It’s 2006 and I’m a recent School of the Art Institute of Chicago grad. I’m working as a dog walker, and will be for years to come. Somehow, I learn about a show called Masters of American Comics. It’s not coming to Chicago, but it’s opening at the Milwaukee Art Museum, about an hour away. I get in the car and go. I’ve recently begun drawing comics, but have never taken a cartooning class. This will be the first time I’ve seen original comics pages by professional artists.

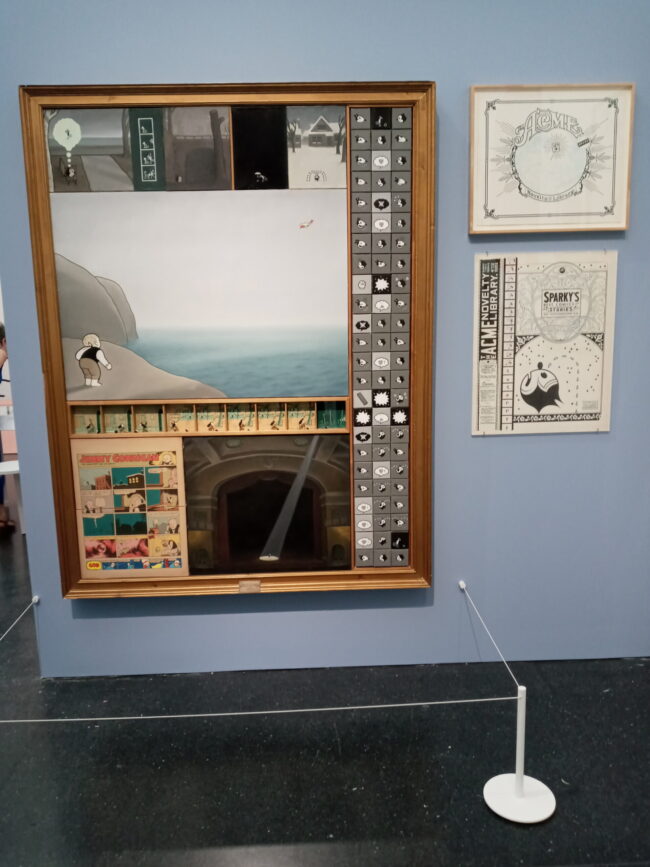

The exhibit is organized chronologically, and I marvel at the formal experimentation of early newspaper strips by E.C Segar, George Herriman and Lyonel Feininger. I thrill at a Devil Dinosaur spread by Jack Kirby. I’m perplexed by a sequence from Gary Panter’s Jimbo. His work is looser than the other artists in the exhibit, and his narrative approach seems less linear than artists like Art Spiegelman or Chris Ware. Nevertheless, it stays with me; lights me up.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that this exhibit taught me how to cartoon. It demystified the materials and techniques used to draw and reproduce the work that I loved. The fact that no women and only one POC artist were represented as “Masters” rankled, but I’d gained an invaluable insight into how the sausage was made, and for better or worse, it enabled me to make some myself. That democratization is the great good of civic institutions like libraries and museums.

Cartoonists are not used to institutional representation. We tend to feel most comfortable operating under the radar. That’s the devil’s bargain of cartooning. There’s no money in underground comics but, conversely, there are no rules. We can say whatever the fuck we want. Comics are cheap to make. The barrier to entry is unbelievably low and we like it that way. Cartoonists tend to be contrarians, and I think many of us feel ambivalent about the trend towards “comics as art” or “comics as literature” that’s been gaining momentum since the 1970s, in spite of also recognizing that our medium deserves a far better infrastructure, more study, and more respect.

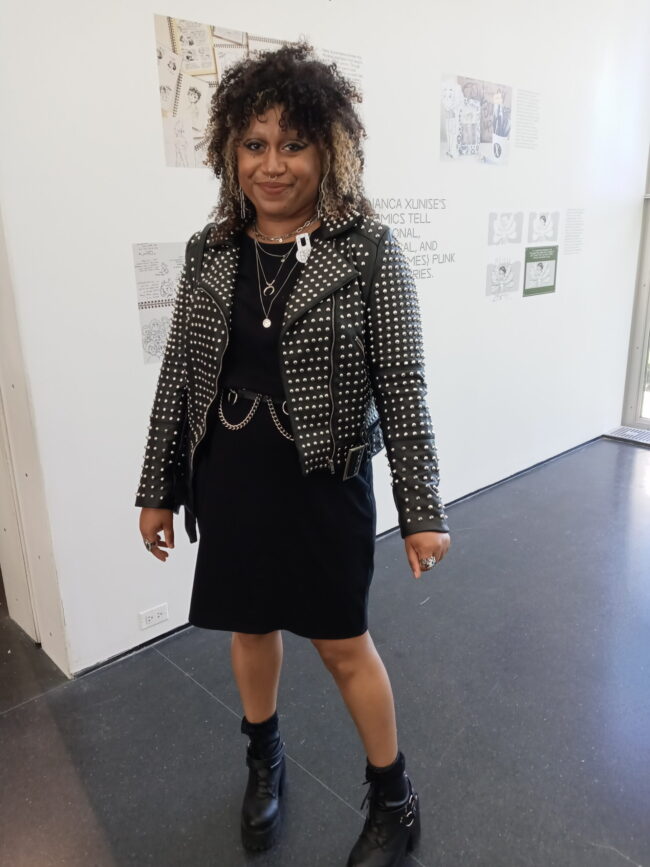

Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, seeks to rectify the gatekeeping missteps of the past by centering women and POC artists. The exhibit was rolled out over two days, with a virtual opening on June 7th and member walk-throughs and an artist’s reception on Friday the 8th. Dan Nadel [NOTE: a former editor of this site], who co-curated the exhibit, describes how it came about:

Michael Darling, the now former chief curator of the MCA, was aware of the comics tradition in Chicago, and felt a show based around the contemporary era of comics in the city would be a good fit for what’s become a tradition at the museum: every other summer the MCA mounts a show that brings “art-adjacent” subjects like fashion and music into the contemporary art zone. But he also knew that he didn’t have the expertise to do the show. He called me up in December of 2019 and asked if I wanted to curate it, and we started talking seriously in January of 2020. The show was almost entirely conceived and executed during the pandemic.

