It was Mother's Day weekend a few days ago, and I know exactly what you did. That's right: the unmarked vehicle, the blur in your peripheral vision - it wasn't acute paranoia, it was me! You took your mother out that weekend! To the Toronto Comics Arts Festival! You took her there so she could finally meet Taiyo Matsumoto, and then she told him all about how your youngest sibling was conceived during the initial English-language serialization of Black & White, and then the whole crowd applauded, and David Collier pinned a medal on her chest. I was sitting directly behind you. It was such a great time.

Except for the fact that you didn't get an advance copy of Suehiro Maruo's The Strange Tale of Panorama Island, which sold out within half an hour of the doors opening on day one.

It's cool. This column's here for you. And your mama.

To your left we see the case for a PAL-format dvd release from Ciné Malta; as far as I know, it is the only legit home video release for an English-subtitled version of animator Hiroshi Harada's Chika Gentō Gekiga: Shōjo Tsubaki, a 1992 anime adaptation of Mauro's 1984 opus Shōjo Tsubaki, localized by Blast Books in the '90s as Mr. Arashi's Amazing Freak Show. Contrary to the Ciné Malta website, my system insists that it's a region-free disc. It is *very* English-friendly, subtitling not only the film, but all of the bonus features, and even presenting the obligatory informative booklet in bilingual French/English format.

To your left we see the case for a PAL-format dvd release from Ciné Malta; as far as I know, it is the only legit home video release for an English-subtitled version of animator Hiroshi Harada's Chika Gentō Gekiga: Shōjo Tsubaki, a 1992 anime adaptation of Mauro's 1984 opus Shōjo Tsubaki, localized by Blast Books in the '90s as Mr. Arashi's Amazing Freak Show. Contrary to the Ciné Malta website, my system insists that it's a region-free disc. It is *very* English-friendly, subtitling not only the film, but all of the bonus features, and even presenting the obligatory informative booklet in bilingual French/English format.

Midori, as I will now refer to the film -- it's also been known under the more explicative title of Midori – The Girl in the Freak Show -- has attained a somewhat legendary status among older anime viewers and 'cult' movie fanatics of a certain generation; aside from simply *being* an anime made from a goddamned Suehiro Maruo comic, it was also known to have been drawn entirely by director Harada, who spent half a decade laboring over all 55 minutes of his one-man show, only to withdraw it from circulation at the end of the '90s and seemingly forbid any home video release.

The dvd of Midori, then, with Harada's full participation, acts to either dispel or explain some of the most common myths surrounding the project. This was not a crazy man's personal obsession painted in blood and pus in his bedroom; Harada was a great admirer of Shōjo Tsubaki upon its release, and -- noting the collapse of several larger-scale attempts to adapt the comic to film -- basically hounded Maruo with correspondence (a la the student filmmakers who often pop up in the letters page of Optic Nerve) until he relented.

It was 1987, and Harada (not to be confused with the gekiga artist Hiroshi Hirata) had already enjoyed some success as an animator on mainstream anime like Maison Ikkoku, in addition to having directed a few short animated films of his own. However, he knew that there was no way he was going to secure formal 'producers' to finance such a project, and so opted to perform all of the direct illustration duties on his own basically as a cost-cutting measure. By the time he had actually finished the animation duties, however, his achievement was impressive enough that outside parties began donating (or drastically discounting) their services for the actual shooting, voice acting, titles, etc. Harada even submitted the film to Japan's movie regulation board for guidance on self-censorship.

It was ultimately to no avail. Per Harada, in 1999, upon its return from an overseas festival screening, "the print" of the film -- possibly the only one -- was seized by Japanese customs and destroyed. The Ciné Malta disc appears to have been struck from a VHS master. This is why Harada has not attempted further Japanese screenings or a Japanese home video release; he is evidently not opposed to international video distribution.

Still, this is not the whole story.

As far as adaptations go, Midori is a pretty close one. Maruo's original scenario concerns the trials and travails of a naive, agonized 12-year old girl of the early Shōwa period (say, 1930-ish), whose broken, impoverished family situation results in her falling in with a gang of circus freaks, whose rough 'n ready counterculture clashes madly with Midori's desire to go on school trips and be a well-socialized girl. The down-and-out show is enhanced, one day, by the arrival of a dwarf psychic whose magic acts delight everyone. He becomes an understanding (if *very* controlling) lover to young Midori, though his violent nature eventually causes him to lash out at hypocrites that make up the 'civilized' audience of (war-ready) Japanese. The circus breaks up, and the dwarf leaves to start a new life with Midori, though alas, dear reader, he is killed by a desperate thief in a robbery, leaving poor Midori all alone again with the mocking recollection of the freaks she'd abandoned.

