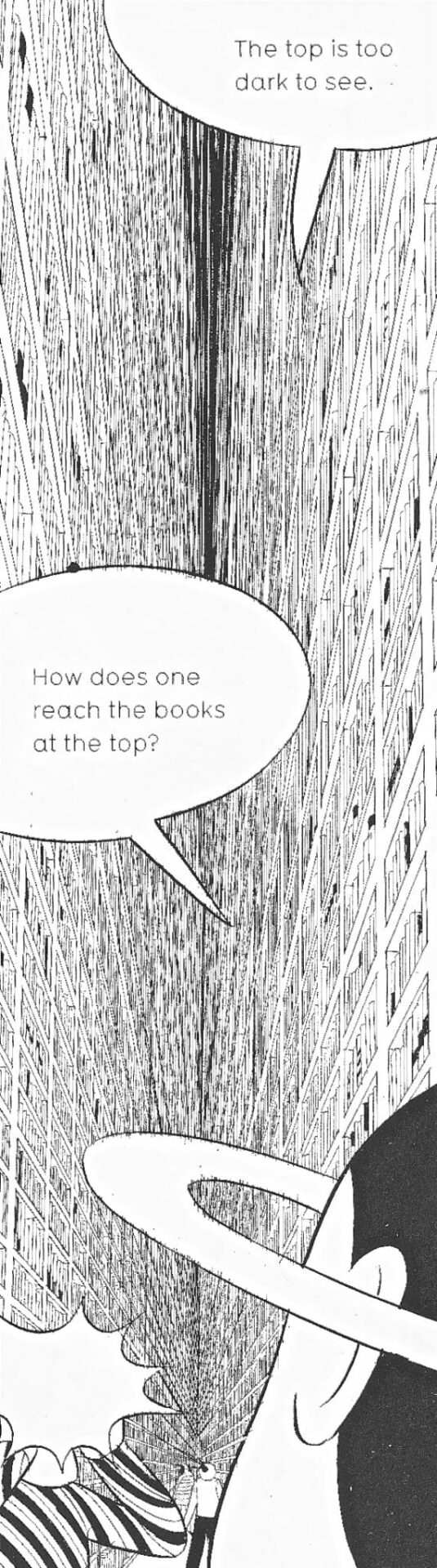

The purpose of this world's existence, however, becomes a more and more engaging question as the complexity of the environment continues to increase. An indoor maze can only be traversed by crawling through sections, and features doors that open into rooms of quicksand and endless chasms. The maze leads into a library full of books closer to the size of skyscrapers than the insubstantial things we’re used to; books that taken together seem to contain a pictorial index of everything in the world. Unseen projectors begin to beam gargantuan images of the characters’ faces onto the travelers as they trudge onward. The total deadpan of Yokoyama’s dialogue, refreshingly funny at first, begins to seem more and more sensical as the book wears on -- given these humbling, ultimately unfathomable surroundings, what else is there to do but describe and wonder? One begins to admire Yokoyama’s characters for their ability to keep up such constant patter; we, after all, read the book and react to its contents in silence.

The purpose of this world's existence, however, becomes a more and more engaging question as the complexity of the environment continues to increase. An indoor maze can only be traversed by crawling through sections, and features doors that open into rooms of quicksand and endless chasms. The maze leads into a library full of books closer to the size of skyscrapers than the insubstantial things we’re used to; books that taken together seem to contain a pictorial index of everything in the world. Unseen projectors begin to beam gargantuan images of the characters’ faces onto the travelers as they trudge onward. The total deadpan of Yokoyama’s dialogue, refreshingly funny at first, begins to seem more and more sensical as the book wears on -- given these humbling, ultimately unfathomable surroundings, what else is there to do but describe and wonder? One begins to admire Yokoyama’s characters for their ability to keep up such constant patter; we, after all, read the book and react to its contents in silence.

