An established provocateur from an early age, John “Derf” Backderf is a renowned comics creator residing in Cleveland, Ohio. His work has garnered much critical acclaim and has earned such accolades as an Eisner Award (Trashed) and an Angoulême Prize (My Friend Dahmer). His latest work, Kent State (Abrams Comicarts) is an in-depth and critical look at the events leading up to May 4, 1970 at Kent State University. A time of great change and political unrest, Backderf manages not only to encompass the many political and often volatile viewpoints of 1970s America, which lead to the tragic events of the Kent State Shootings, but he also manages to construct a nuanced and personal narrative from the victims’ point of view. Fifty years later, the echoes of this unrest, political and personal strife, are still felt nationally and internationally. At the time of this interview (June 2020), the world is in the grips of the Covid-19 pandemic and in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests in response to the death of George Floyd. The derailment of this narrative’s initial release date of April 8th, 2020 does not diminish its current and future value as a historical documentary and warning cry against the destruction of aggressive, hyper-partisan politics. In this interview, Backderf discusses his body of work and answers questions about his creative process, the nature of political cartooning and long-form cartoon journalism, the reliability of source materials, creating characterizations, thematic undertones, and the changing roles of media and technology in political activism.

This interview has been edited and condensed from its original form for the purposes of clarity.

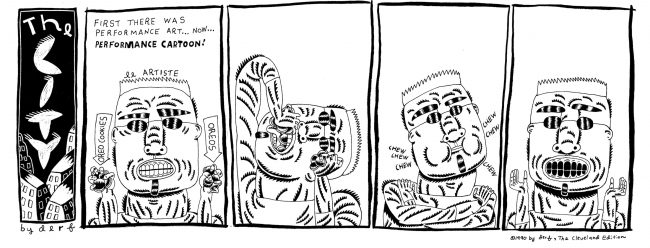

Let’s start with your earlier work. Tell me about “performance cartoons.” How did this strip become a recurring part of The City, and how do you use the performativity of comics to your advantage when storytelling?

That one was from my first year doing the strip and really represents what I was trying to do, melding counter-culture with pop culture and offbeat humor. The original concept of The City was that I wrote about what I saw around me. I went to an evening of crazy performance art and wrote that strip the next day.

With The City, I finally found my voice, after a decade of struggle. As my hero, Joe Strummer, said, “It’s an amazing thing to be in the right place at the right time with the right shit.” I felt like that, not to Strummer’s level, obviously, but for the first time, people were talking about my comics, especially here in Cleveland. And that’s a real rush when it happens. Yeah, some may scoff at that. Cleveland. Big deal, right? It’s Cleveland! But it’s always been important for me to matter in my own city. I started here, then spread out across the country, but I was always writing about Cleveland and Ohio.

The “performance cartoon” strips themselves, and other strips in a similar vein, didn’t necessarily have a point. They were just weird and fun. Confusing the reader is funny in itself, if you do it right. I’ve never liked obvious humor. Early on, The City was really off the wall like that, then it tightened up on me, unfortunately.

Tell me about the difference between structuring a ‘performance’ in the space of a four-panel work like The City, as opposed to a long-form narrative like My Friend Dahmer or Kent State.

Yeah, it’s night and day. Writing a strip, especially a freeform one, you’re shooting for a mood and a beat. It’s the look of the art and the vibe of the strip. There’s not much room, obviously, in just four or five panels, for a lot of nuance, even though weekly strips were printed quite large back then. I’d usually come up with the punchline or walkoff, and then write the three panels leading up to the last one. A good strip would have several laughs in it, not just the punchline.

When I started doing longer narratives later in the Nineties, there was a much bigger learning curve than I expected. I had to change my drawing style, and the writing is completely different. The City wasn’t a character-driven strip for one, and my books are totally character driven, so dialogue plays a much bigger role. I had to think about plot structure and pacing and all the things I never bothered with in a comic strip.

But once I dove in, y’know, it felt right. My books are a lot better than The City, I freely admit that, and the response from readers has been much greater. It turns out that long narratives are what I should have been doing all along. Wish I’d had come to that realization sooner.

Do you apply the same considerations to comic strip narratives as you do long-form narratives, if not, what are the differing considerations you make for each?

No, they’re completely different. Mine wasn’t a continuing story, like Lynda Barry’s. Each strip was self-contained.

The narratives are a lot more complicated in books, with multiple layers and threads. I’m not locked in to four panels, I can take it as long as I want to, and let the story go where it wants. I can pause the action, or vary the pace. A comic strip was kind of a mad /sprint to the punchline.

The City was always right here, right now, in the moment. I wrote a strip and it was in print a day or two later. That immediacy was unique to newspaper cartoons and something I really enjoyed. I felt like I was part of the zeitgeist. And that’s also why some of those strips are unreadable now. You had to be there. But a comic strip was also disposable. It was a free weekly, and when the reader was done with it, they tossed it away or left it on the train seat. We printed 100,000 copies a week, but no one saved them, except the rare one that got pinned to a cubicle wall at work. There were people who picked up the paper just for my strip, but there were also lots of readers who weren’t particularly comics fans, who would glance at the strip while flipping through the paper. Otherwise, they didn’t read comics.

You have to buy a book. You’re not going to just stumble over a pile of them stacked up in the doorway of a coffee shop. It’s a different relationship between cartoonist and book reader. The potential readership was a lot greater in newspapers. At my peak in the late Nineties, the collective circulation of all 75 papers I was in, almost every big city in the country, was something like 3 million… every week, week after week. How many read the comics? Unknown. But those that did were more casual fans than those of books.

Now, I could certainly lure people into comics. I used to do cartoon covers for the Cleveland rag. I did 50 or 60 of them in the Nineties. The circulation guys always told me that these “Derf Covers,” and that’s what they started calling them, which were basically front-page versions of The City, resulted in a significantly higher pick-up, meaning there weren’t copies still rotting in the rack after the weekend. So maybe I generated some interest in comics where there wasn’t any before, and then they’d start reading the other strips in the paper, and they were all great strips.

Do you find it easier to experiment with the comics form in strip work? Or do you find it more restricting than longer form narratives?

Oh, I was a lot more experimental with the comic strip, especially early on, say the first five years. I was twisting and pulling the form in all kinds of ways, just seeing what worked and what didn’t. The art blew out of panel borders. Perspective was bent and jagged. It was all very post-punk and expressionist. I had a lot of fun with it and weekly papers were open to experimental comics then. By 2000, that changed.

When I first tried long-form comics, around 1995, that was an effort to mix things up and see what I could do in a different genre. I felt like I was getting a bit stale with the comic strip.

Curiously, even though it started technically as an experiment, my books are composed and drawn very traditionally.

And once I started making books, I lost the ability to write strips. I just couldn’t think in four panels anymore. I encountered a similar dilemma when I went from single panel cartoons, which was my first genre in the Eighties, to strips.

What kind of stories does a short strip allow you to tell that perhaps a longer form comics narrative may not?

The “True Stories” are a good example of that. The City only had a couple recurring features, but “True Stories” were a constant throughout its two decades. I did one or two a month. These were the heart and soul of the strip. They were these short observational comics, just little episodes of weirdness I encountered in my travels around Cleveland. They could be funny, or puzzling, or sad, or make no sense at all. They still hold up, too, while the rest of The City is quite dated.

The “True Stories” worked beautifully in four panels… but you can’t make a long narrative out of them, because they were only fleeting moments. The best “True Stories” left a mark with readers though. So that’s the power of short narrative.

The City strips feel quite conversational and interactive with reader. Can you tell me about creating that casual observational tone throughout works and images in The City, as opposed to perhaps the more objective or documentary tone of works like Kent State?

That’s a good observation. The strip was created in a coffee shop. Me sitting in a corner table in 1989 scribbling in a sketchbook. I’d eavesdrop on other customers, and talk to friends when they passed through. This was long before the internet or cellphones, so there was lots of chatter. So yeah, it began as conversations, and when the strip coalesced, that component stayed with it. I always wrote it as if I was having a conversation with the reader in that same coffee shop.

