A Snapshot of Our Profession

Last weekend I attended something called the Left Forum, at Pace University in New York. I’d been invited to be on a panel of editorial cartoonists by Ted Rall, who’s never done anything but professional favors for me, so I said yes. This turned out to be something like one of those fabulous book deals where a publisher will print up a handsome embossed gilt-edged edition of your book for only $75.00. It emerged that invited speakers were required to pay admission to the event--which amounted, for one two-hour period, to $15.00. (Ted, to his credit, graciously offered to cover the cost for me, but I crankily declined.) To me this seemed like further confirmation of the Left’s penny-ante amateurishness and well-earned inevitable doom. Having agreed to go, I was reluctant to renege, but in token passive-aggressive protest I put together a slide show of all my anti-Leftist cartoons and took half a 10mg Percocet I happened to have for totally legitimate medical reasons. I also took along my own bottle of water because I knew no way would they have bottled water for us there.

I was not wrong. Needless to say the whole thing was marginal and loserish and sad. The crowd seemed to consist largely of grizzled, embittered Marxists, and the tenor of questions spanned the range from aggrieved to despairing. Why isn’t the Left availing itself of the power of political cartoons in this post-literate culture? Union newspapers used to have cartoons in them every week. Why is there no market for editorial cartoons anymore? You literally can’t give them away to magazines like Mother Jones or The Nation. Why are mainstream newspaper editorial cartoons so bland and craven and bad? Why can’t we seem to communicate our message effectively? One of the panels I saw on the schedule was titled: “What Is To Be Done?” It would’ve made a good theme for the weekend.

The afternoon wasn’t a total loss—no time spent on opiates is ever wasted, plus I did chat with a cute girl afterward. It also inspired some melancholy reflections on the present state of my old profession. It seems to me there are some parallels between The Left and the world of comics. For one thing, they both tend to put together poorly organized conventions. They both, as groups, suffer from chronic low self-esteem and a default attitude of defeatism. And one of their basic fallacies is an inability (or refusal) to distinguish between things that can be changed and things that can’t.

The afternoon wasn’t a total loss—no time spent on opiates is ever wasted, plus I did chat with a cute girl afterward. It also inspired some melancholy reflections on the present state of my old profession. It seems to me there are some parallels between The Left and the world of comics. For one thing, they both tend to put together poorly organized conventions. They both, as groups, suffer from chronic low self-esteem and a default attitude of defeatism. And one of their basic fallacies is an inability (or refusal) to distinguish between things that can be changed and things that can’t.

Admittedly, this can be a tricky distinction under the best of circumstances, which is why the Serenity Prayer exists. After all, who would have imagined, at the turn of the previous century, that institutional racial segregation or child labor would be eradicated in this country, or that comic books would one day win Pulitzers or be reviewed in the New York Times? So it seems not unreasonable to hope that one day we might have universal health care in America, or that, within our lifetimes, a mainstream article on graphic novels might not begin with the words: “ZAP! BIFF!! POW!!!! Comics aren’t just for kids anymore!” But currently the Left is trying to figure out how to rebuild an organized labor movement in a country that no longer makes anything, while my colleagues are still fretting over how to get their editorial cartoons into daily newspapers and monthly magazines even as print media goes the way of stained glass. Essentially, they’re both urgently asking: How can we make it be 1960?

With respect to my former colleagues, I couldn’t help but think: Newspapers? Why bother? They’ll all be gone soon. Sure mainstream editorial cartoons are shameless lazy hackwork but so’s Beetle Bailey--so what? Who under the age of sixty-five is still reading a daily paper, anyway? I read the New York Times online and so does everyone else I know. People younger than me get most of their news from websites or cable comedy shows. And stupid people watch Fox. Scheming to get cartoons into newspapers at this point is like trying to make sure your indie film is distributed through Blockbuster.