The states of passive reception and frequent bafflement put forward by the dialogue, along with the basic story structure of the exploratory journey through wholly unfamiliar climes, invites another reading: that of the drug narrative. Yokoyama’s drawing, often verging on abstraction and full of lines used as much for visual noise as depiction, touches on an unconventional but vivid psychedelia. The tinges of paranoia and surveillance sliding around the edges of the book and its idea-driven plot progression recall William Burroughs and Grant Morrison. Too, the place Yokoyama is pulling his visions from seems to be one completely beyond the world around us, a place of pure and fully-realized hallucination that most minds can only reach with the crutch of chemical additives. But the pinpoint cleanliness of Yokoyama’s black and white graphic design, the architectural logic underpinning his every construction, and the clarity sparkling behind the methodical page layouts that lead the reader through his story at a remarkably even pace all suggest that this work is coming from a place of total lucidity. As the chaos of the characters’ journey beats itself into order, it becomes more and more apparent that Yokoyama’s rational mind is in full control of what is being put on the page.

After navigating a landscape of towering escalators and a strange village in which “there are no normal houses”, the group is driven into a video-viewing room by an obstacle that is impossible to defeat, the fury of nature manifested as a vicious tornado. Here holographic projections quickly restate the journey their viewers have just been on: placid landscapes give way to more technological manmade ones -- but then the bombs begin to fall onto panoramas that stand revealed as the ones we have just moved through. Multiple images are projected on top of one another in streams of random information too fast to make sense of, too overwhelming to be fully described in the reassuring catalog voice that has carried us through the narrative thus far. Volleys of balls begin to fire at bullet force from the walls and ricochet around the room. It’s impossible to turn anything off. The only solution is escape; the blind wrath of the natural world is in the end preferable to a digital environment spiraled out of control and into something that seems very much like malice. As the characters flee from the digitized version of the world they live in, it all becomes clear. The journey we have just seen is our own, from simple tools and playthings through bending the natural world to our purposes, from industrial machinery to a digital landscape that contains more information than can ever be contemplated. And into the hurricane.

It’s such a highly pessimistic meditation on what humanity has created that it’s difficult not to view the characters’ final flight with something like bitterness. And when the thronged mass of all humanity closes the book by filing one by one into a small rock room with a campfire burning in its center, it certainly seems like the conclusion is a hopeless one. Is this really the only solution, a return to the cave? A sacrifice of all the strange beauty that’s brought us this far? The answer turns out to be both yes and no. In the confines of this small, safe space that somehow has enough room in it for everyone, we see two characters touch for the first time, as one asks another who has salvaged a remnant of the technological world -- his camera -- to see some of the pictures he has taken of the place they’ve been forced to stop moving through. Everyone gathers around to see, and the narrative ends with its characters performing their first action that couldn’t be accomplished by mechanized vehicles or robotic probes: standing in company with one another, ready to enjoy the memories brought on by signs that they have been somewhere, that they have done something.

There’s a metafictional reading to be had from this ending, in which the photos constitute the comic we’ve just read, but the real thrill is in seeing the Warholian Yokoyama, who famously declared his intent to delete the emotion from his work, putting forth a quiet, understated kind of humanism that, after the epic journey undertaken to reach it, feels completely earned as a destination.

