My first thought was to say that PS Magazine: The Best of Preventive Maintenance Monthly (Abrams Comicarts) is an essential book for any serious Will Eisner fan, but it would be more accurate to say that how essential you find it will depend on how serious a Will Eisner fan you are. Clearly, the disinterested reader would find little of interest in a collection of maintenance tips for antique military equipment. It would be hard to imagine an eye that would not be glazed over by such tidbits as "You'd better hang on to Light, head, service assy G251-7765212 if you've got a 155-mm SP howitzer M44 (T194). It won't exhaust to G260-7419686 light." But the enthusiast who's been nurturing a curiosity about Eisner's lost years will find all he needs to know from this beautifully produced little volume. In 1951 Eisner heard the siren call of the cost-plus contract and took over the visual design of PS, a monthly digest-sized magazine supplement to the Army's formal maintenance manuals. Shutting down the Spirit newspaper section the next year, he fell into the State and hunched in its belly until 1971. In its less exalted sphere it was an artistic disappearing act comparable to Herman Melville's self-exile to the customs house or J.D. Salinger's permanent "Do Not Disturb" sign. That is, unless you were drafted, in which case there was your old Uncle Will explaining in pictures the proper way to overload a truck.

My first thought was to say that PS Magazine: The Best of Preventive Maintenance Monthly (Abrams Comicarts) is an essential book for any serious Will Eisner fan, but it would be more accurate to say that how essential you find it will depend on how serious a Will Eisner fan you are. Clearly, the disinterested reader would find little of interest in a collection of maintenance tips for antique military equipment. It would be hard to imagine an eye that would not be glazed over by such tidbits as "You'd better hang on to Light, head, service assy G251-7765212 if you've got a 155-mm SP howitzer M44 (T194). It won't exhaust to G260-7419686 light." But the enthusiast who's been nurturing a curiosity about Eisner's lost years will find all he needs to know from this beautifully produced little volume. In 1951 Eisner heard the siren call of the cost-plus contract and took over the visual design of PS, a monthly digest-sized magazine supplement to the Army's formal maintenance manuals. Shutting down the Spirit newspaper section the next year, he fell into the State and hunched in its belly until 1971. In its less exalted sphere it was an artistic disappearing act comparable to Herman Melville's self-exile to the customs house or J.D. Salinger's permanent "Do Not Disturb" sign. That is, unless you were drafted, in which case there was your old Uncle Will explaining in pictures the proper way to overload a truck.

The timing of Eisner's decision to seal the crypt at Wildwood Cemetery raises an interesting question of exactly what writing he saw on the wall. It would probably be far less interesting if some killjoy with direct knowledge revealed the utterly mundane answer, so let us stick to the romantic myopia of ignorant speculation. In 1952 the great comic book pogrom was in its recess between the wind and the whirlwind, and those who thought wishfully. An observer as canny as Eisner might have felt differently. The climate for comical colored sidekicks had been getting progressively chillier, and would soon freeze over. The syndicate had cut the size of the Spirit supplement, and it would have been hard see how this trend was going to reverse itself. The usual explanation is Eisner's desire to explore the educational potential of comics, and many who say that are probably in a position to know. It seems to me that what PS represented was something Eisner pursued throughout his career, the opportunity to create comics for an adult readership. Indeed, during most of its run it must have been nearly the only such opportunity in the comic book format outside of Little Annie Fanny, and as such is another tribute to Eisner's savvy.

PS was essentially an experiment in getting people to read the instructions. Most of its pages were a kind of Hints from Heloise if Heloise had been a Valkyrie. The graphic elements of these pages are limited to witty spot illustrations. The heart of each issue creatively and physically was Joe Dope, a color comic book feature humorously illustrating a principle of preventive maintenance of military equipment. These represent the bulk of the collection at hand. These stories were built around a set of characters, several of which were handed down to Eisner from earlier versions of the magazine. These included Sergeant Half Mast, voice of authority and experience, Connie Rod, a pin-up girl in uniform, who demonstrates you don't have to be fully clothed to perform proper maintenance, Joe Dope, a negative counter-example, and Private Fosgnoff, an even more negative counter-example (Joe Dope learns, Fosgnoff never learns).

So, you may ask, beyond satisfying one's curiosity as to what Eisner was up to all those years, what entertainment value does it have? That which combines instruction with entertainment is by definition adulterated entertainment. Well, it's not going to leave anyone clamoring to read The Complete Joe Dope (though you can -- the entire Eisner run of the magazine is archived online at Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries Digital Collections), but there's more than enough to keep the reader engaged through the 250-odd pages of the Abrams collection. The book itself is a lovely little thing, beautifully reproduced from the magazine pages in their original size and looking quite well on coated stock. Neil Egan designed, and Eddie Campbell selected the contents and provides a highly informative historical essay from which I crib without scruple. This is still very much the Will Eisner of The Spirit, much more so than the graphic novels. This has something to do with chronology, but one soon realizes that the Eisner of The Spirit was Eisner with the collaboration of others, whereas the graphic novels are Eisner alone. What Joe Dope demonstrates is that Eisner was an accomplished humorous cartoonist as well as an adventure one. This is a proposition that was put into doubt by the dubious gag cartoon books he produced in the '70s. Beyond that, there is always something interesting about technical expertise, at least for a while. This is particularly so in the Korean War-era strips. The United States had demobilized rapidly after World War II, and so it went to war in Korea with old and sometimes inadequate equipment. They were even flying Mustangs for a while until the MiGs talked them out of it. This must have been the time PS Magazine came most in handy, informing the troops on the unorthodox procedures of making do and scrounging.

