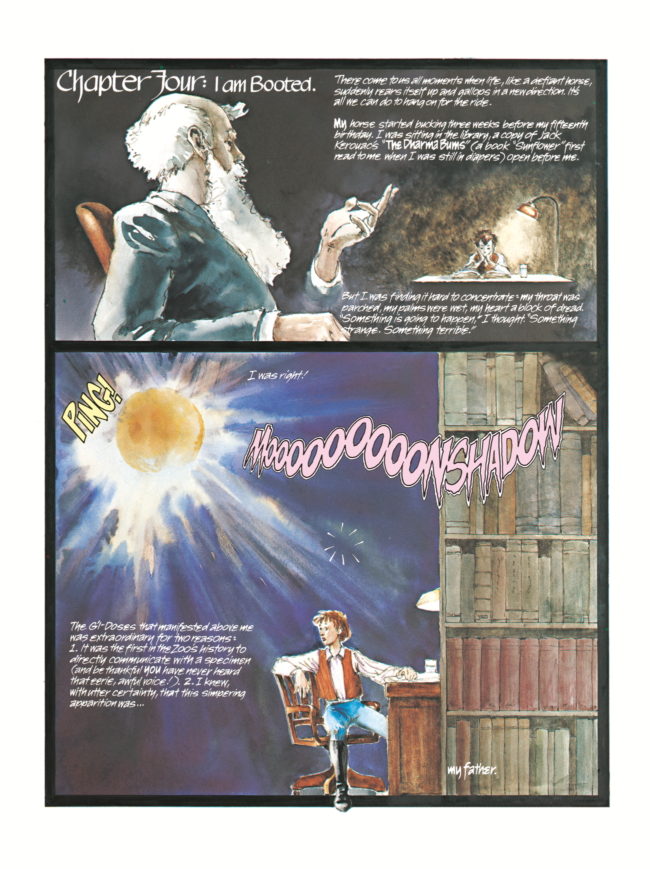

J.M. DeMatteis has been writing so many kinds of comics for so long, its hard to remember a time before that was the case. He has long been considered one of the all time great writers in North American comics, but to his mind, he found his voice in writing Moonshadow, a definitive edition of which was just published by Dark Horse. Originally a twelve issue miniseries published by Marvel’s Epic imprint in 1985-87, it was re-released by Vertigo along with a sequel Farewell, Moonshadow, a decade later. Painted by the great Jon J Muth, with additional work by Kent Williams, George Pratt, Sherri van Valkenburgh, and Glenn Pepple, and letters by Kevin Nowlan with Gaspar Saladino, it remains a singular work in the history of North American comics.

J.M. DeMatteis has been writing so many kinds of comics for so long, its hard to remember a time before that was the case. He has long been considered one of the all time great writers in North American comics, but to his mind, he found his voice in writing Moonshadow, a definitive edition of which was just published by Dark Horse. Originally a twelve issue miniseries published by Marvel’s Epic imprint in 1985-87, it was re-released by Vertigo along with a sequel Farewell, Moonshadow, a decade later. Painted by the great Jon J Muth, with additional work by Kent Williams, George Pratt, Sherri van Valkenburgh, and Glenn Pepple, and letters by Kevin Nowlan with Gaspar Saladino, it remains a singular work in the history of North American comics.

Since then he has continued to write superhero comics, ranging from Spider-Man: Kraven’s Last Hunt to philosophical, thoughtful superhero tales that play with the genre, from Doctor Fate to The Life and Times of Savior 28, and perhaps best in The Spectre, to hundreds of light hearted adventures with Keith Giffen like Justice League International. He’s written comics for younger readers including Abazad and The Stardust Kid with Mike Ploog, and The Adventures of Augusta Wind and its sequel with artist Vassillis Gogtzilas. DeMatteis wrote a very different kind of autobiographical comic with artist Glenn Barr in Brooklyn Dreams. He’s one of the people who defined the Vertigo line – both by writing comics for the imprint like Mercy, The Last One, and Seekers: Into the Mystery – and for his earlier work for Marvel’s Epic imprint like Blood that showed there was an audience for thoughtful adult comics. If there is anyone who has defined what modern comics can be – which is to say, almost anything – it is DeMatteis.