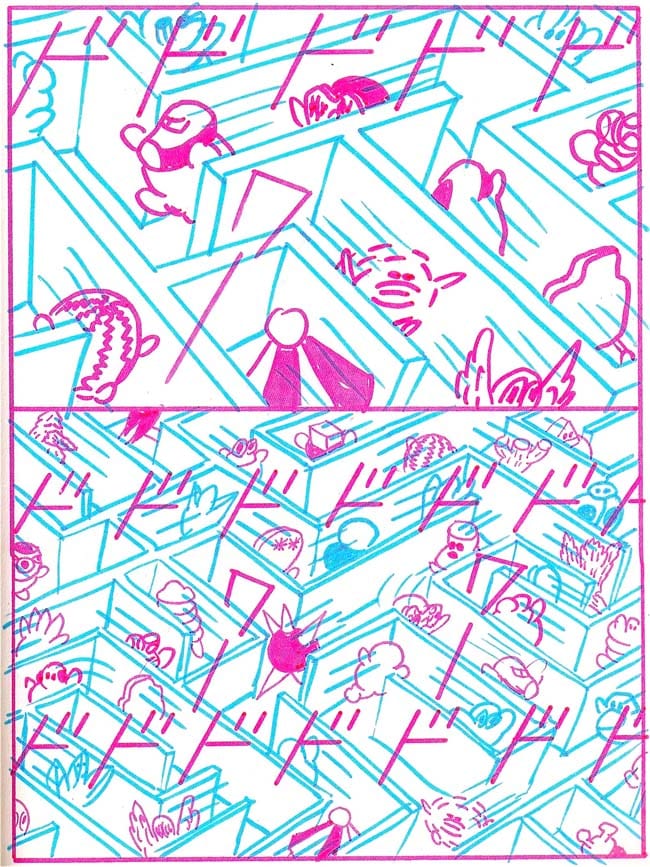

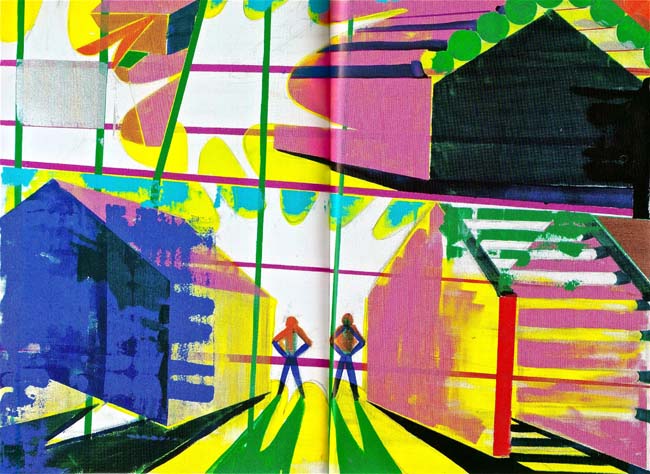

If Garden’s final moment of humanity feels like a considered accession, however, the short works collected in Yokoyama’s next, sadly untranslated book, Baby Boom, constitute a fully committed, passionate embrace. Save for the basic element of enigma that swims over panels that stand up to scrutiny as both figurative and abstract visual information, everything about Yokoyama’s established drawing style has been upended from page one. The immediate shock is that of seeing Yokoyama comics in color: bright and luminous, Baby Boom’s marker-drawn panels have a highly appealing airiness to them, filled with strokes of hue that float against a white background, uninhibited by the pages’ total lack of black space. The artist’s use of his new tool is impressive from the first, with immediately pleasing combinations of two or three tones creating distinct grounds figure-object separations in each panel. There’s an ease of access to every page that’s absent in Yokoyama’s black and white work, no matter whether the eye is engaging the drawings as story or abstraction. These are pictures that pull you in with sheer prettiness.

If Garden’s final moment of humanity feels like a considered accession, however, the short works collected in Yokoyama’s next, sadly untranslated book, Baby Boom, constitute a fully committed, passionate embrace. Save for the basic element of enigma that swims over panels that stand up to scrutiny as both figurative and abstract visual information, everything about Yokoyama’s established drawing style has been upended from page one. The immediate shock is that of seeing Yokoyama comics in color: bright and luminous, Baby Boom’s marker-drawn panels have a highly appealing airiness to them, filled with strokes of hue that float against a white background, uninhibited by the pages’ total lack of black space. The artist’s use of his new tool is impressive from the first, with immediately pleasing combinations of two or three tones creating distinct grounds figure-object separations in each panel. There’s an ease of access to every page that’s absent in Yokoyama’s black and white work, no matter whether the eye is engaging the drawings as story or abstraction. These are pictures that pull you in with sheer prettiness.

Beyond the color, though, the work showcased in Baby Boom turns away from the logical acme that drives Yokoyama’s previous books in favor of something more fleeting, more felt than thought out. Yokoyama has gone back to silent comics here, and except for the lines that lay out the gridded panel borders, there is no evidence of the ruler at play on these pages. The lines that make up Baby Boom embrace the spontaneous imperfections contained in human hands -- thinning and thickening, doubling back and looping over themselves, tracing the impressions of geometric shapes more than actually drafting them, condensing into joyous bits of outright scribble in the shadows and the solid blocks. Even the colored space within the thick marker lines themselves defies uniformity. Here and there it fuzzes out into the white surface of the paper, condenses into a spot of purer color to indicate extra pressure from Yokoyama’s fingertips, or pulls up and gives way to a rough grain where the strokes end. Yokoyama’s lines aren’t the flowing brush trails of Paul Pope or the spiderwebbing coils of Guido Crepax, but they’re as effective a primer in the sensual qualities of comic book artwork. Every line put on the page in Baby Boom is quick and decisive, full of an infectious joy.

