What you are about to see is considered by some to be the best serialized comic book of the '00s.

Yes, The Winter Men - a story of Soviet super-soldiers adjusting the best they can to later life. An old-fashioned critics' darling and a perfect labor of love, as far as genre comics go. Its creators are writer Brett Lewis and artist John Paul Leon, who met as students at New York's School of Visual Arts, where Lewis -- himself an artist at the time -- studied under Walter Simonson and may have planned to draw some iteration of the comic himself. Little of Lewis' work as an artist is available for perusal; it can most easily be sampled in Paradox Press' 1997 anthology The Big Book of Martyrs. Provided it's the same guy.

I often feel the need to qualify things about Lewis; reliable sources are limited. As far as I know he's only ever given one major, career-spanning interview -- via a 2011 episode of the Bagged & Boarded podcast -- though it's safe to say he's been around for even longer than The Winter Men, the prolonged production of which involved rejection by the proverbial 'every publisher in town' before settling at Vertigo in the early part of the '00s. It then found itself transferred to sister imprint Wildstorm for its actual serialization, beginning in 2005, which wound up lasting until 2009 through format changes that ultimately resulted in the release of six individual comic books and a softcover compilation now fetching online prices of nearly $50.00 new.

So, the question is - why can you buy a similar collection for Lewis' next big comic for less than two dollars? Why can't I even find a review of the whole thing?

Fall Out Toy Works was published by Image from September of 2009 through July of 2010; it was five issues. Lewis is indeed the writer, through a potential hint at the project's relative obscurity can be glimpsed at his fourth-credited position on the cover above. Top-credited Pete Wentz was the bassist and primary lyricist for the band Fall Out Boy, the ostensible driving force behind the project; possibly in some effort at egalitarianism, his cover credit was re-issued collectively to "Fall Out Boy" beginning with issue #2, though it was perhaps too little too late, as the band went on 'indefinite hiatus' around that time. Nonetheless, fashion designer Darren Romanelli and visual artist/longtime Image contributor Nathan Cabrera remained credited as well in their capacities as co-creators (if not active creative participants) in what was meant to be part of a cross-platform fantasy barrage, inspired by cyberpunk anime and Disney movies and Blade Runner and song lyrics and a tour, I guess, which never happened.

In short, it was a licensed comic - the sort of thing that crops up at lot in Lewis' oeuvre. In 1996 he was editorial director of Motown Machineworks, a company which released comics through Image with the partial aim of producing movie vehicles for black stars. In 1998, Lewis worked with a different packager, Flypaper Press, on the Image series Bulletproof Monk; for his troubles was denied onscreen credit in the resultant Chow Yun-Fat vehicle. For a while Lewis was an editor at Marvel Music, focused on branded releases of comics featuring Alice Cooper, the Rolling Stones and others, though it seems none of the projects he worked on were released, or maybe even completed. At another time he was active in Allstar Arena, a publisher of sports comic books for release in stadiums, as far as I can tell - he and Leon seem to have collaborated on The Mailman, a sci-fi comic starring Utah Jazz power forward Karl Malone, though for the life of me I can't find a copy. Lewis also wrote Scooby-Doo and The Powerpuff Girls for DC's all-ages line, and an anti-bullying Spider-Man comic for Target stores, though maybe the most memorable of all these ventures came in 2010 2006, when Marvel released The Halo Graphic Novel, in which Lewis collaborated on a short story with no less than Jean "Moebius" Giraud.

Still, the best of these projects tend to be viewed with suspicion by connoisseurs, even those that prefer superhero comics of the sort that surrounded The Winter Men on the racks. Those are 'real' comics, aimed primarily at people who already read comics, while licensed comics aim for a wider, pre-established, casual audience, and carry a mercenary scent that overrides the desires of even funnybook populists. How much can a Brett Lewis really do if he's at the beck and call of fucking Fall Out Boy? How much of anyone's personality can persevere when occupied with supplementing the enjoyment of people arriving by way of devotion to something else? Hell, most of you reading this probably feel the same way about most Marvel and DC comics, smothering as they can be of the individual voice - and in its carefully tailored English-Russian cadence, the way in which its characters spoke, The Winter Men was all about voice.

And yet, Fall Out Toy Works is very much of a piece with that earlier series. Following a nondescript initial pair of issues -- concerning a sensitive maker of sentient robot toys who finds himself involved with a drowsy-eyed industrialist in a scheme to invent a real-feeling artificial woman for the latter's private life, the content notable mainly for Lewis' enjoyable deployment of accents, ranging from a Rabbi diamond manufacturer's patter to a hostess club employee's wildly eccentric Japanese-English -- the series' third chapter suddenly shifts its focus to an 'interlude' of the sort its writer used to fine effect in The Winter Men. Having successfully manufactured a 'real' girl in the Pinocchio mold -- Tiffany Blues, named for the Tiffany Blews cut off 2007's Folie à Deux -- the toymaker finds himself infatuated. He dreams of man-on-robot sex, and spends a troubling day of hooky with the free-spirited automaton, who sort of wants to be happy with her insanely rich boyfriend but also wants to dance and laugh and have experiences that aren't programmed into her.

