This column takes the pulse of the alt-comics world by way of a traditional method: evaluating anthologies. There are anthologies published by local collectives, acting as statements for small-press outposts. There are themed anthologies, whose success generally depends on how skillful the editor is in coming up with a theme that produces a coherent work without soliciting too much repetitive material. There are anthologies built around music and music scenes, anthologies built around variations on genres like horror, science fiction, and fantasy. There are broadsheets and anthologies built around the taste and reach of individual editors. I have purposefully excluded longer anthologies, preferring to focus on smaller-scale, minicomics productions.

Themed Anthologies

Pratfall, edited by Rob Kirby. TCJ contributor Kirby is skilled at putting together anthologies. He uses clever themes that allow for enough diversity to avoid repetition but also hold together well enough to prove cohesive. It helps that Kirby's experience in both the queer-focused and mainstream alt-comics worlds gives him an especially broad and interesting variety of artists from which to choose. The theme in Pratfall is embarrassing spills and injuries, and the cartoonists simply get right to the point. Highlights include a John Porcellino story concerning a teenage skateboarding accident that's unusually visceral for him, an exquisitely-drawn Tessa Brunton story about falling down an escalator as a child on vacation, an epic Cara Bean entry about falling out of a ski lift as a teen, and Kirby's own tales of injury on the job as a waiter. The most pleasant surprise is Becky Hawkins, whose story of crashing a quad-bike into a tree-cactus hilariously focuses on the spectacle of both the event and the cosmetic damage that she took. The anthology in general takes a lighthearted tone and focuses on sheer entertainment.

Pratfall, edited by Rob Kirby. TCJ contributor Kirby is skilled at putting together anthologies. He uses clever themes that allow for enough diversity to avoid repetition but also hold together well enough to prove cohesive. It helps that Kirby's experience in both the queer-focused and mainstream alt-comics worlds gives him an especially broad and interesting variety of artists from which to choose. The theme in Pratfall is embarrassing spills and injuries, and the cartoonists simply get right to the point. Highlights include a John Porcellino story concerning a teenage skateboarding accident that's unusually visceral for him, an exquisitely-drawn Tessa Brunton story about falling down an escalator as a child on vacation, an epic Cara Bean entry about falling out of a ski lift as a teen, and Kirby's own tales of injury on the job as a waiter. The most pleasant surprise is Becky Hawkins, whose story of crashing a quad-bike into a tree-cactus hilariously focuses on the spectacle of both the event and the cosmetic damage that she took. The anthology in general takes a lighthearted tone and focuses on sheer entertainment.

Cringe, edited by Peter S. Conrad. Published by the increasingly ambitious Birdcage Bottom Books and designed by BBB publisher J.T. Yost, this "anthology of embarrassment" makes a nice companion piece to Pratfall. There's an interesting cross-section between young and veteran cartoonists, as well as a mix between minicomics makers, illustrators, and web cartoonists. While most of the stories are played strictly for laughs, there are also some more thoughtful narratives. Geoff Vasile's story about meeting a date through the internet is a deeply intimate look at his own low self-image. The date gets weirder and weirder, and he finally stops it from getting physical. The eventual reveal at the end of the story doesn't come as a huge shock, but it does serve to validate his instincts. Sam Henderson's comic about his epileptic seizures and the unwelcome and unwarranted attention they draw is a departure for the artist. The same goes for Box Brown's strip about his odd erstwhile habit of eating light bulbs, and Steve Lafler's thinly-veiled autobio strip about ratting out a friend regarding a fire alarm prank. Fred Noland's strip about his humble roots and his beloved Crayola crayons getting destroyed begins with an air of righteous fury but ends with the artist feeling sorry for the perpetrator. Really, with the exception of Lizz Lunney's hilarious "Levels of Embarrassment" strip, the best stories in the book are those that take the subject seriously, rather than just provide an opportunity to rework an old story as a gag.

Cringe, edited by Peter S. Conrad. Published by the increasingly ambitious Birdcage Bottom Books and designed by BBB publisher J.T. Yost, this "anthology of embarrassment" makes a nice companion piece to Pratfall. There's an interesting cross-section between young and veteran cartoonists, as well as a mix between minicomics makers, illustrators, and web cartoonists. While most of the stories are played strictly for laughs, there are also some more thoughtful narratives. Geoff Vasile's story about meeting a date through the internet is a deeply intimate look at his own low self-image. The date gets weirder and weirder, and he finally stops it from getting physical. The eventual reveal at the end of the story doesn't come as a huge shock, but it does serve to validate his instincts. Sam Henderson's comic about his epileptic seizures and the unwelcome and unwarranted attention they draw is a departure for the artist. The same goes for Box Brown's strip about his odd erstwhile habit of eating light bulbs, and Steve Lafler's thinly-veiled autobio strip about ratting out a friend regarding a fire alarm prank. Fred Noland's strip about his humble roots and his beloved Crayola crayons getting destroyed begins with an air of righteous fury but ends with the artist feeling sorry for the perpetrator. Really, with the exception of Lizz Lunney's hilarious "Levels of Embarrassment" strip, the best stories in the book are those that take the subject seriously, rather than just provide an opportunity to rework an old story as a gag.

Screw Job #1, edited by Paul Lyons. This is a pro-wrestling-themed comic brought to you by one of the editors of the great Monster anthology. It's as full of blood 'n guts as the sport used to be back in the day, leading off with a clever Box Brown story about legendary "bleeder" Abdullah the Butcher and a lawsuit in which another wrestler accused him of giving him Hepatitis C. The best pieces in the book are the most far-out: the wildly violent story by Lale Westvind (about a female wrestler who literally rips out the spines and faces of an entire cadre of male wrestlers) and Mickey Zacchilli's ode to another hyper-violent female wrestler that almost becomes abstract in spots. Westvind's muscular style is expressive but centered in rock-solid anatomical detail, while Zacchilli is more about the interior life of the wrestler. Other highlights include Josh Bayer's eloquent odes to an all-time-great "talker," manager "Classy" Freddie Blassie. Bayer is clearly fascinated by the psychology of the "heel," how they choose to get under the skin of the crowds, and how it all connects to bloviating rhetoric in general. The most poetic piece is Brian Ralph's "Folding Chair", which has a folding chair emphasized in every panel, with wrestling action in the background in a lighter tone. This book is obviously a must for wrestling fans, but fans of the individual artists will find much to enjoy.

