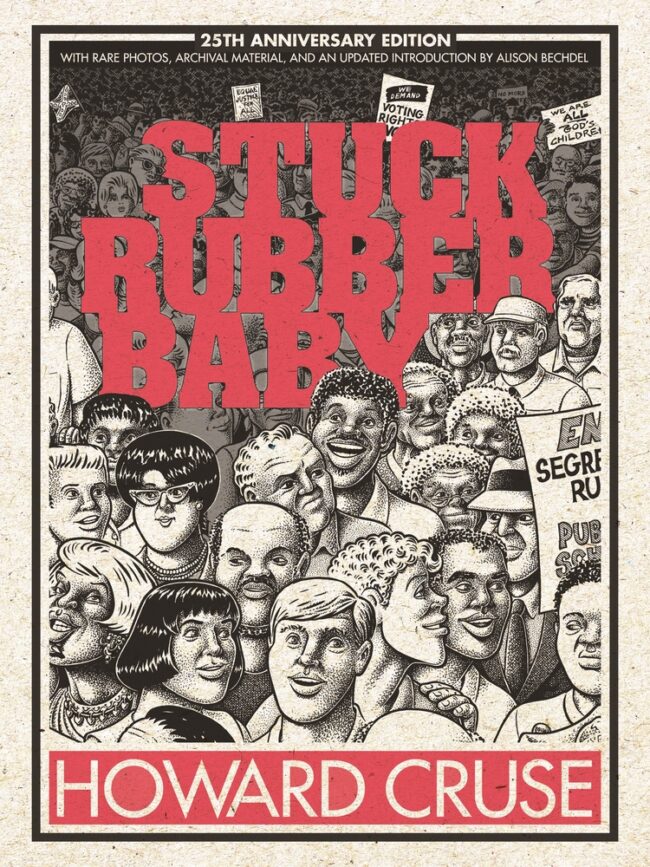

In September of 1995, DC Comics (through their Paradox Press imprint) published Howard Cruse’s Stuck Rubber Baby. It was rightfully praised as groundbreaking and heartfelt, a career highlight from one of the unsung heroes of underground comics. At that time I was an 18-year old journalism student at Pace University in New York City. I had been a fan since stumbling across a copy of Early Barefootz (Fantagraphics, 1990) at a convention a few years earlier, and with a few phone calls (in which I must have sounded reasonably professional), I talked my way into a sit down interview with the author.

Howard Cruse welcomed me into his home in Queens, and handled my clumsy questions with grace, humor and humility. We talked about his life, his career, and the lengthy creation of Stuck Rubber Baby. Excerpts from that chat ran in my college paper, as well as Indy magazine.

We kept in touch for the next 24 years. I took his cartooning class at the School of Visual Arts, and I taught him how to set up a website, which I also hosted for many years. Every now and then he would reach out with a question about some computer issue or another, or I’d receive a holiday card, or run into him at a convention. When I applied to graduate school, he wrote a recommendation letter. He was always there, always friendly, always warm and open.

Howard passed away in late 2019, and while he had been dealing with health issues, losing him was a real shock. He remains one of the kindest and most generous people I’ve ever known. Ask anyone who knew him in any capacity and you’ll hear the same.

Recently while spring cleaning, I stumbled across a couple of old microcassettes from that afternoon I spent with Howard in 1995. Presented here for the first time is the complete interview. While I was just a dopey 18-year old doing my best Gary Groth impersonation, Howard was gracious and thoughtful. Hearing his friendly southern drawl on this recording after all those years was quite an experience, and it is a real pleasure to share this complete conversation with you.

The 25th anniversary edition of Stuck Rubber Baby was released in 2020 by First Second Books. - Jason Bergman

* * *

Jason Bergman: Let me start by saying I loved Stuck Rubber Baby. How did you start the project?

Howard Cruse: Well, I was at a loose end because the Wendel series had ended in 1989 and I was casting about for what my next creative direction would be. It was a year of small projects. A friend of mine suggested that Paradox Press, which at that time was called Piranha Press, a division of DC Comics, was interested in offbeat things and I shouldn't assume that they would not be interested in me doing a graphic novel. I'd always assumed it would be impossible for me to do a graphic novel because of the time it would take, and how I would I ever live while doing it?

