Interviewer: Would you consider Napkin a pornographic work?

Carta Monir: I would, although not in the same way as like… straightforwardly titillating porn, you know? It’s not the same as a porno video you watch online. It’s an extension of my personal practice, this impulse that I have to share my thoughts and experiences as candidly as possible. When I was working on Napkin I knew that I wanted it to be explicit, because I’m talking about explicit experiences. There are parts I specifically intended to be pornographic, like the short story about the grindr hookup, but other parts feel more functional, I don’t know.

It would feel rather redundant to say that the sexual experiences that Carta Monir explores in her personal photocomic zine, Napkin, is a shining example of 2000s-style third-wave feminism. Napkin, published in March of this year, explicitly explores the author Carta Monir’s experiences with sex, sexuality, polyamorous relationships, and gender with the power of the author’s knowledge of modern intersection feminist terminology as well as the power to tell her own story, by her own terms, in a way that just wouldn’t have been possible in the era of first-wave feminism of the early 1900s, which focused on women’s right to vote & work, or even the second wave of feminism, which heavily focused on the personal being political. As such, once the world realizes that the personal is political, it also must acknowledge the very messy complexity of being a person is not only in what your job is but also in who you choose to be as a person. In Napkin, Carta Monir chooses herself, chooses to have a bunch of awesome sex, and chooses to tell her readers all about it in a thoroughly personal way. She declares that her body is quite literally her choice and that she may do with it as she pleases, while also giving Napkin a very definitive pathos that makes it not only an explicit work in a sexual sense but in an emotive sense as well.