Screw Job #1, edited by Paul Lyons. This is a pro-wrestling-themed comic brought to you by one of the editors of the great Monster anthology. It's as full of blood 'n guts as the sport used to be back in the day, leading off with a clever Box Brown story about legendary "bleeder" Abdullah the Butcher and a lawsuit in which another wrestler accused him of giving him Hepatitis C. The best pieces in the book are the most far-out: the wildly violent story by Lale Westvind (about a female wrestler who literally rips out the spines and faces of an entire cadre of male wrestlers) and Mickey Zacchilli's ode to another hyper-violent female wrestler that almost becomes abstract in spots. Westvind's muscular style is expressive but centered in rock-solid anatomical detail, while Zacchilli is more about the interior life of the wrestler. Other highlights include Josh Bayer's eloquent odes to an all-time-great "talker," manager "Classy" Freddie Blassie. Bayer is clearly fascinated by the psychology of the "heel," how they choose to get under the skin of the crowds, and how it all connects to bloviating rhetoric in general. The most poetic piece is Brian Ralph's "Folding Chair", which has a folding chair emphasized in every panel, with wrestling action in the background in a lighter tone. This book is obviously a must for wrestling fans, but fans of the individual artists will find much to enjoy.

Lovers Only, edited by Mickey Zacchilli. Billed as "Teen Romance Comix", this anthology has a decidedly different bent from what have normally been considered to be romance comics. Cathy G. Johnson's story is incredible: a swirling mass of greens and reds that echo the emotional confusion and tumult of its main character. It's a story about wanting same-sex friendships to be more, about the pain of gender conformity, and about the struggle to burst out of categories and binaries that extend to mental health. However, it's told with blunt authenticity that reflects these issues and more without resorting to didacticism, and ends with the salient lines "There is no conclusion. There is no such thing as closure." Zacchilli's piece is about a single time, place, and experience that represents an entire era, as the main character's female friend starts to get weird with her in asking her if a particular boy gets her hot, followed by her getting high. Zacchilli does a masterful job of using a minimum of lines and colors for a powerful effect, like a series of close-ups on the main characters eyes as she gets high, or a telling pose from that best friend that reveals more than words ever could. If Johnson and Zacchilli's comics are "hot" in terms of imagery and expressiveness, then Sophia Foster-Dimino's piece is "cool" in comparison, with stripped-down lines and figures belying the mix of love, lust and self-hatred that the main character feels. This anthology hits hard, hits quick, and doesn't outstay its welcome.

Lovers Only, edited by Mickey Zacchilli. Billed as "Teen Romance Comix", this anthology has a decidedly different bent from what have normally been considered to be romance comics. Cathy G. Johnson's story is incredible: a swirling mass of greens and reds that echo the emotional confusion and tumult of its main character. It's a story about wanting same-sex friendships to be more, about the pain of gender conformity, and about the struggle to burst out of categories and binaries that extend to mental health. However, it's told with blunt authenticity that reflects these issues and more without resorting to didacticism, and ends with the salient lines "There is no conclusion. There is no such thing as closure." Zacchilli's piece is about a single time, place, and experience that represents an entire era, as the main character's female friend starts to get weird with her in asking her if a particular boy gets her hot, followed by her getting high. Zacchilli does a masterful job of using a minimum of lines and colors for a powerful effect, like a series of close-ups on the main characters eyes as she gets high, or a telling pose from that best friend that reveals more than words ever could. If Johnson and Zacchilli's comics are "hot" in terms of imagery and expressiveness, then Sophia Foster-Dimino's piece is "cool" in comparison, with stripped-down lines and figures belying the mix of love, lust and self-hatred that the main character feels. This anthology hits hard, hits quick, and doesn't outstay its welcome.

Horror

Insect Bath, edited by Jason T. Miles. Distributed by the Profanity Hill collective, this comic has a visceral but cerebral approach that is truly unsettling. This is a horror anthology done in what I refer to as the "immersive" style of comics. It's a style that makes its decorative aspects part of its narrative, creates its own visual logic and demands active reader interaction. It's not a passive form of storytelling that gently leads the reader across the page, but rather a style that's murky and works only on its own terms. It's not surprising that Miles planned to do this anthology with the late Dylan Williams, because Williams' Sparkplug Comic Books was a champion of this style. Miles' own strip in the anthology acts as a story of primordial ooze, birth and rebirth, as well as a howl against the void. There are also stories conflating sexual discomfort with body horror and madness from like Zach Hazard Vaupen and Alex Delaney.

More challenging is Juliacks' suffocating story about bodies being manipulated, thrown against walls, played as puppets, drowned and defecated upon; the denseness of her line and the near-poetic nature of her decorative text create a powerfully oppressive atmosphere. Contrast that to Noel Freibert and Sammy Harkham, who turn everyday experiences into lethal, terrifying, but ultimately inexplicable events; this is the horror of nihilism. That makes a neat contrast to the horror of absurdity, as seen in the comics of Max Clotfelter, Eamon Espey, and Matthew Thurber. Clotfelter takes the sort of underground scumbag character that frequently appears in his comics and puts him through a scatological but ultimately redemptive series of events. Espey's silent work begins with a city street's sewer, but ends with what appears to be a sort of creation myth. Thurber's grotesquely hilarious and clear-line drawings connect some hard and real talk about racism with the absurd premise about a virus that causes heads to explode when confronted with racial tension. At just thirty-two pages, this anthology manages to run the gamut of horror genre styles without ever devolving into cliché.

Hellbound 5: End of Comics. Published by River Bird Comics, this is the last in a series of attractive and fairly conventional horror anthologies. The stories and styles in this volume are actually more idiosyncratic than those in many of the other volumes. Consider Ben Doane's "Monster Hunt", for example. Though it (somewhat clumsily) employs the same single tone of red that all the other stories do, the stripped-down line and considerable use of negative space make this story (reminiscent of Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery" in some ways) atypical of standard horror fare. On the other hand, Stephen Cartisano and Ellen T. Crenshaw's "The Death of Love" puts that red to good use in a vampire story with a twist, one that openly calls out the so-called "eroticism" of vampire fiction as thinly-disguised rape fantasies. G.P. Bonesteel's "Blood and Breakfast" is another example of a distinctly cartoony stylist telling a story against style about two monstrously murderous psychopath siblings. Its nihilism is understated and deadpan, making its ending all the more horrific. The EJ Barnes/Clayton McCormack "Consummation" pokes fun at the romance genre in a manner that's fairly obvious, reminiscent of the Robbie Williams video for "Rock DJ". This last volume of Hellbound, like all the others, is uneven but willing to take risks.

