1.

Seth's long in progress book, Clyde Fans, was released in full on April 30th of this year. Seth began this story in his floppy comic, Palookaville, all the way back in 1997. Upon completion, the story reveals itself to be anything but a hymn for the palookas of the world. In fact, it's quite at odds with them. No longer an affordable comic a 'palooka' might pick up casually and read on the toilet, we are now presented with a $55, 488 page behemoth.

How to approach a book with so much flop sweat swirling around it? I must first make it clear that I treat this book coarsely because I take it seriously. It is not the work of a beginner, but of a particular kind of cartooning master. Seth's skill and talent is not up for debate any longer. We must instead move on to the implication of what he is trying to say, the only way to engage with an artist of consequence.

When we open Clyde Fans, we will immediately see that the novel's title appears 11 times (including on the cover) before the story begins.

Three pages after this final introductory image, Seth's narrative begins.

In contrast, on a standard Oxford World Classic's edition of War and Peace, the title appears twice:

Yes, one work is a narrative that uses imagery (a comic), the other comprised simply of text (a novel) so the obvious defense (at this juncture) of Clyde Fans would be that the repetition of the title is essential to what the book communicates.

If that's true, there is quite a weight of expectation of what is expressed here. Earth shattering revelations should be in store. What happens after we read the words 'Clyde Fans' 11 times? Why was this choice made?

The TCJ Clyde Fans roundtable flailed wildly to triage the disparity between the works reputation/presentation and what it ultimately expressed. Expectation dampers are employed, assuring us to not believe our eyes: Clyde Fans might be too heavy to carry home from the book shop without some trouble, but it certainly doesn't see itself as an epic. It is, instead, 'a meditative visual poem,' albeit one on the level of William Blake. Jeet Heer asserts that Clyde Fans is 'anti-epic,' momentarily allowing the book some breathing room, then immediately finding it comparable to Samuel Beckett, Virginia Woolfe, Ezra Pound and Walt Whitman. So, not epic, but on the shelf next to the greatest visionary artist of all time and some principal modernists. Got it!

I don't think Seth and Clyde Fans has much in common with any of these authors or their works. Rather than assuage the disparity between the books expectations and its contents, these comparisons do further damage. I've read the book as a serial, and now again as a cinder block. It's clear that the decision to repeat the title is nothing but a statement unrelated to the drama of the story: 'just in case you don't get it, this is serious stuff.' We can be sure of this, as the actual drama of the book make the same claim, over and over again.

2.

I remember buying Palookaville #10, the first issue to serialize Clyde Fans, off the racks in 1998.

If we are going to address the story with the respect it asks (screams) for, we have to consider the contrast between how it was served to us in 1997 vs. now.

A female animator I admire once stated 'if I wanted to win a lot of grants and foundation prizes, I'd do what every successful animator does: a cartoon about an old man walking around all alone in his apartment.' This is the plot of the first 60+ pages of Clyde Fans, as Abe Matchcard reminisces about his life as an heir to the Clyde Fans dynasty. Now, when experienced serialized over a few floppy comics, it's worth a chuckle, right in line with the aesthetic the books title implies: a down and out former businessman gives us a cliche performance of defeat, tells some old funny salesman stories and we follow him around his living space. Scattered everywhere, we have the faux seedy theater tropes of Glengarry Glen Ross. The reader knows what they're supposed to feel on this terrain in the same way they know how to feel when they see the words 'Marlowe, PI' on a glass office door: comfortable with a story they already know the terrain of. Yes, yes...this salesman...regret...but also knowledge of, uh, the reality of capital! But also...'what's it all about' and, uh, the masculine world of...sales.

Genre. In the context of a floppy comic, this is a smooth 'sell' (as the characters of this book might woodenly joke, to perceived uproarious laughter by an audience of God knows who). Comics live and breathe genre, and an Ed Brubaker style hard luck story (with some greasy spoon 'truth' thrown in) drawn by Seth? Sign me up!

Of course, as the present day packaging and hyper important vibe corrects us, this is not genre. In fact, it's nothing less than truth revealed. Abe is telling us about what sales means, what his life in sales stood for. Yes, it's extremely borscht belt but of the uncomfortable borscht belt via Ontario variety, meaning: no laughs.