It’s an artistic approach that’s perfectly matched to its subject matter, which presents a series of vignettes -- some barely snapshots of moments, others longer meditations on single themes -- centering around the warm, definitively human interactions of two characters. Yokoyama’s character designs leave behind the look of humanity almost completely as a result of Baby Boom’s simplified graphic approach (one resembles a man's body with a head something like a bird’s, the other a dandelion puff or perhaps a baby chick), but it’s impossible not to read the dynamic of father and son into the scenes they share. The bird-headed dad feeds the fluffy kid with a baby bottle; the kid builds a tower out of blocks that the dad helps him finish when it gets too tall; the two clean the house, visit a playground, and go to an open-air market where the dad buys the kid a chewing gum and a soda.

The sense of joy in these sequences is predominant, moreso so than any one picture or idea. Some of the stories are formalist explorations -- an eight-page scene depicting a game of catch between father and son changes color schemes halfway but sticks to a rigid, dense fifteen-panel grid throughout, providing an authoritative object lesson in the dynamics of back-and-forth motion across a page -- while others are almost like drawing journals, consisting of hastily scrawled landscapes whose great virtue is the energy with which they’re drawn, the characters seemingly added in as near-afterthoughts. Occasionally the amount of linework squeezed into a single panel or the alien quality of the ritual being enacted on a page becomes too much, and the eye moves into a different mode of viewing, following lines instead of characters, color relationships instead of panel progression. But it never feels as though we’re missing anything: the spark of life is in these lines regardless of how successfully we're able to piece them together.

The sense of joy in these sequences is predominant, moreso so than any one picture or idea. Some of the stories are formalist explorations -- an eight-page scene depicting a game of catch between father and son changes color schemes halfway but sticks to a rigid, dense fifteen-panel grid throughout, providing an authoritative object lesson in the dynamics of back-and-forth motion across a page -- while others are almost like drawing journals, consisting of hastily scrawled landscapes whose great virtue is the energy with which they’re drawn, the characters seemingly added in as near-afterthoughts. Occasionally the amount of linework squeezed into a single panel or the alien quality of the ritual being enacted on a page becomes too much, and the eye moves into a different mode of viewing, following lines instead of characters, color relationships instead of panel progression. But it never feels as though we’re missing anything: the spark of life is in these lines regardless of how successfully we're able to piece them together.

Through it all the sense of real caring -- even love -- between these beings is so strong that the space between their figures ends up functioning as a visual device in and of itself. The eye can’t help but close the distance between them when they share panel space, and when they don’t we end up wondering where the other one has gone. As content it’s hardly the earth-shaking experimental literature of Garden, but it feels like the only valid point of progression from that work. After taking in the world and humanity as a whole, it seems only right that Yokoyama should narrow his gaze to focus on some of the smaller stories that build the one big one, and in doing so be touched enough by the legitimacy of the emotion that they carry to create a new style for drawing them with. Each of Baby Boom’s stories, no matter how trivial or even banal the events depicted in them are, is bound to pull a smile from all but the stoniest of faces. That the overall idea of the stories here isn’t anything particularly new or individual, doesn't hurt the work at all, and the archetypal quality of the stories ends up a virtue at many points. Baby Boom is a book about how the world is a beautiful place, how living in it can be a very wonderful thing, and how the presence of others is what keeps happiness alive in us.