Hellbound 5: End of Comics. Published by River Bird Comics, this is the last in a series of attractive and fairly conventional horror anthologies. The stories and styles in this volume are actually more idiosyncratic than those in many of the other volumes. Consider Ben Doane's "Monster Hunt", for example. Though it (somewhat clumsily) employs the same single tone of red that all the other stories do, the stripped-down line and considerable use of negative space make this story (reminiscent of Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery" in some ways) atypical of standard horror fare. On the other hand, Stephen Cartisano and Ellen T. Crenshaw's "The Death of Love" puts that red to good use in a vampire story with a twist, one that openly calls out the so-called "eroticism" of vampire fiction as thinly-disguised rape fantasies. G.P. Bonesteel's "Blood and Breakfast" is another example of a distinctly cartoony stylist telling a story against style about two monstrously murderous psychopath siblings. Its nihilism is understated and deadpan, making its ending all the more horrific. The EJ Barnes/Clayton McCormack "Consummation" pokes fun at the romance genre in a manner that's fairly obvious, reminiscent of the Robbie Williams video for "Rock DJ". This last volume of Hellbound, like all the others, is uneven but willing to take risks.

Weird #5, edited by Noel Freibert. If Freibert's tongue was any more in-cheek, it would pop right out of his mouth. His Weird anthology balances blatant attempts at provocation with satires of same. There's also a sense that he's trying to cross the shock-ending creepiness of old EC horror comics with the random, out-there contributions from the '80s anthology Weirdo. There are a number of ink-heavy, blobby-lined strips by Freibert about the police that have the look and feel of naive invective. There are random pornographic images that are meant to be more transgressive than titillating. There's a tremendous amount of sheer noise in this anthology; it's designed to be off-putting and annoying in a way that's clearly calculated and mannered. In between the noise are some excellent comics by Lala Albert (a demented story about a woman starting to produce honey in an intimate location after noticing a bee on her, who later finds herself transformed in the middle of having sex) and Patrick Kyle (a narrative about an obsessive executive). There are odd photo essays, admonitions to declare Weird a danger to the public, and a couple of photos of the end that see a woman literally pissing on a copy of Weird. As a work of provocation, this issue of Weird (which comes in a black pouch the way that pornography might) works mostly on a juvenile level. Freibert's own contributions feel like equivalent of a five-year-old saying "Fuck" to get a reaction. However, there are some genuinely strange moments to be found in the anthology, though Albert's story is the only one truly unsettling.

Weird #5, edited by Noel Freibert. If Freibert's tongue was any more in-cheek, it would pop right out of his mouth. His Weird anthology balances blatant attempts at provocation with satires of same. There's also a sense that he's trying to cross the shock-ending creepiness of old EC horror comics with the random, out-there contributions from the '80s anthology Weirdo. There are a number of ink-heavy, blobby-lined strips by Freibert about the police that have the look and feel of naive invective. There are random pornographic images that are meant to be more transgressive than titillating. There's a tremendous amount of sheer noise in this anthology; it's designed to be off-putting and annoying in a way that's clearly calculated and mannered. In between the noise are some excellent comics by Lala Albert (a demented story about a woman starting to produce honey in an intimate location after noticing a bee on her, who later finds herself transformed in the middle of having sex) and Patrick Kyle (a narrative about an obsessive executive). There are odd photo essays, admonitions to declare Weird a danger to the public, and a couple of photos of the end that see a woman literally pissing on a copy of Weird. As a work of provocation, this issue of Weird (which comes in a black pouch the way that pornography might) works mostly on a juvenile level. Freibert's own contributions feel like equivalent of a five-year-old saying "Fuck" to get a reaction. However, there are some genuinely strange moments to be found in the anthology, though Albert's story is the only one truly unsettling.

Science Fiction/Fantasy

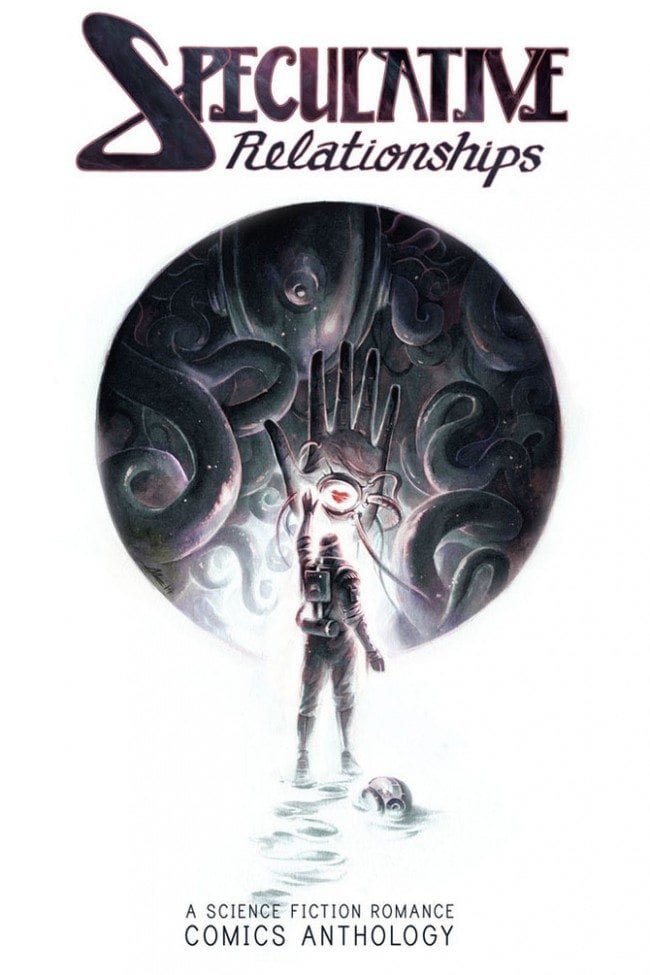

Speculative Relationships, edited by Tyrell Cannon and Scott Kroll. This is actually a romance anthology in sci-fi clothing (it's billed as "a science fiction romance comics" anthology). Editor Cannon plays that connection for laughs, grafting a sci-fi plot on to a stereotypical 1950s romance comic. While that sort of parody is good for a mild chuckle, a book full of such stories would have quickly gotten old. Instead, the book revolves around comics that are genuinely devoted to telling stories about longing, connection, and risks taken in the name of love. The shortness of some of the stories makes them seem a bit on the shallow side, but there are two standouts. First is Isabella Rotman's "The Dream Program", about the clever conceit of a spaceship's computer falling in love with an astronaut in deep sleep, thrusting itself into her dreams, and desperately trying to prevent the ship from reaching its actual destination. The full-page spreads are elegant, emphasizing Rotman's many decorative flourishes as part of the overall aesthetic of the computer's dream world. The other interesting story is Scott Kroll's "4 Out Of 5", which is about sexual identity and polyamory among a species of squid-like alien creatures. This is a case where the sci-fi trappings work as a clever metaphor rather than simply as sci-fi dressing or tired cliché (like robots in love).