In the past year he’s written two very different projects, Girl in the Bay and Impossible Inc. for Berger Books/Dark Horse Comics and IDW, in addition to the new hardcover edition of Moonshadow, which to my mind remains one of the best comics ever made. I thought that when I first read it as a teenager when Vertigo reprinted this “fairy tale for adults” and it holds up on rereading all these years later. I’ve spoken with DeMatteis in the past and he has kindly listened to my praise about the book over the years, and we spoke recently about how he found his voice in writing Moonshadow, the power of stories, and my very different reaction upon rereading the book.

I wonder if you could set the scene a bit. You had been working at Marvel and DC. You co-created I, Vampire and Creature Commandos, and written acclaimed runs on Captain America and The Defenders. You had this idea for a creator owned fantasy maxiseries about life and innocence and existence – and Jim Shooter said, sure, we’ll publish that?

I wonder if you could set the scene a bit. You had been working at Marvel and DC. You co-created I, Vampire and Creature Commandos, and written acclaimed runs on Captain America and The Defenders. You had this idea for a creator owned fantasy maxiseries about life and innocence and existence – and Jim Shooter said, sure, we’ll publish that?

Actually, the first place I went was to DC. My contract at Marvel was wrapping up and I was considering going back over to DC, where I’d started. My friend and mentor, Len Wein, offered me Justice League and Swamp Thing (pre-Alan Moore). Karen Berger was very interested in doing Moonshadow and she even mentioned a new British artist—some guy named Dave Gibbons—as a potential collaborator. I ultimately decided to stay at Marvel if I could do Moon and the Greenberg the Vampire graphic novel. This was the period when creator-owned comics were just poking their heads out of the sand and I really wanted to do something that took me out of the superhero comfort zone. Jim Shooter was approved both projects, then pointed me to Archie Goodwin, who was overseeing Marvel’s Epic line.

What was the late Archie Goodwin like and what was the process at Epic that he had set up?

Archie was a delight. Low key. Very smart. Immensely likable. And, best of all, he gave creators all the room they needed to pursue their own creative vision. I also have to tip my hat to our two editors, Laurie Sutton and Margaret Clark, who never interfered, let us tell our stories in exactly the way we wanted, but were always there to offer their help every step of the way.

How did Jon J Muth end up working on the book? How much had he done in his career before this point?

If I’m remembering correctly, Jon had done Mythology of An Abandoned City for Epic Illustrated, although I hadn’t seen it. I met Jon through our mutual friend Dan Green, who’d passed my original Moonshadow outline along to him. Jon was very excited about the project and, as soon as he showed up at my house with some initial sketches that visualized the story and its tone perfectly, I knew he was the artist for Moonshadow.

What does the song Moonshadow mean to you?

I was a huge Cat Stevens fan back in the day. His songs were often about the inner search, the grasping for truth and meaning that’s so much a part of our story. That said, much as I like that particular song, it didn’t have special meaning for me. I was just looking for a name that evoked the feeling of the tale. The kind of name a hippie mother would bestow upon her son. I remember flipping through my albums, looking at song titles, stopping at “Moonshadow" and knowing that was it.

My original title for the story, when I first envisioned it, long before the Epic series, was Stardust—which I used, years later, for my all-ages series The Stardust Kid.

In the back matter to this “definitive edition” you have a list that you made of some of Moonshadow’s favorite books. Having read the book so many times, I can’t help but think these are books that have meant a great deal to you, as well.

Some of them were definitely books near and dear to my heart. But some were books I was seeing through the character’s eyes. So it was a mixture of my favorite books and Moon’s! And some of his later became mine.