But DC, being a part of Warner or Time Warner, had lots of money to spend that the other publishers I've worked for didn't. It was a foregone conclusion that they couldn't come up with a big advance. I called up the editor and said, "Do you want to talk to an underground cartoonist? How's about possibly doing a graphic novel?" He had me come in, we chatted about it. It turned out he was very open, not only to a novel with a gay theme, but also to me working, more or less, as I had worked in underground comics, which is with a great deal of creative autonomy. I knew that I could not function creatively with the kind of supervision at every stage that mainstream comics get.

Basically, I needed for them to look at my past work, decide whether or not they thought I had reasonably good judgment, establish ground rules but basically let me do it on my own. I wanted to do a book that would be a real novel, not just a puffed-up comic book story. I was looking for things in my life that I felt strongly enough, cared enough about to carry that many pages so I wouldn't get bored a part of the way through, and wish I wasn't doing it.

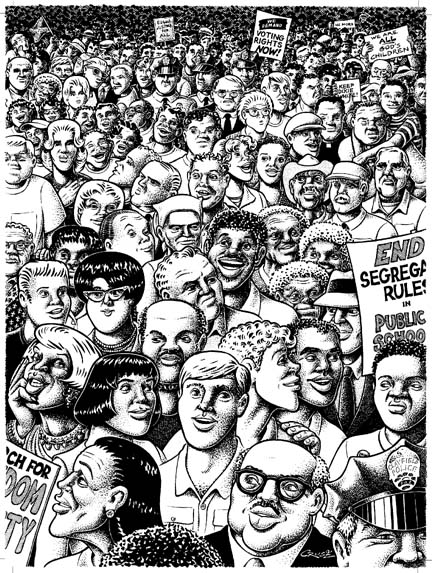

A couple of things in my life that I'd never had a good chance to deal with in my cartoons were the impact of the civil rights movement, the impact that it had had on me when I was coming of age and going to college in Birmingham when all of the demonstrations were going on. That, plus the experience I had had as a gay man trying to be straight who had inadvertently fathered a child. Those two things seemed like fertile ground for something that would have a long arc, a long narrative arc.

Plus the chance to depict the gay subculture down south all those years before Stonewall, because most of the fictional literature that I see, and I really don't see a lot, unfortunately, I don't have time to read it and don't have money to buy it, but I don't hear much about fictionalized depictions of pre-Stonewall gay South. I thought that would be something I could add to the literature that would give young folks a picture of how it used to be.

I thought with all those things mixed together there was a good novel in it. Beyond that it was, as with any work of fiction, trying to find the characters that would tell a story that was interesting.

Now that it's been published, what kind of reaction inside the comics industry have you had?

Well, this book has been talked about within the industry for a while. [laughs]

For a while there, everywhere I turned it was there. There was a page printed in The Comics Journal six months ago.

Yes, it's actually longer than that, a year ago [issue #170, August 1994]. There was a page that was printed in a collection called Comic Book Rebels [Plume, 1993], that Steve Bissette put out, over a year ago. It's been a four-year project. A lot of people have known it's been in the works. I kept the title quiet until about a year ago. I was afraid people would get sick of hearing about it. In the way everyone was aware that Truman Capote was doing Answered Prayers for years and years and years and years, I didn't want it to be something that was that old hat by the time it came out.

As the book took shape and there was enough of it to show around, reaction was consistently favorable within the industry. It was a little unnerving, it was just a lot of people said, "I really like the way this is going." Excited about it. There was a build-up of excitement. So far, the early reviews have been almost all positive. Some of them had quibbles. Some have just been a writer's dream. I haven't had an experience before of doing something that had as many people in its corner. This does and that's very gratifying. Now, we're waiting to see if the buzz results in good sales.

You mentioned Steve Bissette before. I understand he wrote you a letter for the Guggenheim?

He did that. He's used part of that letter-- we were lobbying the National Endowment for the Arts to quit being so stuffy about comic books-- there's no way you can apply for a grant from NEA in the comic book field because of simply the way they describe submissions. If it's fiction, it has to be typewritten with margins. If it's images, they only allow you to send slides. They just rule out a whole genre in that way. We wrote them letters and said they should change that. Of course, since they're basically just trying to stay afloat they were not interested in comic books.

Did anything actually come from the Guggenheim?

No. I applied every year, year after year. I never got a thing out of them as I did with the New York Foundation for the Arts. I was really desperate for some assistance on this book because it took so much longer than I intended, even though it would have been a good deal if I had been able to do it in two years. The advance was woefully inadequate for four years. Like it says in the book, I had to struggle to get that extra money.

