Dansker (‘Dane’) is the story of a broken man, trapped in the shadow of the Armenian genocide and by the trauma of his youth. James Pisket was born in 1953 and grew up in the borderlands between Armenia and Turkey. We follow him as he deserts the Turkish army and emigrates to Denmark, where he struggles with a death wish as he embarks upon a life of crime. Key to his survival is the relationship to his neglected children, one of whom, Halfdan (born 1985), is the work’s author.

Dansker is part of a trilogy originally published in Denmark: Desertør (‘Deserter’, 2014), Kakerlak (‘Cockroach’, 2015) and Dansker (2016) and since collected as Dansker-trilogien (‘The Dane Trilogy)’. The first volume won the Danish Ping Award for Danish Comic of the Year in 201, and the French edition of volume three was just bestowed the so-called Series Award at the international comics festival in Angoulême, France—a major recognition. Sadly, we are still waiting for an English-language publisher to sign on.

Educated at the Danish Royal Academy of Arts, Halfdan Pisket spent his youth making noise as part of the musical activist group Albertslund Terrorkorps, as part of which he developed his expressive graphic symbolism, partly through poster art and other paper ephemera, partly through a number of early and ambitious but also overly earnest comics. The Dansker trilogy, however, saw him mature quickly. The rich, lived experience it transcribed was an obvious catalyst. You can see him developing by the page, from an already strong start few readers familiar with his previous work would have expected.

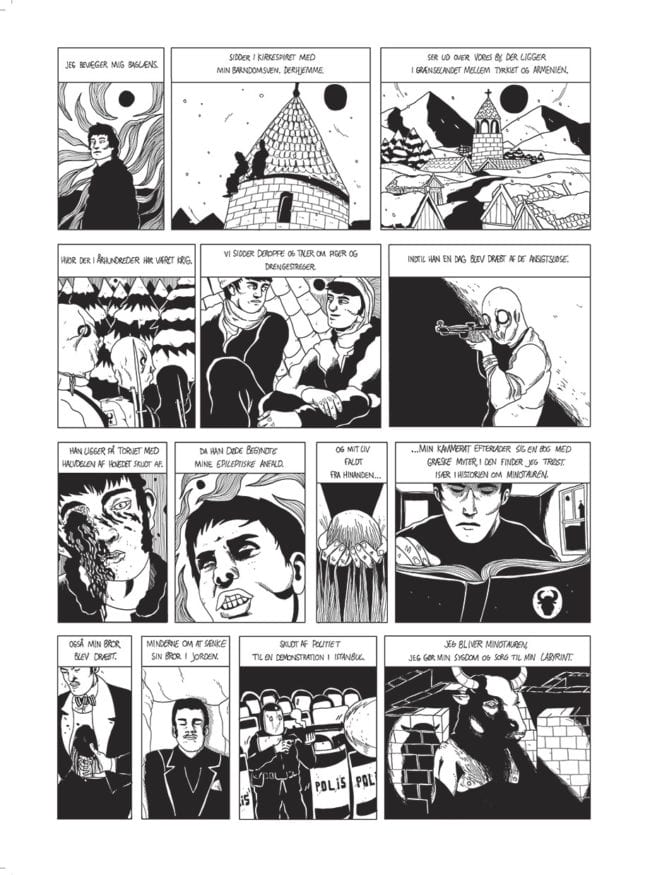

These comics are the result of conversations between father and son. They are characterized by fragmentary, at times almost dream-like narration, is if distilled from deeper, partly suppressed memory. Pisket himself has emphasized that it is a fictional condensation of his father’s experiences, simplified, dramatized, and clarified to ring closer to the truth.