It sounds like you had this very clear idea of who Moonshadow was and the feel and sensibility of this story early on. Where did Ira come from? In the notes you include in the back he sounds fully formed, but named Klikker.

In the beginning, Ira was kind of a classic cranky sidekick—inspired by characters like Jack Kirby’s Oberon and Jim Starlin’s Pip the Troll—but he quickly became his own unique creature, incredibly important to the story. In many ways, perhaps even more than the G’l-Doses, Ira embodied the philosophical contradictions that the story addressed, the idea that, as Dostoyevsky said, “good and evil are monstrously mixed up in man.” Ira was, in many ways, a terrible person; yet there was always something good and decent trying, and often failing, to get out. There was no real reason for Moonshadow to love him, and yet he did. And, in some ways, that love redeemed Ira.

As for the name change: I had an old friend named Ira—who had nothing in common with his fictional namesake!—and I thought it was a very funny to name an alien after a Jewish guy from Brooklyn.

You mentioned meeting Jon J Muth through Dan Green. At the same time you and Muth were making Moonshadow, you were making Doctor Strange: Into Shamballa with Green. This was at a time when painted comics were still unusual. Did that aspect of how the comics would look, how the artists thought about design and color, affect the way you worked?

The painted aspect opened up the stories in new ways, adding depth and texture and a deeper sense of wonder to the art.

I don’t think painted art is necessarily better than traditional line art, it’s just different—it’s almost like the difference between traditional animation and CGI animation—but I think the painted look was essential for both these projects, a way to announce that we were doing something unique. It also helped that Jon and Dan knew how to really breathe life into painted comics. I’ve seen other artists use the painted approach and the result can be incredibly stilted. Sometimes the art gets so hyper-real it becomes completely fake. But Jon and Dan were, and are, masters. They never lost the flow and energy that comic books require.

At the time we were working on Moonshadow and Into Shamballa, Jon and Dan were sharing a studio, so I’d visit them and Dan would be at one table painting Doctor Strange and Jon would be at another bringing Moon’s universe to life. We were all good friends and there was a real sense of creative community, and creative joy, permeating both projects.

How lucky was I to be working with two such brilliant artists simultaneously?

I remember the first time I read Moonshadow thinking that this was a young man’s book. This was your first and possibly only chance to tell this massive story that had been building for years and it has this incredible energy.

Years ago I read a quote that essentially said, “Whatever story you’re writing, treat it as if it’s the only story you’ll ever write. Fill it with all your passions, hopes, dreams, fears. Everything you are.” I’ve searched high and low over the years for the source of that quote and I can’t find it—and at this point, I’ve probably mutated it so much that I can claim it as my own—but that’s exactly what I did with Moonshadow. It was, as you suggest, a creative explosion. A chance to stop “writing comic books” and just write. Be myself. In the process, I found my voice as a writer.

Of course having Jon’s incredible art to inspire me didn’t hurt. I don’t know if we’d even be talking about Moonshadow today if Jon hadn’t been the illustrator. If the story worked it was because of a creative fusion between us. I knew that, working with an artist of his brilliance, I had to up my game. I hope I inspired him as much as he inspired me.

As I think I’ve said in our previous conversations, I think this is one of the great comics. Period. But I will admit that re-reading it again for this interview, I found myself sometimes thinking, it’s a very wordy book.

You have no idea how much copy I cut out of that book! I’d write a page and then start slicing and dicing. That said, comics aren’t one thing or another. They’re anything we want them to be. And with Moonshadow—and a number of other projects I’ve done over the years—I wanted to explore the line between prose and comics.

There are some people who say that comics should be “movies on paper.” And they can be that. But they can also be a thousand other things. Want to do three of four pages that are essentially illustrated prose and then shift into more typical, or perhaps even wordless, comics? Why not? Don’t let the format lead you, let the story lead you.