The industrialist -- who controls the very sun that shines onto the metropolis of the comic! -- tracks the couple down and directs his robot goons to give the toymaker a sound thumping. A typical drama-building device, but... there's two complicating factors.

First, prior to the attack, the toymaker's Jiminy Cricket-like insect smartphone had suddenly stopped acting like his conscience as in the first two issues, turning to the reader on page three and decrying the usage of dreams in fiction as bullshit distractions from the meat of a scenario. He then announces the issue's title, and thereafter becomes a type of over-critical reader's surrogate, or maybe a frustrated editor, drawing our attention to the artificiality of the comic's narrative devices. You, the genuine reader, could probably write it off as yet another curious upheaval in a series that had already seen two colorists and two letterers participate under the supervision of two editors and two art directors, with production of its anime-look art housed in Singapore's Imaginary Friends Studios, where penciller Sami Basri would eventually step aside for one Hendry Prasetyo as of issue #4.

There was a three-month gap between issues #2 and 3.

The second complication was that in that time between issues, Lewis was present in a bar which was robbed, and he was beaten into a coma.

While unconscious, the toymaker dreams of Moebius, Lewis' own cohort, imagined as "Dr. Giraud," a Tezuka-like compassionate scientist dedicated to the pursuit of unrepeatable logic and the re-organizing power of movement, of dance. A giant robot attacks, and the teddy boy from the Folie à Deux album cover -- designed by Luke Chueh, another name of many involved -- stares at a clock and a fish. The clock begins moving when the fish stops, automation overcoming organics. The story seems to have stopped too, much to the cricket's dismay, though I don't know how much of Lewis' script had already been turned in for production. The teddy boy cries nonetheless.

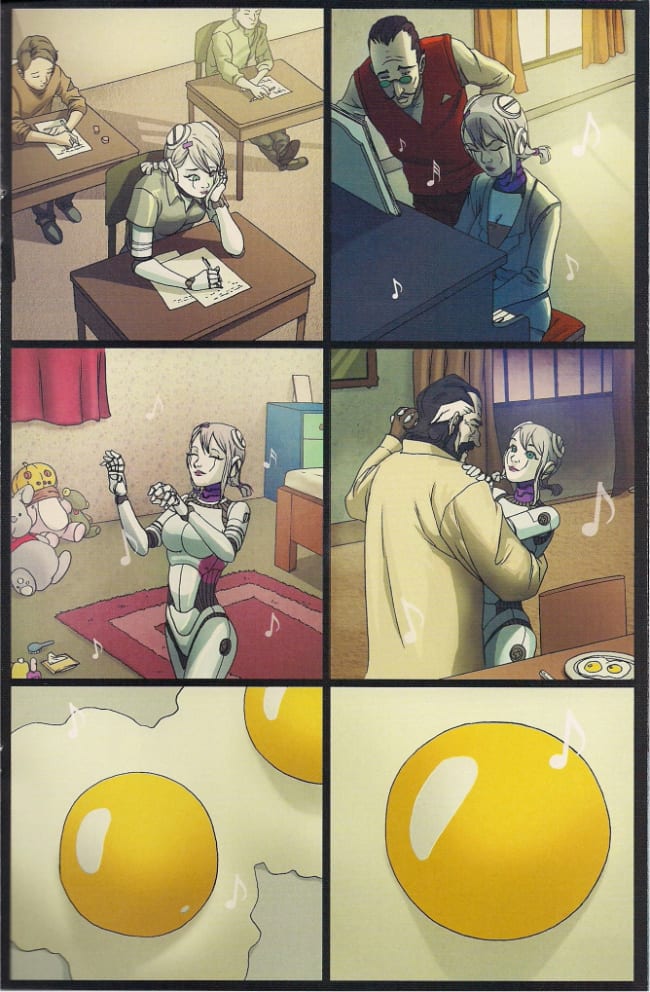

The comic continues to grow away from its original concept in issue #4, released two months after #3. The image of the sun recurs as eggs for breakfast by a ready-made servile wife: a symbol of male desire for power over society and women. The toymaker becomes obsessive while the industrialist cooks up a scheme to simulate outside experiences in his increasingly agitated robot lover by drugging her with additional memories, swapping out the linearity of experience with realistic dreams of living other lives. The toymaker's ex-hostess club girlfriend leaves him, continuing the theme of commodification of women, but now placing part of the onus on the comic's ostensible hero. Images become dominant, and fragmented.

