For the past few years, I’ve been working on a long comic about Virginia Woolf. As I read her diary and her letters, I’ve become increasingly convinced that she can serve as a guiding light for artists, and maybe particularly for cartoonists, on how to construct a fulfilling creative life. This is not because she lived some perfect version of the artist’s life, or because her viewpoints on art or on life are unassailable – indeed, her opinions on race and class are always uncomfortable and often inexcusable. However, she wrote so thoughtfully and over such a long period about her daily rituals and her creative struggles that they can serve as a mirror, a specific and clear example of how to construct your days that you might either follow or ignore.

In early 2020, I published a collection of quotes from Woolf’s diary with some commentary on why I found those quotes helpful. TCJ was kind enough to let me run a condensed and reworked version of that project here. The original version is more of a reference document, that you might return to in search of guidance on a specific topic. I hope this new version reads as a more coherent articulation on what I see as Virginia’s approach to creativity, why it was helpful to me, and why it might be helpful to you. All of the quotes that follow are from Virginia’s diary or her letters.

What Virginia Woolf Can Teach Us About Scheduling

Very early in her creative life, Virginia became a self-publisher. With her husband, Leonard – I’ll refer to them both by first name going forward, for clarity – she co-founded the Hogarth Press. Print runs for their early publications were in the low hundreds, and even the more successful Mrs Dalloway, published when Virginia was 43, had a first printing of 2000 copies.

July 1918 – I can’t fill up the lost days, thought it is safe to attribute much space in them to printing. The title page was finally done on Sunday. Now I’m in the fury of folding and stapling, so as to have all ready for glueing and sending out tomorrow and Thursday. By rights these processes should be dull; but it’s always possible to devise some little skill or economy, and the pleasure of profiting by them keeps one content.

This diary entry is the first of many times that Virginia describes the time she spent working on the Hogarth Press as useful to her writing. Both the physicality of the work, which let her mind wander, and the fact that it led to the production of tangible objects, seem to have been important. While the specifics varied, Virginia generally did not spend more than a few hours per day on her personal work. At times, this was due to the obligations of paying work, but she also filled her time with long walks, reading, a vibrant social life, regular vacations, and of course the Hogarth Press. She seemed to feel that an increase in the number of hours she spent on her novels would not necessarily lead to an increase in productivity – indeed, at times she indicated that after those few hours the quality of her writing began to decrease.

Scheduled tasks, such as the hours of folding and stapling that she describes in another diary entry as “my printing afternoons,” served in part as a safeguard against spending too much time on writing fiction, even in the periods of intense work on a project when that might have been tempting. But, like most of us, Virginia tried to plan out her months as well as her days.

August 1922 – I am beginning Greek again, and must really make out some plan: today 28th: Mrs. Dalloway finished on Sat. 2nd Sept: Sunday 3rd to Friday 8th start Chaucer: Chaucer – that chapter, I mean, should be finished by Sept. 22nd. And then? Shall I write the next chapter of Mrs. D. – if she is to have a next chapter; and shall it be the Prime Minister? [At this time, Virginia envisioned what would become Mrs. Dalloway as a set of stories about different attendees at a party] Which will last till the week after we get back – say Oct. 12th. Then I must be ready to start my Greek chapter. So I have from today, 28th to 12th – which is just over 6 weeks – but I must allow for some interruptions.

This is one representative example of a genre that appears throughout her diary: Virginia made careful plans about how she would spend her time, and set herself deadlines, which she almost never met. Virginia scheduled and rescheduled her time, mapping out the future – calculating how much time a project would take, when she would complete a draft, when she might publish a book or essay – even though she consistently underestimated how long her work would take.

There are a few lessons to be drawn from this. Even if she never got the timelines exactly right, the fact that Virginia continued to plan out her time in this way indicates that she must have found it useful. Maybe this was because a general sense that her draft might be done in, say, two months, and that she could then turn to another project, was useful even if the dates were slightly off. Maybe she found a balance between pursuing these self-imposed deadlines and letting herself off the hook when she couldn’t reach them. Maybe it was a way to motivate her subconscious; if she knew on some level that she would begin the next chapter of Mrs. Dalloway in a few weeks, might she begin to ruminate on what that chapter would be, before she began to actively work on it? But at times, this schedule fell to pieces. “A very good rhythm; but I can only manage it for a few days it seems,” she wrote about one period of productivity. “Next week all broken.”

Still, at any pace, Virginia believed consistently in the power of consistent work. “The only way to keep afloat,” she wrote, “is by working.” Again, for her, this rarely meant working sixteen hour days or rushing to meet an arbitrary deadline. Work accumulates. Working consistently may not mean working every day. Periods of low energy or poor mental health are natural and it may not be the right choice to ignore those feelings in a push towards a daily word count or weekly page count.