My books aren’t that way. I’m creating a little world there and presenting it to the reader. There’s no conversation between us.

Both your comic strip work and your long-form graphic narratives have a political bent. Is there a difference in the kind of political issues you can tackle with each, or the audience reach and impact each type of comic may have?

Well, y’know, The City changed over time. It’s really two altogether different strips. The City of Nineties wasn’t that political, for the first five years not at all. I had been a political cartoonist starting out, in college and then three years as a pro, and I burnt out on it. I found that genre very frustrating, and I got bored. Creating The City was liberating.

But after 9-11, editors wanted political stuff, so I changed The City to meet demand and it became very political. The weekly strips that weren’t political lost most of their papers. I probably should have re-named it. I regret not doing that. In truth, I regret continuing with it at all. I just should have dropped the mic at the end of 1999 and walked away to books. The Gen X era that gave birth to that strip was over. Alt-weekly newspapers were finished, too, although they hung on in ever diminishing form for a few more years. Problem was, the strip was still in 50 papers and making good money and it’s hard to just give that up. But looking back now, I clearly should have.

Are my books political? I don’t think Punk Rock & Trailer Parks or My Friend Dahmer are. Trashed perhaps is. Kent State is about politics, so yeah, that one.

Comics scholars often discuss drawing style as the most immediate aspect of a graphic narrative and as the reader’s entry point into the graphic storyworld. How do you feel your style works as an entranceway or an extension of the storyworld?

That’s a tough one to answer. I don’t really think about that. I draw like I draw. I’ve been at it a while. Style develops over many years, and in my case, several decades. My style morphed over time, from working the craft. I’ve always been a restless creator. I can’t hold a line for long. Some creators haven’t varied their style for thirty years. I’m amazed by that. I’ve always chased this drawing style I had in my head but struggled to get down on paper. I started finding [my style] when I started doing long-form comics – with Punk Rock & Trailer Parks – maybe because I wasn’t thinking about it too much. I took this very expressionistic style I had in my comic strip and toned it down to fit the story. It’s always about the story. How is the drawing going to service it? If you start backwards, with this crazy drawing style, you hurt the telling of the story.

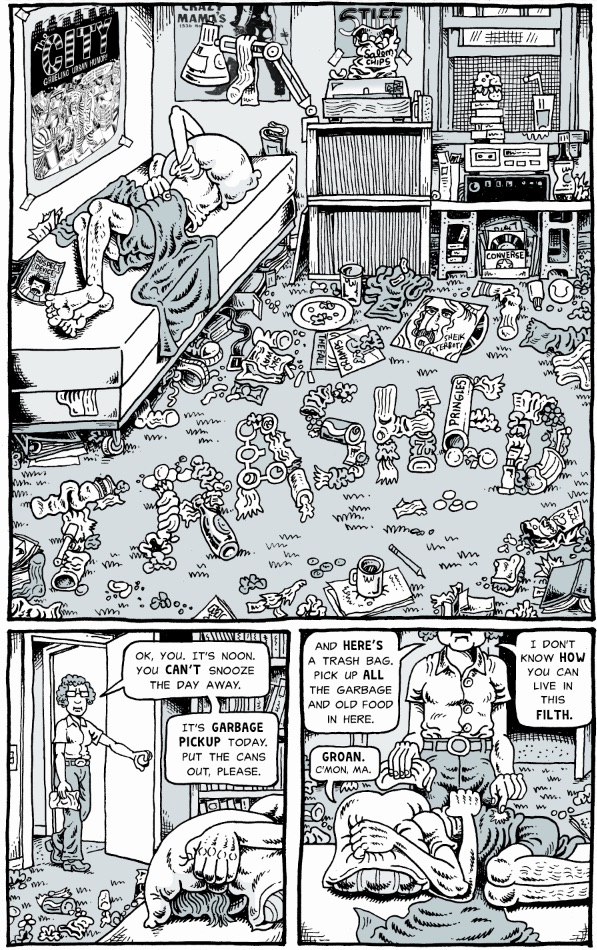

I’m particularly interested in your stylistic choice of creating panels that are overflowing with objects and background details. It seems like every time I read one of your texts, I’m searching panels to see all the paraphernalia you include in an environment. I think about how strenuous it must be to draw such a large array of objects. What are your artistic or narrative motivations for including so much visual information in your environments?

You know, that varies from scene to scene. There are scenes or panels where I pour in a lot of detail, but there are other places where I eliminate it to focus on the narrative. In Kent State specifically, when the National Guard is moving around, the backgrounds are simple, to focus on that movement. Sometimes I get carried away. I enjoy drawing, I always have. I’ll spend a day drawing tree branches. It’s very therapeutic for me. I think a lot of artists are like that. But you can be detailed without being over-indulgent. That’s where the discipline comes in.

I want to follow up on this aspect of discipline, can you elaborate on that for me?

It’s a big part of comics. You have to have it. You have to make so much work a day to meet a deadline. I learned that at a really young age, because I had those newspaper cartoon deadlines, starting in college. In addition to full time classes, a part-time job, and trying to find love – all those things that college kids try to do – I was making comics, four or five cartoons a week. So, I quickly learned how to meet those deadlines. Drawing discipline took a lot more time to develop, to learn how to shape your drawing, and not go down blind paths. Not to screw things up by over-indulging on a page, or conversely by not spending enough time on one, getting bored with it. Discipline is a lot easier than it sounds, it’s something anyone can do. If you put your mind to it, anyone can do it.

It was easier to develop discipline when I was working for newspapers, because the deadlines are so tight and so relentless, and you’ll be fired if you blow deadlines. But with a book, the deadline is four years down the road, so it’s a little different. You have to break it down to how many chapters and how many pages do I need to punch out each day.

I miss having that weekly output, even though I don’t miss doing the comic strip and have no interest in going back. I just feel less productive putting something out every 4 years instead of every week.

Despite all the visual details in your graphic narratives, there’s a thematic focus in your work regarding what is or is not seen. For example, many characters in My Friend Dahmer, don’t seem to notice Jeffery’s self-destruction. In Trashed, you visualize the otherwise unseen world of trash collection and its wastefulness by diagramming it in proportion to landmarks like the Statue of Liberty. What do you think are the comics medium’s strengths in showing otherwise overlooked issues? How do you approach visualizing such overlooked problems?

The great thing about comics, about its being a visual medium, is that you make some of these themes more interesting than they would be in any other medium. I put those visuals in Trashed because you have to see the scope of it to understand: “Holy cow this is troubling and upsetting.” For Dahmer, it was just how it was. Everything about that guy was hidden from view. It’s the power of the comics medium, and if you do it effectively, you can show those hidden things. I also like telling stories that haven’t been told. With Dahmer, there are a lot of books, but my story hadn’t been told – that first-person account from one of his friends. That was new, and unique. With Kent State, a lot of books have also been written, but surprisingly very few which bring together all the things that led to the massacre. There were a few books written just after that shootings that were very good, but that was before a lot of the information that became known years later. So, I have that advantage.

Choosing to tell Kent State the way I told it, through the eyes of the four kids who were killed, was a different concept. You see what they see, and what they experienced. I thought that would make it very personal. When they get cut down, it’s a gut punch, because you’ve gotten to know these individuals. Those are the stories I’m interested in telling.

Many of your Original Graphic Novels focus on small-town America as the site of bitter political rivalries, pettiness, consumerism, surveillance, and a lack of accountability. How does your portrayal of small-town life in texts like Dahmer, Trashed, and Kent State speak to larger national issues and identities?

Well, it certainly does. A lot of what’s driving American politics right now is small town politics – it’s amplified as you go up the food chain. There aren’t many people writing about the Rust Belt and about small towns in the Midwest, but there are a lot of great stories here. It’s also what I know, it’s where I grew up. When you have that kind of intimate relationship with a place – when you write about what you know – it makes the story richer, because you know that place, you have a relationship with that place, you know how it all fits together. What cracks me up is that a lot of readers in other countries are interested in stories from the Rust Belt. One fan in France asked me: “How was Akron, Ohio allowed to happen?” referring to the apocalyptic city I depict in Punk Rock & Trailer Parks, which was a big seller there. I’m pleasantly surprised that there’s a universal appeal to these stories.