As I hope I'm getting across, it is impossible to read this stuff the same way once you've become aware of its writer's situation at the time. Lewis told the Bagged & Boarded folks that his injuries left him temporarily with little grasp of linear time, acutely conscious of certain memories. These later issues of this tie-in comic seem responsive to that, if perhaps only through some quantum heave, though it is known that the fifth and final issue, released another three months after the fourth, was written during Lewis' recovery.

By its author's own tally, the script for #5 came out to 78 pages. The issue begins with the toymaker -- accompanied by weaponized chibi sidekicks and clad in mecha armor worthy of M.D. Geist -- assaulting the industrialist's headquarters, severing the umbilical cords connecting Tiffany to her dreams so that tachyons spill into the room and everyone's thoughts become real. The centerpiece of the issue is a five-page speech by the robot woman, holding forth on religion, memories, society, education, automata - pretty much everything, in a cascade of text pasted over altered and re-purposed images from earlier issues. Note how much of the above panels from issue #4 anticipate the background of these issue #5 scenes, creating a series of way points for the attentive reader to follow, coloring the connotations of the speech itself.

It's by far the most interesting use of art in the series, still adhering to an anime realism, but running alongside the text now as a solidification of abstract notions suggested by the text. Unavoidably, the reader notices hospitals, images of violence, fucked-up memories. Elsewhere, the cricket frantically comments on the cliches we're seeing - men confronting men over a woman. Tiffany repeats her displeasure again and again as the men witness the romantic and familial disappointments of their lives manifested in front of them. Oddly, it's suddenly very much like the narrative breakdowns memorable from some feature anime, Akira and the like. Eventually the girl gets up and leaves on her own, and men sort of wander away, their conflict stalled and this cross-platform tie-in comic's narrative left dislocated, though its themes remain quite intact.

Originally, the series ended with a one-page denouement seeing Tiffany and the toymaker reuniting in the glow of late-realized love; it's the most artificial thing in the whole robot-obsessed project, seeing the 'nice' guy -- long ago proven to be extremely creepy, all things considered -- bagging the gal who's finally puzzled out how awesome and sweet he really is. At risk of sounding dramatic, it read to me like a betrayal of the series' progression, its evolution into conflict.

The collected edition, however -- which, a tie-in to the last, sports a backmatter conversation between Wentz & Romanelli that acknowledges the existence of the comic itself in approximately one paragraph -- changes this ending. Or, rather, it deletes the epilogue, so that what you see just above is the last six frames of the story, with the cricket laying smashed on the ground, memories leaking from his hand, as the teddy boy, the icon of the band's own presence -- fittingly, a peripheral presence in the whole story -- laments the situation and justifies his own aloofness.

Things don't end as much as stop, which completes this odd, troubled work very nicely. Fall Out Boy is silenced, alas, but Brett Lewis is still around.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday, or, in the event of a holiday or occurrence necessitating the close of UPS in a manner that would impact deliveries, Thursday, identified in the column title above. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

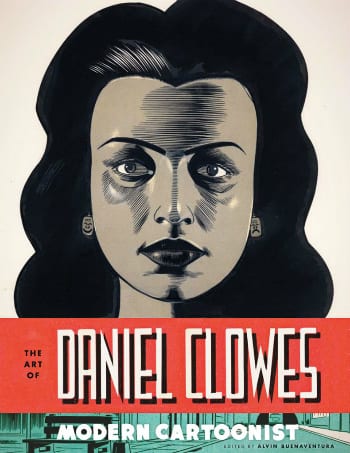

The Art of Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist: You've heard plenty about this already, so note only that this Alvin Buenaventura-edited hardcover monograph from Abrams is now imminent, if not impatiently waiting on your warm, soft arms in stores where it showed up last week. Original art and rarities are promised at 9 1/4" x 12", as are essays by Chris Ware, Chip Kidd, Susan Miller, Ray Pride and our own Ken Parille, plus a new interview with the artist and an introduction by comedy writer George Meyer; $40.00.

Rohan at the Louvre: Being the fourth exhibit from NBM's line of English translations for comics produced in association with the Louvre, and, more importantly, the first to come from an artist best known for drawing people being kicked in the face. Hirohiko Araki is the creator of JoJo's Bizarre Adventure, a never-ending boy's action saga that's been running in one form or another since 1987 and enjoys some appreciation in North America for a special blend of boundless energy and manic creativity, which appears to be manifesting in the 'art' comics realm as an almost Shintaro Kago-like desire to fuck around with the comics form in striking and rather gross ways - I won't soon forget a woman's cheeks flaking loose into pages from a book. The plot involves a manga artist confronting a cursed painting (IN THE LOUVRE) that triggers bodily mayhem of a type sure to warm the hearts of old souls who remember the author's early '80s bio-mutation opus Baoh. Delightfully, this is the actually the second manga-character-romps-in-a-Western-museum original in as many years -- owing to last November's release of Professor Munakata's British Museum Adventure, from 2001 Nights artist Yukinobu Hoshino and the British Museum Press -- but the potential for wondrous insanity is squarely on the present. Samples; $19.99.