I am not an impartial observer. I have a small amount of work in the exhibit, and I consider Dan a mentor. As the mind behind the now-defunct PictureBox Inc, he published some of the funniest, weirdest, most boundary-pushing books to exist in the medium. In his second life as a curator, with exhibits like What Nerve! Alternative Figures in American Art, 1960 to the Present and Kings & Queens: Pinball, Imagists and Chicago, he preached the gospel of influential art collectives like Fort Thunder and the Hairy Who all over the world.

At the virtual opening, Dan mentioned that because of a lack of institutional support, “cartoonists are the historians of this medium.” I’d never thought of it in those terms but I was struck by the truth of that statement. It’s true for the medium writ large, but even more so for marginalized artists.

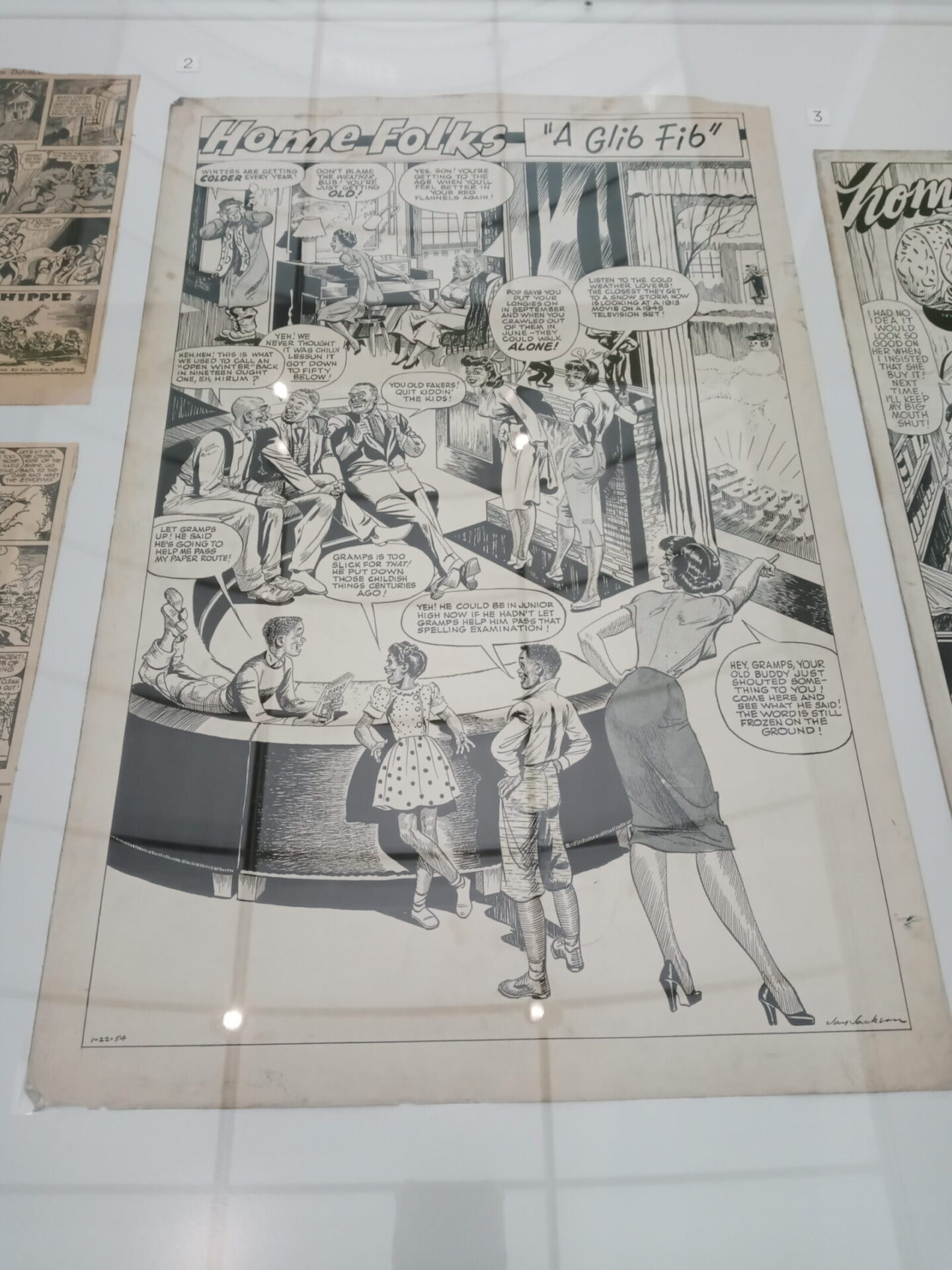

