Dr. Milton Thomas Inge — M. Thomas Inge, as he was known professionally, or Tom to everybody who knew him — did as much as anyone to make comics a distinct object of study in academia. He played a key role in the story of how comics studies became a field, as opposed to a scattering of isolated projects. As author, editor, anthologist, bibliographer, organizer and teacher, Inge seemed to love comics studies into being — not alone, of course, as he would have admitted, but with a gift for companionable collaboration. His death on May 15, and the long career story that has come back so vividly by way of remembrance and tribute — these are reminders of the humanness and contingency of scholarship, and the way one generous and welcoming scholar can make a difference.

Dr. Milton Thomas Inge — M. Thomas Inge, as he was known professionally, or Tom to everybody who knew him — did as much as anyone to make comics a distinct object of study in academia. He played a key role in the story of how comics studies became a field, as opposed to a scattering of isolated projects. As author, editor, anthologist, bibliographer, organizer and teacher, Inge seemed to love comics studies into being — not alone, of course, as he would have admitted, but with a gift for companionable collaboration. His death on May 15, and the long career story that has come back so vividly by way of remembrance and tribute — these are reminders of the humanness and contingency of scholarship, and the way one generous and welcoming scholar can make a difference.

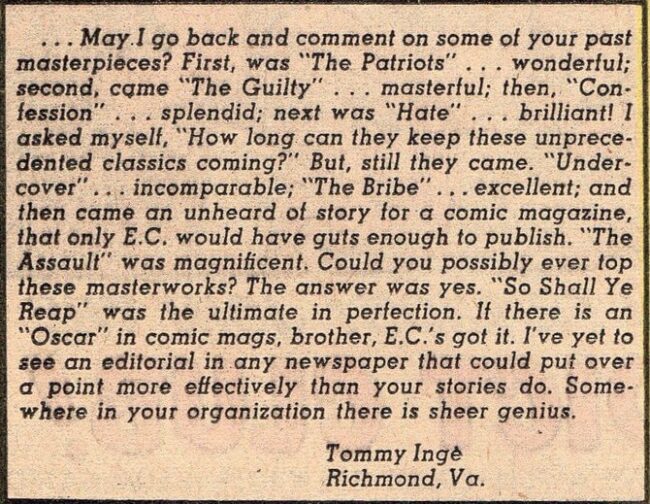

Early on, Inge (born in Newport News, Virginia, on March 18, 1936) nursed dreams of becoming a cartoonist. He loved comics as a child and credited them with teaching him how to read. In 1947, at age 11, he encountered Coulton Waugh’s book The Comics, which he recalled as ushering him into the comics world (he would supervise a reissue of Waugh’s book in 1991). As a teen, he became an EC Fan-Addict and contributed to Bhob Stewart’s EC Fan Bulletin; as “Tommy Inge,” he had a letter published in EC’s Shock SuspenStories in 1954. This foreshadowed his later work in fanzines and prozines: The Menomonee Falls Gazette, Comics Buyer’s Guide, and many others. Inge was always in touch with the world of comics collectors; starting in 1975, he contributed an annually updated “Chronology” to The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide. However, at Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia, in the mid-1950s, he chose to study English and Spanish. He would sometimes refer to himself, years later, as a “failed” cartoonist. After earning his bachelor’s in 1959, he went on to Vanderbilt University (where another pioneering comics scholar, Don Ault, would one day teach) and earned his master’s in 1960, then his Ph.D. in 1964.

After Vanderbilt, Inge pursued not only Southern literature and culture and American studies generally, but also, crucially, the study of popular culture, humor and comics. He made such vital contributions to those fields that it is fair to wonder whether they would have become the fields they are without him. Certainly, he opened the gates of academia to an outpouring of comics scholarship that by the 1990s helped make comics studies into a distinct area. In short, Inge changed the professional landscape. In the process, he became both a father figure and constant learner among several generations of scholars who looked up to him with a certain awe.

In the mid-1960s, as a newly minted PhD, Inge took a job at Michigan State University in what was then the Department of American Thought and Language (1964-1969). MSU would become another important school in comics studies (now known for the MSU Libraries Comic Art Collection). While at MSU, Inge taught the first accredited university course on American humor, and in it he included comics — a gutsy move in 1968. From MSU, Inge went to the then-recently founded Virginia Commonwealth University, where he taught from 1969 to 1980 (becoming Chair of English in 1974). He ended up donating many books, papers and original works of comics art to the VCU Libraries, where a special collection was established in his name. Inge then served as Chair of English at Clemson University for four years (1980-1984), during which time he also worked as a resident scholar for, of all things, the United States Information Agency. In 1984, Inge was recruited back to his alma mater, Randolph-Macon, where he held the Robert Emory Blackwell Professorship in the Humanities (named for a longtime president of the college). There he stayed, teaching and researching, for the balance of his career — while also holding Fulbrights in Spain, Argentina, the Soviet Union and the Czech Republic, and lecturing in myriad other countries, often at the behest of the USIA. In 1992, he was recognized as a Virginia Cultural Laureate. In 2008, the Society for the Study of Southern Literature gave him a lifetime achievement award.