When Muth and I reunited, ten years later, for Farewell, Moonshadow, we essentially did an illustrated prose piece broken up by wordless comics sequences. And I think it’s some of the best work we've ever done, together or separately. Is it a comic book in the traditional sense? No. But it’s a comic book because, well, we say it is.

I kept thinking that one way you were using the quotations and some of the references was that you were trying to place the series into a framework. That in superhero comics, you had previous runs or creators you have callbacks to in different ways and here you were trying to find a way to do that here in a comic that people might not know what to make of.

Not consciously. But I do think the quotes put the series in a more literary tradition instead of a strictly comics tradition. But, again, I wasn’t thinking that. I was just following the story, following Old Moonshadow and writing what he told me to write. In the end, he controlled the story, not me. And I really mean that.

There was a point, toward the end of the series, where I realized that Old Moon wasn’t necessarily telling me the truth. I’d taken him at his word till then, believed that this had been his life. But toward the end I began to suspect that he was mythologizing his life just as I’d been mythologizing my own.

Writing stories is a strange and wonderful thing.

So many of your stories – possibly all? – are about people born into circumstances, a system, who reject that way of thinking. Who reject the story they are told about themselves, even though it might be easier to believe it. Moonshadow, his mother and Ira all faced that.

So many of your stories – possibly all? – are about people born into circumstances, a system, who reject that way of thinking. Who reject the story they are told about themselves, even though it might be easier to believe it. Moonshadow, his mother and Ira all faced that.

We write about the things that obsess us. The themes in a writer’s work are the themes of a writer’s life. The Big Theme that has always obsessed me is the search for meaning, for personal, and cosmic, identity. Who are we? Why are we here? What’s the meaning of it all? Exploring those ideas, from both a psychological and spiritual perspective, is the driving force behind many of my stories, whether they’re more personal projects like Moonshadow or more popular ones like Spider-Man.

Part of that search is questioning what we know—or believe to be true—about ourselves and the world around us. And those beliefs—those stories we're told about ourselves, as you put it—often have to be exploded in order to find a deeper truth.

All that said, people often forget that, philosophical concerns aside, Moonshadow can be a pretty goofy book, with a Pythonesque sense of humor running through it. Yes, we grappled with the Big Issues, but this is also a story where Moon and Ira escape death by farting their way to freedom!

As you mentioned, besides reprinting the original series, Vertigo published a sequel Farewell, Moonshadow. Why did you want to make a sequel at all?

I’d thought about a sequel when we were doing the series for Epic and conceived the basic idea of Farewell then. For reasons that escape me now, we decided not to do it, but I held on to the idea and, when we brought the book to DC, pitched the sequel to Vertigo chief Karen Berger and our editor Shelly Bond, and they both responded enthusiastically.

As for why I wanted to do it: Moon’s story was the story of an adolescent stepping into adulthood. It was also the story of Moonshadow achieving a kind of enlightenment. But what happens after enlightenment, when you come back down from the cosmic high? What happens when the boy becomes a man and has to assume the burdens of the adult world, bringing along all the baggage—good and bad—of his strange, dysfunctional childhood? Those were the questions I wanted to explore (perhaps not consciously at the time but, looking back, it’s very clear to me.)

You and Jon J Muth clearly wanted the sequel to look and feel very different from the first series. Was some of that because of the realization you mentioned, that the character wasn't telling you the truth but his own mythology, which gave you permission of a sort to go in a different direction.

Right. As I said before, Old Moonshadow was a highly-unreliable narrator—I really felt as if I wasn’t so much writing the story as transcribing the story Old Moon was telling me—and, toward the end of the series, I suddenly realized that much of what he was telling me was distortion, a fairy tale version of his life. So Farewell was an attempt to move beyond the fairy tale and cut closer to the bone. (In the end, I think we moved from fairy tale to allegory.)

I also wanted to keep stretching as a writer, so I knew that doing the book in the same way would be redundant. That’s why I conceived the idea of doing what was essentially a long prose piece with full page illustrations, broken up by silent comics sequences.

