One of mainstream comics’ finest writers, John Stanley was also among its most prolific. He was fortunate to be in the employ of Oskar Lebeck, whose Western Publications created the editorial content for all the Dell comic books, from 1943 through 1961.

Western specialized in licensed properties. Western’s versions of these mass-media entities were often vastly re-imagined/bulldozed by their anonymous adapters. Carl Barks rethought Walt Disney’s bellicose Donald Duck as a multi-layered everyman besieged with mundane traumas. John Stanley made Walter Lantz’ strident Woody Woodpecker a bittersweet drifter, at the edge (and at the whims of) society. This montage of panels (most drawn by Stanley) offer a taster of his world-weary Woody:

In 1945, Stanley received the defining property of his career. Marge Buell licensed her pantomime gag cartoon, Little Lulu, a well-loved feature of the Saturday Evening Post, to Western. Stanley’s version, which bore less resemblance to Marge’s in each of his thousands of stories, wasn’t the feature’s first mass-media adaptation. New York-based Famous Studios began a series of Lulu animated shorts in 1943. The cartoon series ran through 1948, in tandem with Stanley’s rapidly developing (and dis-similar) comic book version.

Little Lulu, which Stanley would helm for 14 years, and write close to 10,000 pages of story, became one of America’s top-selling periodicals. Most comics careers might have been wholly—and comfortably—built around this steady, high-profile gig. Stanley continued his earlier series, picked up new features, and created two original strips by the close of the 1940s.

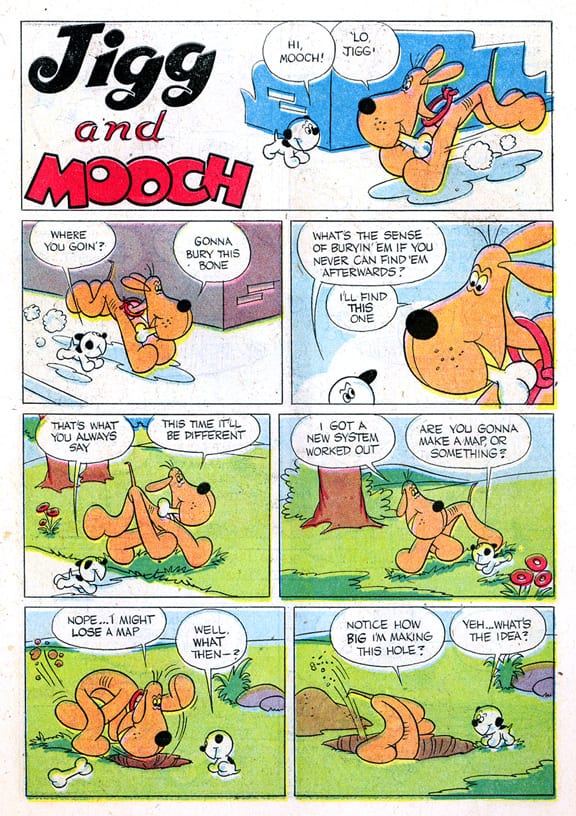

Neither “Jigg and Mooch” or “Peterkin Pottle” survived a year. Both were ambitious, graphically inventive features that didn't last long enough to find their sweet spot. Stanley was a slow-burner, and took a year or two to break in a new strip, find and define its world, and set its pace.

If Stanley—who’d had the prestige of a 1947 cartoon in The New Yorker—was discouraged by the failure of his first original strips, it didn’t show in his work. Lulu entered its most robust period in 1949, and remained high-functioning for several more years.

In the research for my three-volume bibliography of John Stanley’s comics work (which is available on CreateSpace and amazon), the ‘50s was the most problematic period. It’s surprising how prolific Stanley was in that decade. His Lulu work—which soon included a satellite title, Tubby—is a staggering aggregate. Each year he wrote, in storyboard form, a dozen 36-to-52-page monthlies, four quarterly Tubbys, and, from 1955 to ’58, one or two 100-page annuals.

This work is built on a series of story formulas. After 1954, the formulas become more mechanical, and thus more obvious. Like George Herriman, John Stanley had the skill and wit to milk a set of stock scenarios for every possible (and impossible) variation. By 1951, Stanley knew the Lulu cast so well he could spin these stories seemingly without effort.

In the high-performance vehicle of Lulu, Stanley’s fail-safes guaranteed finesse by clockwork. At best, Stanley simply picked one of his formulae, did a mix-and-match of characters and narrative stakes, and had a likable, amusing story. At worst, late in the Lulu game and through much of his subsequent work on Nancy and Sluggo, Stanley seems exhausted of joy but determined to soldier on.