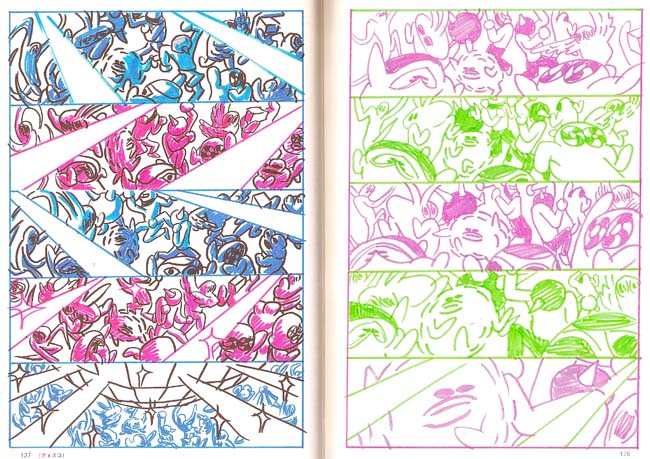

The comic’s standout sequence, however, comes near its end, and it suggests that Yokoyama may cherish what he has found in his exploration of pure humanism, but he is not fully satisfied by it. Six stripped down, backgroundless eight-grid pages of father and son contorting themselves in expressive dance moves beneath the glitter of a disco ball suddenly explode into widescreen, pyrotechnic shots of a huge crowd gyrating beneath strobing spotlights, the color scheme changing violently with every new page, culminating in one of the book’s only two uses of black linework. Two pages later the characters are flying out into the starry embrace of space. It’s about as purely musical as comics have ever gotten, as immediate and propulsive as the bass kicking in under the percussion track on a dance club’s roaring sound system. Yokoyama uses color and a newfound sympathy for characters to bring the human into his comics’ topics of discourse in Baby Boom, but by the time the book finishes it seems like what he really wants to do is cut heads with eye-popping, formalist color comics. Thankfully, in Color Engineering, his most recent release, he does just that -- and with a mastery that few before him have.

Color Engineering opens with an explosion. A four-panel, vertical-orientation page of painted comics, its surface battered to the point of impressionism with white brushstrokes, depicts what the explanatory end notes identify as “a round iron sphere or something” but looks for all the world like a planet orbiting in space slowly breaking apart, ripped asunder by internal force. The following spread is given over to a single painting of the explosion, rendered in violent orange and green and blue and pink, smoke billowing everywhere, chunks of debris flying, brushstrokes gloriously smeared. It’s a note-perfect announcement of intent: this is going to be the most dynamic, brute-force comic you’ve ever seen, but it kills softly, with a master painter’s attention to texture and detail. This, finally, is Yokoyama’s arrival at the idiom of art-comix, of the primary importance of the substance on the page. Color Engineering translates Baby Boom’s affection for the human into a fascination with investigating how much evidence of the human hand at work a piece can bear while still retaining its content.

The exploding planet as beginning, however, also calls back to a very different though no less masterful narrative. The destruction of Krypton, Superman’s cauldron of birth, was the zero point for the creation of what became American comics’ best-known idiom; Color Engineering is Yokoyama’s first book to be released simultaneously in America and Japan. The audacity of the opening pages borders on braggadocio -- here comes the next comic to be as important as that one was, it thunders. And indeed, Color Engineering isn’t entirely unlike superhero comics, if one can see past the marvelous filter of Yokoyama’s stylistic gestures for a moment or two. This is a return to the theme of the artist’s first book, New Engineering, which was mainly concerned with various massive and powerful machines re-terraforming virgin natural environments into constructions presumably designed for some unknown human use. Color Engineering mixes stories that recall Garden into the formula, juxtaposing the machines’ handiwork with the attempts made to understand them by the humans they surround. It all boils down to monolithic, unknowable forces acting on an environment that also contains living inhabitants. But where the prospect was paranoia-inducing -- even out-and-out frightening -- in Garden, here in color and buffered by the unflappable tone of Yokoyama’s dialogue, it feels more like the workings divinity: perhaps unfathomable, but more benign than malicious. In this aspect, Color Engineering is like a superhero comic without any characters, a chronicle of earth-shaking power and its effect on the world around it.

As a thread to follow over the length of an entire book that’s pretty abstract, and rightly so: Yokoyama’s pictures embrace abstraction here like never before, the new medium of paint pushing the comics page toward a new identity as a vividly colored noise container, its panel borders as much a tool for dictating compositional shape and color boundaries as plot pace and moment-to-moment storytelling. Yokoyama’s canvases read like Mark Rothko working over Kirby layouts, amplified and dynamic with massive slabs of color arranged in bracingly graceful relationships to one another. Even on the more conventionally drawn and colored pages, though, Color Engineering follows the logic of painting as much as comics. Every panel is a fully composed unit unto itself, certainly contributing to something greater than the sum of its parts, but more striking on first view as something spectacular in isolation.

As a thread to follow over the length of an entire book that’s pretty abstract, and rightly so: Yokoyama’s pictures embrace abstraction here like never before, the new medium of paint pushing the comics page toward a new identity as a vividly colored noise container, its panel borders as much a tool for dictating compositional shape and color boundaries as plot pace and moment-to-moment storytelling. Yokoyama’s canvases read like Mark Rothko working over Kirby layouts, amplified and dynamic with massive slabs of color arranged in bracingly graceful relationships to one another. Even on the more conventionally drawn and colored pages, though, Color Engineering follows the logic of painting as much as comics. Every panel is a fully composed unit unto itself, certainly contributing to something greater than the sum of its parts, but more striking on first view as something spectacular in isolation.