In many ways, I think the sequel is even stronger than the original series. It’s certainly some of the best writing I’ve ever done. And Jon’s art, always brilliant, reaches a real peak in Farewell, Moonshadow. You could do a gallery show of his full-page illustrations. They’re wonderful.

Working with Muth on these two projects – I think of them as related but two different beasts, I don’t know how you think of them – I’m curious about the process of Farewell, Moonshadow and working with Jon and Shelly Bond and Karen Berger. I said before that Moonshadow was a young man's story, and this felt like the work of a different creator, an older more mature creator.

I totally agree. You grow and change tremendously in ten years. Life throws all manner of weirdness at you. You lose things you hold dear, you fall, you get back up again. Find new hope, new life. I’d certainly been through my share of personal melodrama in the decade between Moonshadow’s completion and the writing of Farewell and the story reflects that.

The original series is about the journey from childhood to adulthood, both psychologically and spiritually. Farewell, Moonshadow is about the unfolding process of holding on to that growth and wisdom. Living it. Having a cosmic revelation is one thing, but how do you hold on to that, how do you not forget, while you’re dealing with the sometimes-painful challenges of adulthood, of the so-called “real” world?

As for working with Karen and Shelly: They’re two of the best editors, and nicest people, in the business. My respect for them both is off the charts. Karen’s one of my oldest and dearest friends and Shelly became a good friend as we worked together on a number of Vertigo projects, so creating Farewell, Moonshadow was a delight.

You cited the creative fusion between you and Jon as part of the book's success. And you've worked with a lot of artists over the years. Do you think that the best projects require that kind of understanding and spark? You seem to be very skilled at writing for artists – with artists? – in a way many comics writers are not always.

Comics are about collaboration, about chemistry between writer and artist, and that’s something you can’t create. It’s either there or it’s not. I’ve had projects where I’ve written a terrific script, the artist has done an equally-terrific job, and yet there’s no creative “click,” the chemistry’s not there, and the story just falls apart. But when that “click” happens, it’s truly magical and that magic infuses every aspect of the project. Jon and I certainly had that when we were working on Moonshadow and I am forever grateful.

What was the response to the book when it first came out? I remember when Vertigo re-released the book it was described as a "fairy tale for adults" and Epic was putting out a lot of really great work. It was coming out when indie comics were publishing some great work, but there's no book quite like it.

My memory was that it was very well received. Certainly the best-received work I’d ever done. It didn’t fly off the shelves the way superhero comics did, but I don’t think anyone expected that of an Epic book. Moon hit a very specific audience—a kind of pre-Vertigo crowd—that took it to their hearts.

The “fairy tale for grown-ups” label started at Epic. I believe it was on all the original ads. Our way of saying that this story isn’t for kids. But there was still some pushback when the book came out; some people were still expecting a “Marvel Comic” and they were shocked by some of the content. Which doesn’t seem remotely shocking in today’s pop culture landscape. I think, eventually, they simply labeled it “for mature readers."

I wonder if you could talk a little about Brooklyn, not today’s borough, but where you were born. Because it’s played such a big role in your work.

I think if I’d been from Peoria, then that would play a big role in my work. We’re always looking back at our roots and that’s where my roots are, in the Brooklyn of a certain time and place. Working class families living in apartment buildings. Swarms of kids playing on the streets. Teenagers coming of age while the world around them exploded with drugs and protests and consciousness-expansion. It’s a world, and an era, I explored again recently in my Dark Horse/Berger Books series The Girl in the Bay. I guess Brooklyn is like a shadow. If I look behind me, it’s always there in some form.

What was it like re-reading the book a decade later? Do you typically read your work after you’ve finished writing it or do you just put it on the shelf and admire the binding? Did you read it again for this new edition?

I read it over after it comes out, but then it usually goes on the shelf and I might pull something down and reread it years later.