A lifelong sufferer of depression, in the pre-Prozac days when self-medication, via tobacco and booze, was a daily norm, Stanley was as much workaholic as alcoholic.

In his non-Lulu 1950s comics, Stanley tests untried concepts, characters and theories. The best of this material presages Stanley’s auteur comics of the 1960s, Thirteen Going on Eighteen and Melvin Monster. It shows that Stanley had the first inklings of his finest ideas while Truman was in the White House—comedic notions Lulu couldn’t accommodate.

The worst shows the raw edges of Stanley the pro-workaholic. Given lackluster characters about whom he didn’t give a damn, Stanley phoned his work in, or wrote cynically, without the TLC he accorded Lulu as late as ’55. These lesser stories often feel like the late films of director Edward L. Cahn, a once-prestigious filmmaker who made harsh, minimal genre films in the last decade of his life. Cahn tackled any saleable genre—horror, teen, Western, crime—with the same steady but detached hand. His dispassionate burnout becomes part of these fascinating, barren films.

This might be an unfair analogy. Stanley didn’t helm a large crew. He created stories alone, and sent them to his editors at Western. They were handed off to artists that he seldom—if ever—met in person. Irving Tripp, artist of the bulk of Stanley’s Lulu stories, only saw Stanley a handful of times during their shared tenure. Working in isolation, Stanley confronted inspiration and frustration without an audience. By the time a story saw print, he and his collaborators were long gone.

Every mainstream comics writer of the era faced burnout. Stories were written to fit space, hew formulas or fill pages as needed. Most comic book authors lacked Stanley’s luxury of the developed, finessed world of Lulu or Tubby. The best they could hope for was job security in an increasingly uncertain market.

Only a handful of comics creators could afford to love their work. Some, like Harvey Kurtzman, paid a high price—hospitalization due to overwork. The ephemeral nature of the comic book, and a growing social adversity to the form, was enough to make most pros cynical.

A love-hate relationship with comics informs John Stanley’s work of the 1950s. Stanley’s involvement in his work ranges from rapture to repulsion—often within the pages of a single comic book. After 1955, this attitude infects Lulu. Characters shout at one another, at top volume, and the stories’ comedy is more often based on their suffering through adverse, merciless situations.

Before exhaustion set in, Stanley produced some first-rate, little-known work outside the margins of Little Lulu. Because he was never allowed to sign his work, it’s taken effort to ferret out these stories. Stanley’s visual and verbal quirks serve as a tacit by-line to hundreds of innominate pieces.

In 1950, Stanley began two titles based on live-action film and television entities. The first, Howdy Doody, exemplifies Stanley-the-hack. He never found a way to make these mega-popular TV characters work within his sensibilities. After the first issue, his disdain is evident. The only characters he finds of interest are the mute clown, Clarabell, and the freakish outsider-being, Flub-a-Dub.

Flub was right up Stanley’s alley—the agitated outsider who constantly seeks to bolster his low social status. This figure, while worried about what others think about him, holds himself in high regard. This is the core figure of John Stanley’s comics.

Stanley’s Howdy Doody work reads as if the property’s owners looked over his shoulder as he wrote. Its lack of joy is wearisome.