A lot of people lately have been saying they want to expand the readership of comics, but most comics are targeted toward a very limited audience. How's the reaction like outside the industry been?

Well, it's a little too soon. We have had the early reviews that have been very positive and I've been pleased that they've been positive outside the gay world as well. But we're still-- the book is only really just showing up in bookstores now. I can't tell much about reaction.

Another thing is, this is really a book without any stereotypes whatsoever. It's very nice to read.

I tried.

[laughs] For starters, it's a book that portrays the lives of gay men without ever mentioning the "A" word.

Yes, that's intentional.

Hollywood could learn from it.

[laughs]

Has there been buzz over optioning the book?

If there is, it hasn't reached me. I could use the option money. I have some doubts about how well this would translate into a movie simply because I very consciously used comic book syntax to tell the story. There's a lot of things in there that-- there are certain things movies can do that comics can't do. There are certain things comics can do that's hard for movies to do.

For example, the scene at Sammy's memorial, when he has his, whatever experience he had and it's unclear exactly what the experience subjectively-- what was objectively happening. It would take a very creative director to know what to do with that moment which is a climactic moment of insight for him, so you couldn't just leave it out. You'd have to find some sort of analogue in cinematic terms, and that would be tricky.

I think a lot of the book would do very well, it has real-life characters, you can imagine actors playing them. If you could lick some of the places where it goes into expressionism, and surrealism or something; maybe there's a movie in it. I would love for somebody to put up some option money. [laughter]

I understand you used a lot of references for the book. Did you have any models?

The physical people models?

Right.

Eddie [Sederbaum, Cruse's partner and eventual spouse] was frequently summoned to play the guitar, to look like he was being gay-bashed, to anything that required a little special awareness of anatomical positions that I couldn't pull out of my head easily in three dimensions. I would get Eddie to do or other friends of mine, who happened to be around at the time, that I could grab them. I have all these, that scene when Toland is talking and his lover is standing behind him with his hands on his shoulders. I grabbed some neighbors, "Stand this way now," lots of pictures at different angles. That's about the models. I certainly didn't hire any.

I wanted there to be a sense of reality, and so I did try as much as I could with limited resources to do everything I could to base myself visually and historically in a context. This book of oral histories of the civil rights movement called My Soul is Rested, by Howell Raines-- he's the editorial page editor at The [New York] Times now. He and I went to college together. As a book I think he did a beautiful job of getting people's stories on paper.

There were a few books like that I read, although ultimately I felt like I was in danger of reading too many of those, and I needed to step back and just remember, use my own memories a lot. Also the memories of others, I got people together in Birmingham: people who had been part of the civil rights movement, people who had been part of the gay subculture, and just have them tell me stories, some of which were used, very close to the actual stories in the book.

I took snapshots of old cars. Some of this you know from the acknowledgments, you know all over Brooklyn that Scott[1] had collected old cars, and I do not know how I could have done the book without that because it's very difficult to find photo reference of the interiors of cars. You find lots of pictures for the exteriors, but what the dashboard looks like, and what the seat covers look like, things like that, it's very hard to find. The Sears and Roebuck catalog was vital for clothing because the picture reference collection in the Birmingham-- the New York Library Picture Collection, for clothing, almost all comes from fashion magazines, so it's all high fashion and I wanted to know what everyday people wore. Somebody said, "Go to the Fashion Institute of Technology" and they kept old Sears catalogs.

That now, not only was great for the clothing, but for coffee pots and lots of little implements in the story. I found in my mother's basement a lot of old newspapers from that era, because she's a packrat and collects lots of old publications. I even found some old Ku Klux Klan literature and some old racist newspapers for that era.

I gathered things here and there, those things that I gathered that I have here in the house plus stuff that I would borrow from the picture collection at the library, that's the kind of reference I-- I would never claim, by the way, the book is flawless in its depiction, because a real historian would know how to get things more precisely than I did, but what I was trying to do was avoid glaring errors, the kind of things that take you out of the story. A VCR in 1960, [chuckles] I didn't want that kind of thing to happen, right?

In Stuck Rubber Baby, you managed to maintain a large sense of optimism. But then in your stories in Gay Comix, you project yourself as being very cynical towards the future. Are you hopelessly lost somewhere in between?

What I usually say is that I'm pessimistic in many ways about the future, but I believe that the only useful way to spend your life is behaving as if it's possible to counter negative trends and improve things, and I try to do that in my work and it just has to do with one's own self-respect. Also, however, the civil rights movement, as it played out in Birmingham, demonstrated that street activism works.