Tracing Inge’s scholarship, a near 60-year trail that winds through journal articles (more than 50), monographs, anthologies, pamphlets, curated reprints, catalogs and papers, presents a serious challenge. His work on comics ran parallel to his ample work on literature, paraliterature and humor. He participated in, and in fact helped build, several scholarly associations, worked with many publishers and kept looping back to lifelong interests, even as he explored new things. He was a tireless scholar of, especially, William Faulkner, humorist George Washington Harris (creator of the Appalachian rascal Sut Lovingood) and Charles Schulz. Of course, he also kept getting into other things. Inge’s first academic journal article may have been “William Faulkner and George Washington Harris: In the Tradition of Southwestern Humor,” published in Tennessee Studies in Literature in 1962 (during his time studying at Vanderbilt). In the years to come, he would often publish in journals of Southern studies, which was key to both his scholarly and personal identity. Inge’s first book-length publication appears to have been, oddly, but then again characteristically, a bibliography of faculty publications at Michigan State (published in 1966 by MSU). He would publish many bibliographies, reference books and sourcebooks over the years — perhaps the most famous being his Handbook of American Popular Culture (1978), which eventually went into three editions. Editing and bibliography were mainstays of Inge’s career; early on, he began curating editions of Harris’s humorous tales (1966, 1967), assembled the anthology Agrarianism in American Literature (1969) and oversaw the reissue of John Donald Wade’s 1924 biography of Georgia legend Augustus Baldwin Longstreet (1969). Much later, he would edit, among other things, Sam Watkins’ 1882 Civil War memoir Company Aytch (1999) and two editions of Oliver Harrington’s work, Dark Laughter (1993) and Why I Left America and Other Essays (1994).