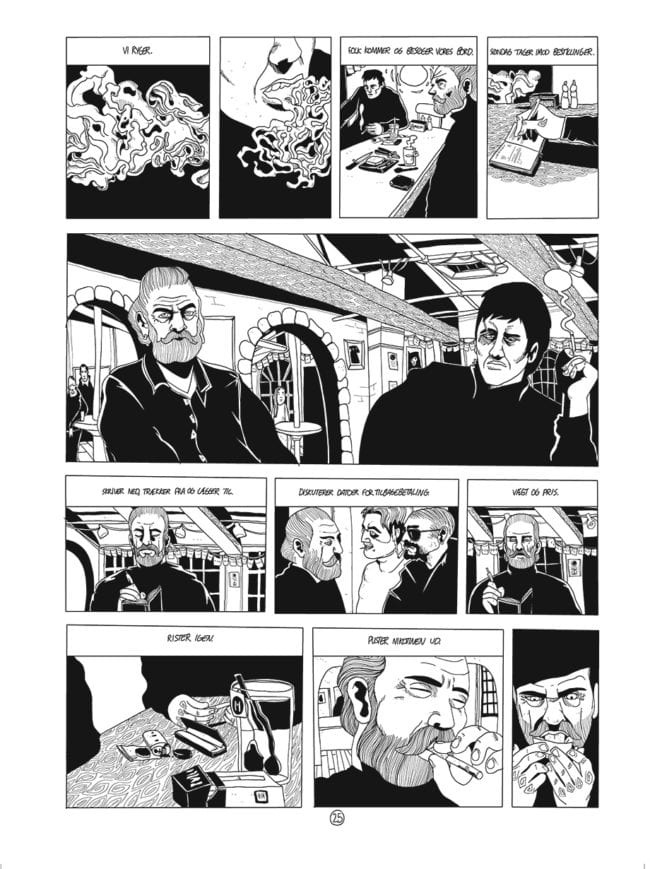

The story is told on tightly paneled pages, drawn digitally with an expressive line, set in stark contrast. Most of his text is his father’s captioned voiceover, with balloons used only for scenes of particularly immediacy. The language is poetically terse: “On the outskirts of the city/the trenches of old wars lined the roads/Soil and skeletons were layered here.” This caption (in my translation) sets the scene on an early page describing James’ hometown; it is otherwise dominated by images of war and pain, with crosses dotting the ground under flowering trees.

This is the town of Kars, in which James Pisket remembers Christians, Muslims and animists living in harmony, in spite of the authoritarian regime in Ankara. He is the son of an Armenian mother and a Turkish father. In the woods outside the city, groups of Turkish conscripts guard the transient border. They are described as “faceless” and depicted with characteristic symbolism as wearing white canvas hoods. Their presence is menacing, reminders—like the bones lining the waysides—of the human catastrophe that everyone tries to forget.

James himself was conscripted and ended up deserting. This landed him in prison, where he was subjected to torture, an experience that we understand continues to haunt him with crushing determination. It profoundly informs his experience as an immigrant to Denmark. Pisket here describes with great immediacy the feeling of not belonging and the isolation that results from suppressing trauma while attempting to live in a society of privilege and plenitude. He grimly exposes the gaps in the country’s world-famous welfare system, but nevertheless asserts his protagonist’s individual responsibility for his life.

James’ erratic course leaves the wreckage of several relationships and neglected children; a hashish-induced haze suppresses epileptic seizures and numbs his crises of conscience alike. The book is rife with lived detail—the greengrocery James manages for a while behind the city’s central station; the morning joints he smokes with colleagues at the wholesale market; the social club he goes on to open nearby, with pool tables, backgammon and Turkish food; the hyper-masculine ethos of Copenhagen gangland. It culminates with shocking violence.

We later find him living in the iconic Copenhagen freetown Christiania during the particularly charged period of gang violence following police crackdown on the drug market there in the late nineties. He supports himself selling hashish, hiding his earnings under the boards in the laundromat that he runs, but he also finds increasing meaning in his erratic relationship with the children he shares with his now alienated ex, Arla: Joshua and Vibe. They are obvious stand-ins for the real-life author and his sister, and constitute James’ lifeline, with parallels drawn to the family we have previously seen him leave behind in Turkey. Despite his obvious neglect, the suggestion seems to be that his salvation might ultimately lie in his particular cultural assumptions about family.

Pisket combines realism and stylization with an acute sense of visual potency: he delineates with equal verve the bricked warp and weft of apartment blocks, the angular white sheen of streetlights in windows at night and—in what is almost a visual signature—pointed dagger-like forms emerging from the eyes and mouths of his characters. Such symbolic devices are essential to his storytelling: the Minotaur and the Labyrinth are a consistent motif, denoting the protagonist’s inner turmoil, while a ominous black sun continuously illuminates his life from a white sky.

The narrative principle of expressive, often symbolic imagery and succinct narration is appropriated from David B’s autobiographical masterwork Epileptic (1996–2003), but Pisket’s images are more detailed, closer to observed reality, and he makes more ample use of deep, albeit often distorted, perspective. As in Epileptic, his confidence visibly grows during the obviously intense creative period in which he drew the story’s almost 400 pages. Where the earlier parts offer lithe and fragile if assertive images that obviously draw on such masters of black-and-white cartooning as Didier Comès and José Muñoz, the imagery gradually develops a greater presence, more amply textured through hatching and with an assertive modernist angularity redolent of Egon Schiele.

The trilogy deals in equal parts with outer, sensed life and inner experience. It is a chilling portrait of broken existence, but is tempered somewhat by warmth, notably in the scenes of father and son. Pisket achieves this in part by the extraordinarily empathetic, moving way in which he portrays himself as seen through the eyes of his father. The only obvious parallel in comics is Dominique Goblet’s unflinching explorations of her family relations.

His art at times seems a bit forced, individual panels overloaded, and the symbolism can comes across as heavy-handed in passages. Least successful is the last couple of chapters, which—very much like the similarly conceived, disappointing end to David B’s Epileptic—comes across as willed and lacking in nuance in a way that contrasts to the inner necessity felt in the rest of the narrative. The promise of redemption it offers its protagonist is earned, both emotionally and narratively, but fails adequately to make us feel with our protagonist how he reaches the point we ultimately see him at.

None of this, however, changes the impression that we are dealing with a significant and timely contribution to European immigrant literature, nor does it diminish the power of Pisket’s portrait of his father. An extraordinary work of family history, memory, and empathy.