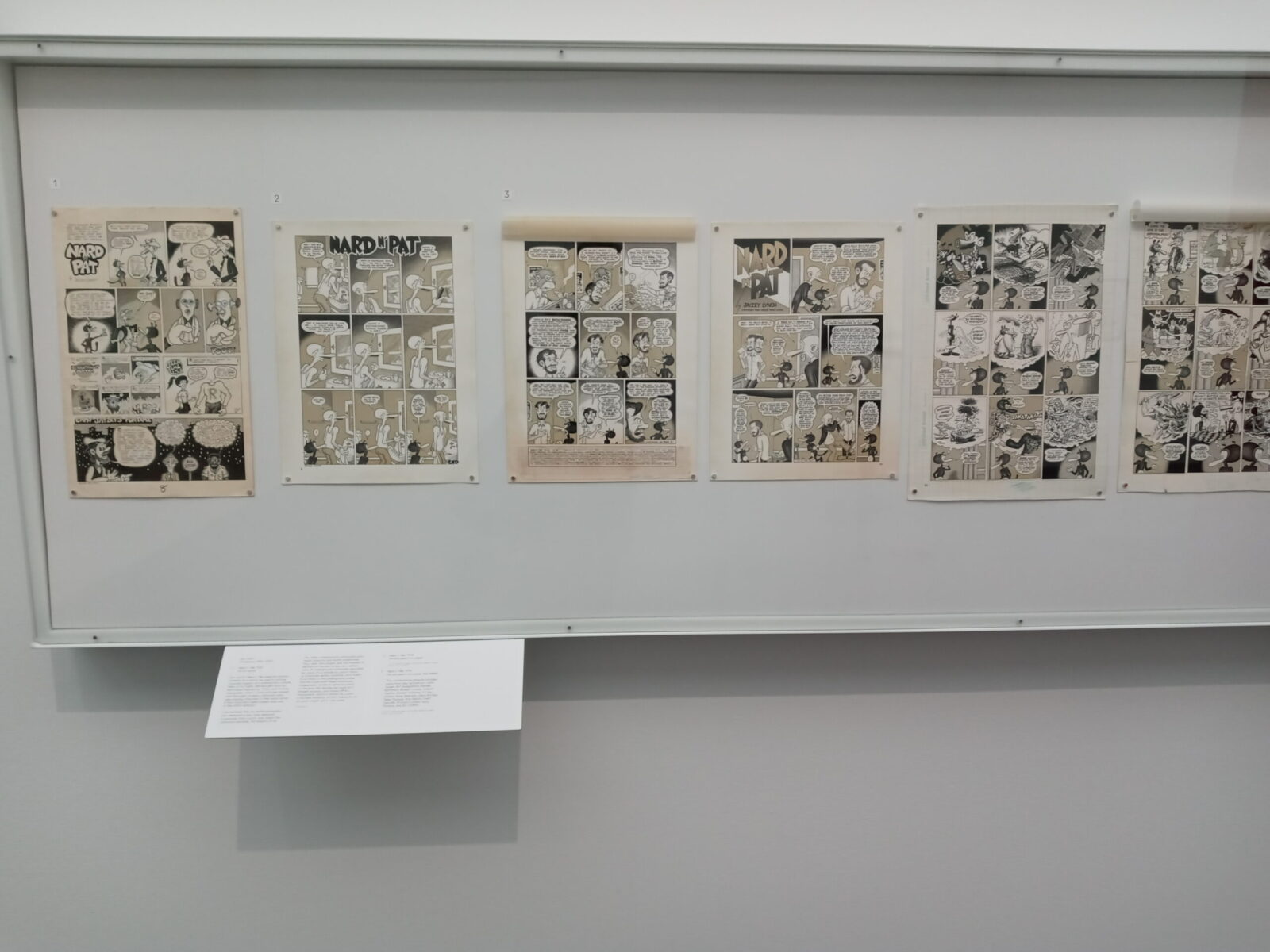

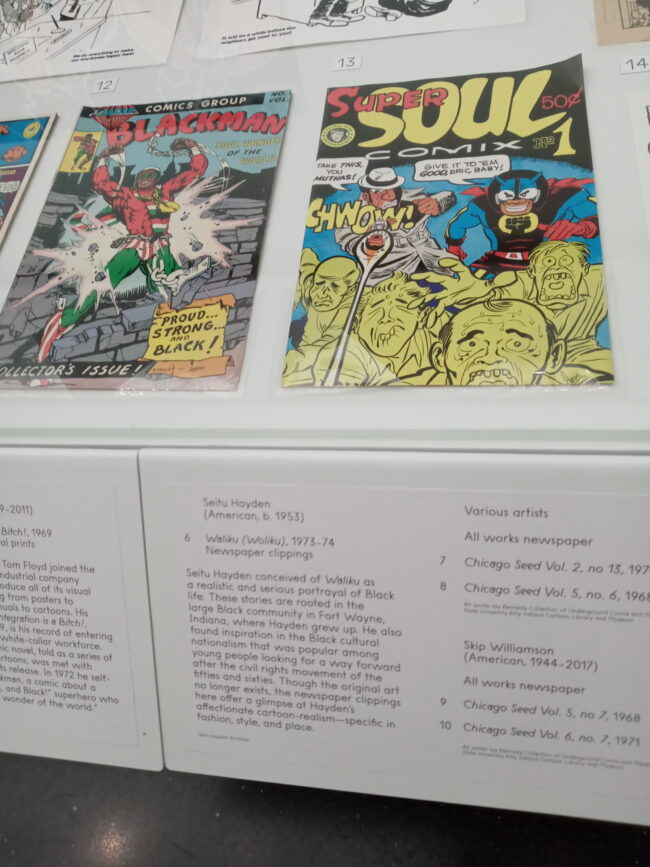

Chicago, like most major American cities, had a Black newspaper, The Chicago Defender, founded in 1905 by Robert Sengstacke Abbott. Over the next century, the Defender published dozens of Black cartoonists, many of them criminally overlooked. Cartoonist and scholar Tim Jackson, himself a Defender artist, published the 2016 book Pioneering Cartoonists of Color, a landmark work that helped to bring other Defender artists like Jackie Ormes, the first African American woman to work professionally as a cartoonist, and Jay Jackson, who reinvented the long-running strip Bungleton Green, into the comics-historical conversation. Adding to the conversation is the catalog It’s Life As I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940-1980, edited by Nadel in conjunction with Chicago Comics.