In addition to the dead animals found in the garbage throughout Trashed (p. 47; 77; 89), you mention in Trashed's End Notes (also referred to in Dahmer's End Notes), that just a few months after the events of My Friend Dahmer, and before getting onto the truck in Trashed, that Dahmer had put pieces of his first victim in the trash. Do you think that part of the built-in obsolescence you discuss in Trashed creates a culture in which even lives are in danger of becoming obsolete and disposable?

Wow, you’re really getting deep here. I can’t say that I ever thought of that. No, because lives were disposable before built-in-obsolescence came along. That was a post-war thing, and you can’t say in WWI or WWII lives weren’t disposable. Millions are millions of lives were. So no, I don’t see the connection.

Another theme that seems to pervade many of your Original Graphic Novels is the opposition of social forces: popular forces from the bottom-up and authoritative forces from the top-down. In what ways, or to what ends, do you see these forces interacting?

Well, it varies from book to book. You have to have conflict in a story to make it interesting. Life is full of conflict, God knows, especially these days, so that’s a natural thing to include. I’m not making up those conflicts, those are what I observe. It varies in all the books.

Do you see their interaction as effecting change or to upholding the status quo?

It can be either-or, or both. In terms of Kent State, the crackdown by the National Guard occurred to enforce the status quo, but then the massacre led to systemic change. So, it’s not either-or by any means. After those systemic changes, there was a reaction that rolled back many of those changes. These things aren’t necessarily a straight line.

After the Kent State Shootings, we had the 70s, which were not a calm era, and then you had the whole Reagan thing and the rise of the Christian Right. I don’t think you can say it was a victory for progressives, by any stretch of the imagination.

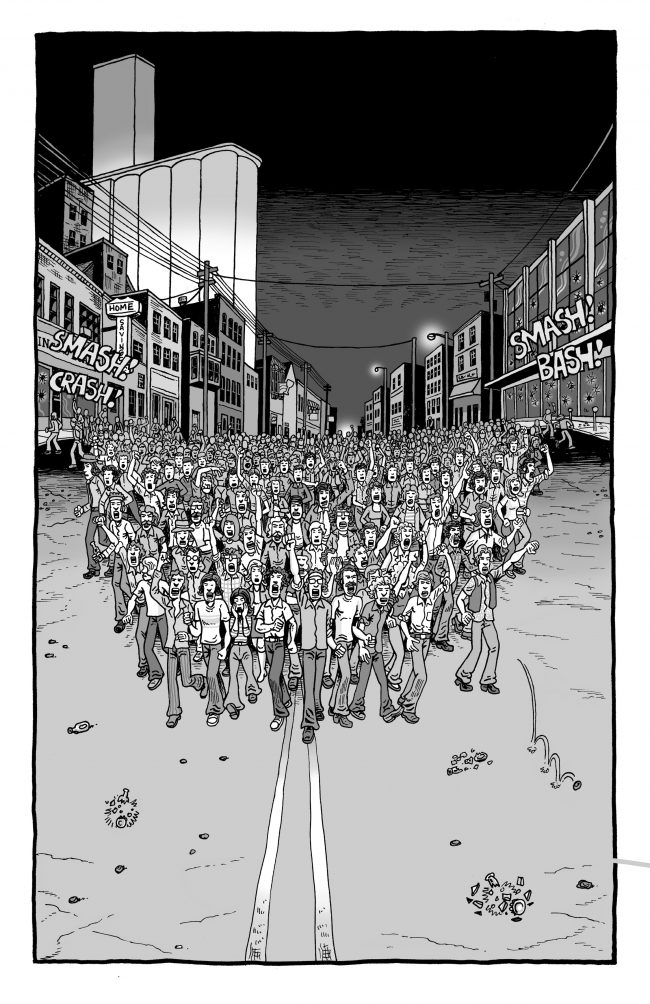

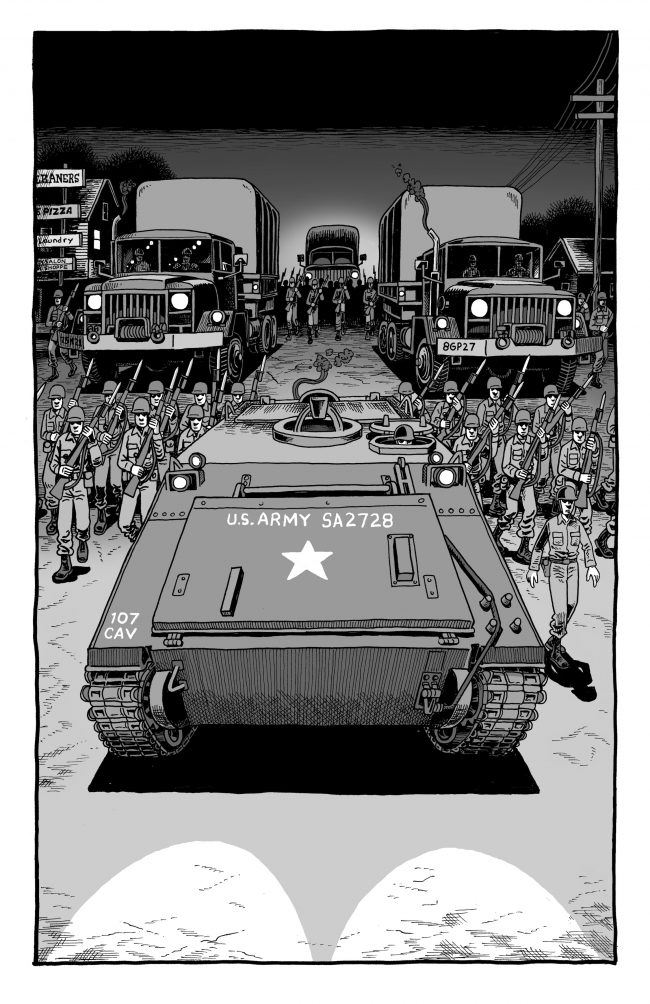

Kent State's bookend first and last images dramatically visualize opposing forces. The first image in Kent State is of a young crowd of men and women shown marching down the middle of the road, fists in the air, shouting. Through this image, the readers share the officers’ perspective of the oncoming protesters, essentially visually aligning the reader with the officers’ point of view. Why did you decide to put the reader in the officer’s perspective as their first viewpoint in the text? Similarly, why did you decide to put the reader in the viewpoint of the protesters, viewing the oncoming masked and armed officers walking amid tanks, at the end?

Well, I’m going to disappoint you, because I didn’t make that decision, it was my editor. That was his idea. But these are the images on the hardcovers when you pull off the dust jacket, so most people are not going to see them first.

Oh, that’s interesting, because I had the E-version of the text, these read as part of the main text to me. It’s interesting because some images are pulled from the text and decontextualized. Like in the text you show G-Troop swiveling to shoot from the right-hand side of the page towards the left, but that same image on the cover is backwards.