Future Shock 1-3, edited by Josh Burggraf. There's been some discussion about how Metal Hurlant/Heavy Metal is influencing a new generation of cartoonists. The artists included here are cartoonists working in a trippy, heavily stylized version of science fiction, with Moebius and Philippe Druillet as their touchstones. Editor and heavy contributor Burggraf (his use of cutesy alternate spellings of his names like "Josh Beef Hats" gets old quick) sets the pace in his cartoony, brightly colored, and fairly straightforward stories that are great to look at but mostly forgettable. More interesting is the work of series regulars like Anuj Shrestha and William Cardini, whose own distinctive styles manage to mesh with Burggraf's overall aesthetic while still staying true to their own ideas and themes. Cardini draws deliberately artificial-looking lines with his computer, moving past his obvious Mat Brinkman influence to thrust the reader into the viewpoint of a radically different way of perceiving the universe. For Shrestha, it's all about how disrupting one's everyday perceptions of the world--no matter how strange that world might be to the reader--can be genuinely terrifying. Mixing that in with body horror in the form of vegetation mimicking animal life and unusual forms of reproduction allows him to create visually unsettling narratives that are made all the more frightening because of their emotional content. While there's certainly a good bit of filler to be found in this anthology, the best pieces are visually exciting and thematically interesting.

Future Shock 1-3, edited by Josh Burggraf. There's been some discussion about how Metal Hurlant/Heavy Metal is influencing a new generation of cartoonists. The artists included here are cartoonists working in a trippy, heavily stylized version of science fiction, with Moebius and Philippe Druillet as their touchstones. Editor and heavy contributor Burggraf (his use of cutesy alternate spellings of his names like "Josh Beef Hats" gets old quick) sets the pace in his cartoony, brightly colored, and fairly straightforward stories that are great to look at but mostly forgettable. More interesting is the work of series regulars like Anuj Shrestha and William Cardini, whose own distinctive styles manage to mesh with Burggraf's overall aesthetic while still staying true to their own ideas and themes. Cardini draws deliberately artificial-looking lines with his computer, moving past his obvious Mat Brinkman influence to thrust the reader into the viewpoint of a radically different way of perceiving the universe. For Shrestha, it's all about how disrupting one's everyday perceptions of the world--no matter how strange that world might be to the reader--can be genuinely terrifying. Mixing that in with body horror in the form of vegetation mimicking animal life and unusual forms of reproduction allows him to create visually unsettling narratives that are made all the more frightening because of their emotional content. While there's certainly a good bit of filler to be found in this anthology, the best pieces are visually exciting and thematically interesting.

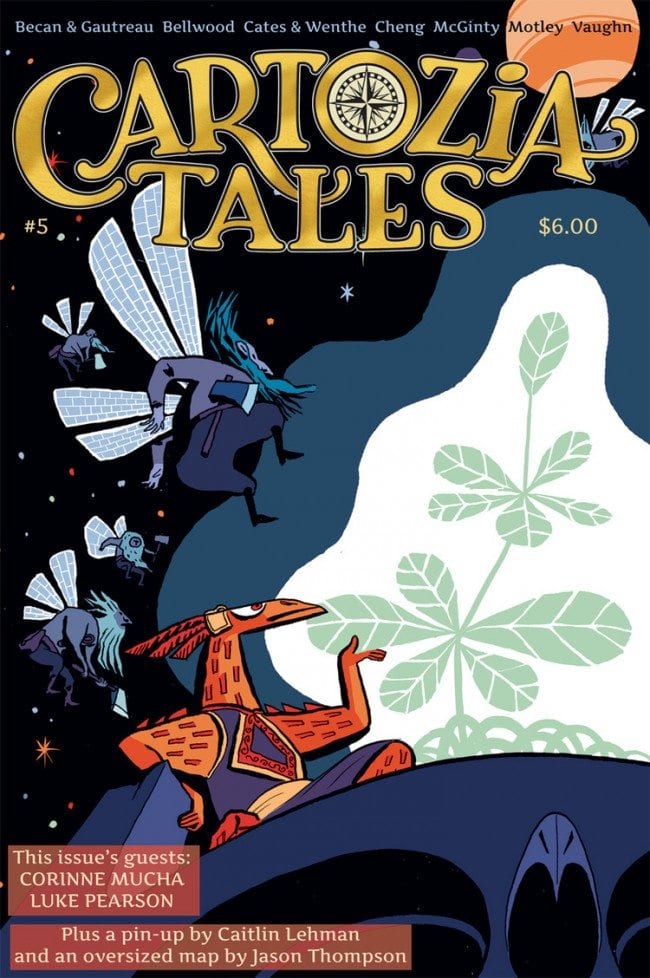

Cartozia Tales 5-6, edited by Isaac Cates. This is an all-ages anthology built on a collaborative model, where characters are rotated on an issue-to-issue basis to new cartoonists. With a steady roster of artists along with a couple of guests each issue, Cates manages to keep up a remarkable sense of issue-to-issue continuity. That's partly because of the collaborative nature of the writing and art, Cates' steady editorial hand, and the fact that most of the artists share a smooth, cartoony style that reduces dissonance for the reader. This is especially important since there are so many serial stories. The one visual exception is T. Motley, whose scratchy and cluttered style is jarring. The other clever conceit of the series is that its adventures are based on location as much as they are on the characters themselves, as the cartoonists actually swap locations on the map of the area rather than the actual characters. The superstar of the book is Shawn Cheng, whose crisp and bold line stands out even amidst guest stars like Luke Pearson and Dylan Horrocks. Lucy Bellwood and Lupi McGinty's contributions are among the best-crafted on an issue-to-issue basis. The stories and characters in Cartozia Tales are clever, complex, and in general surprisingly ambitious for an all-ages book. At the same time, there's enough of a cute factor to hold the attention of younger readers, without falling into the trap of silliness for its own sake.

Collectives And Editor-Driven Anthologies

Runner Runner #3, edited by Greg Means. Means is simply great at publishing beautiful anthologies with polished production values. Published through his own Tugboat Press, this edition of the free anthology has an impressive array of both veteran and young talent. Those who have been missing his old Papercutter anthology should snap this up immediately, as Means once again assembles an array of veteran and fledgling (mostly) west coast talent. Front and center is yet another remarkable short story by Megan Kelso, who has excelled in this area throughout her career. "The Good Witch, 1947" is about a woman working in a factory right after World War II, acting as a single parent. It's implied but never explicitly stated that her husband died during the war, and the story depicts her as successfully juggling the job, motherhood, and carving out time for her own life. Even when she loses her job, the reader gets a sense that she will somehow make it.