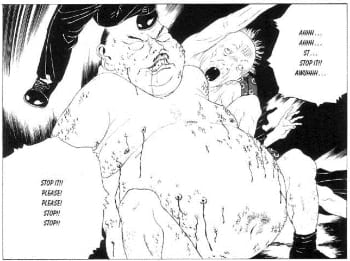

Harada rearranges a few events and expands on others, adding additional episodes of sexualized violence -- in an expanded prelude, Midori comes home to find rats gnawing on the genitals of her mother's corpse, and the taking of her virginity at the hands (or, in the absence, mouths) of the freaks is specified and made graphic -- but mostly hewing to Maruo's rather elliptic narrative style. As you can see above, Harada sometimes breaks Maruo's pages down into consecutive frames, copying Maruo's panels closely and then 'filling in' moments of additional activity (frame 2 above, occurring between panels 1 and 2), a bit like an in-between animator working from key frames by a senior artist.

The film even adopts a chapter-based format, hewing closely to the structure of the comic, though Harada's chapters are actually called "songs," which is important. As is the full Japanese title, again: Chika Gentō Gekiga: Shōjo Tsubaki, translating roughly to "Underground Projected Dramatic Pictures: Camellia Girl."

Midori, you see, was not envisioned as a normal theatrical feature. Inspired by the avant-garde theater and cinema of Shūji Terayama, which often added an element of live-action performance to cinema exhibitions, Harada debuted his film in a re-purposed shrine, with the audience led through a haunted house-style maze into a facsimile circus tent, where Midori was projected on three screens to the accompaniment of colored lighting, smoke, gunpowder, and a climactic whirlwind of cherry blossom petals raining onto the crowd. Moreover, it was accompanied by real circus acts and kamishibai demonstrations, which is to say a live-narrated picture story of the type active in the time of the film's action, a widely-acknowledged predecessor to post-war manga in its employment of cinema grammar (and future manga artists).

Indeed, Maruo's own Shōjo Tsubaki is allegedly based on an authentic girls' kamishibai tale of that very period, though the artist blends this sentimental evocation with a mean-spirited parody of contemporaneous shōjo manga, mocking the idea of his pure-hearted heroine's agonies leading to anything satisfactory in the way of societal or emotional reward. His is a Sadean perspective in which innocence is punished, though put to distinctly Japanese ends, in that Maruo most directly opposes the idea of tradition as anything to be honored. Instead, he fetishizes the aesthetics of fascist Shōwa as a perfect platform for tales of amorality and societal breakdown. In Maruo's world, sentimentality is an indulgence of privilege, while the poor, the rejected, the freaks understand the truth behind humanity: the rape, the violence, the fact that we are all basically animals, and that conformity to societal norms only facilitates less honest means of exploitation.

But then, as with Chris Ware, such criticisms don't get in the way of the fact that Maruo obviously loves old shit.

Harada loves it too. Midori is not the most lavishly-mounted animated film you'll see; there's a lot of panning over still images and sound effects/voices covering for a lack of motion, although it really doesn't look that much different from most of the bargain-basement television anime cranked out today (and it has a *terrific* synthesizer score by authentic Shūji Terayama collaborator J.A. Seazer, who later worked on the classic '90s anime Revolutionary Girl Utena). But I suspect Harada, who on the dvd cites the fine example of American comics/animation pioneer Winsor McCay -- whose 1914 landmark Gertie the Dinosaur also involved a significant live-action accompaniment -- is fine with a lot of his movie being still frames, many of them copied from another artist's work.

This, after all, is the essence of kamishibai. I'm not the first to suggest that Midori is something of an elaborate, modern day (circa '92) still picture story, and I'd even go so far as to say that the film's status as adaptation is especially fitting, in that the film is the work of one man, readily replicating and extrapolating from another storyteller's work, with his own pictures, in the way so many kamishibai storytellers operated. As a matter of fact, there was an earlier film project along these lines - 1967's Band of Ninja, in which filmmaker Nagisa Oshima (himself a distinctly counter-cultural figure, best remembered in the West for 1976's In the Realm of the Senses) edited together still images of a ninja comic by manga great Sampei Shirato, who was himself a kamishibai illustrator back in the day. In this way, Oshima cast himself as 'narrator' to Shirato's illustrator, though he did not take the extra conceptual steps of drafting new (often copied) illustrations himself, or elaborating on the original story as Harada did... and as did Mauro from the original Shōjo Tsubaki.