--

PLUS!

Sharknife Double Z: Elsewhere in international manga influence, artist Corey Lewis and Oni Press offer a sequel to a well-received 2005 fight comic (re-releasing this week with a new cover) concerning a restaurant busboy who transforms into an ultimate fighter when peril awaits. Lewis has a really energetic style and a good grasp of crazy shonen manga fight pacing, so this will probably be a breezy 136 240 pages of entertainment. Preview & interview here; $11.99.

Garbage Pail Kids: I was a little young for the great Cabbage Patch Skirmishes of those early '80s winters, but like so many of my peers I was just old enough to appreciate the classic gross-out art of John Pound, even divorced from the initial parodic signal of Topps editors Mark Newgarden & Art Spiegelman. Exposure to anti-Garbage Pail jeremiads in the Catholic school newsletter probably helped; I don't recall any Congressional hearings, but this stuff really did freak some authority figures out, albeit the same authority figures that vehemently insisted Beck's Loser was a siren call for teenagers to commit suicide several years later. Maybe we were born and bred as fodder for Pound, Tom Bunk, Jay Lynch and others, all of them showcased in this 5 1/2" x 7 1/8" Abrams collection of Series 1 through 5, 1985-86; $19.95.

B.P.R.D. - Hell on Earth: The Pickens County Horror #1 (of 2): In more contemporary horrors, the Mignola wing of Dark Horse now begins alternating a B.P.R.D. side-story with the main continuity for a little bit. The co-writer is now editor Scott Allie, the artist is Jason Latour, and the subject matter is vampire kinfolk holed up down south. Preview; $3.50.

Gone To Amerikay: It's good to see that Vertigo continues to pursue original graphic novel projects, particularly those promising 144 pages filled with art by Colleen Doran, colored here by José Villarrubia. Written by Derek McCulloch, it's a period(s) piece(s?) about the experiences of Irish immigrants to the United States over the course of a century; $24.99.

Sláine: Books of Invasions Vol. 1 (of 3): Now here's a different kind of Celtic tale, from Simon & Schuster's line of 2000 AD releases. It's the start of a 2002-06 storyline for writer Pat Mills' long-lived barbarian character, with the 'realistic'-yet-somehow-completely-and-I'd-argue-self-awarely-artificial stylings of artist Clint Langley present and accounted for; $19.99.

The Push Man and Other Stories

(&)

Abandon the Old in Tokyo

(&)

Good-Bye and Other Stories: Big vintage manga drop from Drawn and Quarterly, although maybe these Yoshihiro Tatsumi collections are additionally 'vintage' in tracking probably the most successful attempt by a non-manga-dedicated publisher to tap into the J-comics boom by contextualizing manga in a manner which the publisher's established audience might find interesting and appealing. I know the pendulum has swung a ways on Tatsumi, but I really like these lil' nasties, culled from a variety of years and sources; they strike me as scenes from a medium's troubled adolescence, as if the SuspenStories of EC had been allowed to develop further out into gloom and muck, albeit by the parameters of developing popular manga aesthetics. Anyway, now it's all in softcover, in anticipation of the publisher newest Tatsumi release, the anthology Fallen Words, due next month; $16.95 (each).

Dororo Omnibus Edition: Of course, you can always go back to the 20th century's pop manga source with this 848-page all-in-one Vertical compilation of Osamu Tezuka's fantastically berserk 1967-69 action comic, something of a partial precursor to Black Jack in its weird medicine but rather unique among translated Tezuka works in the velocity of its sword-swinging bloodshed. A hell of a piece, minor or not; $24.95.

Torpedo Vol. 5 (of 5): Finally, in a reprint-heavy week, we have IDW wrapping its collections effort on this Jordi Bernet-drawn crime comics classic, 144 pages to end ya; $24.99.

--

CONFLICT OF INTEREST RESERVOIR: John Benson follows up his contributions to 2010's excellent Four Color Fear: Forgotten Horror Comics of the 1950s with a solo editorial excursion, The Sincerest Form of Parody: The Best 1950s MAD-Inspired Satirical Comics, culling choice bits from humor magazines by Atlas, Charlton, Harvey and the like; $24.99. And readers that missed out on Thomas Ott's 2005 collection of wordless works can now enjoy a softcover edition of Cinema Panopticum; $16.99