Yokoyama’s reading of the single panel as canvas astounds again and again, inviting switchups of medium right into the middle of stories, keeping the reader forever on their toes for the next drastic upending of a narrative’s established order. Inked pages colored with marker give way to ones colored in thick gobs of paint before the lines drop out completely, leaving coats of pure color engaged in abstracted spatial relationships with one another before suddenly switching into panels of colored, screentoned linework so precise that they could have come from a technical manual. Eventually even photography works its way into the comics, forcing slightly mundane shots of Japanese countryside and buildings into service as the same assemblages of light and tone the rest of the panels are. The drawings collected here are so tangible, so vivid and full of visual information, that they subjugate pictures of the real world to the status of trompe l’oeil, making readers look for the funhouse-mirror Yokoyama logic in the new frames before realizing that these pictures are in thrall to that other logic, the one outside the book and far away.

Everything in Color Engineering is calculated for maximum visual impact -- the switchups in medium are dictated by overarching rhythms and often serve story purposes, but they’re there to be pieced together later. The real meat of these comics is in surrendering and letting every panel hit with as much force as it can muster, to make the sheet of glass or giant drill from last panel as fresh and astonishing as it was there in this one. And when a double-page spread doesn’t provide enough room for Yokoyama to build to a proper crescendo, it’s solved easily enough by one of the many fold-out pages, which force actual physical action on the reader, demanding we assemble the book in order to be properly blown away by it. If Garden is a book to be read silently, in the stillness of gathering awe, Color Engineering is comics to yell and scream and go dumb in your chair to.

Everything in Color Engineering is calculated for maximum visual impact -- the switchups in medium are dictated by overarching rhythms and often serve story purposes, but they’re there to be pieced together later. The real meat of these comics is in surrendering and letting every panel hit with as much force as it can muster, to make the sheet of glass or giant drill from last panel as fresh and astonishing as it was there in this one. And when a double-page spread doesn’t provide enough room for Yokoyama to build to a proper crescendo, it’s solved easily enough by one of the many fold-out pages, which force actual physical action on the reader, demanding we assemble the book in order to be properly blown away by it. If Garden is a book to be read silently, in the stillness of gathering awe, Color Engineering is comics to yell and scream and go dumb in your chair to.

The book closes with an encyclopedic restatement of its contents: each story re-sequenced from the pyrotechnic, free-flowing layouts that we first read them in to tight, neatly balanced grids. These, apparently, are the comics as they were first designed -- which casts the preceding material in a very different light. The main artistic element of the book is revealed to be its sequencing: the size to which each frame was blown up, the space on the empty spread or fold-out it was put down in, the pace at which it fills the pages. These comics existed, and then their artist used them to make new comics. It’s a final blast of formal genius that trumps all, bringing the focus back around to the element of sequential art contained in these pictures, they way they’re pieced together. Yokoyama is quite plainly putting on a show here, more concerned with the comics medium’s power to scorch earth visually than communicate objective information. The beauty of this material is to be found most of all in whatever unique messages your own eyes pull from its textured canvases, its phased-neon color transitions, the precise individual lines that construct its pictures. It feels an awful lot like a defining statement for art-comix, a contribution of both sheer visual force and statement on form that radiates with a singular brilliance.

Like only a few before him, all of whom are enshrined in whatever underwhelming immortality comics is capable of giving them, Yokoyama is making work so far ahead of the curve that it’s hard to know what to do with it. The very idea of Yokoyama rip-off comics seems laughable: this is and always has been content that couldn’t possibly be divorced from the beautiful lines that create it, and vice versa. It seems unlikely indeed that stories about giant machines and uninformed architectural criticism will become the next catching thing in comics, and while there are plenty of artists working the line between canvas and cartoon or figuration and abstraction, none are doing it with such elevated skill or such intelligence of theory. With his last three books Yokoyama has pulled off a triumph of lit-comics, a triumph of art-comix, and an achingly gorgeous thing that sits somewhere in between. As with all great works, the only answer is probably to let their effect on the form work itself out. Truly special work, after all, only elevates its medium. Yokoyama has given us three pieces of art that are very special indeed, and it seems to me that the only reaction worth actively pursuing is to read them.