Runner Runner #3, edited by Greg Means. Means is simply great at publishing beautiful anthologies with polished production values. Published through his own Tugboat Press, this edition of the free anthology has an impressive array of both veteran and young talent. Those who have been missing his old Papercutter anthology should snap this up immediately, as Means once again assembles an array of veteran and fledgling (mostly) west coast talent. Front and center is yet another remarkable short story by Megan Kelso, who has excelled in this area throughout her career. "The Good Witch, 1947" is about a woman working in a factory right after World War II, acting as a single parent. It's implied but never explicitly stated that her husband died during the war, and the story depicts her as successfully juggling the job, motherhood, and carving out time for her own life. Even when she loses her job, the reader gets a sense that she will somehow make it.

Other highlights include a hilarious Liz Prince set of strips about "domestic bliss" that takes the piss out of the idea, Sam Sharpe's strip about his childhood conflation with math and solving crimes, a poignant anthropomorphic slice-of-life strip by Minty Lewis and Damien Jay, and Elijah Brubaker's funny, demented take on a man who has a pet dog foisted upon him. The comic closes as strongly as it started, with Sam Alden's "Helen". This is a wonderful bit of magical realism, as the titular character goes from twenty-something bitching about her roommates and rushing off to a show to stepping onto a magical subway car that literally slows her down until she reaches her destination, allowing her to create art once again. It's elegant, beautiful (done in Alden's more recent pencil-sketchy style that shifts into full color on the last page, almost like a Wizard of Oz effect) and captures the tone and rhythms of being a particular age in the city.

Short Run: On Your Marks #2, edited by Short Run Seattle. This is an old-fashioned show mini, created for the growing Short Run show. It's a short-and-sweet 25-page minicomic, reflecting the DIY nature of the show (there are no major publishers involved, aside from hometown Fantagraphics). Four of the six participants also attended the 2014 show. The editors (presumably showrunners Janice Headley, Kelly Froh, and Eroyn Franklin) were careful to include a wide variety of styles, from Drew Miller's Gary Panter-inspired, scratchy story about an explorer in a desert at night, surrounded by people hiding in rocks to Jamie Coe's super-slick vignette about young Hercules hanging out with Cerberus as a puppy. Suzette Smith's strip about a couple coming to grips with regard to their individual fears surrounding a gun was as emotionally charged as Scott Longo's story about how lakes are drying up and fires are spreading in the American west because of human intervention. There's also the dream logic of Yuki Sakugawa's couple abandoning all of their technology and the silent images of Anna Saimalaa's figure getting her bruised face entirely wrapped in bandages. This anthology is more of an aperitif than a main event, but it certainly does the job of informing the reader what the show is all about.

Short Run: On Your Marks #2, edited by Short Run Seattle. This is an old-fashioned show mini, created for the growing Short Run show. It's a short-and-sweet 25-page minicomic, reflecting the DIY nature of the show (there are no major publishers involved, aside from hometown Fantagraphics). Four of the six participants also attended the 2014 show. The editors (presumably showrunners Janice Headley, Kelly Froh, and Eroyn Franklin) were careful to include a wide variety of styles, from Drew Miller's Gary Panter-inspired, scratchy story about an explorer in a desert at night, surrounded by people hiding in rocks to Jamie Coe's super-slick vignette about young Hercules hanging out with Cerberus as a puppy. Suzette Smith's strip about a couple coming to grips with regard to their individual fears surrounding a gun was as emotionally charged as Scott Longo's story about how lakes are drying up and fires are spreading in the American west because of human intervention. There's also the dream logic of Yuki Sakugawa's couple abandoning all of their technology and the silent images of Anna Saimalaa's figure getting her bruised face entirely wrapped in bandages. This anthology is more of an aperitif than a main event, but it certainly does the job of informing the reader what the show is all about.

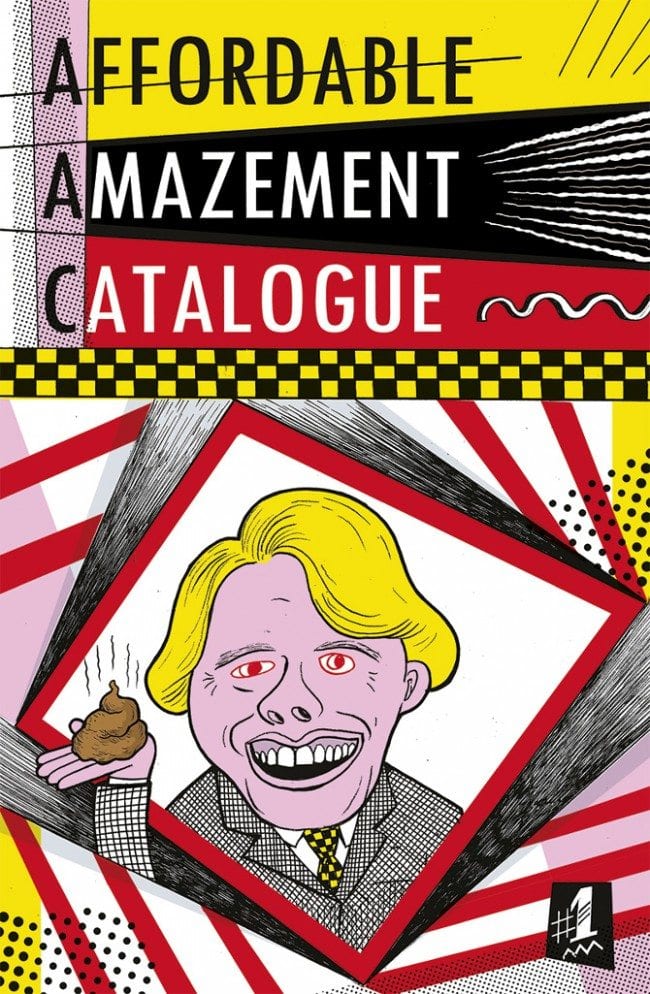

Affordable Amazement Catalogue #1, edited by Lord Hurk. This eccentric and eye-catching European anthology has an underground sensibility but is certainly not limited to one particular aesthetic. With just six artists (all from the UK but one), the anthology allows each to stretch out a bit, as they each touch on the very loosely constructed theme: the weird things one might order from a comic-book, like inflatable coffins ("great for holidaying goths"), onyx roach replicas, and a "worms kit." Tobias Tak's delicate illustrations belie the Rube Goldbergesque silliness of the narrative, while Tanya Meditzky's simple line is used to create a meta-story about Queen Elizabeth using a marketing campaign to muscle out other royal families. Hurk and Chanic's frantic strips hew most closely to the familiar underground aesthetic of visceral storytelling, cartoony art that borders on the grotesque and satire.