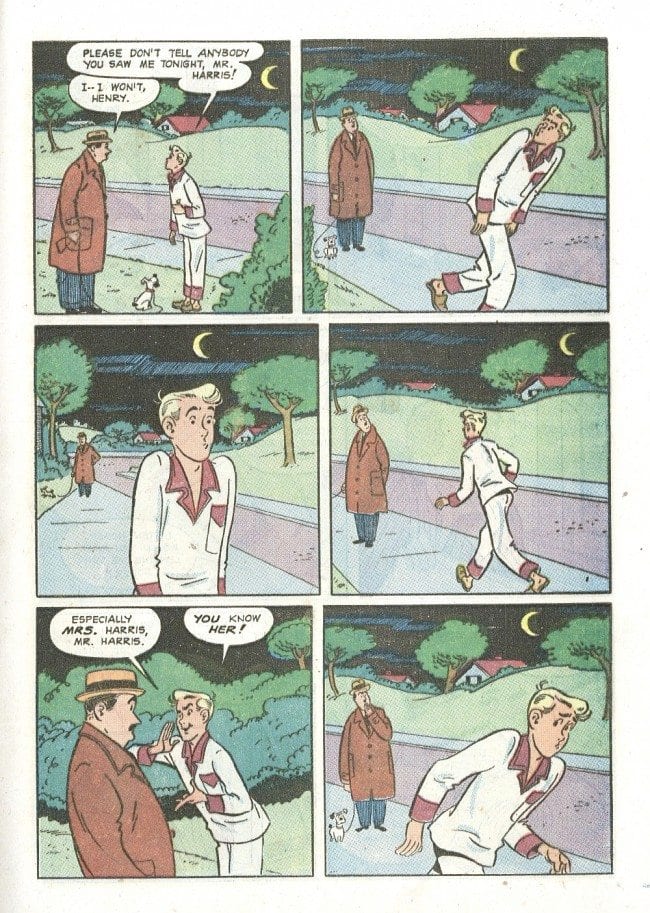

The more low-key Henry Aldrich inspired better from Stanley. It paired him, for the first time, with his finest collaborator, the talented and expressive cartoonist Bill Williams. After seven years of writing stories about children and childlike characters, Stanley was without doubt pleased to depict humorous, sympathetic adult and high-school figures.

Story length was liquid in Henry Aldrich. Each piece could run as long or short as Stanley’s whims dictated, as long as those 52 pages were filled. In earlier Little Lulus, Stanley wrote several longer stories, but as its formats locked in, the book settled into a dependable menu of story numbers and spans.

The gem of Stanley’s Aldrich stories—and one of the peak moments of his career—is a 31-page narrative of nightmarish escalation, published in the book’s fourth issue. Henry and his best friend, Homer Brown, are faced with a potential perfect storm of social embarrassment. Henry’s mother dispatches them to take her dressmaker’s dummy over to a friend’s house. What might be a swift task becomes a waking hell, because Henry (and then Homer) care about what others think—or what they think others will think.

Henry seals his fate with a melodramatic complaint: “Oh, MOTHER! Can you IMAGINE what people will think when they see me lugging this thing…” Homer shares his pal’s shame, and suggests covering the dummy with a blanket. Through a breathless series of events, the boys become suspected of murder. The story’s climax is a large panel in which the beloved teen characters (and Henry’s mother) are cornered by 17 armed policemen—an event no corporate rights holder would allow today.

Though this black-humored escalation is clever, it’s not just a sitcom. Stanley throws the reader off the scent with small moments that further define the characters. Homer and Henry have a recurring conversation about Homer’s ill-advised use of cider vinegar in a punch drink for a party. This topic bobs to the story’s surface at random intervals, against the grain of the narrative, in a credible way.

Stanley had a great ear for dialogue—a constant asset of his 1950s work. His comfort with vernacular, phonetic spelling and unerring usage of the ellipse makes the chat in these stories novelistic.

The story veers into a zany sitcom set-piece that, for 10 of its 31 pages, recedes the main drive of the narrative—that Homer and Henry are wanted by the law for murder. At some point, in this interlude, the story’s original path seems lost. When it returns, at full force, in a climax worthy of Preston Sturges, it’s inevitable and surprising.

This story is an aftershock of a six-page piece in a 1949 issue of Little Lulu, in which Tubby is desperate to not lose face by wheeling his mother’s dummy through the neighborhood.

At five times its length, and with a pair of socially awkward adolescent boys, the Aldrich version suggests a richness in Stanley’s observational comedy that the shorter pieces of Lulu could not contain. If graphic novels were an option in mid-century America, Stanley was one of the few creators capable of sustaining reader interest at such length.

Stanley’s Henry Aldrich run climaxes with a trilogy of “Homer Brown” backup stories, in issues 6-8. To see his girlfriend Agnes, Homer must endure the mind-games of her little brother, Edgar. A true sociopath, Edgar is ten times Homer’s match, and forces the gangly boy-next-door through a series of personal humiliations—from which the kid profits.

In the last of the three stories, Edgar preys on Homer’s romantic insecurity. He hires Edgar to report anytime he sees Agnes with another man. Mindful of his weak status, Edgar offers a bland warning: “Keep in mind that I have a slight WEIGHT advantage over you!”

Oblivious to Homer’s—or anyone’s—feelings, Edgar strives to earn that dime. When a portly, balding middle-aged man shows up to take Agnes away, the kid roller-skates to Homer’s home, demands payment, and then lays a devastating account on the teen. Homer’s reactions, and Edgar’s subsequent brag to a colleague, are priceless:

Homer can’t keep himself from accosting this alleged Lothario, and receives a public humiliation from his cross girlfriend. The story ends with Homer imagining Edgar boiling in a cauldron of oil, his face wrenched in suffering. To schlubs like Homer, a thought balloon is as close as they’ll ever get to revenge.