It is tempting to draw a political conclusion from all of this. Maruo's politics of anti-social violence read like a punk application of Shirato's own taste for bloody Marxism. Fellow leftist Hayao Miyazaki would eventually denounce the influential Shirato's worldview thusly: "If the world were truly filled with such hate and destruction, if that were how history was made, then everyone would surely have been dead by the Edo period." He could just as well have been talking about Maruo. Harada, meanwhile, on the Ciné Malta dvd, casts his animation in opposition to that of Miyazaki's Studio Ghibli, which he sees as exporting a monied, status quo fantasy of Japanese history to the West. "If his stories represent the official story of Japan," he says, "then Midori is a counter-story of Japan, one the Japanese State and powers that be have suppressed and tried to hide away."

One wonders, however, if Midori really could have kept it up so long as the old-school multimedia extravaganza its director had planned. A few paragraphs up I mentioned kamishibai as informed by cinema grammar; the Japanese cinema of the Shōwa period specifically clung to silent movie grammar for longer than the West, insofar as a certain live component existed in it as well, with a benshi typically retained to stand by the screen and accompany the film with a running narration and character voices. Amusingly, this is how the earliest American anime fandom functioned in the absence of subtitles at SF conventions, with the one Japanese-fluent person in the room pausing the video and explaining things to the rest of the audience.

Still, soon fansubs were a thing. Soon, the sound revolution hit the cinema. Soon, cheaply-available cinema-informed manga and gekiga -- and the slow rise of television -- relegated kamishibai to antiquity. Mostly, I watch movies on my laptop; it runs PAL-format discs, and I never worry about region codes. I watch more and rarer films than I ever could before. I love it, though I do still look at projects like Midori and I know it's a potent example of creative frustration, born from a real attempt to take its source manga's evil nostalgia for an earlier age and create an entire self-referential space for the experience of such: to be transported and challenged, shocked by smoke and noises, and controlled by the exact pacing of images dictated by one Hiroshi Harada, who now works a lot in video games. He was also a PA on Sofia Coppola's Lost in Translation, if the IMDB is correct. Maybe Bill Murray saw this film. Maybe underground, off the record, in the right conditions, through the maze, with an audience.

The rest of us are stuck reading manga at our own pace.

Alone in a room, with Suehiro Maruo.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday, or, in the event of a holiday or occurrence necessitating the close of UPS in a manner that would impact deliveries, Thursday, identified in the column title above. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

The From Hell Companion: Ooh, how appropriate! Following up Maruo with one of the greatest English-language graphic novels - a full-blooded horror comic to boot. Or, rather, this Top Shelf/Knockabout co-production is a 288-page softcover chronicle of the making of that book, authored by the comic's own artist, the irreplaceable Eddie Campbell, "complete with photos, anecdotes, disagreements, and wry confessions," along with many illustrations and samples of Alan Moore's original scripts. I can't wait to check this out. Samples; $29.95.

Edgar Allan Poe's The Fall of the House of Usher #1 (of 2): What the hell, let's make it an all-chills spotlight -- kind of uncanny, that -- with Richard Corben's latest and lengthiest from a new series of Dark Horse-facilitated Poe adaptations running in Dark Horse Presents (and 2012's The Conqueror Worm one-shot), colored in full by the artist himself. Preview; $3.99.

--

(Please note that Ivan Brunetti's Aesthetics: A Memoir may be appearing in some shops, despite its absence from Diamond's shipping lists; you will want to look at that, if possible.)

--

PLUS!

Eerie Archives Vol. 13: More shivers await, as Dark Horse brings issues #61-64 of the old Warren series, featuring art by the aforementioned Richard Corben, as well as Wally Wood, Alex Toth, Bernie Wrightson and others. Introduction by Tom Neely, of The Blot and The Wolf, whom I think is the first younger, working artist to contribute an essay to this series of influential works. Samples; $49.99.

Crossed: Wish You Were Here Vol. 2: Every so often I hear a whisper or two from people who're really into the webcomic for Crossed, a quasi-zombie series from Avatar Press, presented in a register they used to call "splatterpunk," which is to say 'probably not directly translatable to cable television.' It's still ongoing, still written by 2000 AD veteran Simon Spurrier, and now a second, 160-page color compilation is available, with art by Fernando Melek; $19.99 ($27.99 in hardcover).