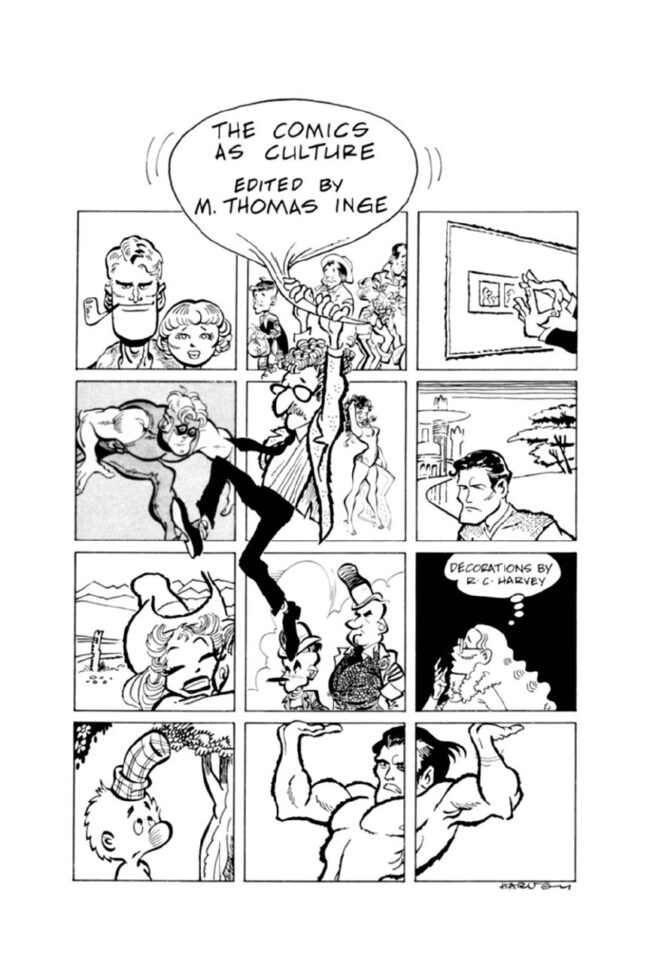

By 1973, Inge had begun championing academic work on comics. That year, he chaired a panel called “Comics as Culture” in Indianapolis at the third national conference of the Popular Culture Association, an organization he had helped build (the PCA acknowledged his history of leadership in 2018 with the Lynn Bartholome Eminent Scholar Award). Comics scholarship in the young PCA would take his imprint. Two years later, when the budding association began organizing itself into working groups or “Areas”, the “Comic Art and Comics Area” became one of the first. Inge would return to the title “Comics as Culture” more than once: in 1979, he guest-edited a special section with that title for The Journal of Popular Culture (vol. 12, no. 4), a section that included both drawings and an influential article by Robert C. Harvey (the article was later incorporated into Harvey’s monograph The Art of the Funnies, 1994). Later still, Inge published Comics as Culture (2000), a book that compiled material he had written over a span of years. Even as he pioneered comics studies within the PCA, Inge also helped found the American Humor Studies Association in 1975 and, during that period, co-edited a newsletter on American humor. Humor studies became a pillar of his career: witness the historical anthologies Southern Frontier Humor (2010) and The Humor of the Old South (2001), both co-edited by Inge with Edward Piacentino, and an early edited collection of criticism, The Frontier Humorists (1975). Through the AHSA, Inge influenced the leading academic society for literature scholars, the Modern Language Association, of which AHSA became an allied organization. Inge and the AHSA organized and chaired panels on comics at the MLA conference, including first-ever MLA comics event “What’s So Funny about the Comics?” which was a discussion with -- good grief -- Will Eisner and Art Spiegelman (New York, 1978), as well as, much later, what may have been the first academic conference session on Peanuts (Washington, D.C., 2000 — this writer got to participate in that one).

By 1973, Inge had begun championing academic work on comics. That year, he chaired a panel called “Comics as Culture” in Indianapolis at the third national conference of the Popular Culture Association, an organization he had helped build (the PCA acknowledged his history of leadership in 2018 with the Lynn Bartholome Eminent Scholar Award). Comics scholarship in the young PCA would take his imprint. Two years later, when the budding association began organizing itself into working groups or “Areas”, the “Comic Art and Comics Area” became one of the first. Inge would return to the title “Comics as Culture” more than once: in 1979, he guest-edited a special section with that title for The Journal of Popular Culture (vol. 12, no. 4), a section that included both drawings and an influential article by Robert C. Harvey (the article was later incorporated into Harvey’s monograph The Art of the Funnies, 1994). Later still, Inge published Comics as Culture (2000), a book that compiled material he had written over a span of years. Even as he pioneered comics studies within the PCA, Inge also helped found the American Humor Studies Association in 1975 and, during that period, co-edited a newsletter on American humor. Humor studies became a pillar of his career: witness the historical anthologies Southern Frontier Humor (2010) and The Humor of the Old South (2001), both co-edited by Inge with Edward Piacentino, and an early edited collection of criticism, The Frontier Humorists (1975). Through the AHSA, Inge influenced the leading academic society for literature scholars, the Modern Language Association, of which AHSA became an allied organization. Inge and the AHSA organized and chaired panels on comics at the MLA conference, including first-ever MLA comics event “What’s So Funny about the Comics?” which was a discussion with -- good grief -- Will Eisner and Art Spiegelman (New York, 1978), as well as, much later, what may have been the first academic conference session on Peanuts (Washington, D.C., 2000 — this writer got to participate in that one).

It is perhaps telling that Virginia Commonwealth University has eulogized Inge as a “[l]egendary comics and pop culture scholar” without noting the full breadth of his contributions as a literary historian, anthologist and proponent of Southern studies. It isn’t easy to encompass what he did in a few words, and it may be that, of all the innovations he encouraged, comics studies is the one most easily explained now — the revolution that is easiest to recognize as such. But Inge was, profoundly, a regionalist: a Southerner, in particular a Virginian, to his bones. He always affirmed that. Moreover, he was actively involved, for a long time, in two associations that seemed to split dramatically along populist-versus-elitist lines, the venerable MLA and the upstart PCA. With rare grace, Inge managed to walk his own pattern among consecrated literature, vernacular traditions and mass culture. Along the way, he wrote and did things that might surprise those who see him mainly as a comics scholar: for instance, he edited a volume of essays on Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1988) and co-edited Black American Writers: Bibliographical Essays (1978) and Russian Eyes on American Literature (1992). During the past decade, in his 70s and 80s, Inge kept pursuing certain enduring interests, for example editing The Dixie Limited: Writers on William Faulkner and His Influence (2016).

