Your stories often have a very strong leftist political bent to them. Do you consider yourself to be a Marxist?

It’s complicated. I’m not a Marxist in any traditional sense. Not in the Marxist Stalinist sense, for sure. I have read a bunch of Marx, and I have read a bunch of other communist thinkers, or thinkers that are sympathetic to communism. Politically, I’m very much to the left of the spectrum in America. But at the same time, I do think that markets actually work. Not in the traditional Republican way, where everything needs to be a market. I think there’s definitely a place for markets where they work very well, but there’s also a place for “the state” to provide certain conditions for that market to work. I think economics should be less about — An economic policy needs to serve the population, rather than the other way around: population serving an economic system. I don’t know if that makes me a Marxist, or not. I definitely have very left-leaning ideas about stuff in general.

I don’t really care except it’s interesting. I’m not trying to cross-examine you. [Laughs.]

Yeah, I know, I’m not trying to defend myself either. [Laughter.] I could be a Marxist.

"Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?"

I had to answer that question when I became a citizen.

Really? When did you become a citizen?

I have dual citizenship, Polish and American citizenship.

Did you do that when you were younger, or was that a recent development?

No, when I turned 18, or 19 — I can’t remember exactly. I was eligible pretty much at that point, and I just became a citizen. It made a lot of things a lot easier, so I did it. It just seemed like the obvious thing to do at the time. I was like, “Oh yeah, it’s been five years; I can be a citizen now. This is what I should be doing.”

Like getting your driver’s license.

Exactly. So yeah, I’m a citizen, and I had to answer that question.

Were they hard questions, in general? For the citizenship test?

No, they were basic civic studies type questions. I think there were maybe some questions about presidents, some Bill of Rights questions, and the communist question. [Laughter.] It was really simple. I remember it being way easier that I ever thought it would be. I just don’t remember specifics. I was nervous. I remember being nervous, but it was a lot easier than I thought it would be.

Was it weird working in advertising, with your political beliefs?

Not really. You're in the heart of a propaganda machine, but it didn't seem to affect me in a day-to-day way. I worked with a lot of people who were ... not as left-wing as me, maybe, but there were also some people that were much more activist than me. I’m not that much of an activist. I'm much more of the armchair philosopher type. [Laughter.] There were definitely people who were much more right-leaning, but I’m the kind of person — I just love debating that stuff, so I don’t care if they say something I don’t agree with; I’m happy to take them up on it and debate away. It was never a huge problem for me, politically, as long as the other person is willing to go along and argue. I have no problem with it. They can keep their crazy ideas, but as long as they're willing to debate them, I’m fine. [Laughter.]

Some people can’t handle that.

Yeah, I know. And there were people I remember. We had this little quad; it was four of us, and one of the people was my boss, who was much, much more right-leaning, and there was this woman who was there, and whenever we started going at it, she was just like, “God, I’m out of here. I can’t listen to this any more.” But I enjoyed that. I enjoy the debate, and getting into those kinds of arguments.

Your stories show an obvious interest in science fiction, futurism, utopias, that kind of stuff, but also in ancient history, ancient architecture, and invented fake history. Fake pasts as well as fake futures.