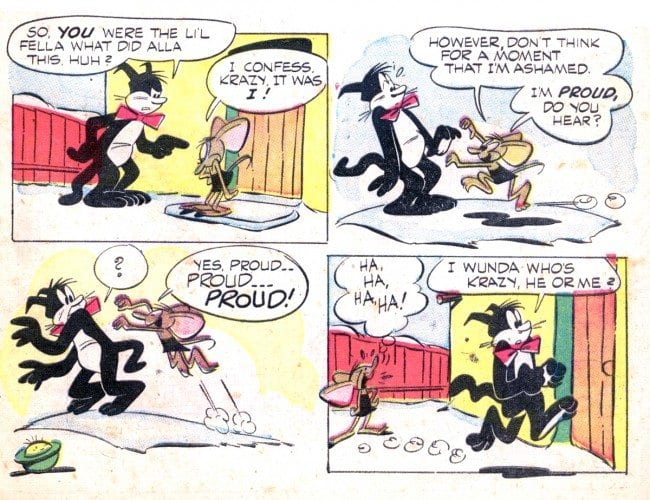

In 1951, Stanley took on an unusual, controversial new assignment—George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. The original strip ended with its creator’s 1944 death. At that time, it was a shadow of the inscrutable strip that wowed an intellectual cult audience in the 1920s and ‘30s. Why it was thought fit for a comic book revival, seven years hence, is lost to time.

Perhaps Stanley was a fan, and lobbied for this revival. His best work shares, with Herriman’s, a love of linguistics and faith in inviolable formulae. The comic book version retains some of the Herriman visual/verbal whimsy, but re-designs the characters in a Hollywood animation style.

Stanley struggles to make something of this reboot over the comic’s initial five-issue run. He keeps the triangle of Krazy, Ignatz Mouse and Offisa Pupp, and imbues each of these central figures with new personality quirks. Krazy is joyfully aware of his stupidity; Pupp becomes as agitated and fussy as Lulu’s truant officer, McNabbem.

Ignatz is Stanley’s clear favorite. Like Tubby and many other similar characters, he’s on the fringes of his culture, convinced his anti-social behavior is right and doomed to cycle through the same bad decisions that shatter any attempt to improve his status.

At its best, Stanley’s Krazy is a playful, fairly reverent update of the Herriman original. At worst, it overwhelms the reader with aggressive, frenzied slapstick and new characters that don’t mesh with the principals.

Stanley returned to Krazy for another five issues from 1953 to ’56. No one story stands out from the 360 pages of material he produced. A reading of these comics, in juxtaposition with his contemporary work on the Lulu series, as his patience with that series slowly eroded, is both rewarding and saddening.

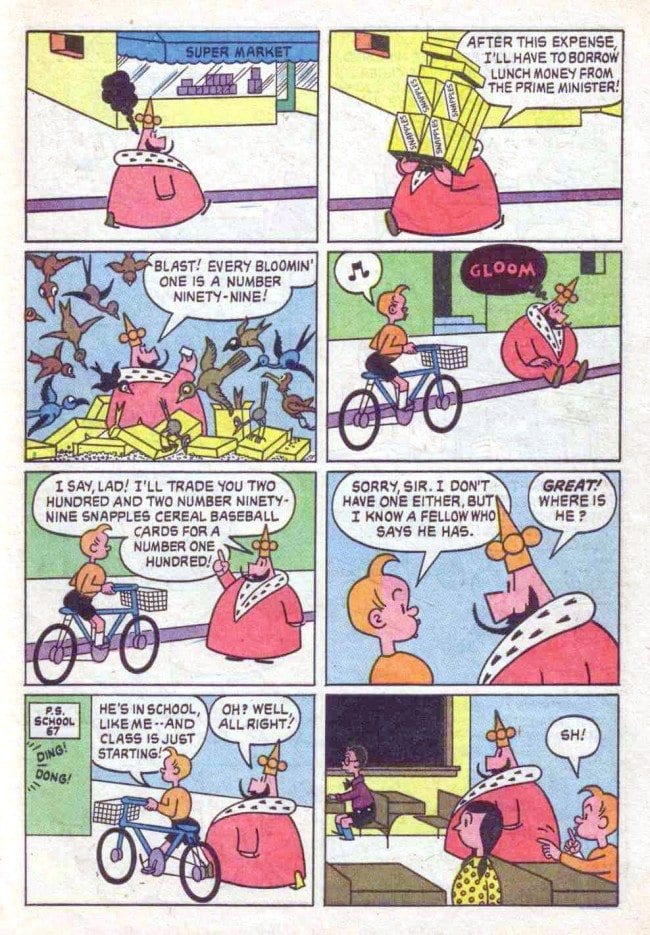

More fruitful is Stanley’s three-issue take on O. Soglow’s elegant pantomime, The Little King. Imagine Tubby as an adult: in a position of power to which he is irritable and unwilling, his mind on simpler, less mature affairs. Stanley got his variation on Soglow right from the first story, and made one significant change. His King speaks—and is overly fond of his own voice.