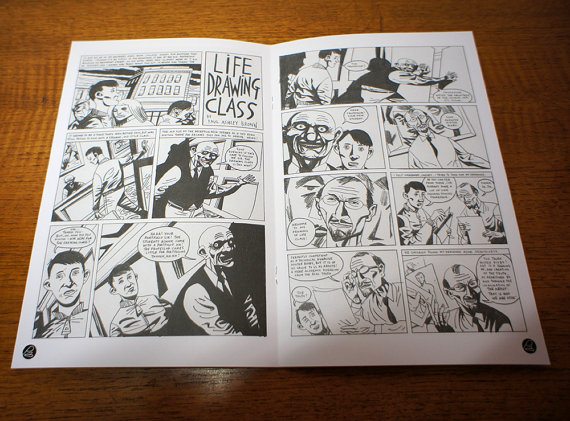

The most intriguing stories were Paul O'Connell's strip about an ordinary man putting on a "toff mask", that is a mask that made him look like a rich person. Just appearing to be rich allowed him to rub shoulders with the government, royalty, celebrities and every rich-person fantasy imaginable, until the brutal, bitter end. The extensive use of negative space and photorealistic drawings create a bizarre, staged atmosphere that mimics the shadows of reality. Paul Ashley Brown's strip about a bizarre life drawing class was my favorite in the book, evoking memories of early Dan Clowes. The maniacal art instructor reminded me a bit of Dr Infinity (from the Dan Pussey stories), while the surreal events surrounding the class were not unlike, in terms of tone, Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron. The story itself owes as much to old EC comics as anything, yet the quirky tone and pencil-heavy approach were entirely Brown's. This anthology relies on comics' past as junk culture meant for children and creates something sophisticated and highly stylized, which has much to do with Lord Hurk's influence in terms of selecting the talent in this issue.

The most intriguing stories were Paul O'Connell's strip about an ordinary man putting on a "toff mask", that is a mask that made him look like a rich person. Just appearing to be rich allowed him to rub shoulders with the government, royalty, celebrities and every rich-person fantasy imaginable, until the brutal, bitter end. The extensive use of negative space and photorealistic drawings create a bizarre, staged atmosphere that mimics the shadows of reality. Paul Ashley Brown's strip about a bizarre life drawing class was my favorite in the book, evoking memories of early Dan Clowes. The maniacal art instructor reminded me a bit of Dr Infinity (from the Dan Pussey stories), while the surreal events surrounding the class were not unlike, in terms of tone, Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron. The story itself owes as much to old EC comics as anything, yet the quirky tone and pencil-heavy approach were entirely Brown's. This anthology relies on comics' past as junk culture meant for children and creates something sophisticated and highly stylized, which has much to do with Lord Hurk's influence in terms of selecting the talent in this issue.

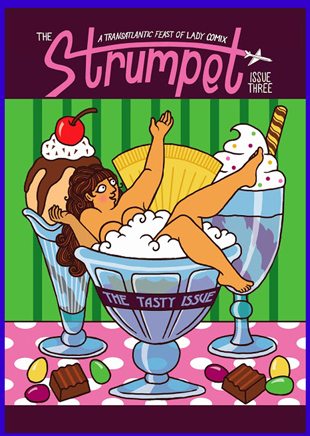

The Strumpet, #3-4, edited by Ellen Lindner. This all-woman anthology series that brings together American and European cartoonists is consistently well-designed and entertaining. It actually reminds me a bit of Lindner's old zine, Little White Bird, in that it mixes comics along with an interview and reviews. The third issue was co-edited with UK cartoonist Kripa Joshi in what was billed as "the tasty issue." While many of the comics were about food, as one might imagine, some did strips about the matter of taste itself. Of the strips about food, two stood out. First was Colleen Frakes' lively and amusing strip about making razor clam cioppino. Most "how to" strips tend to be deadly dull, but Frakes' delightfully chunky line and sense of humor makes this not just readable, but actually entertaining. Joan Reilly's take on being a reluctant meat-eater is amusing and well-drawn; there's a panel where there's a huge burger in the foreground and her teeth are almost comically about to rip into it. Lindner's story adds a whole new level of polish to her work, as demonstrated by her hilarious story about an elaborate break-up. Jennifer Hayden's story about her imaginary lusts and Becky Hawkins' clever take on food and long-distance relationships are also notable.

The Strumpet, #3-4, edited by Ellen Lindner. This all-woman anthology series that brings together American and European cartoonists is consistently well-designed and entertaining. It actually reminds me a bit of Lindner's old zine, Little White Bird, in that it mixes comics along with an interview and reviews. The third issue was co-edited with UK cartoonist Kripa Joshi in what was billed as "the tasty issue." While many of the comics were about food, as one might imagine, some did strips about the matter of taste itself. Of the strips about food, two stood out. First was Colleen Frakes' lively and amusing strip about making razor clam cioppino. Most "how to" strips tend to be deadly dull, but Frakes' delightfully chunky line and sense of humor makes this not just readable, but actually entertaining. Joan Reilly's take on being a reluctant meat-eater is amusing and well-drawn; there's a panel where there's a huge burger in the foreground and her teeth are almost comically about to rip into it. Lindner's story adds a whole new level of polish to her work, as demonstrated by her hilarious story about an elaborate break-up. Jennifer Hayden's story about her imaginary lusts and Becky Hawkins' clever take on food and long-distance relationships are also notable.

The fourth issue is much more interesting overall; its theme is female friendship and it touches on a wider range of issues. Hawkins talks about her enormous frustration with having a straight female friend who was uncomfortable with her being a lesbian, with a great page showing her getting bigger than her friend and letting loose all her feelings--which she did not actually do in real life. Anna Bas Backer depicts a night out for two best friends with a lovely line as they both deal with body dysmorphia and gender identity issues. Cliohdna Lyons' beautiful strip about Marilyn Monroe doing Ella Fitzgerald a career-boosting favor has a scribbly, animated quality that makes it jump off the page. There are a half-dozen more excellent stories in this issue, from Katie Fricas' Mark Beyer-esque story about two women hunting beards to Glynnis Fawkes' breezily-drawn story about a lifelong friendship with a charismatic woman from Russia, to Frakes' sweet story about becoming friends with her sister to Francesca Cassavetti's manifesto about rejecting her mother's negative view regarding women. Lindner herself has a great autobio story about unexpected connections from her past and the way memory plays tricks on us. Even the lesser strips in The Strumpet tend to be at least solid, and the variety of visual approaches tend to limit the repetitiveness that plagues many themed anthologies.