Birmingham has changed fundamentally because of what happened in the '60s, and it was considered absolutely rock-hard segregationist country when it started. Martin Luther King, I think once said, "If you could integrate Birmingham, you could integrate anywhere." I do know that it is possible to change the course of events, whether humankind as a whole is going to get its shit together, I have my doubts. But I do feel that, incrementally, in different places, one can make a difference if you really try.

I think that sense of optimism in the book, it really has to do with my rejection of the notion that the only proper stance in the world is cynicism. I really feel that cynicism is an extremely destructive attitude, and distinguished from skepticism, which I think is important for having some reality check on things. I knew people, I know people today, I knew people back then who-- the motives they presented in doing what they did were noble motives, they did not have hidden agendas, they were not perfect people just as the people in Stuck Rubber Baby are not perfect people, but they were trying, they were genuinely admirable people. The notion that somehow because all problems were not solved in the '60s therefore we should turn up our noses at people who put their lives on the line, I think is just a horrible idea.

I think, in the ending of the book, as Toland reflects back on people like Reverend Pepper, and Adeline Pepper, they keep him from ever surrendering to cynicism because they were genuinely worthwhile and noble people, and people like that inspire other generations to have higher motives.

I understand your father was a preacher? What was it like growing up in that kind of family? Was the strip "Jerry Mack" a way of reflecting that?

My father was not quite as tied up in knots as Jerry Mack; for one thing, he wasn't a closet gay. I knew a preacher, on whom the story "Jerry Mack" was based, and I've known many people like that, that level of religiosity really frightens me how much people can get caught up in it. But the life of a preacher's kid, it just has certain special qualities and I’m just a little touched-- in the book when I just mentioned how Les could be partying at the gay bar one moment, and then when summoned he assumes his role as the preacher's son and is very helpful and at his father’s beck and call. There's a sense in which you're always-- may be called at any point to play the role of the really good son, if you're a male. I certainly was more The Best Little Boy in the World.

I responded to that book a lot, certainly the pressure, not only because I felt I was flawed inside and so I had to overcompensate by being just a wonderful little boy. Added to that was the expectation that you'd be especially wonderful if you were a preacher's kid, so that does things to your head and those people who were preacher's kids, one way or another, they've got to deal with that in their later life.

My father was an admirable man. He and I disagreed more and more the more I began to think for myself about all sorts of things. But he genuinely believed in living his life according to his beliefs. He was not a hypocrite, and he took risks for his beliefs. He didn't always take the safe way. He was willing to ruffle some feathers to try and bring his vision of Christianity to other people, and so I think I'm like him.

I do believe that once you honestly, in your heart, have a sense of a correct course of action, that you should do it, regardless of consequences. I'm not saying I always live up to that ideal, but that is a goal that I like to have in my life.

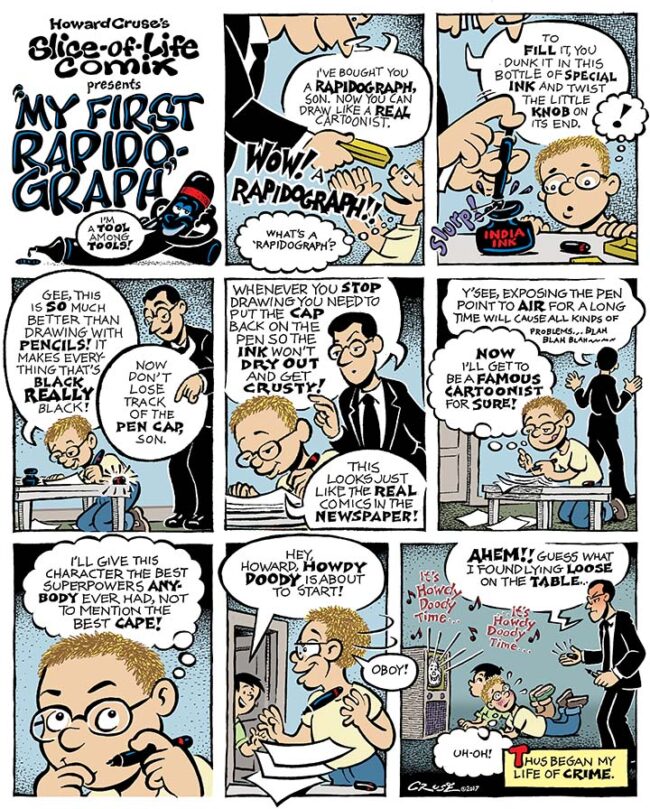

Did you always want to be an artist?

