1. Who is America’s Best Comic-Book Critic?

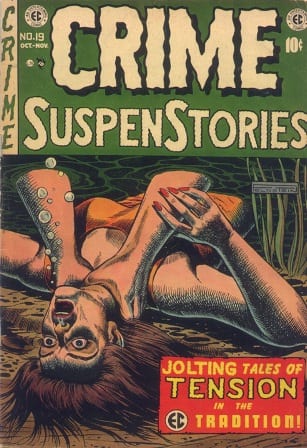

Fredric Wertham has long been America’s greatest comic-book villain, an evil Freudian genius, so the argument goes, who single-handedly almost destroyed one of our country’s most beloved art forms in his quest to prove how deeply perverse the comics of the ’40s and early ’50s were, how effortlessly they twisted pliable young minds. Dr. Wertham operated toward the end of what’s now called the “Golden Age” of American comics (c. 1933-1956), the halcyon days of kid’s funny books, whose pages overflowed (we seem to forget) with bondage, rape, stabbings, bullet holes, pistol whippings, mutilation, dismemberment, hypodermics in the eye, patriotic gore, and 1001 other kinds of sadism.

(If Wertham ended the Golden Age, is he the accidental father of the anemically chaste Silver Age superhero, who began his journey into the heart of comic fandom in 1956?)

The value of Wertham’s 1954 Seduction of the Innocent is almost always reduced to a pro-con argument over its claim that crime comics damaged child readers — unsurprisingly, most folks fall into the “Wertham is Wrong” camp. Adding to comic-lovers’ reasons to detest the psychiatrist, we recently learned that he was a sloppy researcher who played fast and loose with the data.*

What’s missed in these debates is a fuller understanding and appreciation of Wertham, not as an anti-comics crusader, but as a comics critic. When I first read Seduction of the Innocent, I was taken by how comprehensive, almost exhaustively so, it is. Wertham talks not only about plot, images, narration, and dialogue, but about seemingly every aspect of comic books and the culture in which they were created and consumed. He tackles how they’re produced, printed, and disseminated; their non-story elements (such as advertisements and editorials); child readers’ responses to them; and public reactions in the press and educational community. His presentation of these subjects is, as many have noted, disorganized and repetitive, but his impressive interpretive scope more than compensates. While readers are certainly right to criticize his many faults and biases,** I’m not really interested in the validity of his findings. It’s Seduction of the Innocent’s wide-ranging approach that makes Wertham one of comics' heroes.

Here’s a short survey of his extensive ‘methodology’:

Narrative

When Wertham interprets a comic, he assumes that every narrative/visual element matters. So he’ll discuss plot, dialogue and narration, art and coloring, the presence of familiar character types, the use of splash pages, and even hand lettering and typography (which words are in what style and size, etc . . .). He performs numerous short close readings of scenes, typically from a Freudian perspective that addresses why an image or scene will trigger a child’s drives and anxieties. Wertham also undertakes quantitative studies — e.g., what types of violent actions are represented and how many times each appears per story and book — and argues that repeated expose to such visual sadism causes real harm.

For each element he examines, he asks what it means for the comic and its juvenile reader, investigating how editorial-artistic choices function together to create the ‘sensationalizing’ effect that comics can have on a child’s body and psyche. Wertham famously argues that artists (perverts that they are . . .) use sexually-charged “pictures within pictures” (hidden drawings animated by a subliminal pornographic mischievousness) to excite young readers.

Paratextual

Always interested in “the paratext,” Wertham looks at non-story aspect of the printed object, such as materials used in the printing process, cover image and words, the series’ title, along with text pieces and advertising. Particularly concerned with interactions between story content and paratextual elements, Wertham focuses on ads that address boy and girl readers’ sense of their own masculinity or femininity, talking about how the ads, the comic’s imagery, and its plots reinforce each other by dramatizing (and thus encouraging) the same anxieties. He also explores the arrangement of discrete elements, such as the location of a publisher’s defenses of its product. For Wertham (and me), the standard practice of following a story of mind-bending graphic gore with a throwaway tag line like “Then the criminal went to jail, so crime doesn’t pay, kids” seems a little disingenuous. Publishers care about cash, not kids.

Identity Issues and Social Contexts

Thematically, his topics range extensively to include important issues such as race, gender, sexuality, class, living conditions, and family (adult-child and sibling) relationships. He explores these issues as they appear in the lives of comic-book characters and comic-book readers, connecting crime narratives to developments in contemporary culture, such as a rise in violence and juvenile delinquency.

Media/Medium Comparisons

He frequently defines his subject by talking about crime comics’ connection to other forms of entertainment, such as non-crime comics, comic strips, children’s books, adult fiction, movies, Classic Comics and the literature they adapt. Unlike those who insist that comics shouldn’t be compared to other media (they’ll say things like, “Comics are their own art form and comparisons broadcast an anxious desire to elevate the form by comparing it to Literature and Film”), Wertham understands a simple fact: specific comparisons aid in understanding, analysis, and judgment.

Reader Reception

Wertham talks in detail about children’s readings habits: how many comics they read and the ways in which high circulation of current and back issue among friends affect both a child’s exposure and total readership numbers. Studying comics’ effect on literacy, he shows that children of different ages interact with comics differently: some read the text while others ignore it, with many of all ages focusing solely on meanings conveyed by the semi-pornographic imagery. After Wertham and his staff interview child readers, he connects these responses to the child’s “reading grade,” intellectual abilities, and social conditions. As a Freudian, he’s intensely interested in children’s fantasy lives and parental beliefs (often incorrect) about their children’s reading habits and interest in comics. Concerned with children’s emotions and social interactions, he focuses on needs and desires that these comics ignore or meet. Ultimately, he argues that the repetitious and disposable nature of such violent, misogynistic, and fascistic comics, create a physically addictive desire to consume more: crime comics are a visual drug.