We are meant to see Abe as both as a fabulist and a sympathetic figure and a wise truth teller. Quite a high order to achieve such a portrayal. So how does Seth write Abe?

Is this passage above what sales, in reality, is about? We live in a moment in time formed by the same generation of salesmen as the ones Seth depicts in this book. One of them was Robert Welch, famous in one way as a candy manufacturer whose products (Junior Mints, etc) are as pleasingly designed as Abe's fictional Clyde Fans. Welch, however, is clearly more famous as the founder of The John Birch Society, the far right harbinger of our present decrepit political moment, in which conservatives of Welch’s stripe (in one way or another) have infected all forms of our government. Welch's view of life and business has been made mainstream, and we exist in his reality. Welch's attitude toward salesmen (summarized in Rick Perlstein's history of the conservative movement 'Before the Storm') is detailed in his text 'Road to Salesmanship' (1941): the importance of American salesmen, for Welch, rank them above doctors or lawyers. True salesmen induce citizens to buy things they can't afford, forcing self improvement by the private individual in order to obtain such things. That certainly sounds more like the reality of sales we all know in this world than Abe's fantasy mist: 'if you're really connecting with a customer, he'll remember you.'

Now, Welch's acrid views do not represent all of sales, all of commerce. But as Abe exists as some kind of business everyman, we have to ask: where where where are the cruel sides of sales and business? In Clyde Fans, they appear once, in a small, immediately forgotten incident (more on that later). On nearly every other page of Clyde Fans, we are instead treated to folksy feelings like this one:

Welch, while Abe was listening to the voices, was advocating for unfettered capital expansion, believing that government under progressive liberalism was 'a weapon of demagoguery and a perennial fraud.' That's a salesman.

Why should Clyde Fans address this side of business? Why can't we allow the book to be a fantasy of the pleasing, sleepy side of failed commerce, a sentimental journey through the regrets of forgotten manufacturers? Because Clyde Fans states that it is not about nostalgia, not about sentiment. This is a book about nothing less than reality itself.

3.

Clyde Fans concern with 'reality' is peppered into the text as a precocious student might insert the subject of a question into a reply, to make clear they are satisfying the requirement. The parameters Seth sets up are revealing. There is Abe's 'masculine' reality: out in the real world 'making sales' and telling stories with 'the people.' And there is his brother Simon's reality, cooped up in his private room in the Clyde Fans factory, (Abe eventually retires there as well, ultimately sharing with Simon an endorsement of this space as a superior reality to his own). Clyde Fans is, at its core, a debate over which reality is correct, which is real.

Readers will of course feel a pang of confusion over the obvious truth that is either obscured, omitted or simply not considered. To anyone with half a heart, neither of these situations approaches reality. The following Walter Benjamin passage, which I don't expect Seth or anyone to need to refute or even be aware of, must be employed in relation to Clyde Fans because in one sentence, the books plot is summarized and succinctly snuffed out:

"The private individual, who in the office has to deal with reality, needs the domestic interior to sustain him in his illusions."

Yes, obviously a cozy space where you control everything feels more alluring than anywhere else, we all flirt with that illusion---the important part is not to commit to it, to grasp the cheat of it, or, perhaps most powerfully, be aware of it. Clyde Fans, instead, mistakes illusion for earned wisdom.

This dissonance could be salvageable. We, the readers, might be able to find some 'reality' in Abe and Simon's debate if some laughter at this premise were inserted (again, make this legit Borscht Belt---it doesn't work without the self hatred). Through acknowledged confusion, and the recognition of stumbling around in the dark, we might find some poetry with these two, a noble attempt at understanding themselves. But there's no chuckling at or with either Simon or Abe on the thousands of panels we see of them, only solemn sitting in the pews for the reader, as our two men sermonize. We hold our tongues, wishing it was all parody.

4.