The night before this depressing gathering I’d attended a reading by the Pizza Island studio, also known (among me) as the Pretty Girl Cartoonist Club (P.G.G.C.). This event filled the big back room of a bar in Brooklyn, a space generally used for live music performances. I had to sit on a railing, and still people crowded in front of and behind me, and it got claustrophobic and hot and carbon dioxidey. I felt certain that fire codes were being violated. All these people had come out to see internet microstars like Kate Beaton, whose erudite and silly webcomic Hark! A Vagrant has an unheard-of 25,000 followers on Twitter. Afterwards, at the bar, I talked to Aaron Diaz, another web cartoonist, who’s made a living for the last few years from online donations and merchandise sales. On an unworthy personal level this made me feel sorry for myself and superannuated and old, as I never understood how to make any money from the internet until it was too late. But, on a less selfish level, it reminds me that cartooning is hardly moribund; it’s just thriving in different niches.

Web comics are not just cartoons in a different format; new forms determine new content. The first time I looked at web comics like xkcd or Natalie Dee I felt plodding and obsolescent, a cranky allosaur having circles run round him by scampering mammals. All my fussy cross-hatching and detail and my elaborately constructed gags seemed labored and unnecessary compared to these clever little figments. The drawing is the minimum necessary to convey the idea—clip art, stick figures, Photoshop oblongs with dots for eyes, the kinds of images that are intelligible from half a block away on a T-shirt. The gags are quick hits, lol-funny and disposable, most of them evaporating from your head the instant you click on the next one. (Even Beaton’s public reading style reflects this aesthetic—understated and offhand, almost dismissive, not trying to sell the jokes, hardly pausing for laughs: Here’s this one, here’s another, on to the next.) The whole point is just to get the idea down, tossing off one after the other, in hopes that one of them will get stuck in the collective head of the internet and go viral. They’re not unlike old science-fiction stories where the characters were all interchangeable and the plots nonexistent because the whole point was just to pose a single question no one had ever asked before: What if you could build a four-dimensional house? What if you went back in time and changed one little thing? What if there was a world where people had never seen the stars?  None of which I mean to sound patronizing; xkcd achieves moments of nerdy poetry with its stick figures, and although Kate Beaton’s drawing looks deceptively rushed and sketchy it’s as expressive and funny as Patrick McDonnell’s Mutts, and some of her punchlines resonate long after you’ve shut down your laptop. But their work is as different from the kind of cartooning I did for a decade as modern movie acting is from stage acting.

None of which I mean to sound patronizing; xkcd achieves moments of nerdy poetry with its stick figures, and although Kate Beaton’s drawing looks deceptively rushed and sketchy it’s as expressive and funny as Patrick McDonnell’s Mutts, and some of her punchlines resonate long after you’ve shut down your laptop. But their work is as different from the kind of cartooning I did for a decade as modern movie acting is from stage acting.

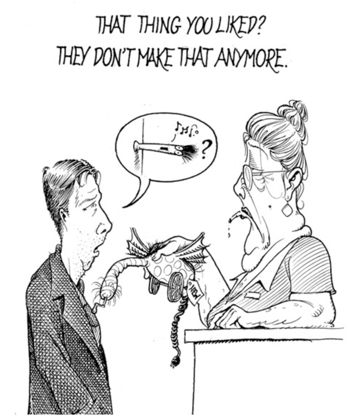

This is all easy for me to say with some sanguinity—I quit cartooning two years ago and became a writer instead. (As Ted Rall said: “Only to a cartoonist could freelance writing seem like a cash cow.”) If I were still trying to be a political cartoonist, doubtless I would still be as frustrated and bitter about the futility of it all as my colleagues are, and a good deal whinier. I’m not happy about any of this, any more than I’m pro-global warming or looking forward to the sun bloating up into a red giant. It still pisses me off that I was never paid more than twenty dollars a week for my work. It disgusts me that in the internet economy what’s called “content”—what we used to call “art”—is inherently worthless, and all revenue has to come from charity, advertising, or hawking crap like T-shirts and coffee mugs. It makes me furious on behalf of my friends when graphic novels they’ve worked hard on for years are scanned and uploaded in their entirety for free within a week of their publication.  And it breaks my heart to hear gifted and hardworking colleagues of mine who can’t make ends meet tell me that when they were kids, reading Peanuts paperbacks, all they wanted was to grow up and be cartoonists. They didn’t want to be Charles Schulz, with a merchandising empire and TV specials and their own skating rink--they just wanted to go to a desk, draw their four panels a day, and go home. It’s such a modest ambition, now utterly unrealizable. That job no longer exists; it vanished before they could get there. They were like kids writing fan letters to Jane Austen, or wishing on stars that burned out a thousand years ago.