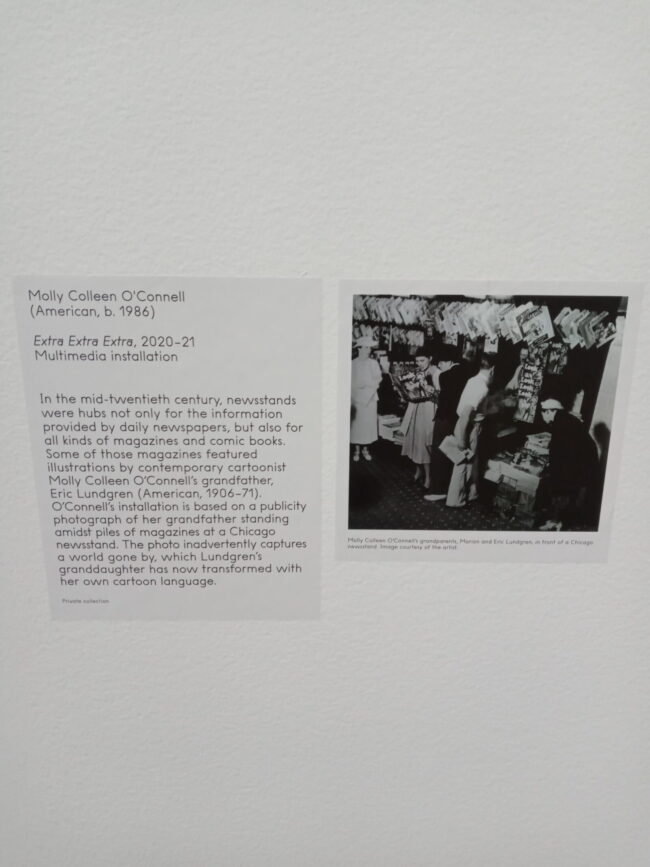

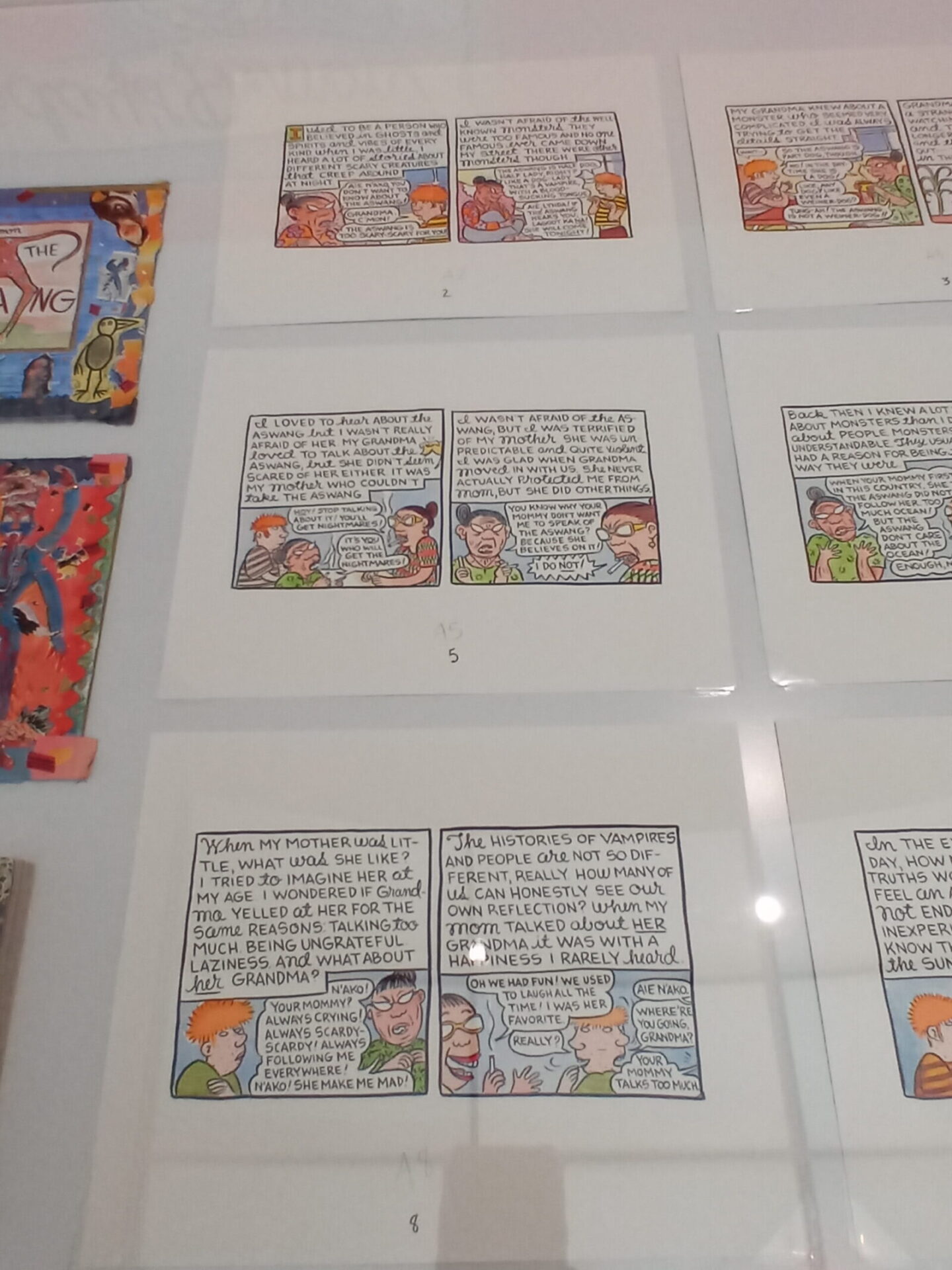

A handful of the artists featured in both books are featured in the exhibit, as is the blue chip painter Kerry James Marshall, whose project Rythm Mastr features characters based on discarded toys he’s found around the city. Not surprisingly, other fine artist/cartoonists are featured, including Edie Fake and Jessica Campbell, both represented by the local gallery Western Exhibitions, and Molly Colleen O’Connell, whose tribute to her grandfather, a pulp magazine cover artist, is a visual fulcrum point.