In one passage of Clyde Fans, Simon Matchcard---the younger and more introverted of the two Clyde Fans brothers, heirs to their fathers company---inspects his mother's chachka collections. In contrast to Simon's own passion for collecting novelty postcards, which is treated with an uncanny reverence, let's look at the words used to describe these items: 'remains of a short lived passion', 'cheap bisque figures', 'what was it about these four that so appealed?' , 'anyhow...'. Finally a 'Ukelele' [sic] above the bed forces Seth to repeat 'cheap' and remark that it was 'likely never played.' Simon's mothers collections bear the brunt of Seth’s complicated self criticism of his own collector/nostalgia obsessions. The author is aware of how his own sentimental preoccupations look, and offers ample self commentary in all his works. It’s telling, though, the treatment kitsch receives.

This passage from Seth's star making graphic novel, It's A Good Life if You Don't Weaken, has always bothered me. We observe a man cosplaying as an extra from a Edward G. Robinson film, scrutinizing the window display of a diner. The kitsch decoration items peak his ire. 'Did somebody actually make this beer cap doll/monstrosity?' [Yes]. 'Who put these plastic flowers in here? You can barely make out their colors under all that dust. The whole thing---it's kind of sweet and pathetic at the same time.' (Italics mine).

Why are Seth's affectations and interests, which are on display in this moment of scorn, worthy of earnest graphic novels, and other commercial aesthetic artifacts fit only for the dustbin? If this is a therapy of reigning in his own on-display wistful tendencies, the undertone of anger towards a certain kind of unacceptable visual culture is surging forth.

A panel from It's A Good Life, which expresses an affection for an orderly reality where you only see what comforts you, becomes prescient at this point:

Clyde Fans, over 20 years later, is an endless exploration of this panels bluntly stated desire: 'I want to live in a cardboard box.’

5.

'Those men understood the odds when they went on strike' says Abe, as he prepares to close his plant and his business because of union activity. I've never heard of a business actually shuttering due to worker agitation, but since Clyde Fans isn't actually about real business, let's accept it.

The sequence that follows is breathtaking.

Abe, after signing the paper work, wheels past the striking (now unemployed) workers. We've hardly seen anyone involved in the Clyde Fans company before besides Simon and Abe, and yet here they are. There are a lot of them!

Abe obliviously smokes a cigarette. We get that Seth is critical of this moment, but not critical enough to give any of the strikers a single line of dialogue. It's enough that he draws them with sad faces. Space within the gargantuan page count didn't allow for a scene, god forbid a name, to be thrown at any of them.

As Abe drives on, they are forgotten. What does Abe begin to think about directly after departing?

Why, an affair his father had, of course. Standard middlebrow fiction fare. Why does this book present itself as about 'sales' at all, when it's clearly not interested in anything so specific? Did we ever see Abe administering policy to his workers? Explaining the ins and outs of quality (or shoddy!) fan making to his staff? Do we know if the Clyde Fans company is a top of the line outfit or just a generic one? Was this a plant that offered its workers an attractive set of benefits, but they simply wanted more? Or where the working conditions at Clyde Fans abysmal, hence the strike? We are offered little more information than the following:

Also, air conditioning.

If the business details of Clyde Fans were left as hazy and general as the above panel, we could treat the work as fantasy. A scene of striking workers catapults it into some kind of statement about actual working conditions, but the workers are there as props: nothing, save Abe's earlier lament about the rise of air conditioning, justifying their sudden presence in the narrative.

This is not a book about sales, just the idea of sales, the idea that it would be nice to do a book about salesman. The notion that 'what is reality?' can also be dealt with in a book that is too blinkered to give coherent detail to its stated subject (salesmen, manufacturing) hints at how shoddy the final 'product' of the book (defining reality itself) will be.

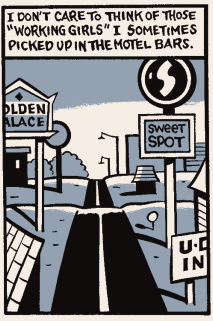

When Abe recalls the 'working girls' he would proposition, I wished for a book that was full on right wing, anti-labor, anti-worker, instead of a book that reveals its wrong headedness unintentionally. Yes, Abe is being criticized here, his misogyny and callousness on display. But his mindset is simpatico with the books conclusions: the men of business speak, justify, summarize, emote and offer self comfort, self validation. Everyone else is silent, literally without dialogue. It is clear who matters here, who is worth humanizing.