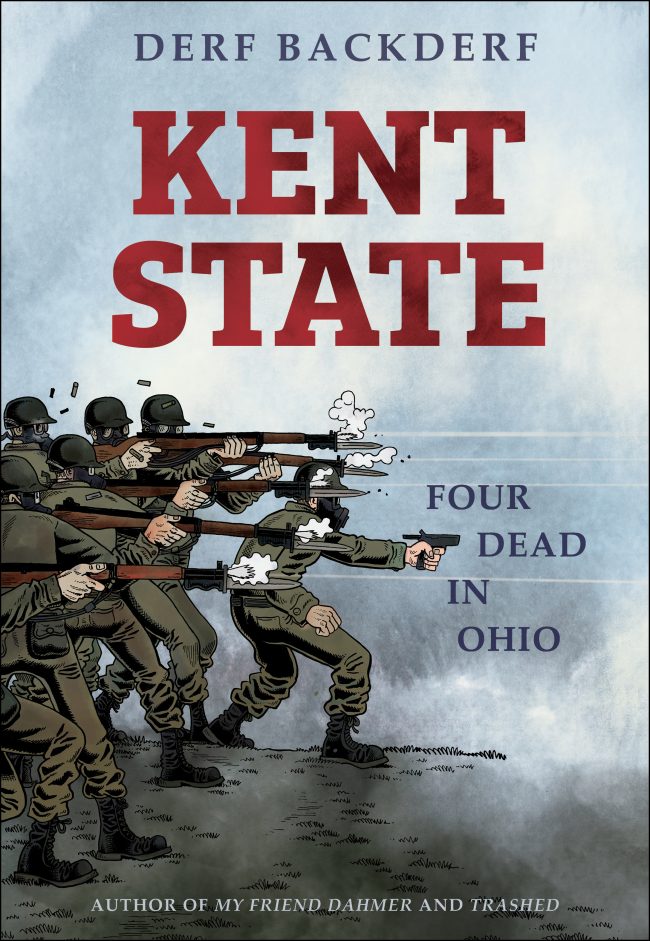

Derf Backderf, Kent State, Cover

Derf Backderf, Kent State, Cover

The action of the cover has to go left to right, toward the opening, because that’s how people read. It’s a steadfast rule in the book biz. But, that image in the text is facing in the other direction [image of the soldiers facing from right to left instead of left to right], so I had to flip the drawing for the cover.

This was really hard, because Myron Pryor, the guardsman with the pistol, was left-handed. So, after I flipped the image in Photoshop, I had to redraw him so he was holding it with the correct hand. If you notice, there’s also a disproportionate amount of soldiers on the cover shooting left-handed, because they were originally right-handers who were flipped.

The deadline was really brutal on this, and it was a massive book, so I didn’t have a lot of time to spend on the cover. It took a full month to do the cover of My Friend Dahmer. I did sixteen cover sketches before the final concept was approved. For Kent State, I knew I couldn’t come up with anything better than the drawing of the guardsmen opening fire so I told them to just use that one somehow. It’s a nice spread in the book. It’s one of the iconic moments in the story. I flipped the image and cleaned it up a bit and passed it on to the art director at Abrams, and she did the rest.

The events of the Kent State shooting, however, as you show, were not just about two opposing forces, but a number of forces violently coming together. Kent State constructs the events of May 4th, 1970, as an explosive intersection of personal, regional, national, and international circumstances. Tell me about retracing, re-creating, and clarifying the various levels of historical forces that inevitably impacted the events of the Kent State shooting. Did you attempt to show them as equal forces, or did you try to highlight one set of circumstances over another in precipitating the events of the Kent State shooting?

That’s all part of doing the research. There are a lot of sources from that time and it’s not hard to pick out the ones that matter. After many years of learning about the shootings I came to understand those forces. It’s fascinating history that I pursued on my own, long before I decided to make Kent State When I began working on the book, I studied a lot of material, and talked to a lot of people, to understand the full picture. The biggest challenge was getting a handle on the radical politics of the day. A lot of that is still pretty murky. It wasn’t reported well at the time. A lot of those radicals still have a distrust of media and writers. It’s only in the last 10 years that some of them have told their stories. That gave me names and events that I could trace backwards, and that led me to other information. It was actually a lot of fun, a bit of detective work, particularly researching the Weathermen, who were the radical fringe of the student antiwar movement. They became full-blown terrorists. I went down a rabbit hole with them, because it was so fascinating.

Before moving on to a deeper discussion of the various perspectives encompassed within Kent State, I’d like to ask you about developing characterizations.

The City strips rely quite a bit on caricature creation unlike your longer form works, which focuses more on characterization. Tell me about the differences in consideration between these two forms. What sorts of considerations go into caricaturing individuals rather than characterizing them?

That’s the difference between satire and storytelling. A caricature is there to make a point, either humorous or political or both. A character, say Otto in Punk Rock & Trailer Parks, is a fully realized individual, with a back story and a personality, and flaws and strengths and quirks and all the stuff that makes a person. A caricature is there to service the gag. A character is something you build an entire story around.

The weekly strips of the Nineties were so amazing, and distinctive, and it was a daunting challenge to make it in that field, competing for space with Lynda Barry, Chris Ware, Alison Bechdel, Ben Katchor and all the rest. Cumulatively, I think the weekly strips were the best comics being made at the time, bar none. It’s a genre that hasn’t been given its historical due.

I have trouble looking back at my old work now, and The City was definitely “of its era,” but I was in a lot of papers and it was great fun… until the newspaper industry went down the shitter. Luckily, I was already focusing on books when it did.

Kent State involves the almost random nexus of a number of people and perspectives violently coming together at a moment in time and space. As a storyteller, can you tell us about the difficulties or considerations you took in crafting the first act of Kent State where Bill, Sandy, Jeff, and Alison’s lives are first introduced to the reader? How did you work to organically unfold their stories in the days leading up to May 4th, 1970?

The first challenge was finding out what these four people were like. I thought the best way to do that was to talk to the people who knew them. So, I zeroed in on their friends and roommates, and accounts by their family or contemporaries. We’re talking fifty years ago, some of these people are gone, their parents are all gone, and memories fade. But I was really lucky to find some people who were willing to talk, who had very clear, very detailed memories, and that’s where I started. It’s a dramatization, of course, in the sense I’m creating conversations, but hopefully, it’s true to the spirit of who they were. And, I tried to focus beyond the events of May 4th, on their pastimes and hobbies, their lives on campus, their hopes and anxieties. When you put it all together, it is like character building in a way, but you want it to be tethered to reality, you don’t just want to make shit up.

I also spent a lot of time on their visual portrayal. For some, their looks were very distinctive – like Jeff with his crazy hair – but others weren’t as easy. The important thing is that the reader can immediately recognize the various people in each scene. I’ve never done a story with this many characters, so that was a big challenge.

At the end of My Friend Dahmer, you characterize your 18-year-old self as having already begun his adult life (p. 186), yet throughout Kent State you most often refer to the Kent State students as kids, even though they are adults between the ages of 18 and 22. What is your reasoning behind this rhetorical choice (p. 18-22; 33; 260)?

You know, I hadn’t really thought about that. I do indeed say that at the end of My Friend Dahmer. But when I was in college, people often called us “college kids,” so that’s how I thought of it [for Kent State]. And in 1970, they weren’t legally adults – because 21 was the legal age at that time, not 18. You could be drafted, but you couldn’t vote. But they were so young. Alison wasn’t even a year out of high school when she was killed. By 1978, when My Friend Dahmer ends, the legal age had been lowered to 18. So, it’s not incorrect.

One of the techniques I used to write this book is, my kids are in college right now, and are roughly the same age as the four. For some of the emotional scenes at the end, I imagined them in the scene, and thought about what my emotions would be if it was them. I was trying to really conjure up that kind of horror and shock that the people who knew them felt. What would you do if you saw them dead on the ground – that famous Neil Young lyric [Neil Young, “Ohio,” June 1970: “What if you knew her / And found her dead on the ground”].

When I was 18, my head was so far up my ass, I couldn’t see daylight, but here were these kids throwing themselves in front of the combined might of the US government, facing down these cops and FBI agents and 1,200 soldiers, and doing it fearlessly. And today, those BLM protestors, many of them are still in high school– it’s the same displays of courage. I marvel at that.

In this text, Kent State University also functions as a dynamic character. Kent State is depicted as an educational institution bettering future generations; a generator of liberal thinking and debate; a cultural hub; and a center for political activism. But you also show how Kent State was tied to military training and activity, and how it also became a political threat, which in turn made it the target of violent aggression. This is not exclusive to Kent State, of course, but has been indicative of a number of post-secondary institutions throughout history. Tell me about your process of depicting Kent State not just as a place but as a character within the text.