Puppyteeth #4, edited by Kevin Czapiewski. One of the most interesting developments in micropublishing over the past decade is the phenomenon of young publishers and certain artists associated with them attempting to get better in public. The best example of this is of course Kramer's Ergot, whose first two volumes showed editor Sammy Harkham getting his bearings, whose third volume showed promise and whose fourth volume had a huge impact on comics. Czapiewski's Czap Books is slowly but surely doing the same, seeking out young artists and nurturing their careers. Czap Books' flagship title is Puppyteeth, which has improved issue-to-issue. The fourth volume is certainly the most interesting and best-looking, and he was wise to pare down the number of contributors and instead provide a platform for longer, more interesting stories.

Puppyteeth #4, edited by Kevin Czapiewski. One of the most interesting developments in micropublishing over the past decade is the phenomenon of young publishers and certain artists associated with them attempting to get better in public. The best example of this is of course Kramer's Ergot, whose first two volumes showed editor Sammy Harkham getting his bearings, whose third volume showed promise and whose fourth volume had a huge impact on comics. Czapiewski's Czap Books is slowly but surely doing the same, seeking out young artists and nurturing their careers. Czap Books' flagship title is Puppyteeth, which has improved issue-to-issue. The fourth volume is certainly the most interesting and best-looking, and he was wise to pare down the number of contributors and instead provide a platform for longer, more interesting stories.

The linework and themes of Jenn Lisa's work, for example, are not unlike those of Tom Hart's with a splash of watercolors. It's a stripped-down and heartfelt narrative. Jess Wheelock's earthy and weird use of colors mimics a light show seen at a disco, only here it illustrates the strange relationship between a talking carousel horse and a waitress at an Applebee's. The use of color creates an emotional narrative that runs in parallel with the narrative created by the linework and text, commenting on and giving each version of the story a different perspective. It's the sort of thing that Dash Shaw does so well. For a couple of creators in the book, manga and anime are clear influences. Paula Almeida attempts a sort of emotionally dramatic action epic, though her "excerpt" of such a story borders on incoherence. More on-target is Laura Knetzger's story about a world-wide technology failure that leads her to retreat into the forest like San from Princess Mononoke, down to her wanting to confront the wolf gang howling outside her door. Jon Gott's photographs and newspaper clippings form a narrative about Cleveland that talks about progress, race, and paranoia; it's presented as interstitial material that slowly materializes into understanding. Czapiewski has edited an anthology that's in turns both entertaining and challenging.

Meanwhile... #1 & 2. John Anderson revived his late '90s comics anthology with one primary mission in mind: to give Gary Spencer Millidge an opportunity to finish his long-abandoned Strangehaven series. Another late '90s favorite, Strangehaven received Ignatz nominations and was well-liked for its mix of weirdness inspired by Twin Peaks and The Prisoner. Publishing with the small but ambitious UK concern Soaring Penguin Press, Anderson certainly has no shortage of confidence in the material, using the tag line "Introducing the New Golden Age of Comics." While there are some nice mainstream/genre comics to be found in these pages and they're presented with excellent production values, Meanwhile... isn't exactly a revolutionary publication. That said, Millidge's series is as weird and dreamy as ever. Much like the film Hot Fuzz!, "Strangehaven" pokes its head into British village life, unearthing secret societies, possible aliens, murder, romantic trysts, and towns that possibly have minds of their own. Rendered in his photorealistic style, Millidge takes advantage of color in the anthology to add further depth to his highly enjoyable story.

The other anchor strip, David Hine & Mark Stafford's note-perfect "The Bad Bad Place", feels like it could have appeared in 2000 A.D. The grotesque, cartoonish art tells the story of a different sort of British small town, this one about a new property development built on top of a long-abandoned site, complete with a mysterious and awful house that slowly drew in its population. It's a funny, creepy story that's an excellent complement to the drier "Strangehaven". The rest of the material is up and down. The translation of Yuko Rabbit's "10 Minutes", about a girl whose exit from a specific room could cause the end of gravity, is slow-moving but intriguing, with a light and naturalistic line. The other standout story in the first two issues was Krent Able's demented "Inc.", imagining a horrific world where savage cults have formed around abandoned business cultures. Able's grotesque level of detail is horrific and hilarious all at once, and it's the one entry in either issue that really pushes the envelope.

Music

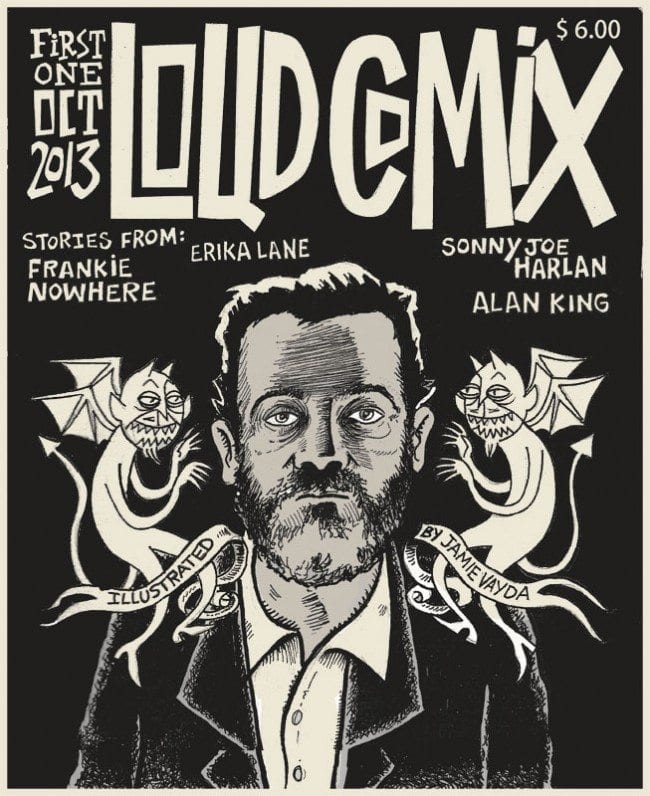

Loud Comix 1-4, edited by Erika Lane. This anthology attempts to capture the lurid, edgy, and dangerous aspects of being a musician, as each story is written by a practicing member of a punk or hardcore band. Every story is illustrated by Jamie Vayda, an artist whose work reminds me a little of Tim Lane's, only more cartoony. He's especially skilled at depicting the seedy, sleazy, and disreputable aspects of the rock 'n roll lifestyle and doesn't shy away from sex and violence, taking a visceral but whimsical visual approach. The first issue is by far the best, with the title settling into a familiar rhythm of over-the-top debauchery that quickly loses its shock value and starts to become repetitive. The first issue's "Mr. Breeze" (written by Sonny Joe Harlan) sets the pace for performers getting involved with the wrong sort of woman (a frequent theme). The Frankie Nowhere-written "The Rise of Billy Bloodlust" entertainingly fills the slot for drug-induced insanity, while Erika Lane's "Johnny Funhouse" settles into the niche for stories about weirdos and freaks. The only writer who rises above cheap thrills and delves a bit into the humanity of his subjects is Alan King, whose stories about crazy relatives and other lost souls is worthy of its own title. His work meshes especially well with Vayda's art, bringing out the best in the artist, including a touch of restraint.