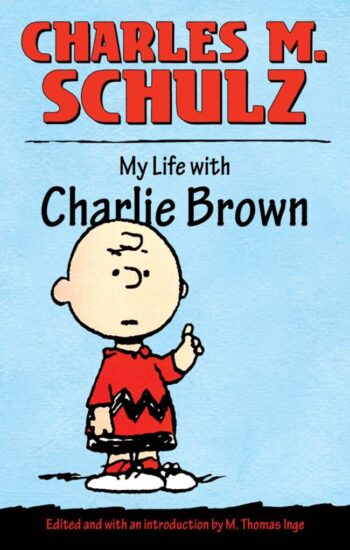

But of course it was as a comics scholar that I knew Tom best. I first met him in 1995, at the PCA conference in Philadelphia that introduced me to the Comic Art and Comics Area. That Area became my home at the PCA, and I seldom ventured out of it, not least because of the many wonderful scholars I met there. I could tell right away that the whole Area looked up to Tom reverentially and basked in his everyday approachability and warmth. In 1996, the Area began awarding an annual prize for outstanding conference paper called, of course, the Inge Award. What I didn’t realize at first was that Inge’s many years of cultivating comics scholars had begun to pay off not too many years before I came on the scene. At the University Press of Mississippi, Inge had established the first academic book series to take a special interest in comics, Studies in Popular Culture, which had launched in 1989 with Joseph (Rusty) Witek’s Comic Books as History: The Narrative Art of Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Pekar, as well as his own Comics as Culture. It was because of Inge that Mississippi’s then Director, Seetha Srinivasan, would meet with me at the PCA annually for several years after and patiently encourage me to submit my work once I had completed my PhD. Essentially, Seetha prospected among the up-and-coming comics scholars at the PCA (she and Inge made a great team). That’s how my Alternative Comics eventually got published (2005). Mississippi would go on to found three dedicated series on comics, the first two under Inge’s guidance: Conversations with Comic Artists, a series of interview collections launched with Inge’s own Schulz book in 2000; and Great Comics Artists, a series of monographs that followed in 2006. Tom approached me about doing a Conversations book on Jack Kirby, but what resulted was a Great Comics Artists entry instead, my second book, Hand of Fire (2012). Truly, the 40-plus books about comics that Mississippi has thus far published are all testimonials to Inge’s impact.

Inge remained deeply involved in comics and cartooning studies for all his career. In recent years, he edited a volume of essays by Schulz, My Life with Charlie Brown (2010), as well as Will Eisner: Conversations (2011), curated exhibitions focusing on comics adaptations of Poe (2008) and Twain (2009) and researched Disney animation. He contributed multiple times to John Lent’s International Journal of Comic Art and gave interviews to Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society (2019) and Brian Baynes’s fanzine Bubbles (2019, republished in IJOCA, also 2019), in which he reminisced about his career. Those conversations are a tremendous fund of information.

Inge remained deeply involved in comics and cartooning studies for all his career. In recent years, he edited a volume of essays by Schulz, My Life with Charlie Brown (2010), as well as Will Eisner: Conversations (2011), curated exhibitions focusing on comics adaptations of Poe (2008) and Twain (2009) and researched Disney animation. He contributed multiple times to John Lent’s International Journal of Comic Art and gave interviews to Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society (2019) and Brian Baynes’s fanzine Bubbles (2019, republished in IJOCA, also 2019), in which he reminisced about his career. Those conversations are a tremendous fund of information.

I last saw Tom at the first-ever conference of the Comics Studies Society (2018) at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana — a turning point in my life. It had been my honor to help guide the creation of the CSS and the election of its first governing board. That first conference, under the leadership of then CSS President Carol Tilley, went off resoundingly well, and Tom’s presence there felt reassuring and affirming. I fondly recall listening in on a conversation between Tom and Carol during which she interviewed him about his early activities in fandom. I was supposed to be doing something else -- my wife Mich and I were eating lunch, I think -- but my mind kept going back to the storied career of Tom Inge and all that he had wrought since those childhood days that sparked his undimmed love of comics. I wish to God I had had the good sense to buttonhole him for a few such conversations myself. Not only was Tom responsible for opening the door for me as a writer -- essentially, shepherding my first two books into the world -- but I think it quite likely that I never would have been part of an endeavor to found a Comics Studies Society without his encouraging example and concrete intercession in multiple instances. As a teacher, organizer and connector of people, as a living resource, and as a reader and thinker, he inspired me. He inspired many.

At that CSS conference, three years ago, Tom told me that he could hardly think of retiring. He liked his work too much. But, according to a tribute posted by Randolph-Macon College on May 20, he had indeed planned on retiring from teaching this spring — though of course he envisioned continuing with his research. His passing came as a shock to me; naturally, we think our mentors will live forever. Comics studies today owes an incalculable debt to this kind, stubborn and original gentleman. I know I do.

* * *

Thanks to Randy Duncan, Matt Smith and Carol Tilley for their help with this article.