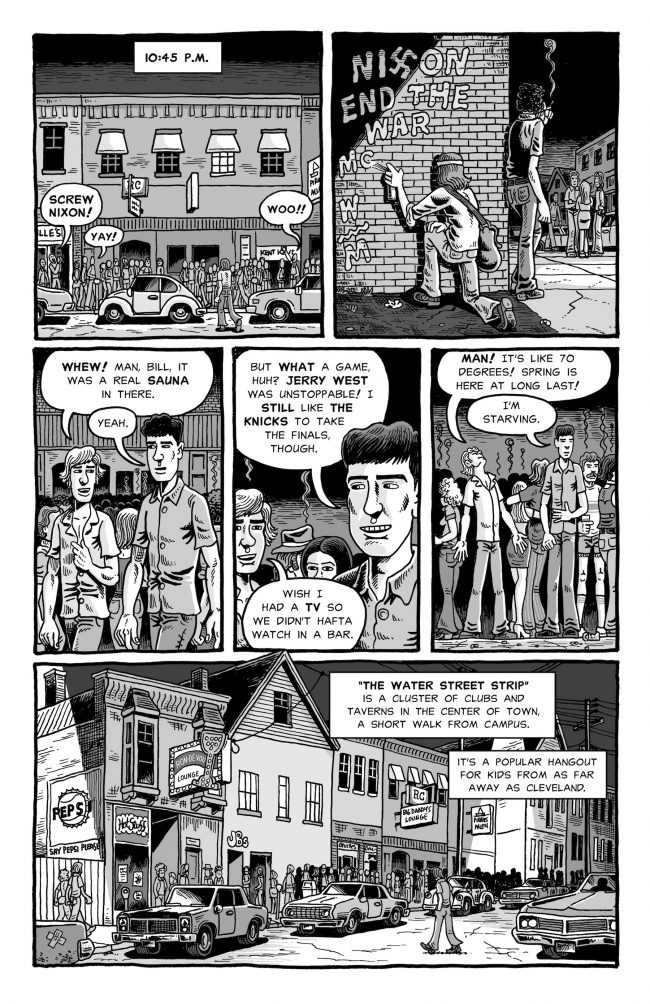

It helped that I knew the KSU campus and the town. I grew up nearby. I used to hang out at the music clubs on Water Street when I was a garbage man – so all my books tie together on some level [chuckle]. I was familiar with the vibe of the place, as you can only be when you have spent time there. But, I didn’t go to KSU. I went to Ohio State. OSU was very similar to KSU in 1970. Actually, the protests at OSU were worse. Ohio State was much bigger, with 45,000 students, and had much more aggressive protests. The massacre didn’t happen at Ohio State, it happened at KSU. It could have, maybe should have, happened at Ohio State.

KSU was a special place in 1970. The people that went to KSU, and were scarred by those events, still have a real fondness for the school. There’s such a connection we all have to our universities. It’s where you find yourself, where you’re on your own for the first time. You never forget that place and what it meant to you.

The problem was, KSU has been transformed over fifty years. There are still common characteristics, but the campus and the city has changed a lot. Purely as a visual document of this place, it was really a challenge to zero in on this one weekend in May 1970 and get the visuals factually correct. That took many, many, months of research. It was a visual minefield. But it was very much like a character for me, like building a visual representation of Jeff or Bill, I was building KSU. It’s the same process.

I do that with all my books. I make the setting a character. I just think that way, of a setting as character. Place has always been very important to me.

Coming back to viewpoints, your personal viewpoint at the time of the Kent State protests, and later shooting, was as a ten-year-old child peripheral to the action. Now, fifty years later, 10-year-olds have been watching similar events unfold through the George Floyd protests and their government’s extreme response to its own citizens. How do you think viewing such events at an impressionable age impacts future generations? What impact did your peripheral witnesses of the Kent State events have on you?

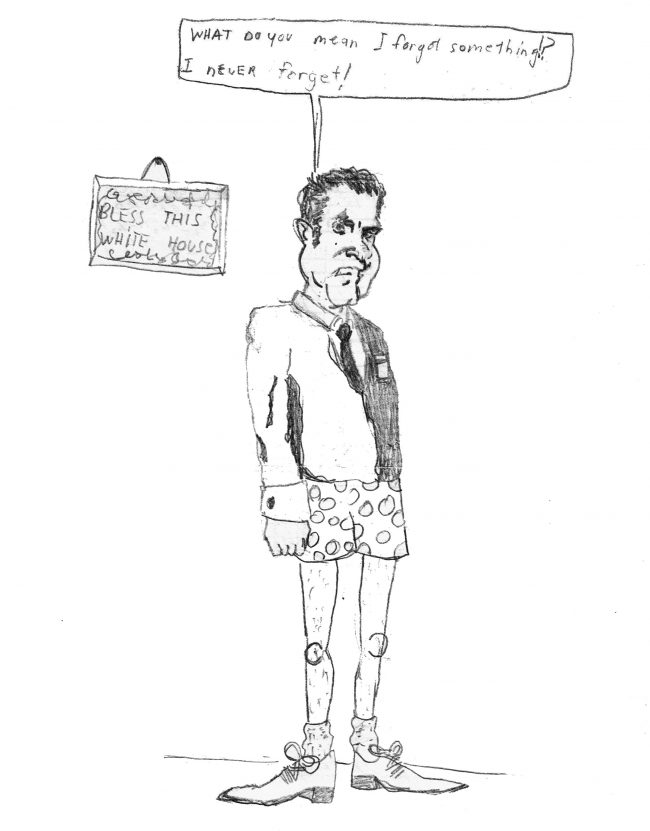

It had a very profound impact, because of my personal connection to it, the guard was in my hometown before it rushed off to KSU. When I realized it was the same guardsmen that opened fire, it really left a mark on me. I was actually drawing political cartoons at the time – I was drawing Nixon, in 1968 – it’s drawn on the back of one of my dad’s golf league sheets! I drew on anything that was on hand.

This one is spooky. This is a cartoon of a little toy guardsmen marching off to war, on the back of an envelope. It’s marked 1970, by my mother, who saved much of my artwork. So that’s the impact of the Kent State Shootings right there on me. And, as you know, I started out as a political cartoonist, so that’s where the seeds of that were planted, at age 10. I realize that sounds obnoxiously precocious, but here is the proof.

Looking at these old cartoons again, it’s the same feeling I had after Jeff [Dahmer] was arrested and I pulled out all the drawings I did of him in high school.

The lesson there, kids, is save all your own work, because you never know when this stuff will come in handy [chuckle].

It’s interesting how personal history meets with larger moments of history.

Great moments in history fan out through society and affect people in different ways. I try to get that across in the book, without pretending to play an integral part in the story, which I didn’t. In fact, I didn’t go to KSU because of the shooting. I was 19, getting off the garbage truck, and picking a college. I liked the area and a lot of the things about KSU. But there were still big protests on campus in the late 1970s, with the university wanting to build on the shooting site. They had to drag hundreds of protesters away, including the parents of some of the murdered kids. I just didn’t want to deal with all that, and scratched KSU of my list, so the shootings continued to affect decisions in my life.

Perhaps it’s damning to admit this, but your texts are often my first encounter with the subject-matter you present. I did not know of the circumstances at Kent State fifty years ago. For some readers, your work will perhaps be their first encounter with these events. What potential impact do you think your re-construction of these narratives and your interpretation of the information will have on these events’ future understanding?

It depends. I think it varies from generation to generation. I think the Kent State Shootings for people older than me, they know exactly what happened. People my age and maybe into Gen X sort of know what happened, but not the details. For people younger than Gen X, maybe they haven’t heard of it at all, or perhaps only know it by name. There will be varying degrees of knowledge. I think, no matter how you come to it, the reading experience will be emotional, because that’s the incredible power of this story. And maybe, some people really don’t know that the four protagonists die, even though it’s right there on the cover. I was worried about that, but the editors felt enough people knew what happened at Kent State that it was okay to put [Four Dead in Ohio] on the cover. Then, you have foreign readers, who don’t know the story at all and will get a different reading experience altogether, which is okay.