In Abe's recollection of the event, he says he closed the doors to Clyde Fans 'alone.'

We can't be sure what Seth means by this discrepancy, but the emotional logic of the book suggests that the above description of the event is the one to feel for. Abe matters most, he closed the shop alone, the throngs of nameless and voiceless other people are not there.

This is where the Clyde Fans Roundtable comparison of Seth to Blake is most in need of push back. Blake would, of course, find Clyde Fans abhorrent. Blake was a fierce (one of the fiercest) critic towards maltreatment of the poor by monied interest. It was Blake who wrote:

“Is this a holy thing to see, in a rich and fruitful land, babes reduced to misery, fed with cold and usurous hand?”

This is Seth:

6.

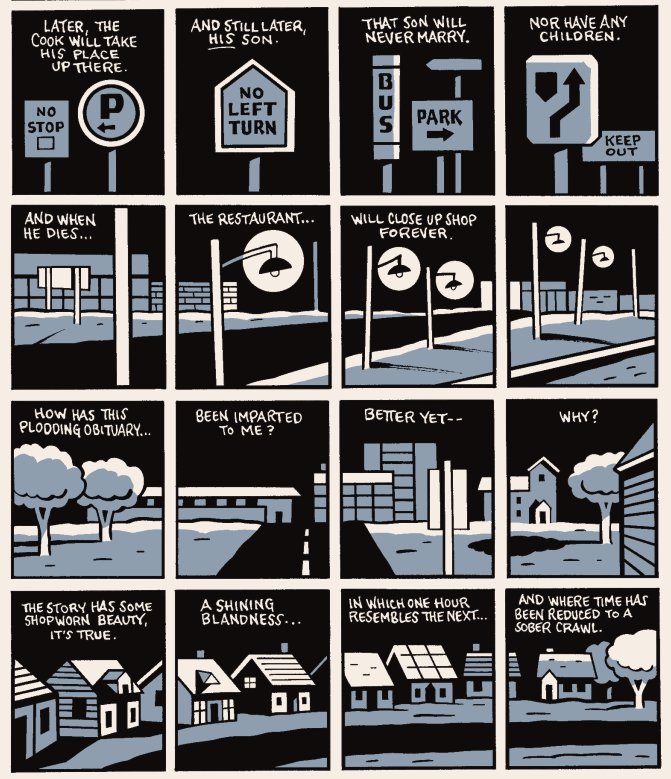

But, I'm falling for it again, mistakenly approaching this book as if it was about sales. I must remind myself: it's about reality. So let's explore the metaphysics revealed to us from on high.

Most of the books philosophy centers on Simon's experiences on his first (and only) sales excursion as a young man. Simon fails to close a single deal.

All the while, Abe's voice and image follow him, observing his every misstep as confirmation of Simon's true character.

Seth stresses, in every gesture Simon makes, the younger brothers' extreme effeteness, a dubious archetype to begin with. Simon is a caricature of a caricature. Seth needs to pull him into the specific with something resembling uniqueness. The pages and pages of failed sales attempts are the best (and most 'real') part of the book, because they offer nothing more than mundane circular rising tension and disappointed implosion. But 'a meditative visual poem' can't hang its hat on cyclical frustration. Instead, an epiphany must be inserted.

Simon, as his sales attempts evaporate, ventures out into nature and embraces a tree. He smiles, for the first time, but can't sustain it.

This moment happens towards the beginning of the book, and acts as a cliffhanger. What happened under this tree changed Simon forever, communicating a truth about the 'outside' world vs. living in seclusion. We are purposefully shielded from what, exactly, was learned until the books final page. We see Simon, throughout the books middle act, as an older man, grappling with the consequences of that fateful night.

Seth's storytelling of Simon's sales trip is superb: in those pages we experience the obvious foil of Simon vs. Abe wrung out for all it’s worth, exploited to an emotionally powerful degree. But the book abandons the charge and instead uses Simon's epiphany to sharpen the foils to an appropriately telegraphed degree.