As the wartime army became peacetime the military authorities came to find certain of Eisner's methods unsound. In particular they came to believe negative counterexamples were unbecoming to the dignity of the armed forces. Fosgnoff was summarily discharged, and Joe became less of a dope and more of a fellow with the dope. In the best of times Eisner could never be a truth-to-power voice of the soldier like a Bill Mauldin. He was a civilian contractor communicating the wishes of the upper echelon to the lower ranks. As time passed Eisner's grasp on the point of view of the contemporary soldier slipped. Later installments show him attempting to work in bits of contemporary slang, which comes off as convincing as when your teacher tries to do it. Connie Rodd had to be a lesser enticement in an age where a soldier could buy Playboy at the PX, though she maintained her eye candy role to the end of Eisner's run. By that time PS must have seemed like Bob Hope's later USO shows, a relic of your father's Army, appreciated for trying, perhaps, but an anachronism. Worse than that, actually – Hope could use topical humor. (I recall a line of his bout neutral Laos – pronounced "Louse" – shipping neutral ammunition over the neutral Ho Chi Minh Trail that seemed to go over pretty well.)

As to what extent Eisner's PS demonstrates the usefulness of comic strips as an educational tool, I am left skeptical. On the one hand we are assured that the Army's tests showed PS to be more effective than other types of training materials On the other, I look back on my life, which is longer than yours, and I consider how frequently I've encountered comic strips and comic books for educational purposes, which is "in-". In my experience when they are used informationally at all it's for the purposes of advertisement or something one step removed from advertisement. The medium would have to be extraordinarily efficacious to overcome the several layers of resistance it would find. The schools historically tended to consider them the sort of thing they are trying to overcome. Outside of the untranslated and untouched copies of Asterix you would see in French class, the only place you saw them in school in my day was in the drawer of the teacher who had confiscated them. Give someone a comic book instead of a textbook or manual and he's likely to infer you're telling him he's too stupid for a regular textbook. In the Army, on the other hand, if they tell you you're going to get your technical information from a comic book then you're going to get your technical information out of a comic book. Using a comic book for training purposes in 1951 was like using video games for training purposes today (and they do). Back then comics were something everyone had read a lot of; now they are something everyone has read, but not a lot. I would be hard pressed to say from the examples offered here that comics imparted any extraordinarily great amount of information. It seems to me that Eisner explains the key to the effectiveness of PS in a line Campbell quotes: "Whereas the government issue manuals would say 'Remove all sedimentary deposits from the combustion area,' I would say something like 'Scrape the crud off the engine.'" It was less a matter using comics than using English.

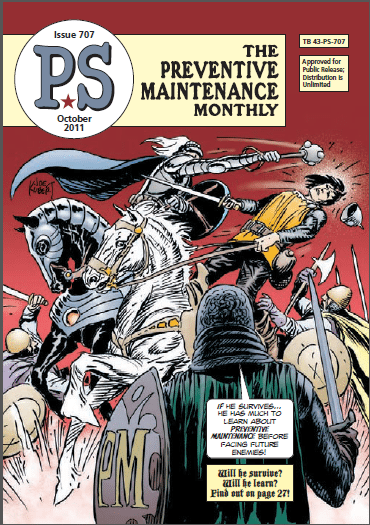

Whether due to effectiveness or organizational inertia, PS continues to this day, more or less along the lines Eisner laid out 60 years ago, and like the Eisner version you're free to look at it online. Sergeant Half Mast is still there, much as before, and so is Connie Rodd, now looking less like the soldier's dream bunkmate than a young suburban housewife in a newspaper advertisement for kitchen appliances circa 1973. She also has an African American doppelganger whose name I didn't catch. (Aretha Rodd, maybe? There doesn't seem to be a Consuela Rodd, though.) In the September issue they even had a return visit from Joe Dope, perhaps as a nod to this book. There is still a color comic section in the middle, presently drawn by Joe Kubert, believe it or not. It's a little like Our Army at War and No Fooling. What is almost completely missing is Eisner's flair. The best description of the predominant graphic style would be "Clip Art." The humor, such as it is, runs heavily to anthropomorphic vehicles looking sickly when they're out of repair. The main comic section is primarily a pep talk for the concept of preventive maintenance, with little attempt to illustrate actual maintenance procedures that I could see. There is also very little to suggest that there are two wars going on. You'd think it's a sore subject that they don't want to discuss in front of the children.

Whether due to effectiveness or organizational inertia, PS continues to this day, more or less along the lines Eisner laid out 60 years ago, and like the Eisner version you're free to look at it online. Sergeant Half Mast is still there, much as before, and so is Connie Rodd, now looking less like the soldier's dream bunkmate than a young suburban housewife in a newspaper advertisement for kitchen appliances circa 1973. She also has an African American doppelganger whose name I didn't catch. (Aretha Rodd, maybe? There doesn't seem to be a Consuela Rodd, though.) In the September issue they even had a return visit from Joe Dope, perhaps as a nod to this book. There is still a color comic section in the middle, presently drawn by Joe Kubert, believe it or not. It's a little like Our Army at War and No Fooling. What is almost completely missing is Eisner's flair. The best description of the predominant graphic style would be "Clip Art." The humor, such as it is, runs heavily to anthropomorphic vehicles looking sickly when they're out of repair. The main comic section is primarily a pep talk for the concept of preventive maintenance, with little attempt to illustrate actual maintenance procedures that I could see. There is also very little to suggest that there are two wars going on. You'd think it's a sore subject that they don't want to discuss in front of the children.