On a similar note, historically based texts are somewhat of a balancing act between subjective interpretation and objective information. Your own surmises about the information are inevitably tied to this narrative as we’ve discussed, but eyewitnesses also have a personal stake, so do university administrators, as well as the members of the national guard. When choosing to tell a historically based story, and one of such a traumatic event as this, how do you balance subjective and objective information?

It’s a decision any author has to make. All books are subjective to a certain degree. That’s also why there’s so many footnotes at the back of the book. I document everything, including the things I struggled with, and the opinions of those on the other side. I list my source material for every scene, so you can go to the source material and make what you want of it. The footnotes of Kent State are much more comprehensive [than Dahmer], and I felt it was important to have those. Some people will squawk about my conclusions, and there’s still fighting over what happened, especially in Ohio. As we know, we live in a post-factual world, so there will always be screaming about controversial events.

That’s one of the reasons I included the account of a guardsman, who was one of the shooters, and it was important to have it. He’s not really a sympathetic character, in fact he’s an unrepentant hard ass. But that’s why it’s so important to have that account there, because I needed a counter to the student protesters, to understand what the soldiers were experiencing and thinking. It’s multifaceted, there were a lot of people and opinions, and it all ended in tragedy.

This line of questioning leads us to a well-tread issue within discussions of memoir and historically based works, which is that of reliability. Tell me about the issues of reliability you ran into when constructing Kent State. How do you, or do you, chose to signal the ambiguities that arise when taking on such a project?

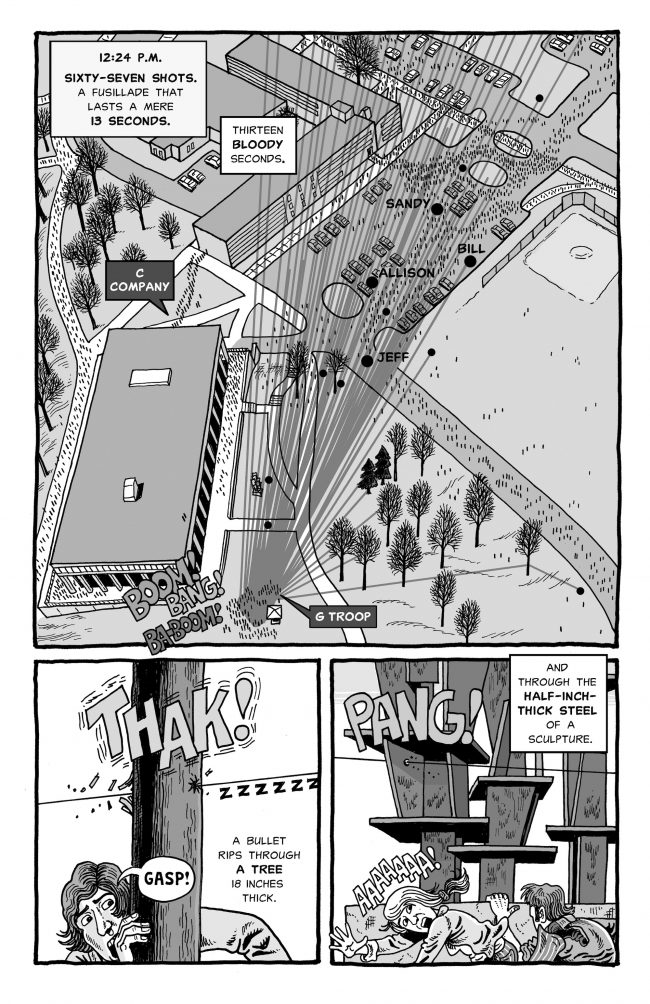

There are some tricky parts – because we still don’t know why a couple big events in the story happened – because there was a coverup and people lied and they’re still lying. We don’t know, we suspect, but we still don’t know, because no one has fessed up to it, why the Guardsmen fired. The shooting itself was the hardest scene to write. I think I pulled it off better than a lot of other books have, because of the visuals.

As far as memoir goes, memory is tricky thing, and I never rely on it solely. If you notice in the footnotes, many of the scenes have multiple sources and corroborating evidence. I’m looking for at least three corroborating sources. That’s how I was trained in journalism school. I’m not just looking at memories or personal accounts. I’m [also] using newspapers stories and FBI reports, then I compare and contrast. And yeah, some of the people I interviewed, their memories were off. Other people carry a lot of baggage, they’re not going to believe this or that, even if it’s documented or reported. You have to take all that into account.

Some people told me that they liked the footnotes in My Friend Dahmer better than the book, which really pisses me off [laughs]. Then you get the inevitable question, “Why didn’t you write it as a proper book?” meaning, of course, that comics aren’t worthy to tell such a story. But a lot of the research and the detail are not in the text and dialogue because it is a visual medium. I spent a lot of time getting the visuals right. Like the Water Street bars. I spent months getting those buildings correct and what was there in May 1970. A lot of readers may look at it and not know there was so much research in a particular scene. It was tricky. At KSU the difference between campus in 1970 and, say, just five years earlier or later is significant, so I had to be very careful. I had that [same level of visual research and detail] with My Friend Dahmer and Punk Rock & Trailer Parks, because they were period pieces, too.

Your historical narratives don’t tend to be strictly chronological. Although the events generally progress over a linear time period, your narrative sometimes jumps between historical backstory leading up to the events, or meta-narrative commentary signaling what we have come to know since the events. How do you think about or work on including extra-diegetic information? How do you approach structuring background information or information discovered after-the-fact into the story while still ensuring narrative cohesion?

That’s a tricky balancing act, because there’s so much backstory here and it’s important. The shootings were the culmination of a decade of unfolding events and political movements. I didn’t want to get bogged down in backstory, because I wanted it to be crisp and intense. I didn’t want to lose the tension. I tried to sprinkle backstory throughout the narrative, so the story wouldn’t get bogged down. Since I narrowed the story down to the May 4th weekend only, just four days total, it was a challenge to work in that backstory. This is where the footnotes come into play, where you get much more information on a scene, if you care to read it. So, it was a bit of juggling act, honestly. Especially when you’re talking about radical politics, it’s so complicated. [Radical groups are] constantly forming, breaking apart, and feuding with each other. It was hard to understand what happened, and then to depict it clearly.

A related issue to, or perhaps an antidote for, reliability in these types of narratives is the presentation of documentary information to the reader, so I’d like to talk about some of your inclusions throughout Kent State – primarily the use of maps and photographs.

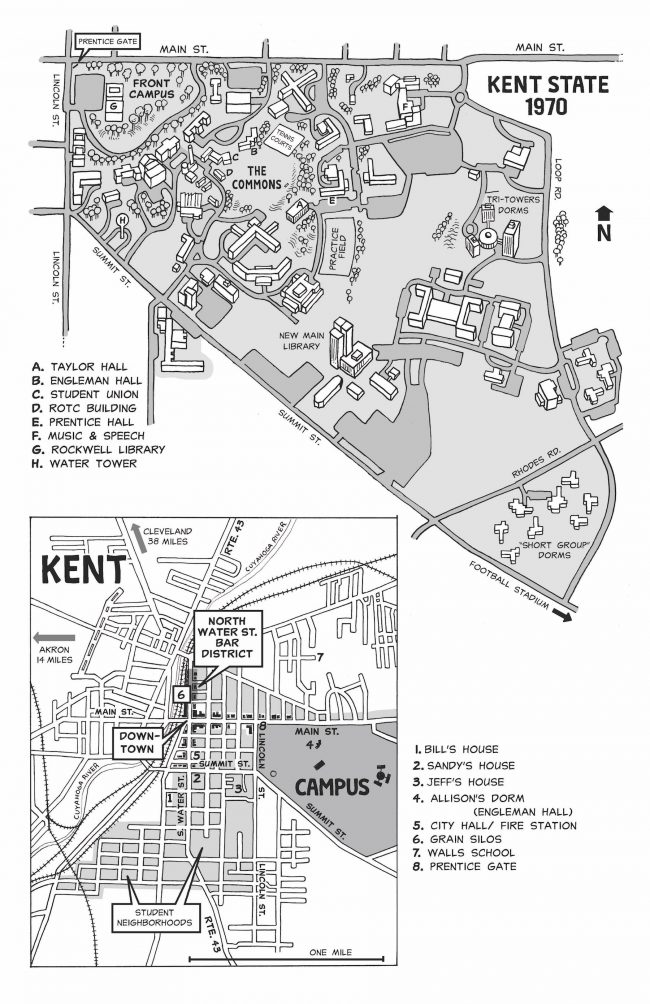

You begin Kent State with two maps: one of the campus and one of downtown Kent, which indicates the residential locations of the students who were fatally shot during the events of Kent State. Maps have interesting associations both with histories and particularly with historical events depicted in comics form. Tell me about your choice to use this type of document at the outset of the text.