'It never felt real out there' vs. Abe's stated understanding of the supremacy of 'men with real work to do.' (Just not these kind of men):

Of course, Abe's involvement in the world doesn't sustain him forever. The malaise of ruggedness pulls him into the orbit of Simon's worldview after all.

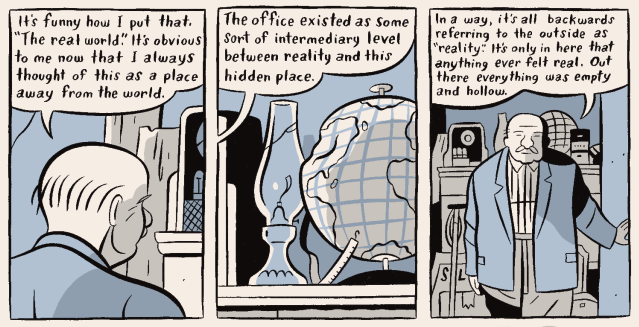

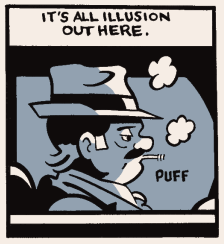

Later, he even mocks his perception of the outside as 'reality.'

So, for both brothers, the entire book hinges on that fateful night.

Seth returns us there, 236 pages after we left. His business trip a wash, Simon describes himself 'emptying out' and 'fading' into 'the solid world.'

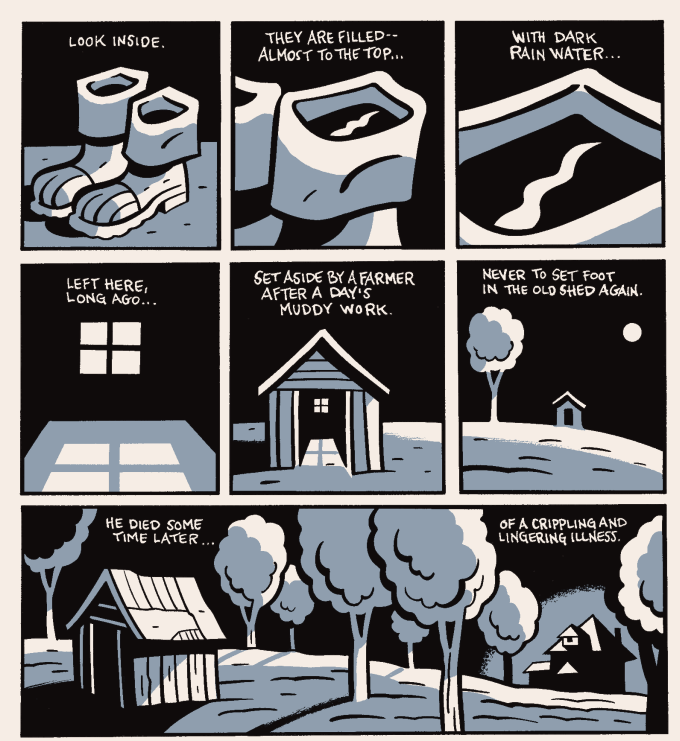

This 'solid' world reveals to him the core of all things, but, crucially, makes storybook assumptions about what goes on in these 'real' spaces.

Simon's view of the solidity is similar to how we were shown the strikers: assumptions are the core, the cliche of 'a days muddy work'.

We are even allowed to pick and choose a received idea of this salt of the earth man:

Simon is on an odyssey to become one with these solid spaces, but he never turns his narrow mind off, narrating these 'real' places to himself with hackneyed summaries.

As Simon lets the truth of black water 'sink in,' there is conveniently no human voice or face to contend with. Inanimate objects are enough for him to assume he's having a correspondence with what went on here.

As Simon lets the truth of black water 'sink in,' there is conveniently no human voice or face to contend with. Inanimate objects are enough for him to assume he's having a correspondence with what went on here.

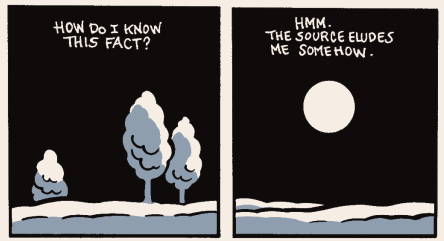

At one point, Simon questions his own assumptions...