What Virginia Woolf Can, or Can’t, Teach Us About Money

We can’t discuss Virginia’s waxing and waning productivity, the fact that she spent weeks in bed with physical or mental ailments but also wrote a number of successful novels, without discussing her financial situation.

Like most self-publishers, Virginia was unable to support herself with her creative work for many years. This points to a central contradiction in her artistic life: on the one hand, she managed to balance writing fiction with work that paid the bills, like literary criticism, for decades before her novels became financially successful. On the other hand, Virginia rarely acknowledged and certainly did not seem to recognize the privilege conferred on her by the inherited income which helped support her and Leonard in their leaner early years.

Luckily, the Woolfs recorded a number of detailed financial figures at various points in their lives. I’ve roughly converted these amounts to current US dollars, because I’m trying to think carefully about how the Woolfs’ financial situation does or does not offer any lessons on how to live a sustainable creative life today.

Virginia and Leonard were never in a truly dire financial situation, but they also did not have excess funds to spend on most personal luxuries or on a vanity publishing project in their early years. Leonard’s careful accounting of their income in this period is a useful resource:

| Journalism | Books | Total | |

| 1919 | $7,834 | $0 | $7,834 |

| 1920 | $10,372 | $5,782 | $16,154 |

| 1921 | $2,808 | $597 | $3,405 |

| 1922 | $4,785 | $2288 | $7,073 |

| 1923 | $11,660 | $2,951 | $14,611 |

| 1924 | $9,497 | $2,744 | $12,241 |

Leonard provided these details, which he describes as “miserable figures” but not “particularly unusual [for writers],” to give a clearer picture of the life that he and Virginia led in these early years. So we must ask questions like: Where could you live off $7,000 or even $14,000 in 2020? In many large cities, this would be difficult if not impossible. What circumstances might lead you to feel comfortable launching a publishing house on this income? What does it say that Leonard neglects to discuss or even mention the couple’s inherited wealth in his tabulation?

On this last question, Quentin Bell’s biography of Virginia offers some details: “Virginia, who had inherited some money from [her late brother] Thoby and some from her aunt Caroline Emelia Stephen, had – “theoretically” as Leonard puts it – an invested capital of some 9000 GBP [$500,000]; and this yielded less than 400 GBP [$32,000] a year.” So the Woolfs were living on $39,000 a year in 1919; still a challenge, perhaps, but far less dire than Leonard’s figures make it seem. It’s easier to take creative risks when you’re guaranteed $32,000 each year!

Another figure that must be mentioned in discussions of Virginia’s finances is 500 GBP, or about $40,000 today. She argues, A Room of One’s Own, that a writer must receive this amount each year in order to produce creative work. Some critical writing on Room argue that Virginia chose this figure because it was her own yearly income from her inheritance at the time. I haven’t come across a primary source citing this amount, but maybe I didn’t do enough research, and it’s close enough to Quentin Bell’s 400 GBP mentioned above. Room is also rightfully criticized for assuming that, even if more women should be writers, those writers should all be of a social class where luxuries like inherited wealth and servants, if not at hand, certainly within reach.

Does this financial cushion, which Virginia had and which most of us do not, invalidate any lessons we might draw from her artistic life? Perhaps. At the very least, it’s a reminder that we should not always compare our own choices to those of someone in a very different set of circumstances. Even Virginia’s most cogent and direct advice is only a suggestion. Maybe it will be helpful, but maybe it won’t. Maybe it simply doesn’t apply to our own situation.

What Virginia Woolf Can Teach Us About Creativity

“Beauty,” Virginia wrote in a letter, “is only got by the failure to get it...to aim at beauty deliberately, with this apparently insensate struggle, would result, I think, in little daisies and forget-me-nots - simpering sweetnesses.”

This was even the case in terms of specific creative decisions. “I meant nothing by the lighthouse,” Virginia said, in response to another letter asking about the symbolic significance of that central image in To The Lighthouse. She knew where she was going, in other words, and considered her sentences carefully, but that doesn’t mean that she was considering the deeper, symbolic meaning of each word or each image. Even when she planned to deploy symbols consciously, she sometimes found herself going down a different path. You could argue that this was in part enabled by her careful focus on her craft – the writing and rewriting of an important sentence, until it felt just right, being more important than what that sentence might mean. Meaning, indeed, is never explicit but “only suggest[ed].”