With enough time, there’s a certain level of objectivity when I look at older work. It’s almost as if someone else wrote the stories. With some projects I can see every blemish and flaw and I’m embarrassed by how uncooked my writing was. And sometimes I look back in amazement at the quality of the work. With Moonshadow it’s the latter. With each issue I was stretching, growing, becoming something new. Would I write the story the same way today? Probably not. Would it be as good if I wrote it today? Probably not. Because it was a reflection of a specific time in my life, the specific person that I was then. And also the reflection of that creative fusion with Jon J Muth. The book came together in an almost magical way and I’m so grateful to see it back in print.

Speaking of artists you’ve worked with, you’ve collaborated with Mike Cavallaro a few different projects in recent years. You clearly have a very good working relationship and I wonder if you could just talk about the relationship that the two of you, and working together on different kinds of projects.

Speaking of artists you’ve worked with, you’ve collaborated with Mike Cavallaro a few different projects in recent years. You clearly have a very good working relationship and I wonder if you could just talk about the relationship that the two of you, and working together on different kinds of projects.

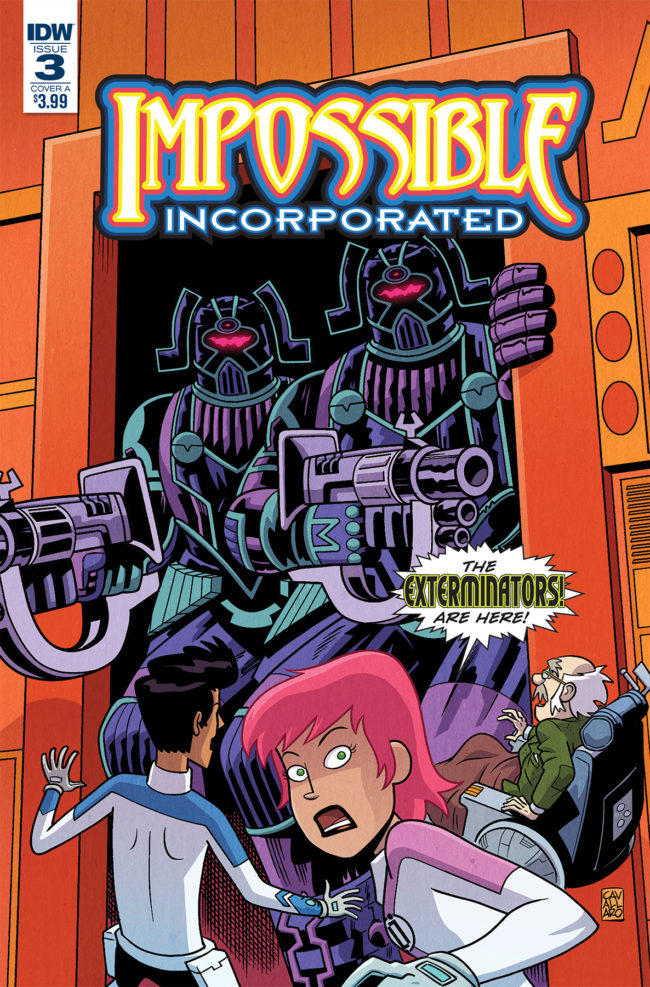

About twelve years ago a mutual acquaintance gave me some of Mike’s self-published comics and I was blown away the the skill, imagination and energy of his work. When Mike and I finally met up, I discovered that he was as nice as he was talented, and we just clicked, creatively and personally. We’ve worked on a number of things over the years (along with Impossible Inc., our other recent project was a contribution to Image's Where We Live anthology) and, despite the fact that Mike can write, pencil, ink, color and letter with the best of them – which, in some people, could lead to an explosion of ego – he’s as easygoing a collaborator as I’ve ever had. Whatever kind of story I throw his way, Mike adapts his style to suit the material yet always retains his artistic identity, not an easy feat. We’ve developed a mutual trust and respect that informs everything we’ve done together. And, I hope, everything we will do in the future.