Yes. I discovered I enjoyed drawing when I was five or six or something, and then, sometime when I was around eight, my parents told me that people actually earn their living doing that. That sounded great, so I set my ambitions on being a cartoonist from that time on. Except that I had a diversion when I was in college, into theater, because the theater director at Birmingham-Southern College where I went was a very charismatic man with ideas about what art is that influenced me greatly. He became a role model, and for a while I thought I would be [an] academic theater director like him.

I wrote a lot of plays and directed them, and I still would like to get back into theater at some point. Not necessarily professional theater, but I enjoy that form of art and like to express myself that way. Once I was out of school, and I found myself in New York, after having dropped out of Penn State University, I basically realized that it's a lot less complicated to pursue an art form where you can just do the art form yourself rather than having to have an organization and a building and stuff to do it. Theater took a backseat, and ever since then cartooning has been in the front seat.

Switching gears slightly, I'd like to ask you about your influences. Stuck Rubber Baby has a completely different look as opposed to, say, Wendel, and definitely Barefootz. Who are your original influences, and have there been any recent ones?

Well, throughout my life there've been various people whose crosshatching abilities I admired. Robert Crumb is an obvious example. Jack Davis and his black and white work was a stunning crosshatch artist. Although, in later years he's done mainly wash and worked in color. Did you ever see one of those issues of Trump? The work he did in there was just him at his peak. Beautiful work, so he was someone I admired a lot. There have been others whose crosshatching, as a way of shading, I really appreciated.

The style for this book is complex. Not because I just decided I wanted to show off or anything because I really would've liked to have kept it much simpler, but the book demanded the kind of atmosphere that is a dark story that needed shadows. It needed a sense of weight and overcast skies and night shadows. Things that I just thought, "Well, I've got to put them in or the story will not fly emotionally." So, I was forced into this style.

Well, look at it this way: if someone wants to spend their time showing off their technique, and they're good at it, it's fun to look at. I'm mainly interested in the content. Whatever style serves is the style I'll go with. Basically, at heart, I'm a bigfoot cartoonist. I like the wild slapstick. Something like the purchaser's clearinghouse thing in Dancin' Nekkid [with the Angels; St. Martin's Press, 1987], to me that's just real fun cartooning, and if I could say everything I wanted to say in a style like that, that's the style I would stick with. Obviously, you can't tell "Jerry Mack" in that style, and you couldn't tell this story in the style of Wendel.

One of the things that surprised me most about the Barefootz collection was the essay in the back. I have a great deal of respect for you writing this. You essentially justify your usage of LSD, and its effect on you artistically. Did you find this to be a very difficult thing for you to do? I would imagine that you'd receive a mixed reaction to something like that.

Well, I didn't actually receive any reaction. I think it's because everybody's had me pegged as an old hippie for most of my career. I've been hoping about that-- well, [I] was doing underground comics where it was assumed that everyone was doing that stuff, and then I continued making references to it periodically over the years. I've been on the record on that so long that if I wanted to be secretive about it, it's too late.

A general policy I like to have is get it out, even if you wish you hadn't later, because then you don't have the option of being a coward. I did feel, particularly during the '80s, that the level of stigmatizing that went on, particularly about psychedelics, was not based on reality at all. I don't find something like LSD very compatible with the kind of difficulties and responsibilities of adult life and I haven't done it in a lot of years. I'd be disappointed if somebody said, "You'll never get to do it again."

But I don't know when I'll ever do it because it takes a certain amount of time and a certain amount of recovery time, and it's not a great thing to do if you've got a lot of practical anxieties going on. Adult life has been so full of practical anxieties that there's no place for LSD in my current life, but it was really good for opening my eyes to things. I think it should be explored more.

Anyway, I'd like to maximize the chances that people would use LSD in exploratory ways, and minimize the use of party drugs for very young people. I don't feel like years when you're basically forming your ego in the first place is a great time to be shattering your ego every weekend. I felt I've benefited from the fact that I had some life experience under my belt before I did it the first time. Not that I was that old, but it was my senior year in college. It took me a while to get to college, so I was about 22 or 23, or something, when I did.