As You Were 2-3, edited by Mitch Clem. If Loud Comix represents punk and music in general as a force for generalized debauchery and anarchy with a connecting thread to underground comics, then As You Were represents a modern, communitarian, zine-era version of punk that emphasizes commitment, identity and rejecting mainstream values in an entirely different manner. If the theme of Loud is "I don't give a fuck," then As You Were's overriding concern is sincerity. Indeed, many of the comics here are about being straight-edge, vegan, and feminist. Issue #2 is all about the experience of the mosh pit, both as a positive aspect of the experience that allows one free expression and an outlet for anger and energy, as well as a place used for gratuitous violence and/or sexual harassment/assault. A few creators in this issue bear special mention. Liz Prince's story about her annoyance with the sort of fan who spends an entire show documenting it with their phone is a familiar one, executed with a sort of scribbly rage. Editor Clem and artistic collaborator "Nation of Amanda" deal with his crippling social anxiety at a show in a manner that's raw and doesn't pretend to have a happy ending. Andy Warner and Rachel Dukes both provide visually evocative strips about the silliness and joy, respectively, of being in a mosh pit.

As You Were 2-3, edited by Mitch Clem. If Loud Comix represents punk and music in general as a force for generalized debauchery and anarchy with a connecting thread to underground comics, then As You Were represents a modern, communitarian, zine-era version of punk that emphasizes commitment, identity and rejecting mainstream values in an entirely different manner. If the theme of Loud is "I don't give a fuck," then As You Were's overriding concern is sincerity. Indeed, many of the comics here are about being straight-edge, vegan, and feminist. Issue #2 is all about the experience of the mosh pit, both as a positive aspect of the experience that allows one free expression and an outlet for anger and energy, as well as a place used for gratuitous violence and/or sexual harassment/assault. A few creators in this issue bear special mention. Liz Prince's story about her annoyance with the sort of fan who spends an entire show documenting it with their phone is a familiar one, executed with a sort of scribbly rage. Editor Clem and artistic collaborator "Nation of Amanda" deal with his crippling social anxiety at a show in a manner that's raw and doesn't pretend to have a happy ending. Andy Warner and Rachel Dukes both provide visually evocative strips about the silliness and joy, respectively, of being in a mosh pit.

The third issue's theme of "Big, Big Changes" directly tackles the notion of growing up and out of the scene, with a number of strips dealing with marriage and having children. Once again, Prince's strip about how her wardrobe (and to a degree, her identity) has evolved over the years is a highlight, but the best story is by Cathy G. Johnson. "A Happy Death" is about Johnson finding a kindred spirit in a fellow philosophy student, only to slowly realize that his cynicism was less about fighting things that she found unjust and boiled down to mere nihilism. While some of the strips tend to get repetitive in terms of the themes covered, and their earnestness can be a bit overbearing at times, the sheer enthusiasm of its creators and their varied approaches to storytelling (from crude scribbles to polished naturalism) makes this anthology series worth a look.

Broadsheets

Believed Behavior #1. This is a sampler anthology from a group of Chicago-area cartoonists. With just five artists and twelve total pages, it provides a brief look at the highly stylized and eye-catching aesthetics of each of these interesting cartoonists. Each artist has an aesthetic totally divorced from the others, which makes for a jarring but attention-grabbing read. Krystal DiFronzo's ode to nature is in turns beautiful, poetic and funny. Edie Fake's astonishing "Night Taps" fractures the image in each panel by presenting it as a window, with each panel presenting a new and frightening image about monstrous home invasion. Grant Reynolds' strip is all about personal transformation and gender fluidity, while Jeremy Tinder's cartoony strip is about a loss of identity taken to an absurd extreme. Andy Burkholder's comic presents a near stream-of-consciousness set of narrative captions with simple illustrations, detailing a non-neurotypical mind. What I like most about this anthology is that the artists involved seem to be really pushing themselves and are treating this collective as a place for their "A" material. Fake in particular is one of the top young talents in comics and demonstrates an ever-evolving sense of aesthetics and storytelling.

Smoke Signal #20, edited by Alex Spiro and Gabe Fowler. This is a collaboration between the publisher Nobrow and the quarterly broadsheet anthology published by the Brooklyn comic book store Desert Island. In many respects, Smoke Signal represents alt-comics' zeitgeist more than any other publication on this list. That's because their aim is to print stories ranging from the most established stars in comics (as evidenced by the Gary Panter/Charles Burns collaboration) to its most interesting creators at the height of their powers (Dash Shaw, Michael DeForge, Luke Pearson) to younger creators who show promise. The clean, colorful Nobrow aesthetic is in full effect here, from the Jon McNaught cover to the standout single-page strips by Bianca Bagnarelli.

Pearson's strip is especially interesting, as it features a kid who finds all sort of tiny, weird creatures and puts them in a box in an attempt to make them do something interesting. It's a funny bit of self-deprecation. Shaw and DeForge add some much-needed grit to the colorful proceedings, with DeForge's typical body comedy-horror and Shaw providing what seems to be a personal anecdote. There's a bit of Ben Marra's usual satirical ultra-violence as well as a number of illustrations typical of a Nobrow anthology. This issue of Smoke Signal is really more of an extended sampler than a true anthology, especially since there's little in the way of flow between strips. It's a nice appetizer presented in a way that flatters the material. The fact that it's a broadsheet rather than a traditional minicomic or book mitigates that "sampler" effect, because the huge size of each page encourages the reader to think of each page as a unit, rather than part of a greater whole. In that sense, this issue is a huge success, especially in terms of introducing the NoBrow aesthetic to new readers. The fact that Smoke Signal is free makes this issue a bit of well-curated free advertising, especially when the comics selected by Fowler look and read so much differently than the Nobrow selections.