Yet another letter communicates this same idea:

Sep 1930 – [I shall] let myself down, like a diver, very cautiously into the last sentence I wrote yesterday. Then perhaps after 20 minutes, or it may be more, I shall see a light in the depths of the sea, and stealthily approach - for one’s sentences are only an approximation, a net one flings over some sea pearly which may vanish; and if one brings it up it won’t be anything like what it was when I saw it, under the sea.

But this delicate balance – finding beauty without seeking it, creating meaning while only suggesting it, could be exhausting.

May 1920 – It is worth mentioning, for future reference, that the creative power which bubbles so pleasantly on beginning a new book quiets down after a time, and one goes on more steadily. Doubts creep in. Then one becomes resigned. Determination not to give in, and the sense of an impending shape keep one at it more than anything. I’m a little anxious. How am I to bring off this conception? Directly one gets to work one is like a person walking, who has seen the country stretching out before. I want to write nothing in this book that I don’t enjoy writing. Yet writing is always difficult.

First, let’s address the idea that working on art is like walking along a path you’ve seen before. This suggests you might know the general contours of the landscape, but perhaps not every nook and cranny. You know that your destination exists, because you’ve been there before, but you start to worry because you’re not seeing a landmark that you’re sure you remember from last time. You might prefer a slightly different metaphor: you’re walking down a new path with a map you’ve used before. You know the map is reliable, if you’re reading it correctly, so it will get you where you need to go. But the scenery is not familiar – so you start to wonder if your map might be wrong. You wonder if you should have chosen a different map, or an easier route. Both framings suggest that creation brings with it some fear and uncertainty. But they suggest that the walk itself, the act of putting pencil to paper, can be a comfort if you let yourself forget for a few moments about the destination and just enjoy your surroundings – if you’re the sort of person who likes to go on walks.

There is also obvious comfort here in seeing Virginia struggle through the challenges and even the boredom of creating work that we now see as successful. But let’s focus on one line that is more subtly interesting: “The sense of an impending shape keeps one at it more than anything.” This suggests that a vague idea of a book’s goals can be a motivator and a guiding light. Note that Virginia doesn’t say “a specific plot” or “an exact knowledge of what the book means.” But there’s a clarity, even an excitement, of feeling your work congeal into some form, even if that form is uncertain. So while deciding exactly what you want a book to convey before you begin it is probably unwise, complete ignorance of what you are working towards is also unhelpful. September 1920 – I began to wonder what it is that I am doing: to suspect, as is usual in such cases, that I have not thought my plan out plainly enough — so to dwindle, niggle, hesitate — which means that one’s lost. Like all of us, Virginia could be fickle and self-critical when talking about her own approach. Just a few months after “the sense of an impending shape” was enough to keep her going, she longs for a clearer plan of action. So it’s a difficult balance: thinking through the goals of a work, but not thinking through them too much.