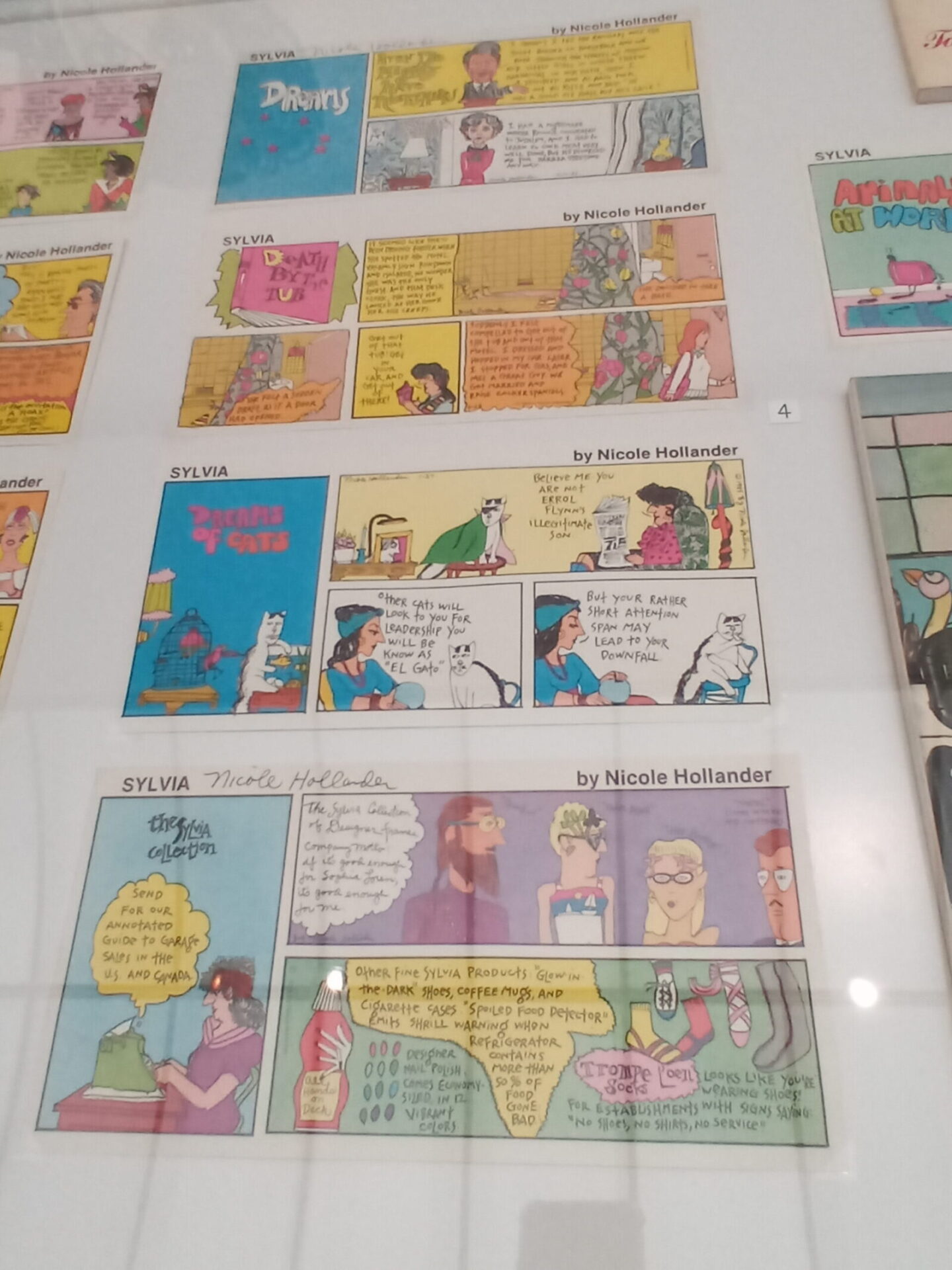

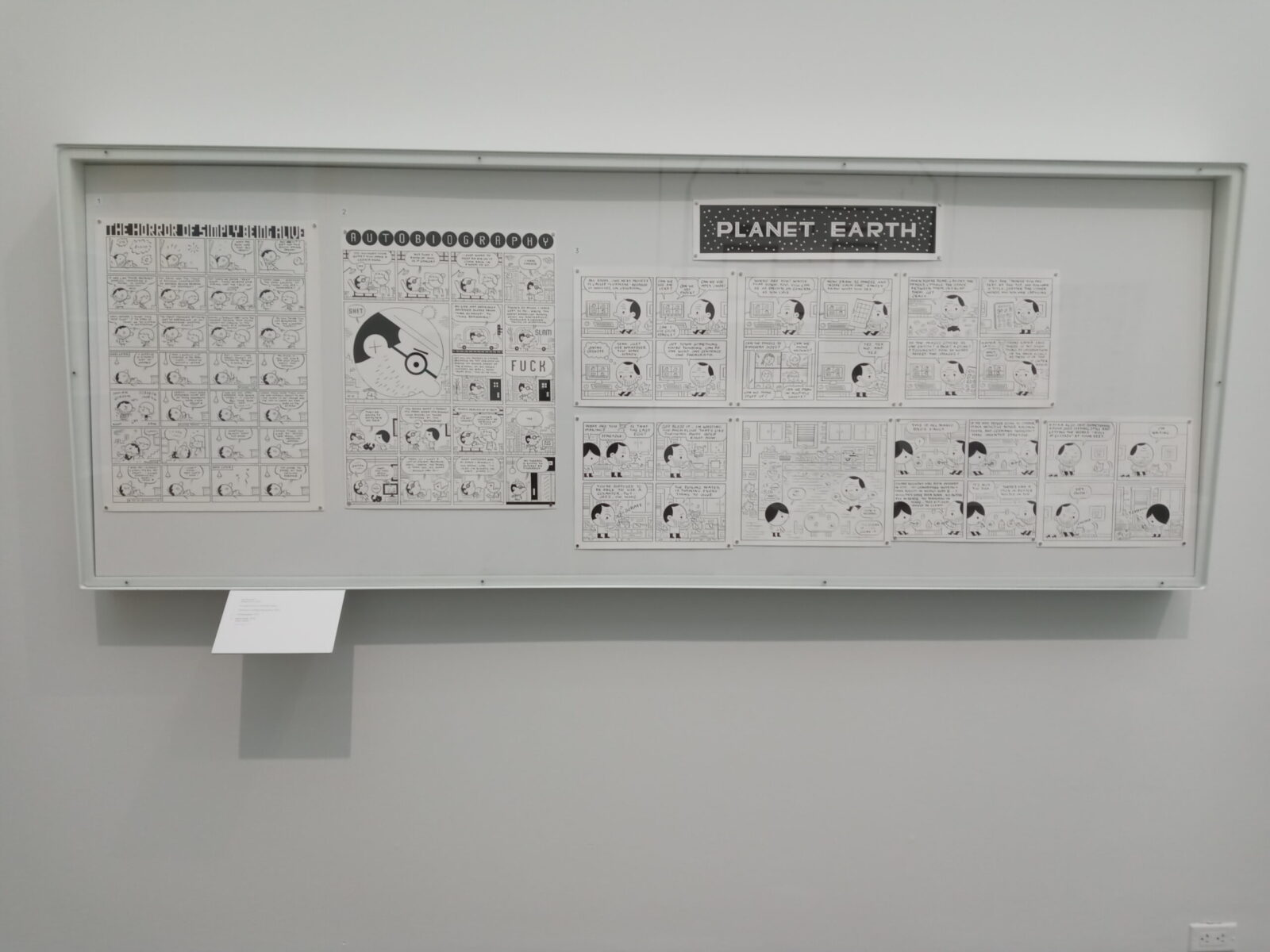

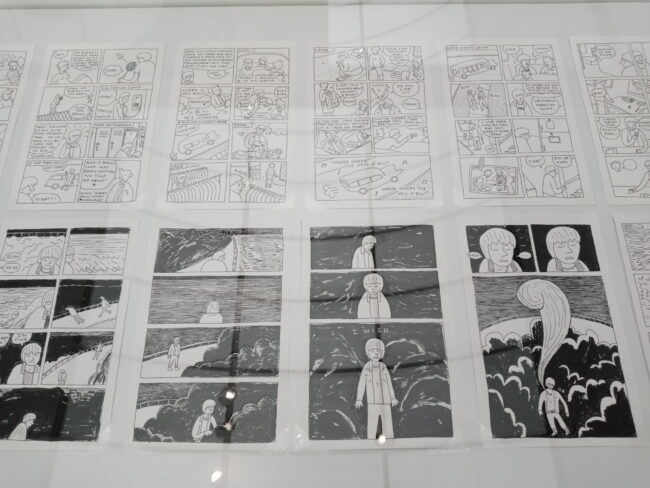

As one would expect, the exhibit moves chronologically, from the early newspaper strips through the underground era. Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson are well-represented, and I was excited to see an issue of Chicago Seed, an influential underground paper that published their work, in a display case. From there we visit the heyday of the free weekly, headlined by Chris Ware, Lynda Barry, Nicole Hollander, John Porcellino, Ivan Brunetti and Dan Clowes.