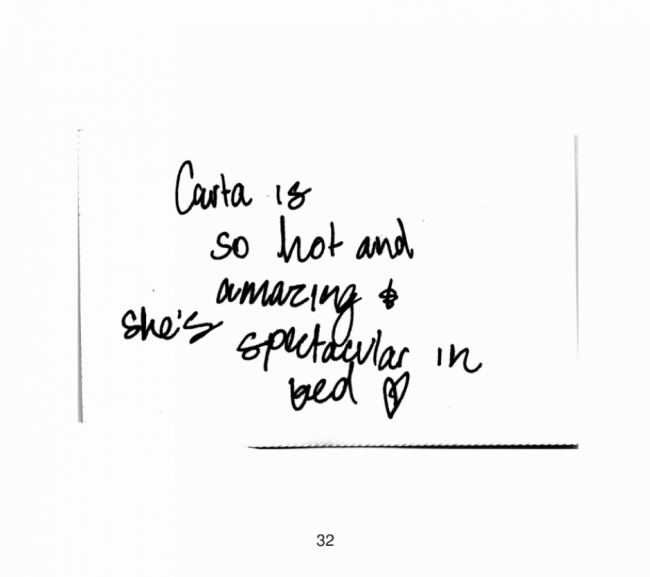

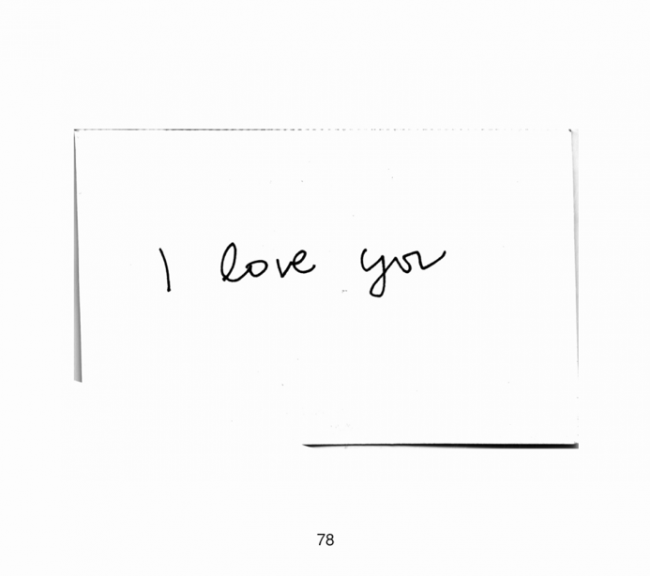

Napkin, despite its nature as a personal zine with retro trappings, is still a thoroughly modern work from the identity of its author to the literal paper it was crafted on. While the utilization of varied technology to tell a story is nothing new (left-leaning political movements have always used technology to some degree), the way in which Monir brings Napkin to life specifically connotes the more nostalgic efforts of the 1980s, with its use of scanned pictures, handwritten notes, and Polaroid pictures, while using modern language and slang throughout its prose to ground Napkin back into the present. The quality of the risograph work gives the reader the impression of something vintage and messy while still intimate and necessary. The lack of polish that Napkin employs throughout the work leaves the reader with the impression of a friend sharing stories about their sex lives -- the reader is given an in on Monir’s emotional state, which bleeds into the very conceit of Napkin itself -- that Carta Monir wants to tell you some stuff about her sex life and her feelings about her sex life. As such, Carta’s work being a third-wave feminist work (in this case) means that Carta is centered in her gender and sexuality in a healthy way, leveling the playing field by using the medium of risograph printing to get her story across without the need to answer to too many white, cisgender feminists gatekeepers in the more traditional publishing world. By seizing the means of production to tell her own narrative, Monir exemplifies that she can and will discuss topics such as sex, gender and sexuality without the need to dehumanize herself to get her point across; sexy without being a sex object, important without being pedestaled. In Napkin, Carta Monir is a person who happens to like having sex and wants to tell you all about it. After all, she has the technology to do so.

Napkin, despite its nature as a personal zine with retro trappings, is still a thoroughly modern work from the identity of its author to the literal paper it was crafted on. While the utilization of varied technology to tell a story is nothing new (left-leaning political movements have always used technology to some degree), the way in which Monir brings Napkin to life specifically connotes the more nostalgic efforts of the 1980s, with its use of scanned pictures, handwritten notes, and Polaroid pictures, while using modern language and slang throughout its prose to ground Napkin back into the present. The quality of the risograph work gives the reader the impression of something vintage and messy while still intimate and necessary. The lack of polish that Napkin employs throughout the work leaves the reader with the impression of a friend sharing stories about their sex lives -- the reader is given an in on Monir’s emotional state, which bleeds into the very conceit of Napkin itself -- that Carta Monir wants to tell you some stuff about her sex life and her feelings about her sex life. As such, Carta’s work being a third-wave feminist work (in this case) means that Carta is centered in her gender and sexuality in a healthy way, leveling the playing field by using the medium of risograph printing to get her story across without the need to answer to too many white, cisgender feminists gatekeepers in the more traditional publishing world. By seizing the means of production to tell her own narrative, Monir exemplifies that she can and will discuss topics such as sex, gender and sexuality without the need to dehumanize herself to get her point across; sexy without being a sex object, important without being pedestaled. In Napkin, Carta Monir is a person who happens to like having sex and wants to tell you all about it. After all, she has the technology to do so.

Interviewer: You talk about your own experiences with sex, sexuality, and gender a lot throughout many of your works, and Napkin certainly was no exception. What gives you the gumption to continue to be so vulnerable with such a touchy subject?

Carta Monir: I talk about this a fair amount, but honestly I mostly see it as circumstantial. If my mom were alive, I don’t know if I would be working on projects like this. This kind of work would really upset my family, if my family still existed the way it did a few years ago. But since it doesn’t… I don’t know, it just doesn’t feel like I have much to be scared of. I’m making the kind of work that I want to; living the kind of life that I want to.

Interviewer: Have the responses to your comment cards affected your self-image?

Carta Monir: People were very positive! Maybe more positive than I anticipated. I thought I’d get maybe a few more critical comments? But if anything I left the project feeling a little more sure of myself.