In Stanley’s first story, an untitled, 22-page freeform narrative, the King abdicates his throne, weary of the endless paperwork and politics. Before this, he befriends Kit, a little boy who shares his interest in fun and frolic. King takes kite-flying Kit under his wing, and soon declares him sovereign. Dressed as a hobo, the ex-ruler is immediately jailed for vagrancy, as his successor declares strawberry jelly-beans the new currency of the realm.

Meanwhile, a terrorist clique attempts to bomb their way into the royal vaults. The exchange of candy for gold renders their efforts moot.

King reclaims the throne, which is fine with Kit, who’s late for lunch. Order sort-of restored, the King wistfully bids Kit adieu. His position is inescapable.

Stanley’s finest “Little King” story is “The Search,” the last piece he wrote for the series. The King is obsessed by Snapples, a breakfast cereal with a baseball card in each box. His goal is to complete the set of 100, which entitles him to a free baseball cap and a ticket to “the big game today.”

Despite the urgings of his staff, the King escapes the castle and mingles among the commoners. He buys out a supermarket’s stock of Snapples, but the one card he needs eludes him. He infiltrates a grade-school class to see this goal to completion, and earns the scorn of a humorless teacher.

By sheer whim of fate, the King gains the missing card, but realizes that his official duties call on him to commence the ball game. King gives his prize to a Kit-like boy, who sits with him at the stadium and, in the last panel, wears the King’s gold crown.

Like cartoon director Tex Avery, Stanley shunned sentimental happy endings in most of his work. When he does express sentiment, it’s disarming and it usually works. But regardless of its happy ending, it’s the King’s willingness to sacrifice high status and dignity for a baseball card—and his dogged pursuit of this trivial gain—that makes “The Search” one of Stanley’s finest unknown works.

Stanley began his comics career as a cartoonist, and struggled to keep his hand in the craft as writing demanded more of his time and attention. He returned to cartooning in 1951, when he drew the balance of the 31st issue of Little Lulu, perhaps due to deadline problems.

His most focused cartooning of the ‘50s occurs in eight issues of the spin-off Tubby title. Stanley drew the first few Lulu one-shots in 1945 and ’46, and his struggle to adapt to the primitive style of Marge Buell had a negative impact on his work for a few years.

His Tubby art, while burdened by that need to make like Marge, supported a series of intense book-length narratives, in which Tub is often in a position of true threat. These stories made room for the darker edge of Stanley’s imagination, which seldom found a berth in Little Lulu.

The last few Stanley-drawn Tubbys revert to self-contained short stories, as his cartooning grows more comfortable, bold and expressive. Stanley’s single finest story, “The Guest in the Ghost Hotel,” which appears in the seventh Tubby, blurs fantasy and comic-book reality with a gorgeous ambiguity. Like the epic-length Henry Aldrich story of 1951, “Guest” begins benignly, and its turn into playful gothic horror is a genuine surprise.

This piece was featured in Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly’s Toon Treasury of Classic Children’s Comics, alongside other great pieces by Stanley, Barks, Walt Kelly and Sheldon Mayer.

The 1950s ended with Stanley at a nadir of inspiration. His last year of Little Lulu and Tubby reads as if created by a room-size IBM computer, after sufficient data input. Small moments of clarity and joy emerge in these pieces, but they lack the soul and caritas that made the series once transcendent.

John Stanley needed something else to write—some genre that could restore his quick wit and impulsive narrative skill. He wasn’t given that with Nancy and Sluggo, which, in its two years, veers from brilliance to brutality. He had the skills to invent new characters—Oona Goosepimple, McOnion—that he leant on when inspiration failed him.

The hard, shrill edge of the series’ comedy would be revisited, with greater finesse, in John Stanley’s second coming of the 1960s. The put-upon drudge of 1959 had no idea that, in two years’ time, he would be given carte blanche to create innovative new series for Dell comics.

That brittle sensibility remained in his work, but in the service of characters, settings and situations which Stanley created from scratch. By 1963, he would write and draw his comics, and, a year later, sign them. A more informed study of his 1950s work shows that this new path was quietly blazed in hundreds of unsigned, obscure comic book pages.