And it breaks my heart to hear gifted and hardworking colleagues of mine who can’t make ends meet tell me that when they were kids, reading Peanuts paperbacks, all they wanted was to grow up and be cartoonists. They didn’t want to be Charles Schulz, with a merchandising empire and TV specials and their own skating rink--they just wanted to go to a desk, draw their four panels a day, and go home. It’s such a modest ambition, now utterly unrealizable. That job no longer exists; it vanished before they could get there. They were like kids writing fan letters to Jane Austen, or wishing on stars that burned out a thousand years ago.

Of course the percentage of aspirants who’ve ever actually made a living in the arts has always been very low. In some ways the situation is the same as ever: the people who control delivery systems make millions, the people who actually make things are lucky to make rent. (Now who’s the embittered Marxist?) But the internet appears to be an environment as hospitable to art as the surface of Venus is to life—Garry Trudeau recently called it a “revenue-free zone.” In a way, the teen anarchist in me rejoices at the irony of capitalism having finally devised an invention to render profit impossible, an economic Doomsday Machine. But the guy who just would’ve liked to make a living drawing cartoons is less gleeful. When you’re young, it’s exciting and fun just to have your work published in the local alternative weekly, or posted online, “liked” and commented on and linked to; but eventually you turn forty and realize you’ve given away a career’s worth of labor for nothing. What’s happening in comics now is what happened in the music industry in the last decade and what’ll happen to publishing in the next. Soon Don DeLillo will be peddling T-shirts too.

It remains to be seen how long anyone gets to be famous or successful in the saccadic attention span of the internet—what is a web cartoonist’s professional lifespan before the eyeballs all turn someplace else? The Onion recently reported: “Time Between Thing Being Amusing, Extremely Irritating Down To 4 Minutes”. This restless insatiate boredom that compels us to click on the next thing and the next thing and the next may mean that web cartoonists’ careers will be even more tenuous and ephemeral than those of the cartoonists they’ve displaced.

It remains to be seen how long anyone gets to be famous or successful in the saccadic attention span of the internet—what is a web cartoonist’s professional lifespan before the eyeballs all turn someplace else? The Onion recently reported: “Time Between Thing Being Amusing, Extremely Irritating Down To 4 Minutes”. This restless insatiate boredom that compels us to click on the next thing and the next thing and the next may mean that web cartoonists’ careers will be even more tenuous and ephemeral than those of the cartoonists they’ve displaced.

The afternoon before the Pizza Island reading I’d gone to a show of Norman Rockwell’s paintings at the Brooklyn Museum. Mid-twentieth century, Rockwell was the single most famous artist in America. Before him, magazine illustrator J.C. Leyendecker was what today we’d call a celebrity, a profligate man about town in the roaring twenties. Illustrators like Charles Dana Gibson, James Montgomery Flagg, and Bernie Fuchs not only earned good livings, acclaim and public renown with their work, but created iconic images that permeated the culture in a way that, in recent years, only Shepherd Fairey’s image of Obama has. Not to be a big bummer, but that show served, among other things, as a memento mori, a reminder that whole lucrative and prestigious professions and highly cultivated and enduring art forms can just plain vanish along with their host media, with the same pitiless logic as the extinction of species follows the eradication of their habitats. I don’t suppose anyone was very happy when their cozy caves with good lookouts or the little wood where you could pick deer off by the dozen or that lovely meadow where the foxglove grew ended up under a mile of ice, either. We live, once again, in changing times. The weather is getting funny. Our choice, I fear, is the same crappy deal as always: adapt or die.