I felt like I knew who I was enough that I could go off there into the stratosphere and come back and find myself again. I worry a little bit about someone-- I knew kids who were doing it at 14. I just wonder when you would have the chance to find yourself in the normal course of life, if you're doing-- I don't feel it's a harmless drug, but I feel like it has too many possibilities to be just outlawed.

Another thing about the Barefootz collection is that you eliminated all of the strips that featured Headrack as being gay. Did you feel that adding sexuality to any character other than Dolly would unnecessarily complicate the strip?

No, that has nothing to do with anything except chronology. Headrack didn't come out until the strips that I drew in '76, and this book only takes it to '73. It's always been contemplated that at some point, perhaps there would be a second, a companion Barefootz collection, which would take the strips from '74 through '79, which is when I stopped doing the series.[2] In those, all those strips would be used. I decided that Headrack was gay sometime around '72 but I had a long term plan for revealing that to readers.

One, I did not want to do the thing that was frequently done in liberal sitcoms in the '70s, where a peripheral character would be brought to center stage, or usually not even, someone who'd never been seen before would be brought on who would be gay. Then all the characters in the show would be liberal about it or if they weren't liberal at the beginning of the show, they would have been liberalized by the end of it. Then the character would go off and never be seen again. In which was basically the way Garry Trudeau handled Andy Lippincott [in Doonesbury] in his first appearances in the '70s. I didn't want to do that.

I wanted to have a gay character who was thoroughly central to the strip the way gay people are central to life. I wanted to have a number of strips about Headrack with emphasize to his role as friend to Barefootz before I brought up the fact that he was gay, so that readers would have to deal with it-- that's the character [with which] they had already bonded. Also, there was a period when underground comics almost went under in response to this 1973 Supreme Court decision on obscenity, which just created all sorts of hurdles for uncensored comics.

There was a big gap between '73 and '74, and then they started slowly climbing back a little bit in '74, and '75. I didn't have a lot of places to do Barefootz during that period. By the time when I did start doing Barefootz again, that's when I was trying to do strips and use Headrack and get readers used to him, having in mind that I would do what I did in '76, which was a strip about him being gay.

One last comment on Barefootz: What exactly is Glory and where can I get one?

[laughs] Look under your bed.

I understand you received the Stonewall Award for your contributions to the gay community.

Actually, Eddie and I as a couple jointly won that.[3] I was presumably doing comic strips of value to the gay community, and Eddie [won] for community organizing. It was, save the day, it was the final injection of money into the family at a time that we were teetering on the brink. It came with a $25,000 prize, half of which was Eddie's to do with his projects, and half which was mine, so that [was] $12,500 before taxes. I could add that up with my credit limits on credit cards and the money I could borrow on life insurance and every other resource that I had and finally say, "I have enough money to finish Stuck Rubber Baby. I can get it."

That had been the real nightmare during this extended period. For a while it looked like not only was Stuck Rubber Baby going to destroy me financially, but I would not be able to finish. I would simply run out of money and go bankrupt, and you can't borrow money if you've been bankrupt, and so what would I do to finish the book? Now it seems surreal how desperate the situation got and so when we got the award, and the way we got it, is just a step short of the old [The ]Millionaire show when God shows up from John Beresford Tipton-- did you see that in reruns?

That was back during the '50s. There was this wish fulfillment show where there was this multibillionaire named John Beresford Tipton, who at the beginning of every show he would dispatch his executive secretary to go into someone's life who'd been selected by some means, and just say an anonymous donor has given you a million dollars and the taxes have already been paid. It's all yours. Then the show would be about the effects it had on their life. We got a Federal Express letter one morning and inside it, it said basically, “We would like to give you $25,000, would you accept it?” [chuckles]

I remember Eddie was in the other room and he said, "What just came?" and I said, "Somebody wants to give us $25,000," and he thought I was joking. Most people would, but that's the way that occurred. We called up to make sure it wasn't a practical joke and then accepted.

When you started Gay Comix, there were several big underground anthologies at the time like Raw, Snarf and Weirdo. Were you trying to publish a side you felt wasn't fully reflected in comics at the time?