Neon Genesis Evangelion Omnibus Vol. 3 (of 5): Getting back to Hayao Miyazaki, though - he has a new feature, Kaze Tachinu ("The Wind is Rising") opening this summer, and it seems he's cast Neon Genesis Evangelion creator Hideaki Anno as the lead character. Anno, of course, worked as an animator on Miyazaki's 1984 Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind movie; perhaps he sees things coming full circle, now that Yoshiyuki Sadamoto has finally been announced to complete this manga adaptation of Eva with its Japanese vol. 14, a mere 18 years after he started? Cherry blossom petals, fluttering. Anyway, here's Viz with a handy new packaging of vols. 7-9; $19.99.

Scott Pilgrim Color Edition Vol. 3 (of 6): Scott Pilgrim & the Infinite Sadness: Also in new editions, here's Oni with the latest colorization for Bryan Lee O'Malley's '00s alt comics superhit, a de facto deluxe edition hardcover featuring assorted comments and production materials from the artist himself; $24.99.

[another mess of Cinebook releases]: Or, "Eurocomics in English: The Adventure Continues" -

Valerian Vol. 2: The Empire Of A Thousand Planets (48 pgs., 8 1/2" x 11 1/4", $11.95)

XIII Vol. 16: Maximilian's Gold (48 pgs., 7 1/4" x 10", $11.95.)

Thorgal Vol. 6: City of the Lost God (96 pgs., 7 1/4" x 10", $19.95)

Betelgeuse Vol. 1: The Survivors (96 pgs., 7 1/4" x 10", $19.95)

Blake and Mortimer Vol. 11: The Gondwana Shrine (64 pgs. 8 1/2" x 11 1/4", $15.95)

Lucky Luke Vol. 27 & 28 (48 pgs., 8 1/2" x 11 1/4", $11.95)

All softcover, samples at the links. Been a while since I've seen any Thorgal. That's a fantasy series drawn by Grzegorz Rosiński and written by Jean Van Hamme of XIII, which itself has now reached the album before the Moebius guest shot. Betelgeuse is actually the sequel to a series titled Aldebaran, which Cinebook is also releasing; they're all clean-looking French-market sci-fi albums by Brazilian writer/artist Luiz Eduardo de Oliveira, aka Léo. Make sure you return these books neatly to the new release rack, so they don't crowd out the new Age of Ultron!

Doomsday.1 #1 (of 4): Certifiable Steve Ditko fanatics have Charlton Comics' entire publication history committed to memory, because you never know where the man might pop up. For example, Ditko had a back-up page in issue #5 of Doomsday + 1, and that's how I recognize the title of that immediate-post-apocalypse series, a Joe Gill-scripted joint also noteworthy for the longform color debut of artist John Byrne, who is now doing a solo re-imagining of that very concept (SOLAR FLARE DESTROYS SHIT, ASTRONAUTS TO THE RESCUE) at IDW. Delightfully loud cover; $3.99.

Alter Ego #117: Yes, the Roy Thomas old-timey fanzine is still coming from TwoMorrows, and this issue is particularly noteworthy for boasting a spotlight feature on Jay Disbrow: pre-Code horror artist, web cartoonist, and creator of the very first Fantagraphics comic, The Flames of Gyro, which I'm hoping will be treated to a Ken Parille-on-David Boring-caliber exegesis, if they don't want their magazine mailed back to them in tatters. Preview; $8.95.

Comic Book Creator #1: Oh come on, I'm kidding. Look, here's your magazine-on-comics for the week - a new TwoMorrows launch, edited by Jon B. Cooke, devoted to "the work and careers of the men and women who draw, write, edit, and publish comics, focusing always on the artists and not the artifacts, the creators and not the characters." First up on the cover is Jack Kirby, although chats with and/or coverage of Alex Ross, Kurt Busiek, Todd McFarlane, Frank Robbins, Neal Adams, Dennis O’Neil and others are promised across 84 color pages. Preview; $8.95.

--

CONFLICT OF INTEREST RESERVOIR: Quick, what's the opposite of Suehiro Maruo? I have no fucking idea, but it might not be too far off from Wandering Son, Shimura Takako's gentle study of children grappling with identity issues, now up to its fourth English-language volume, a 224-page hardcover aimed directly at you; $19.99.