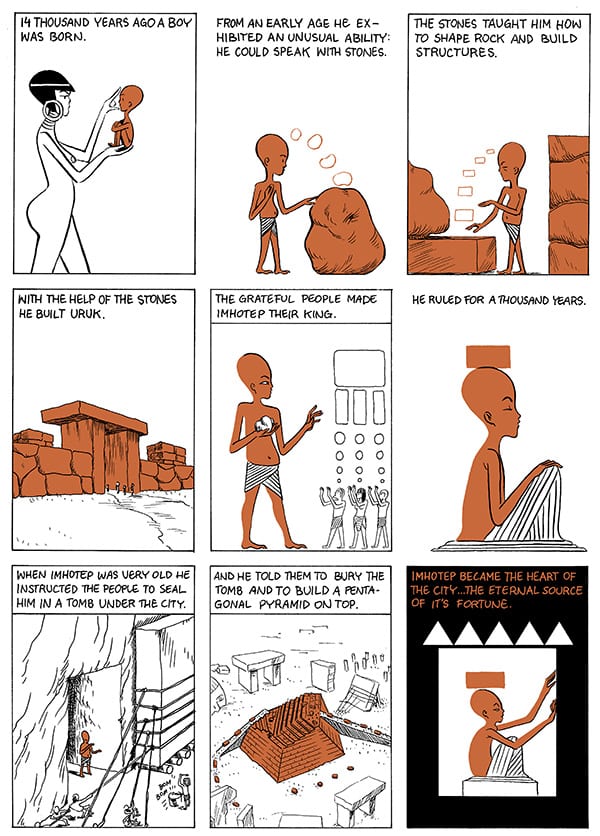

It’s one of the things that I really latched onto, for lack of a better term. The relationship between fact and fiction, and the relationship between what we accept as real and how that came to be. How our ideas about how the world were invented by people from scratch as “This is how things should be!” Over time it becomes naturalized as “This is how things have always been!” This is one reason I’m interested in history, ancient history, and fake ancient history. Because a lot of those things are bound up with each other. You can see a lot of texts and places where history could’ve taken a different turn, gone the wrong way or the right way, whatever you want to call that. These counter-factual histories, alternative histories are always interesting. That’s one of the things I always try to excavate in my work. Sometimes it’s really small, like “what if we never had cellphones?” or “what if all cellphones are really different cellphones?” Who decides that this is the right formfactor? Sometimes it’s really big: whole civilizations and whole philosophies. I don’t know if that really answers anything.

That answers the question. I didn’t even ask a question! Going back to Ignatius Donnelly, I had heard of him before but didn't know much about him, and when I was reading Trans Atlantis I couldn’t tell if you were making stuff up or not. [Kaczynski laughs.] I couldn’t tell if it was on the level.

It’s mostly on the level. [Laughter.]

It sounds like you’re done with Trans Terra now. It’s put to bed?

Almost. I’m still putting some final touches on that. I should’ve been done with it, probably a month ago. But I was late with the Fantagraphics book. It's late, but I’m almost done with it. Very close. And next, I’m working on a short piece for Twin Cities Noir, which is an anthology of detective noir fiction, put out by Akashic books.

I imagine it's mostly prose, right?

Yeah, it’s mostly prose. I was invited to be the lonely cartoonist in the pack. I’m doing a story about the Skyways. The Minneapolis Skyways. And then later after that, I really don’t have any major plans, besides running Uncivilized Books. I’m trying to figure out what the next project is going to be. I have a few choices. I would like to do a book about Ignatius Donnelly. I don’t know if I’m ready to start it yet, but that might be the next project. And then some other fiction stories I’d like to do. But they’re still simmering. I don’t know what’s next. We’ll have to see once I’m done with this detective fiction that I’m doing for Twin Cities Noir.

I haven’t read any exactly straight crime from you. Have you done that before?

Not really. And this isn’t really that straight a crime story that I’m doing for them. It’s a genre that I’ve actually disliked in the past. I really like Sherlock Holmes, but I’ve never really gotten into the classic noir authors. My girlfriend’s really into that stuff, but I’ve never really gotten into it. But lately I’ve found myself slowly getting sucked into it, and finding somethings in there that I like. I do like genre fiction in general. I like science fiction a lot, but crime has always eluded me.

What is it about it that you don’t like?

Everybody has their own ideas why they don’t like a specific genre, and usually it's the formula they don't like. Very specific things need to happen in each genre. I’m always drawn to slightly weirder stuff. I really liked the Paul Auster New York Trilogy, which has the trappings of the crime genre, but takes it into different places. Also the tough-guy talk, that just gets a little grating to me sometimes. I always want some kind of weird fake detective, not a tough guy. I’ll have to see where that goes. I'm sure I simply haven't read enough to find my niche in the genre...

Was Sherlock Holmes popular in Poland? Did you read it when you were a kid?

Yeah, he’s huge in Europe in general. It was very popular. I’ve only really read a couple of stories of Sherlock Holmes in English. The rest I read in Polish. [Laughs.] I pretty much know all of the stories really well. I remember watching the BBC serial in the ’80s and ’90s with Jeremy Brett. I really liked those. He’s just such a great character. He’s just such a weird — there’s something strange in them. I probably should read them in English, because I haven’t done that. But there’s something about them. There’s this weird undercurrent of strangeness, and I guess that part of it is just Conan Doyle himself. He's a strange character. He was convinced that fairies were real, right? On the one hand it's materialist and scientific, and at the same time there’s this undercurrent of strangeness underneath all that. I don’t know if I can describe it.