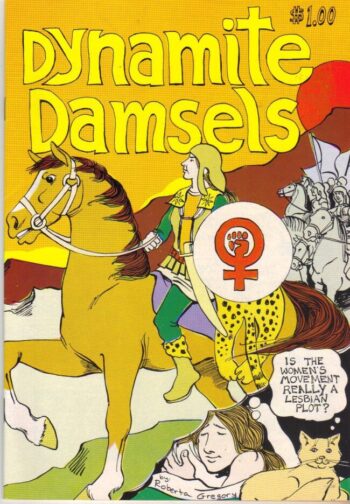

There had been some predecessors. There was a series called Gay Heart Throbs in the late '60s. Actually, it started coming out in '76, about the same time that I did my first gay story. It broke ground, but it was basically campy and it was playing gay for outrageousness. I felt that I'd like to do a comic which was actually about the lives that gay people actually live, done by gay people about their lives, not [comic] book gay men and lesbians. Two of the contributors to Gay Comix were Mary Wings and Roberta Gregory, who were actually the real pioneers.

They had published as early as '76. Something magic about '76. Everything was happening at '76 about gay characters and comics. Roberta Gregory put out her comic Dynamite Damsels and Mary Wings had two comics. One was called Come Out Comix and one was called Dyke Shorts.[4] I was so pleased I was able to get them involved because I wanted to make a statement: this is not just a male thing, I want this to be men and women. They were my inspirations, they did stuff that was really about everyday life. Even if you want to twist it, put it to a comic prism and exaggerate, that was fine. I wanted the things at Gay Comix to have heart, to not just be being silly. That was my goal.

I loved "Felix’s Friends". Have you ever considered doing a complete children's book?

Well, I would love to just because I love children-- because when I was a kid, I was a big Dr. Seuss fan. I wrote him fan letters and got nice letters in response when I was 15 years old. I wrote him again-- when I put [out] my first Wendel book, I wrote him again because I had come across in my files our exchange when I was 15, and there was a lot of publicity about him at the time. He'd just turned 80 and had done The Butter Battle Book, which spent ages on The New York Times Best Seller List. I wrote him a letter and I sent him photocopies of our exchange and said although I hadn't become a children's book artist like I thought I wanted to at that time, but I had become a cartoonist and was about to publish my first book.

His treating me seriously was something that meant a lot to me when I was 15, because he did. He wrote a letter, gave me just down-to-earth advice, artist to artist. He didn't condescend. That meant a lot. He wrote me once again a very, very warm letter. He's a person I always admired, but I'd love to do a children's book if I could. I understand they don't pay very well. I'm so scared of getting in another situation, inadequate advance. If I ever could sustain myself during the time it took to do wonderful illustrations, I would love to do that.

I couldn't help but notice that in the current Comic Book Legal Defense Fund letter, you're thanked. What's your involvement with the organization? Have you ever had a problem with censorship?

Oh, I've been cited. [laughs] All the best people have. I'm not one of the main targets for those things. I did this [short] called "Big Marvy's Tips on Tooth Care" one time. It was a little dental hygiene [story] about brushing your teeth with your own cum and gave instructions on jerking off and putting it on your toothbrush and stuff. That one I saw in the news mentioned, [as] one of the reasons why this bookstore got busted. I haven't personally had a lot of challenges, other than just the fact that it's hard for something like Gay Comix to get across borders sometimes. I'm a believer in-- I'm a First Amendment absolutist, as they say. I did a drawing, where I did the Howard Cruse version of drawing by, what's his name? The guy in Florida.

Mike Diana?

Mike Diana. Took a Mike Diana drawing. I'll show it to you, and did-- actually, I showed one of his drawings in a jail cell, and allowed them to make prints of it. They sell to raise money. Eventually, I will offer the original artwork for auctions but I want to wait until there's enough of a market for my work. If it would bring a good price. It's the second thing I've done for them over the years.

I want to ask you a little about the strip, "Raising Nancies". It's a very, very bizarre story. How did you come up with that?