The titular napkins of Napkin are a direct reference to the comment cards that are the focal point of the piece, cards on which Monir has had her various sexual partners write responses to their most recent sexual escapade, and as Monir as stated herself, the responses from her various sexual partners has been largely kind and positive. Since much of second-wave feminism had dealt with the idea that women’s bodies are their individual choice, it’s wonderful to see the praxis that third-wave feminists bring up -- that everyone’s bodies are their own individual choice, and that they can and should speak out about their sexual experiences to break the patriarchal stigma that comes along with the learned shame one might have with sex. In a similar vein, while biological sex and gender are not the same thing, in Napkin, Monir goes into her experiences as a transgender woman and how her gender identity has affected her relationship to her own sexual attraction without delegitimizing herself or her gender in the process.

By giving callbacks to older terms of gender and sexual identities that she’s used for both herself and others in the past within the text of Napkin, Carta preemptively shuts down people trying to fetishize her as a transgender woman and/or gender essentialists seeking to deplatform her. In Napkin, Monir never claims that her grasp on gender identity is absolutely perfect -- her aim is to learn from past mistakes and grow from them.

Language around gender and sex changes all the time, and while Monir might still use older terms when describing herself or the people whose gender information she is most privy to, she never uses that information as an excuse for harm or bigotry. Affirming that she is a transgender woman is a welcome modifier for Monir; she recognizes that the various LGBT+ discourse and politics that have brought her to being secure in her own gender might be considered too problematic in the same way they once were. In a similar vein, mentioning and affirming her transness doesn’t make Monir any less of a woman, and publicly stating her trans identity, once again, exemplifies a proponent of third-wave feminism -- that everyone’s bodies are their own individual choice. By centering her narrative on herself in Napkin, Carta Monir acknowledges choice of freedom in gender expression as well as asserting that gender transition is a not a thing to fear or demean, but a natural part of life that deserves to be celebrated. As Monir often says in her work, being trans is a gift, and with Napkin, Monir chooses to share the gift of her body with her lovers and with others - sexual and gender identity very much included.

Interviewer: Has your spouse filled out a comment card?

Carta Monir: Yes they have! It’s in the book.

Now, throughout this essay there has been much discussion on how with the creation of Napkin, Carta Monir uses much of the hard-work won by second-wave feminism and qualifies it through the ongoing current work of third-wave feminism: that is, if your body is your choice, than you can actively choose what to do with your body. With Napkin, Monir simply discusses what she actively does with her body -- choosing to detail many of her sexual escapades, her experiences in polyamory and the importance of maintaining healthy relationships, as well as her own journey with her own gender identity and how she relates her life as a sexual being as it connects to her sense of self .

However, I would like to note that although Monir does discuss many sexual situations in Napkin, she still has a strong sense of personal responsibility that comes from sharing such stories. Many of the titular comment cards she asks her lovers to fill out after a sexual interlude are presented anonymously in Napkin, and Monir goes through great pains to detail that consent is very important in every sexual encounter one might go through. After all, the journey Monir recites in Napkin is ultimately one of self-love, but as with all things, self-love is never truly selfish. Third-wave feminism may have informed the political landscape that Napkin has come out from, but it’s still up to Monir in the end to take responsibility for how she chooses to present herself and others in personal stories. In the ongoing journey of personalizing herself through her sexual exploits, she never dehumanizes her lovers in the process -- being private on some things connotes care, not dishonesty. In the end, media and medium may inform sex and art, but it’s really up to the artist themselves to shape art how they like in the end. And in the end, Monir succeeds in presenting Napkin as two things: Sexy and loving. So please, go give it a read -- just be mindful how you read it.

Interviewer: What would be the number one thing you’d like readers to take away from Napkin?

Carta Monir: Short answer: Be a slut! It’s fun! Longer answer: I think it’s really important to make work about the stuff that scares and interests you most. I feel extremely blessed that the response to Napkin has been so positive. It’s scary to make work like this… but very worthwhile. I guess I’m just making the work that I want to read, as cliche as that is.

Images found in article are from Napkin by Carta Monir © 2019

All images can belong Carta Monir © 2019