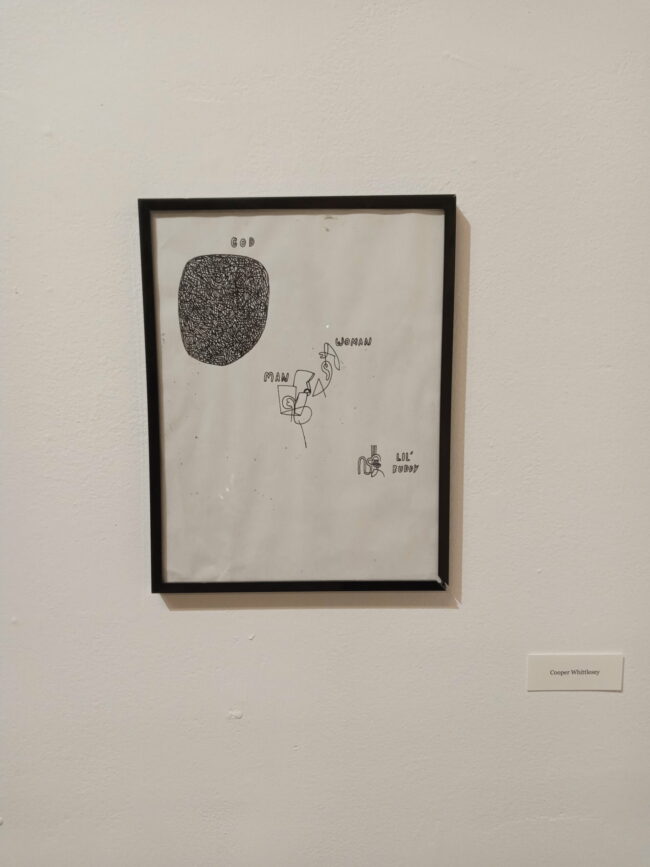

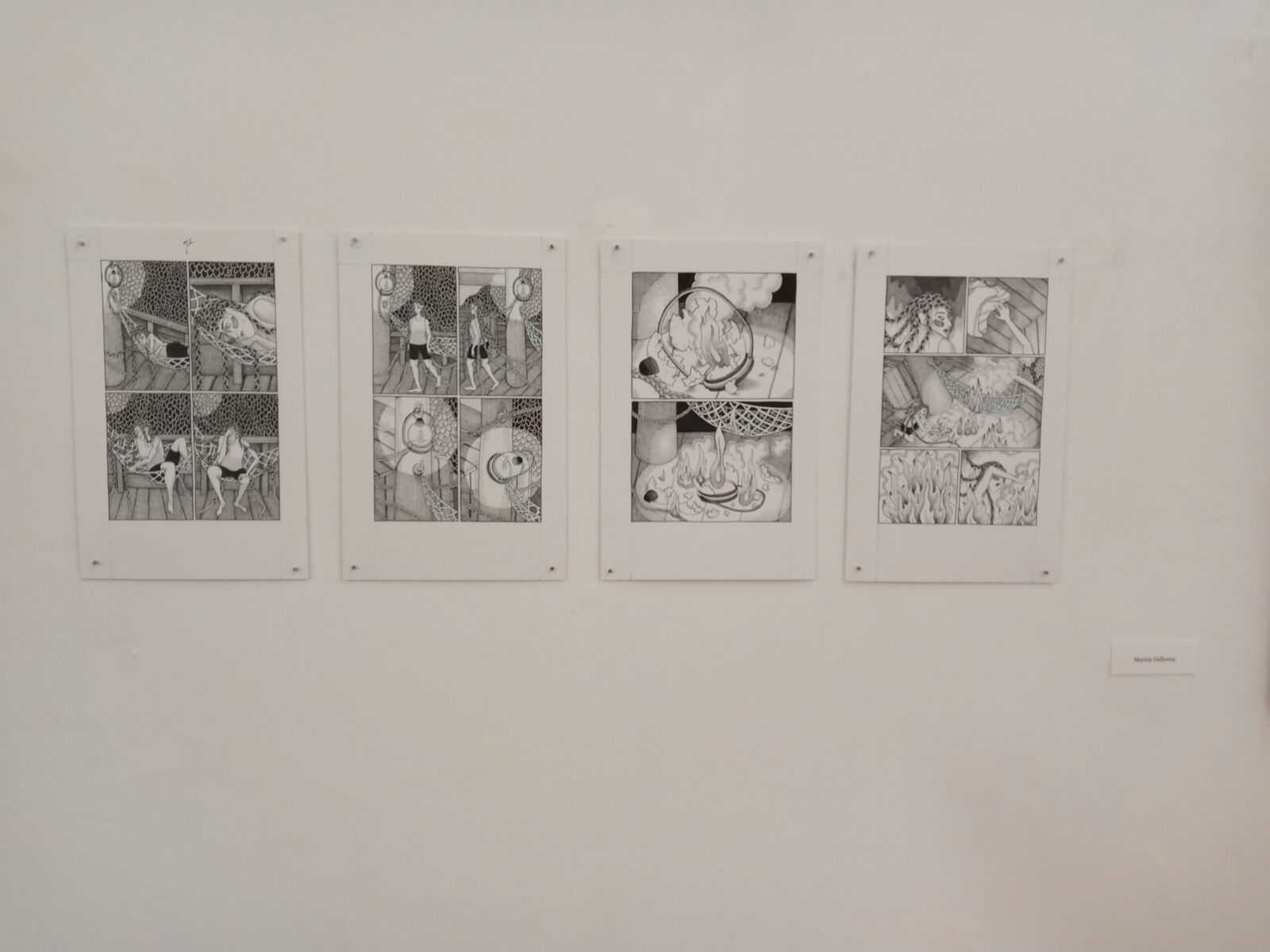

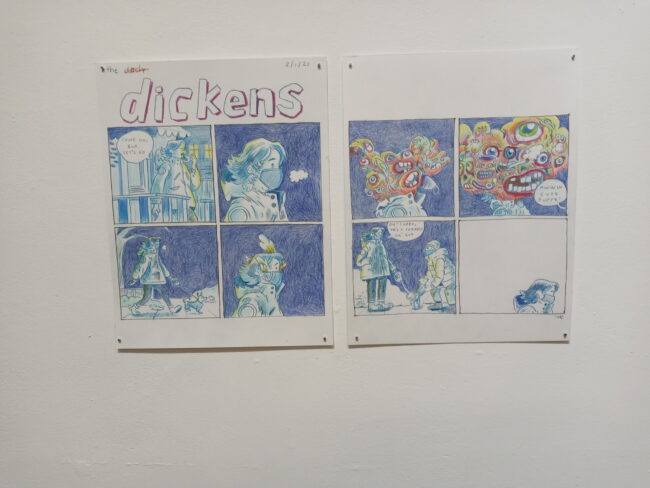

The exhibit concludes with a strong and diverse showing of younger and emerging artists. Cut-outs in the walls give the viewer a direct sightline from the beginning to the end of the exhibit, and provide a visual metaphor for the line of influence running from past to present.

When I asked Dan how he selected the artists, he responded that:

Every show has a different set of goals. For this one the two major goals were: (a) telling a diverse and inclusive story about Chicago comics with the goal of celebrating the city’s cartoonists and (b) making a show that could function in a contemporary art space. The two inform each other. I also very much hope that the show opens up further areas of research. I think there are books and essays to be written, and focused shows to be done about lots of people included (and not included) in this show. I want more research and more institutional muscle for that research. So, first I worked up a very long list of cartoonists I felt represented the history of comics in Chicago. This list was determined by the following factors (I might be forgetting some, but here goes):

-Simply put: It was important to me that the show reflect the ethnic, racial, sexual, and gender identity diversity of the city itself.

-Then: Cartoonists who work entirely on their own ideas/strips/comics free of any IP restrictions.

-Cartoonists who made or debuted mature narrative comics in the Chicago area for years. This meant that I disallowed artists who left Chicago after high school, say, or my beloved Hairy Who, who made artists’ books via a comic book grid, but not narratives.

-Then there’s the challenge of what comics are in the context of a large contemporary space (as opposed to study rooms or works-on-paper-specific galleries): small pieces of paper and books. Thus, one sheet by any artist isn’t going to register to a viewer. Each artist needed multiple sheets or a single larger project to register to a viewer. So, for example, I showed Jessica Campbell’s wall works because they’re part of her cartooning sensibility, and Edie Fake’s drawings because they cover themes implicit in his comic book work. I am very lucky to have worked with Thomas Kelley of the architecture firm Norman Kelley – he designed the show in a sensitive, beautiful way that met the needs of artist and viewer alike.