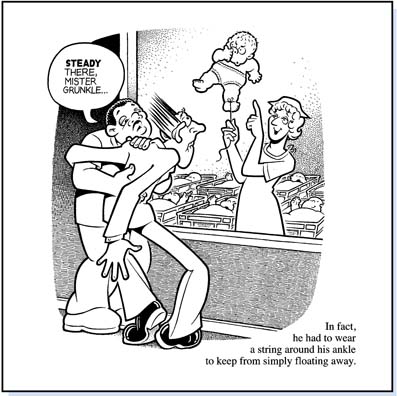

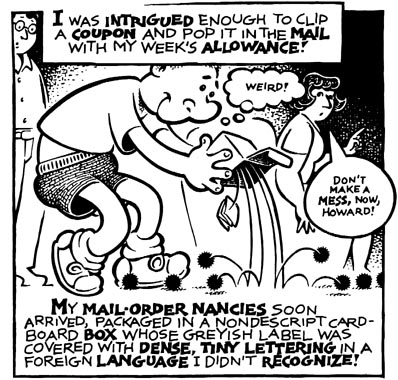

Well, that's just one of the notions that occur to you. The way the creative process works, things are mixed together. Back in the early '60s before they made psychedelics illegal, you could order peyote from ads in the back of Esquire. They had small ads and people at Birmingham-Southern were doing it. They'd send them in, get [a] little box of cactus and trip out. That got mixed in with this notion of just how-- that weirdness of the whole concept of the character of [Ernie Bushmiller's] Nancy. It never really seems like a person, a being [that] had this weird look to her, and somehow those came together with the notion of-- oh, and there was also, people would order these little plants that you'd put in a glass of water. There were ads in comic books. I think maybe they still do. So all that gets mixed together and it turned into this little takeoff on animal rights. The rights of sensibilities at the end. It's very strange.

[laughs] One last thing: the inevitable question is, what now? After devoting four years of your life to this book, will you be going back to Wendel, or do you have plans for another novel?

Oh, neither. [laughs] Another novel would be out of the question until I could work out a way to do it without putting myself in a hole the way this one did. Also, I'm not just a person who wants to do novels. This was a chance to see what I would do with that form. I was always curious, having always worked in the short form, what would I do if I could do the long form? That answered that question. I use things that have been simmering in the back of my mind without that a good place to present themselves for years. Sure, [there are] a few other ideas for major works of art that are in the back of my head, but none of them would be practical to do right now.

As to Wendel, what I would like to avoid doing if I can manage it is setting myself up for another situation where I have to provide episodes regularly, and where my life is dominated by that one feature. That was the reason I quit in the first place, because I was never able to do other projects because Wendel took up all of my time. I do love the Wendel characters and I'd love to have opportunities to do Wendel stories. Do complete stories that were not part of a series. By now, I don't know if any of the markets that could pay, what it'd cost me in time to do those. That's held in advance until I could get some work that pays enough that it can subsidize projects that I do as labors of love.

That's usually throughout my career, the way I got a lot of things done, the underground comics stuff. I was able to do them because I was getting advertising work-- oh, not advertising, but illustration work. Other kinds of commercial work that would pay enough to do the job in three or four days, and it would be enough money for a couple of weeks. Get a few of those jobs, and you've got enough clear time that you could do a comic book story for $25 a page and it's not a problem, but I haven't. I've been out of the freelance illustration market so much that I can't just snap my fingers and get those kinds of jobs the way I used to. This is an example of logistical problems that life as an artist presents.

My last thing is, do you still dream of Dancin' Nekkid with the Angels?

[laughs] Well, that just stands for one view of the alternate afterlife or experience or ecstatic transport. Dancin' Nekkid with the Angels is constructed in a [sense of] youthfulness to aging today. There is a structure to the book. The last two stories, the [death] strip and the purchaser’s clearing house, are variations on the theme of, "I may be miserable now but someday I'll get what I need. I'll get all this joy." In one case, it's the joy of all that money or being taken care of at some mythical place. That's the purchaser’s clearing house, it'll take you in. Or in the death strip, in that case, the strip ends with an unexpected flip, [with] the rest of [the story] being a deconstruction of all our ideas about death that are all based on [how] the body will deteriorate everything. The worms will eat us. But then it says, "Don't worry, we'll all go to heaven." I'm not traditionally a religious person, but I do tend to think that if any consciousness exists after death, it will probably be a happy experience.

* * *

EDITORIAL NOTES

[1] The acknowledgements to the 1995 edition of Stuck Rubber Baby identify a Leonard Shiller of the Antique Automobile Association of Brooklyn as the person responsible for aiding Cruse in the photographing of classic cars; supplementary materials to the 25th Anniversary Edition in 2020 expand on the same Leonard Shiller's contributions. It is uncertain whether the "Scott" referred to by Cruse is a nickname for Leonard Shiller, or a different person, or simply a misremembered name.

[2] Later Barefootz strips were eventually reprinted in The Other Sides of Howard Cruse (BOOM! Studios, 2012).

[3] This prize was awarded in May of 1993. It is not to be confused with the Stonewall Book Awards, in which Stuck Rubber Baby was a Literature Finalist in 1996.

[4] Come Out Comix was actually published a little earlier, in 1973. Dyke Shorts was published in 1978.