Production and Cultural Reception

Looking at publishers’ claims, especially public defenses of their products, Wertham compares these claims to what actually happens in the comics, finding publishers’ arguments wanting. SOTI addresses circulation numbers and comic producers’ self-represent in a comic’s indicia (the location of publication information); they try, he believes, to conceal their business’s name to ensure anonymity and thus avoid responsibility and publicity. Wertham also talks about the writers/artists who create the books and their motivation for doing so (often only money); mainstream comics, he believes, are non-artistic, editorially-driven corporate product. Seduction of the Innocent surveys numerous arguments about comics and children in the popular press as written by parents, educators, social critics, and medical professionals, putting these arguments in the context of trends in child development/behavior and Wertham’s readings of comics.

So:

I can’t think of another comics study that employs so many different methods. Because of this, put me in the pro-Wertham camp. It's hard not to appreciate someone who takes comics so seriously and studies them from so many perspectives: evaluative, psychoanalytic, ethical, political, sociological, materialist, paratextual, production history, reader reception, plot-based, identity-issue based (class/gender/sexuality), etc . . .

Thus:

Q: Who is America’s Best Comic-Book Critic?

A: Fredric Wertham

2. What is the Best Way to Write Comics Criticism?

Like Wertham, maybe . . .

If comics are a distinct “medium of expression,” it makes sense that the best criticism will explore a work’s use of properties that make a comic a comic and not, say, a novel, such as artwork or page layouts, right? Wrong. I’m always puzzled when readers argue that, to be legit, a discussion must tackle these kinds of topics; we do something wrong, we’re told, when we talk only about a comic’s plot (isn’t this a key reason most humans read books and comics, watch movies, etc?). Of course, I’m all for art-centric analysis. I’m still waiting for someone to write “The Emotional Contours of Jack Sparling’s Brush Technique in Late Dell Comics.” (I love the under-discussed, underrated Sparling, a master of the quick and scratchy ink line!)

Readings that center on non-comicy elements are often called literary. I wonder, though, if there’s really any such thing as a literary reading of a comic. First of all, I don’t know what the word means (and suspect it doesn’t really mean much); but if a literary reading is one that ignores the art, then I'm a little confused. In many narrative comics, the story is often communicated through the art; so even a literary reading takes art into account in some way. And because “non-literary” things like print advertisements and TV commercials often have a plot, a close and meaningful link between literary and story might not be possible.

I think that the “cause of comics criticism” might benefit from a ban on words like literary and literariness, etc. People often use them in vague, shifting, and at times idiosyncratic ways. If critics had to communicate without these words — if they used a less abstract vocabulary when creating or characterizing interpretations — I’m pretty sure all of us would benefit.

I often write criticism that addresses the comicy aspects of comics — visual and/or formal elements — but see no reason to assume this is better than any other approach, literary or otherwise. And why does method matter: as long as the critic doesn’t lie or get facts wrong, then who cares?

So, perhaps the best way to write criticism is to employ one of the methods that America’s best critic, Fredric Wertham, used: evaluative, psychoanalytic, ethical, political, sociological, materialist, paratextual, production history, close reading, reader reception, plot-based, identity-issue based, quantitative, etc . . .

Or just use any method you like.

Thus:

Q: What is the Best Way to Write Comics Criticism?

A: Any way that’s smart, funny, insightful, etc . . .

So:

When writing about comics, please consider exploring topics like the following:

A comic’s dialogue – just the dialogue.

A comic’s dialogue in relation to its character’s facial expressions.

The dialogue in a comic you like compared to that of a comic you don’t like.

The dialogue in a film you like compared to that of a comic you don’t like.

The plot – just the plot.

Gil Kane’s chins (and/or other cartoonists' characters' body parts).

The play of shapes and gestures on a single page.

The play of shapes and gestures on a single page in relation to plot and art.

The use of ”camera angles.”

The number of times The Hulk smashes the ground in comics drawn by Herb Trimpe

(you may want to look at some Keown/David Hulk issues for comparison).

Three cartoonists’ approaches to lettering.

Three mid-1970s DC artists’ approaches to inking.

Gender politics; for example, in early 1990s alternative and mainstream comics.

How a cartoonist poses his main characters and relate this to another relevant issue.

Fashion / clothing. (In one comic; in one artist's work; in one company's comics during a given year.)

Production markings (those not intend for reproduction) on an artist’s original art.

Uses / meanings of a given word in the work of a comics writer.

The relationship between a comic’s advertising and its narrative (a la Wertham).

The work of Freud, Nietzsche, Marx, etc. . . .

Critical Race Theory, post-colonial theory, ecofeminist theory, etc. . . .

Why older printing and coloring methods led to way more cool-looking comics.

The comic in terms of the creator’s life, work, etc. . . .

Page layouts in early 1940s superhero comics.

The virtues of Neo-Nostalgia.

How a cartoonist sets up gags and action sequences and what he or she could learn from Carl Barks's comics.

The history of thought balloons and related internal-narration devices, from 1657 to today.

Punctuation in comics versus prose + poetry . . .

Why Dondi’s face has always disturbed you.

Why all superhero comics are not fascistic, despite the fact that some folks continually say they are when they clearly aren’t, like think about The Inferior Five for instance.

Why the comic sucks; why you love it; what a character means to you; why you like comics better than books without drawings, etc. . . .

And so on.

________

NOTES

*See information on Carol Tilley's recent work here.

**Though fairly progressive on issues of race, Wertham was reactionary when it came to sexuality; like many psychiatrists of his time, he saw homosexuality as a deviant form of behavior.