-Then choosing a handful of standout cartoonists for monographic sections in the show. These sections allow deeper dives into a cartoonists’ ideas and sensibility. These are cartoonists who have had an outsized impact, via their own work, teaching, or publishing.

-Then, understanding that MCA viewers may not be used to comics in a museum context, I decided to arrange it chronologically so that viewers could latch on to decades in the city itself. This meant that I had to limit the amount of cartoonists within each decade for simple reasons of space and coherence. And, again, I got to work with the utterly superb interpretives and education teams at the MCA to make sure it all actually made sense.

-Then I worked to find the right mix of cartoonists whose work was different enough in scale, texture, color, subject, and meaning to sustain the viewer’s attention over 10,000 square feet. In all, that meant 41 cartoonists represented by nearly 400 objects. It also meant that each section of the show could be easily expanded. Everyone has a favorite who was left out.

In other words, this show is not an attempt at defining a canon. It’s about telling an expansive story in a particular kind of space, right now.

A handful of artists who were initially slated to participate were cut from the show in the midst of the pandemic. This came as a blow to the artists, some of whom are professors. Unfortunately, the metrics of success in comics are different from those typically recognized by art school administrators. Participating in a museum exhibit can mean the difference between getting a raise or being passed over for merit-based pay. Nadel said:

As you know, the pandemic had an enormous impact on all arts organizations. In the case of this show, we faced budget cuts that meant the MCA had to shrink the footprint of the exhibition significantly, as well as the amount of wall and floor vitrines we could produce. In short, we had to cut a lot of art when we were well into the planning of the show. In order to make the show fit into the smaller space(s) and still function as a legible exhibition it was determined that there had to be fewer artists. This was the worst outcome of the show in a year of terrible outcomes for art. It was also out of my control. The choices had nothing to do with the quality of anyone’s artwork. It was about maintaining a balance of scale and material in the show, as well as, quite frankly, what could be shipped and/or shown with the displays we could make. I was, I hope, transparent about it with the affected artists, but I also didn’t intend for it to be a public matter, as I would guess it’s even more painful for them than it is for me. This was a very, very difficult show to pull off in an extraordinarily difficult time in all of our lives.

Chicago’s relative affordability, its history as a publishing hub and its emphasis on substance over style has attracted cartoonists since the turn of the 20th century. The warmth of the community has, for the most part, kept them here.

Community members immediately stepped in to fill in the gaps in Chicago Comics. An exhibition curated by cartoonists Iona Fox and Kevin Huizenga at a DIY gallery space provisionally called Gridsport featured the work of a handful of the artists who were cut from the MCA show. Gridsport also recently hosted the 15th installment of Zine Not Dead, a quarterly performative comics reading hosted by Matt Davis, owner of Perfectly Acceptable Press, and Brad Rohloff, of Bred Press. It’s almost impossible to overstate the importance of Zine Not Dead and its predecessor Brain Frame, hosted by Sir Lyra Hill, in fostering a sense of community among Chicago’s cartoonists.

Chicago: Where Comics Came to Life (1880-1960) at the Chicago Cultural Center, curated by Chris Ware (cartoonists ARE the best historians of the comics medium!), highlights the artists who prefigured the underground comix boom of the 1960s. In conjunction with that exhibit, Joe Tallarico, comics editor at Lumpen Magazine, curated Future Forward at Buddy Chicago, a retail space in the museum showcasing work by contemporary cartoonists, featuring Jeremy Tinder, David Alvarado, Chloë Perkis and others.

I teach cartooning at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which, like most art institutions, has been reckoning in the midst of the pandemic with its complicity in structural racism, and reimagining its function in the community. As a professor, I feel an obligation to be real with my students about the economic realities of being a working artist, so I asked Dan if he thinks the pandemic has permanently altered the way art is collected and shown. According to him:

It really depends on what you mean here - artists, visitors, museums, galleries, collectors-- all different. This is the subject of symposia and innumerable conversations. Here’s what I know: Museums are in fiscal crises that will impact scheduling, collecting, and programming for many years. And it’s impacted everyone in museums, as human beings, in a profound way.

A preparator at the MCA told me that there’s been a recent movement for more equity at the museum. A collective made up of current and former MCA employees called MCAccountable has been successful in campaigning for better pay for employees.

No museum exhibit is exhaustive. Chicago Comics is a wonderful jumping-off point for “civilians” unfamiliar with the history and possibilities of the comics medium. But it will introduce even grizzled comix veterans to new artists and well-known favorites, as well as more obscure, hard-to-find works. You will come away from it with a deeper understanding of the way comics are made, and a much greater understanding of who has been making them for decades in this city.

I thought some creative visualization might be a welcome antidote to my own gloomy prognosticating, so I asked Dan to imagine his dream museum. I’ll leave you with his response:

Ha, I think I know too much about museums to really fantasize... and full caveat, this is just how I feel this morning, July 2, 2021: I’d love to see a museum dedicated to works on paper from the 20th and 21st century. Just drawing, from E. Simms Campbell to Agnes Martin to Joseph Beuys to Nancy Grossman to Carroll Dunham to Mary Blair to Bill Everett to Xylor Jane to Kerry James Marshall to C.F. It would have exhibitions but it would also function as an archive and study center. It would be free and open to all. Operating... (taking seriously the idea that there are unlimited funds here, so no need for fundraising or any donors) artists and scholars would form a paid advisory group; no advance degrees (or actually, any degree after high school) would be required. Curators would dedicate their time to research, the registrar, exhibition management, and installation teams would decide how and what is feasible within the building itself, the education team would hold classes in the space and collaborate with communities, and the interpretives team would work with everyone to make sure the shows were both up to scholarly standards and accessible to viewers. Museum guards would also be docents. Oh, and everyone would be paid equally: about $200,000/year each.