...only to instantly resolve the conundrum with more self assurance.

The inference marathon continues:

'The story has some shopworn beauty' but who is telling it? Simon acts as if he's making a discovery. In fact, he is telling a story of himself to himself, in the same way Seth tells a story about visual culture to an audience of his own psyche.

This journey through abandoned spaces, 'learning' from them, reaches a crescendo:

After unsuccessfully trying to sell fans, Simon's odyssey of looking at broken down buildings and tying a romantic bow on top of them reveals to him a deeper romantic bow:

This, Simon concludes, is the path he must pursue as a person.

Simon’s failure to connect with his fellow man forces him (no middle ground is explored, no space for anything but binary choices in 488 pages) to find not just beauty in humanity's absence, but a way of life to emulate. Isolation is not a note to play, but instead the entire piano. The puzzle solved, Simon enjoys his first sustained smile...

...and, more importantly, a triumphant meeting with Abe upon returning. This is the real Simon now.

He spends the rest of his life in his private room in the Clyde Fans building, biding his time there collecting novelty postcards and other nostalgia items, including Blackface dolls, which silently confront him:

Like the inanimate buildings Simon confronts, his collectable items speak only through the voice of his own already made up mind. Simon does not interact with anything he cannot insert the dialogue of. The dolls and postcards exist largely as a meta self criticism of Seth himself (a callback to his kitsch self torture), his back and forth questioning of his nostalgia persona, but they also serve as the sentence Simon must deal with in wild eyed choice for self confinement. Seth, in fact, shows that Simon does have regrets. His euphoric moment did not last:

But as with Abe's immediate focus on a familial affair after speeding past the striking workers, Simon's plight and quest for 'reality' ignores how he can choose to retire to this room and choose to regret it. These men have something to do with Simon being able to sit in his room for as long as he likes:

Clyde Fans' workers, the former inhabitants of the abandoned houses Simon surveyed, those who are the victims of the hateful imagery grafted onto Simon's dolls: all have no voice in Simon's cosmos, even though his self affirmation hinges on reaction to all of them. Clyde Fans oscillates between critiquing and wallowing in the fallout of Simon's aloneness. The book ends on this image, with Simon in full thrall of his choice:

Regrets are on the way, but the book seems to state that one should commit to this feeling, this endorsement of a human life as on par with an abandoned building.

7.

Or does it? We must return to this above panel. Clyde Fans offers a confrontation with reality from an artist whose stated desire is to live in a confined---and most importantly, safe---cardboard box. Simon's journey is Seth's.

Chronologically, this is the last image we see of Simon. Clyde Fans is a partial rejection/partial embrace of his choice. But both the celebration and condemnation of Simon have been illustrated only with tools from inside the cardboard box. For a work of pure, unadulterated fantasy, this might have been transcendent. A vision of life so deeply felt and believed by one voice that nothing more was needed than the artist's self-circulating reality. True surrealism operates on this principal.

Instead, Seth offers a compromise: a dialogue, but with his own voice on both sides. Clyde Fans is an expression of Seth's mind, which would be thrilling if only it affirmed its stated love of the cardboard box in jubilant strokes. Simon says he 'awoke sometime later' but Clyde Fans lacks the voice---and refuses to search for articulation---to express what could be discovered after that awakening. To be clear, I don't mean simple redemption (which the book hints at anyway) but rather awareness of the books own implications. A celebration of the ridiculousness of ‘I used to like to get into cardboard boxes and close them up behind me’ made into a life choice would be something, but Clyde Fans instead offers a tortured sigh.

As seen with Simon's response to his mothers knickknacks or Abe's attitude to his employee's, Clyde Fans agrees with, perhaps unawarely, Simon's narrowness. The book, and Seth's art, is closed off from the world, but not gleefully and proudly. Rather, it is on the defense. And the chosen form of this defense operates with the books theme as its primary cudgel: mental isolation, imbedding within its pages bafflement towards any possible attack.

I look forward to the next book. There, I hope to see Seth's conviction and skill crystalized into the 'beyond reality' metaphysical fantasy epic he sketches out here.