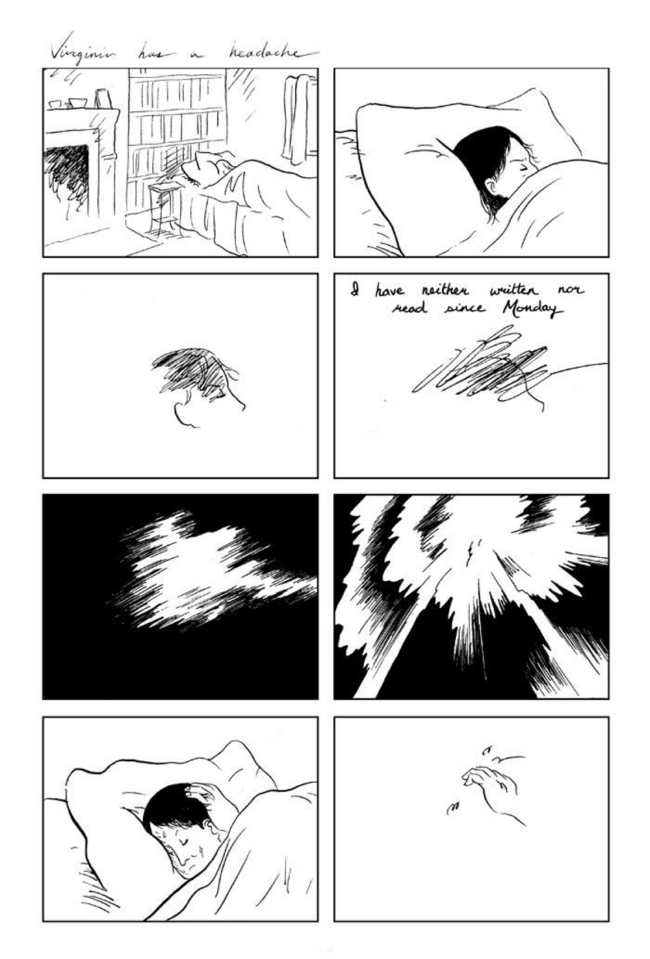

What Virginia Woolf Can Teach Us About Pain and Not Writing

I disagree firmly and without reservation with claims that Virginia’s mental health struggles made her a great writer. Biographers including Virginia’s own nephew, Quentin Bell, have claimed that Virginia’s weeks in bed, often with severe headaches and at her lowest mental points, were an important part of her creative process. But other circumstances, such as her long walks, were just as useful to her as opportunities for quiet contemplation. Plus, of course, she almost always couldn’t do any writing while bedridden. In other words, neither Virginia’s death nor the mental illness that led to it should be romanticized in any way. That illness was not essential to her creative process. It does not invalidate her thoughts about the value and beauty of life. This has been written about at length in many places so I won’t rehash those arguments here. Of course, Virginia’s mental health was an important part of her life, and it can be helpful to read about how she works through those issues.

September 1930 – I shall attack The Waves on Thursday. So this illness has meant two weeks break – but as I often think, season of silence, and brooding, and making up much more than one can use, are fertilising. I was raking my brain too hard.

Virginia sometimes fell into periods of excess in terms of her writing, working furiously and for longer each day than was typical. Sometimes she felt this was necessary – for instance towards the end of a novel, as she worked to bring together its complex strands – but other times she seems to have recognized this as a misstep: “I was raking my brain too hard.” This sometimes led, as in the quotes above, to periods when she was confined to her bed. So as much as we might imagine Virginia as someone who diligently made time for hobbies and friends, who worked on her writing for only a few hours each day, she did stumble. As we all do.

October 1934 – I am so sleepy. Is this age? I can’t shake it off. And so gloomy. That’s the end of the book. I looked up past diaries – a reason for keeping them – and found the same miseries after Waves. After Lighthouse I was, I remember, nearer suicide, seriously, than since 1913. It is after all natural. I’ve been galloping now for three months – so excited I made a plunge at my paper – well, cut that all off – after the first divine relief, of course some terrible blankness must spread. There’s nothing left of the people, of the ideas, of the strain, of the whole life in short that has been racing round my brain: not only the brain; it has seized hold of my leisure: think how I used to sit still on the same railway lines: running on my book. Well, so there’s nothing to be done the next two or three or even four weeks but dandle oneself; refuse to face it; refuse to think about it.

You reach that exciting, singular, exhausting moment of finishing a project. You’re relieved, but you also feel that something has been lost. Hopefully, this doesn’t push you towards suicidal feelings. If it does, please seek help! But some amount of sadness is natural. This isn’t even self-doubt about the quality of a work, which Virginia also felt, but a sense of loss because you can no longer turn over in your mind ideas that you’ve been thinking about for months or even years. Personally, I’m drawn to the practical advice at the end of the quote. Put the work aside for several weeks (or, of course, for a different amount of time that makes sense for you). Don’t think about it. Recognize the feelings of loss as unavoidable but transitory.

What Virginia Woolf Can Teach Us About Time and Getting Older

January 1920 – The day after my birthday in fact I’m 38, well, I’ve no doubt I’m a great deal happier than I was at 28; and happier today than I was yesterday.

Virginia’s first novel, The Voyage Out, was published when she was 33. Mrs. Dalloway, arguably her first real masterpiece, was published when she was 42, and she produced most of her best work in her forties. In a time when we’re expected to find creative success quickly, and when it’s easy to compare ourselves with those who have been successful at a young age, I find Virginia’s path incredibly comforting. As she indicates here, she was not only more creatively successful but happier in her thirties and beyond. She commented on this many times, also writing, “At forty I am beginning to learn the mechanism of my own brain – how to get the greatest amount of pleasure and work out of it. The secret is I think always so to contrive that work is pleasant.”

However, discussions of her publishing history ignore the meditation of that simple statement: “I’m happier today than I was yesterday.” This is not because Virginia’s happiness was a constant, upwards trajectory – certainly not, as it isn’t for any of us – but because she woke up on that particular day, and felt happy, and in the moment that was enough.

July 1925 – But I don’t think of the future, or the past, I feast on the moment. This is the secret to happiness, but only reached now in middle age.

Virginia’s creative success in her forties and beyond was in no small part, she seems to tell us, because she had spent more time inside her own head. She understood how to convert her thoughts into words. She understood what made her writing strong and how she could make it stronger. She understood how to make her work pleasurable. It seems to me that there are no shortcuts to reaching this stage – there weren’t any for Virginia. In other words, her route to creative success was both as simple and as complex as it could possibly be: she just let the work, and time, accumulate.