Yeah, it’s this kind of weird mix of super-rationalism and almost mystical super-irrationalism at the same time. But you should read it. I’d be curious to see what you would think, if it would be any better or worse in English. Sometimes writers read better in translation. There are people who say that Edgar Allan Poe is better in French, and that’s why he was recognized in France earlier than here. I don’t know if that’s true or not.

That’s interesting though.

Your style has changed a lot over the years, too. At the end of the book it's a little looser and more confident looking. Was that the result of a conscious decision, or just a natural evolution?

It’s both. When I first got the opportunity to do stories for Mome I thought, “I need to really tighten up and really be precise with the art.” I think some of those earlier stories I got way too tight and I felt like the life of the drawing was smothered. I do a lot of sketchbook drawing and I always like my sketchbook drawings better than I like the stuff that ends up on comics pages. As I was going along, I wanted to bring the sketchbook stuff into the stories; try to be a little more confident about it. I'm still not sure that I got to where I want to get to, but I definitely think that I’m more confident now, in terms of what I want to do.

At SPX, you were selling a little book of drawings, Structures, which basically seemed to be drawings of imaginary buildings, more or less. I know you studied architecture in school — was that book your way of getting out your old architectural impulses?

Yeah, a little bit. Originally I started those Structures drawings in preparation for the new story in the book. The main character was going to be an architect. But originally he was going to be a different kind of character; he was going to be this almost autistic character that created this weird architecture. With these drawings I was trying to get into the head of this weird autistic architect. He could, without any premeditation, create these structures directly in ink on paper. But as I kept working on the story, the character became less and less important, and then was written out of the book altogether.

I studied architecture and I feel like I learned more about drawing from architecture than I did from my art classes. I also have a degree in art: art and architecture. Architecture’s something that I never had a huge interest in before I studied it. I went into it mostly because I was like, “It’s a pragmatic major for someone who is interested in graphics and drawing.” I really fell in love with it as I studied it. Not enough to become an architect, but I love the way they think — about buildings, about space. I approached a lot of my stories in an architectural way, where I’m thinking and excavating certain layers and meanings out of specific places. I try to keep up with what's going on in the discipline.

You say that you learned more about drawing from architecture classes than art classes. What do you mean by that?

It’s possible that I had better teachers in architecture than I did in my art classes [laughs]. It felt like what drawing classes maybe used to be. Much more disciplined, very specific about techniques, about how to look at the world, and how to present certain things. My art education tended to align with the typical lament of the ‘90s cartoonists in art school. "Art School Confidential" type stuff. Where you’re just kind of let go and you’re feeling your way through it without too much instruction. In architecture I got specific instruction in specific techniques. At the time, I kind of resented that sometimes. But looking back, I’m really happy that I learned perspective [Laughs.] and other basic things that nobody was teaching me in art school.

So your sketchbooks. They printed a couple pages from your sketchbooks in Mome, and I’ve seen the stuff that you put online. One thing that struck me is that you, and I don’t know if this is true of your actual sketchbooks or just what you've published, but you sketch a lot of people, and a lot of faces — almost exclusively so, from what I’ve seen.

It’s fascinating, because in the interview that Gary Groth did with you for Mome, you talked a bit about how in your stories, you usually don’t put much of an emphasis on character, and were focused more on ideas. I think that might be changing a little bit, but that was the case at the time. And it was interesting to me that at the same time part of you, artistically, was very interested in people.

And that’s something that I don’t like about my art, to a certain extent. One thing that I have a difficulty with is creating identifiable characters who are distinct from each other. I tend to fall back sometimes on faces that I know how to draw well, that I’ve drawn many times over and over. Many of the characters in the Mome collection are very similar to each other in the way they look. That’s something that I’m starting to get away from in the latest story. That’s one reason I’m doing a lot of drawings of different faces, to get more comfortable with different facial types and different kinds of people, to be able to comfortably draw old people and the like. It’s something that I don’t do very much, but I’d like to do more. It’s something that's missing in my work. [Laughs.]

Yes, you need more stories about old people. [Laughs.]

If I’m more comfortable drawing something, then I’m also more comfortable writing it. The two are related. But you’re right, I do sometimes pick stories that — the very first story in Mome is all about cars. Before that I did not know how to draw cars properly. I made myself do that story so I would draw more environments, draw more of the things that I was avoiding at that time, cars being one of them. So I should just make myself draw the kind of people that I don’t ever draw.

I think your next story has to be set in a nursing home. You do a lot of stuff with institutions; I think it could work well for you.

Yeah, I could see that. I’m writing that down right now.

All right. [Laughter.] You can have that for free.