I come from a newspaper background. I spent a lot of years making maps as part of my various jobs in newspapers, going all the way back to my college paper. The only way many newspapers could justify hiring me as a cartoonist was that I could also do things like maps, which were considered essential. There’s a reason that newspapers used so many locator maps, until they laid off all their artists. For example, in a crime story, a map can clearly show where everything happened.

This gets back to your earlier point about Kent State University as a character – here in this map is what the character looks like. I don’t know if people will refer back to the map while reading, but that’s the hope and the reason I included it. It’s like Tolkien’s map of Middle-earth at the beginning of Lord of the Rings. Readers constantly flip back to that as they read.

Making a map was also part of my research. Recreating the campus and the town of 1970, I needed the map as reference for me, and then ended up including it in the book.

The other challenge with the campus is that it exploded in size from 1960 to 1970. In 1960, it had 6,000 students and just 29 buildings, by 1970 it was 21,000 students and over 100 buildings. I’m not aware of any other university that grew that fast. Rolling Stone magazine called Kent State “The country’s largest unknown university” (see Kent State page 17). It was this big school and nobody outside Ohio knew where it was.

I did the same thing with My Friend Dahmer. I had a schematic drawing of the school where most of the story takes place [Revere High School, Ohio]. I knew exactly what it looked like at that period of time. So, I could move people in space and know what I needed to draw in the background of any given scene.

The fact that KSU is in flux is a theme in the book. Of course, the aftermath of the shootings is that then the university stopped in its tracks. May 4 ended that dream of becoming a major university. KSU would have no doubt grown to a school of 35,000 students in a matter of years, if not for the massacre. It’s only now that it’s starting to recover. Fifty years later, it’s still dealing with its past. There’s an aura of sadness at Kent State that you don’t really find elsewhere. You can feel it when you visit. Maybe it’s the old students that still live in town, or the vibe of the place, but you feel a palpable sadness. You can go to that sculpture on Blanket Hill and put your finger in the bullet hole. You can go to the parking lot and see the memorials to the four students, on the spots that they fell. It’s still incredibly moving to walk through those spaces.

As for the use of photographs, the opening of My Friend Dahmer includes William S. Henry’s photo of Jeffery Dahmer at Revere High School in Ohia, circa 1978 (p. 8). This photo is ambiguous as a documentary object and does not reveal any kind of “truth” about Dahmer as a person. I’m curious as to your thought process behind including a copy of this photograph in DAHMER and your choice not to include any copies of photographs of the four shooting victims – Bill, Jeff, Allison, and Sandy – or any of the other key players of this historical moment in Kent State.

Well it does [reveal a truth about Dahmer] because he’s doing his schtick – his crazy cerebral palsy imitation. There’s something else in there, too. He’s holding a Styrofoam cup in his hand, and that’s what he used for his booze when he’d walk around school. Scotch, or whatever. He would carry it around the hallways of school, right past vice-principals, teachers etc. It shows how clever he was, going to the cafeteria getting a cup of coffee, throwing out the coffee and putting booze in it. So, it looked perfectly normal, just another kid with a cup of coffee. And Jeff had this incredible ability to mask emotion. Other students would have been sweating bullets, but Jeff was never caught, he walked around with hard liquor every day, and never got caught.

There are amazing photos from May 4, iconic photos, some of the most famous photos of the 20th century. Mostly taken by students, which pleases me, because I was a photojournalist in college, too. Because those images are so well known, I didn’t feel like I wanted to go there. The choice of not using [photographic] images of the four, well, I was trying to establish their visual identities through the drawings alone.

There aren’t a lot of photos of the four. We had a different relationship with photography back then, just based on the technology alone. You couldn’t just take out your cell phone and start shooting. Back then, you had to have a full rig: you had to have an expensive camera, multiple lens, a flash, and various speeds of film, then you had to get them printed, or print them yourself, for which you needed a full dark room. Photography required a great deal of knowledge and skill. You needed to know how light worked, and how to shoot in daylight or at night. There was a huge learning curve, and it took talent. It was expensive. So, there aren’t the number of candid photos you have now, where people can just take out their camera phones and fire off 50 shots and the computer in your phone does all the work.

At times, in Kent State, you redraw photographic images, such as John Filo’s photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio, over the body of Jeff Miller (p. 236; see also back cover); however, you do not call attention to the documents as redrawn photographs like other cartoonists do – for example Art Spiegelman in Maus and Alison Bechdel in Fun Home. Instead, you seem to use the photographs as diegetic panels, altering their angle of viewing, or eliminating background objects and individuals from them. Can you tell me about your thought process behind depicting photographic evidence either in its original or altered form in comics journalism?

I think it’s okay if it’s true to the facts of the scene. I used photos as photo reference only, to draw a moment in time. I didn’t trace them. In the case of John’s photo – which is one of the most iconic of the 20th century – what I tried to do was not focus on the figure of Mary Ann Vecchio, but rather, on her scream, which carries over three pages. It starts on the page before and then it rises up over her to the guardsmen on the next page. In the photo, we don’t have that sound effect, obviously.

And the same thing with the guard turning and opening fire (pages 218-219), I replicate the sound effect in the tape recording of the shooting. This is one of the things that comics can bring to the telling of this tale.

What you also get from the lone video footage of the shootings is you see how far away the students from the guardsmen. When you’re there on the site, and you stand in the parking lot and look up the hill, it’s an incredible distance away. Most people haven’t gone there and put themselves in the space, and never will, so that’s another thing comics can do, visually, is show that space and that distance. It’s a key point. The Guard insisted they fired because they thought they were about to be overrun. It was a lie. I show that it was.

It’s unbelievable when you see that video footage, how far away the protesters and passersby were down the hill. It’s unbelievable that so much damage happened in thirteen seconds.

It could have been worse, much worse. A month later, the guard got M16s, the standard combat gun used by troops in Vietnam. The National Guard had old M1s from WW2, antiquated single-shot rifles with clips of just eight bullets. You had to repeatedly pull the trigger to empty the clip. M16s are assault rifles and have a clip of 30 rounds. You just hold down the trigger and the gun keeps firing. Can you imagine a spray of 30 bullets from a dozen assault rifles tearing through that crowd? Dozens would have died.

This discussion leads me to thinking about the roles that surveillance and media played with regards to the events of Kent State, and also how you depict these issues in the book.

Surveillance seems to be another shared theme between Trashed and Kent State. While it occurs in a top-down fashion in each – with those in positions of authority using surveillance upon those in positions of limited authority – in the aftermath of the Kent State shooting, it also seems to exist in a bottom-up way with students taking pictures, videos, and recordings of the increasingly aggressive occupation of Kent State University. What kind of impact, or what kind of culture, do you feel these mutual acts of surveillance are creating within the book and within larger society?

Well we’re seeing it play out in the protests that we’re having right now aren’t we? Technology is really working in the favor of activists today. It all started obviously with George Floyd being killed. We see it all unfold on video, and it exploded all over the world. They didn’t have that technology in 1970. One of the reasons the Kent State cover up succeeded is there wasn’t clear video footage of the Guard shooting. It only lasted 13 seconds. There’s only one film, taken from very far away.