As far as bringing older projects back into print, is there a chance we’ll see a definitive edition of Blood one of these years? I’d also love definitive or at least new collections of your run of The Spectre, Doctor Fate, The Last One, Doctor Strange: Into Shamballa, and Green Lantern: Willworld, for those listening…

Now that Moonshadow has found a home, we’re going to focus on Blood next. As for the others you mentioned: The Last One was reprinted a few years back, but Dan Sweetman and I are now looking for a new publisher. Into Shamballa has been printed around the world – there was a new hardcover edition in Italy just last month – but not in the U.S., which, frankly, baffles me. (“Hello, Marvel…?”) And, yes, I’d love to – finally! – see collections of my Doctor Fate and Spectre runs, as well as a new edition of Willworld, but that’s not in my hands. (“Hello, DC…?”)

You described the act of writing this as you finding your voice as a writer. I can’t help but think about how you write so many things and in so many tones and approaches and styles and genres – and how that happened since Moonshadow. I mean in the past year you’ve written two very different comics (The Girl in the Bay and Impossible Inc.) and an animated film Constantine: City of Demons. What are you drawn to and thinking about now?

You described the act of writing this as you finding your voice as a writer. I can’t help but think about how you write so many things and in so many tones and approaches and styles and genres – and how that happened since Moonshadow. I mean in the past year you’ve written two very different comics (The Girl in the Bay and Impossible Inc.) and an animated film Constantine: City of Demons. What are you drawn to and thinking about now?

It was wonderful working on The Girl in the Bay and Impossible Inc. at the same time because they are, as you say, very different: one is a twisty, very adult supernatural thriller and the other is an all-ages cosmic adventure. But I like to think that, at their hearts, they’re both very reflective of the themes and ideas that have permeated my work all along. The Impossible Inc. trade came out recently from IDW and the Girl in the Bay collection will be out at the end of August from Dark Horse/Berger Books.

As for what’s coming, I’ve got two more, not-yet-announced animated films in the pipeline (one of which will, like City of Demons, premiere, in edited form, on CW Seed), a couple of episodes for the upcoming seasons of Marvel’s Spider-Man, as well as two shorts that will accompany upcoming Warner Bros/DC animated films: Adam Strange and Neil Gaiman’s Death. As for comics, I’m working on an original project for, well, I can’t say yet, but it’s unlike anything I’ve done before, which makes it both fun and challenging. I’ve got other originals that I’m currently seeking a home for.

What else would I like to do? I’d love to do sequels to both Impossible and Girl in the Bay. I’ve been thinking lately about another novel—my kids fantasy, Imaginalis, came out almost ten years ago—and I’ve been juggling a few ideas in my head. Music? Absolutely. It’s long past time I did more recording: I’ve got a huge backlog of songs and there are few things I enjoy more than being in the studio. So many things! We’ll see which ones manifest in the world.

While I loved Moonshadow the first time I read it – as I’ve told you a few times over the years – what I didn’t say was that when I read Farewell, Moonshadow when it came out, I thought it was beautifully painted, but, eh. I reread it for the first time for this conversation, and I cried. Now that I'm in my thirties, I understand it in ways I never would have as a teenager.

I think that goes back to what we were saying before. Moonshadow is a coming of age story, Farewell’s concerns are different, more focused on the challenges of adulthood. Perhaps we have to live those challenges in order to fully appreciate the story? But that’s true of so many stories. You read something when you’re eighteen, you may even love it, but then you come back to it ten or twenty years later and you see layers and levels that you didn’t notice before, because you hadn’t lived those things yet.

That said, I believe there’s a basic truth, a fundamental wisdom, that we all have access to, whatever our age. And when literature addresses those truths, we can all relate because it’s not something we learn, it’s something we are. And stories, at their best, can remind us who we really are, as opposed to who we think we are.