Once the shooting started most of the student photographers wisely hit the dirt. In fact, one of the students that was shot [John Cleary] was trying to take a photo at the time of the shooting, because unlike today, he couldn’t just lay down and put his hand up with his phone to capture it (see Kent State, page 227).

A major theme in Kent State, one of those hidden things we talked about earlier, is the vast secret war that Nixon was waging against the Antiwar Movement. It involved every federal intelligence agency, the FBI, CIA, Military Intelligence. The methods they used were both illegal and unconstitutional. These spooks were on every campus in the country in 1970. They were at Kent State, in force. The paranoia of Nixon was behind this, and his paranoia infected much of the country at the time, or perhaps he rose to power because of the paranoia of the country. We’re seeing that happening again.

How do you think today’s digital and information age is changing the nature of protesting and its documentary history, as opposed to what was available in the 1970s? What if the events of Kent State had happened today, how do you think both the events and their future understanding would have been different?

I’m not sure. I think, “Would the shooters have been punished?” I don’t have a lot of optimism there. Here in Cleveland, there was a 12-year-old kid that was gunned down by cops, for playing with a toy gun in the park, and neither of the two officers were indicted or prosecuted [Note: Tamir Rice. Nov. 22, 2014]. An unfortunate aspect of American life is that police get away with everything, and always have. With the Kent State Shootings, if we had today’s technology, there would be more evidence out there, but you’d still have the media and the politicians spinning things every which way. We no longer have a press that functions as a fair documenter of events. There’s no pretense of that at all. I don’t think it would have played out a lot different, honestly. I wish it I could say it would.

My position was, before the BLM protests started, that I wanted this book to be a warning for the way things could go if we kept barreling along this path. I’ve actually been criticized online, by people who think I’m shamelessly capitalizing on what’s happening with the BLM protests. Like I made a 280-page book in a week! My premise, when I handed in this book in September [2019], is that all the same forces that were in play fifty years ago– an authoritarian president, hyper-partisan politics, police aggression, and massive paranoia and misinformation– are back. We’ve circled completely around to 1970, and apparently learned nothing along the way.

Kent State was always meant to be this cautionary tale. Learn this history, because we don’t want this to happen again. We seem to just be steamrolling toward tragedy. Everyday, I wake up terrified I’m going to read that some cop has gun-downed 15 people.

Do you feel that the saturation of images in the digital age is creating a type of informational obsolesce, where we are so inundated with volumes of information, we stop paying attention to it? How do visual narratives like Kent State contribute to or disrupt this potential ‘banality of images’? (See Hirsch, 2001, 216; Sontag, 1977).

I don’t know if there is a banality of images, some of the images that have come out of the recent protests have had a big impact. A photo from the first riots in DC, with the protester walking in front of that flaming building with the American flag carried upside down. I think it was an AP photographer [Note: Julio Cortez; Thursday, May 28, 2020; Minneapolis, MN]. And of course, the protesters that were gassed in Lafayette Square [Note: Monday, June 1, 2020; Washington, DC], so Trump could wave around a Bible – those images may be his downfall.

The genre of comics itself is still a bit unusual for recounting a story like this, at least to the public at large, not to us enlightened comics folk. There have been a lot of books about the Kent State Shootings, but no one has done a graphic novel. It’s a unique take and unique depiction on those events, which hopefully will make it stand out. I’ve gotten some pushback. One of the photographers who took some of the May 4 photos said there was no way comics could legitimately add anything to the historical account of the Shootings. We had words over that one. It’s the stubborn backward attitude about comics as an artform. Like this was Archie & Jughead vs. the National Guard or something.

In the Kent State's End Notes, you describe the initial media apathy regarding the protests at Kent State, then the media sensationalism following the Kent State shooting – which also reflects current media coverage of national politics and the protests of May 2020. You later point to the problematic corrections and retractions to the initial reports in the aftermath of the Kent State events. What do you feel the media’s role should be in disseminating information about important news and events to the public, and how does slow-form comics journalism fit into the realm of media reportage?

I have the benefit of hindsight, which the journalists covering the events of May 4, 1970, did not. I knew a lot of the folks who covered the Kent State Shootings, I met them later in life when I worked in newspapers. Breaking news is so difficult to cover. How often are the media dead wrong from the beginning, and then they have to course correct over days? That’s just the nature of breaking news. It’s often chaos. Especially with something the government wants to cover up, because they are releasing so much misinformation. It’s not fair to compare my book to breaking news stories, because I have years of documentation and information and clarity they didn’t have. And if you look back on the Shootings, they did get a lot of it right. There are some of the old radicals who thought the coverage was absolute shit, and still do, but they have their own personal agendas. I understand their criticisms, but I don’t agree.

Now some indeed got it completely wrong. The local paper in Kent had a banner front-page headline that read “2 Guardsmen, 1 student dead” [The Record-Courier; May 4, 1970]. It hit the streets just a few hours after the shootings. The locals saw that headline, grabbed their shotguns and rushed out to look for students. That unforgivable error actually put people in danger.

But the Akron Beacon Journal, which was a bigger and much better newspaper, won a Pulitzer for its coverage. The KSU student newspaper [Daily Kent Stater] was also great with coverage of events leading up to May 4. No one covers a campus better than a campus newspaper. Unfortunately, they were closed down when the university closed down, which was a shame, because they would have had really good coverage of the shooting (See Kent State page 256, Note Page 16).

It’s interesting how all these levels of papers – campus, local, regional, even national – create an interconnected web of information.

You quickly learn what sources to trust and not trust, it just comes from carefully reading the material. If you see too many errors or slanted coverage, you just say screw them, and focus on the ones that got it right. I didn’t use the Kent Record-Courier much. It was a rotten paper and its coverage was very slanted. The paper infamously ran a large house ad a few days after the massacre, thanking the National Guard! The Akron Beacon Journal, on the other hand, was a primary source, because it was the finest paper in Ohio at the time.

The underground press was a good source, because it covered the protest movement from the ground. The mainstream press had difficulty getting access to radical groups.

Is the media accountable for its misinformation? What about social media?

Sure. Social media is a whole different animal, which had no bearing on what happened at Kent State in 1970, obviously.

In this same vein, I found your Epilogue to be incredibly impactful. Can you tell me about why you chose this as the end scene of Kent State?

As soon as I heard it, I knew that was going to be the epilogue. That was a year before [the book was finished]. Every year, there is a May 4th Commemoration on the KSU campus. This was supposed to be the 50th, which was wiped out because of the [Covid-19] pandemic. I felt so bad for the students of 1970, because this was going to be their moment. The university was finally supporting it, after decades of opposition. It was going to be a huge event with all these old protesters and students returning to campus. They might not get another chance, because these folks are all in their 70s now. Many are in failing health.

I've been to quite a few of these over the years, and they’re always very moving. The keynote speaker in 2019 was Bob Woodward, who revealed the contents of this Nixon tape. As soon as he read the transcript, I knew that was going to be the epilogue to Kent State. I had never heard it before, no one had, but what Nixon and Haldeman said on the tape summed it all up, and fuck those guys. It’s easy to see Trump saying something like this, too. But yeah, it’s chilling, but that’s the way they were thinking in 1970. “Shoot ‘em all.” That was the popular opinion.

After Dahmer, Trashed, and now Kent State, what social or historical commentary would you most be interested in covering or investigating? Conversely, what commentary or events would you never want to take on, even if you’ve thought about them a lot? Why?

I don’t know the first part; I’ll be coming up with my next project this summer, since I now have lots of unexpected free time. I tend to mix it up and hop between comedy and serious stories. I’ve been kicking around a couple ideas.

Topics I wouldn’t handle… I don’t want to get into cultural appropriation. You have to think – what topics do I have a right to tell? You have to consider that, and that’s very valid. That would be the only thing holding me back. I also don’t want to do anything similar to what I’ve done before. People often ask when I’m going to do the rest of Dahmer’s story. Never. It’s not my story, and it’s gross. With my next book, I could do something contemporary, or something in a different period of history.

Kent State (Abrams Comicarts) by Derf Backderf is available on September 4, 2020. See your local retailers.