It was with great interest that I read Rodrigo Baeza's note last December that Chantal Montellier, among the most fascinating of the Métal Hurlant artists, had recently enjoyed an English-language release for one of her books, 2008's Franz Kafka's The Trial: A Graphic Novel.

This would be the first of its kind -- translations of Montellier's work have been otherwise relegated to crumbling back-issues of Heavy Metal -- so you can imagine my surprise at discovering the book was actually created for the English market (via the UK-based SelfMadeHero), and indeed shared a writer, David Zane Mairowitz, with a prior Kafka-related comics project: 1993's perpetually semi-obscure yet undeniably Robert Crumb-illustrated Introducing Kafka, aka R. Crumb's Kafka, aka a present, plain vanilla Kafka -- the R. Crumb a presumption at this point -- per the exhausted souls at Fantagraphics. Naturally, I had to have it; pragmatically, I got it used, being a four-year old literary adaptation loosed, one might guess, into the snarling din of bookstore access, which wasn't terrific for publishers but managed a thrifty boon for second-hand buyers.

What happened next was magnificent, almost as terrific as the time I imported an exhibition catalog from London, only to find an official document from the British Counsel lost inside, detailing attendance figures at a certain continental museum, as well as the dinner menu for the opening gala, upon which the artist in question had sketched his way in ballpoint pen around the costliest table stains I've yet to encounter:

YES YES POST-IT NOTES! It appeared my book had once belonged to a student, a good-hearted soul who couldn't bear to mark up their lovely assigned comic. My imagination raced! This was my chance to hold a dialogue with a departed partner, a dialogue on a book in dialogue with a dead writer, arranged by the live writer behind a prior, dead edition of much the same content! My head spun! Soon I'd be the one scoring five-figure hardcover print runs on my half-whimsical, half-snarky, insightful-by-way-of-deliberate-'accident' and cleverly-critical-of-cleverness commentaries on Andrei Tarkovsky movies -- which, by chance, I had been amassing under my bed -- and not that monster Geoff Dyer.

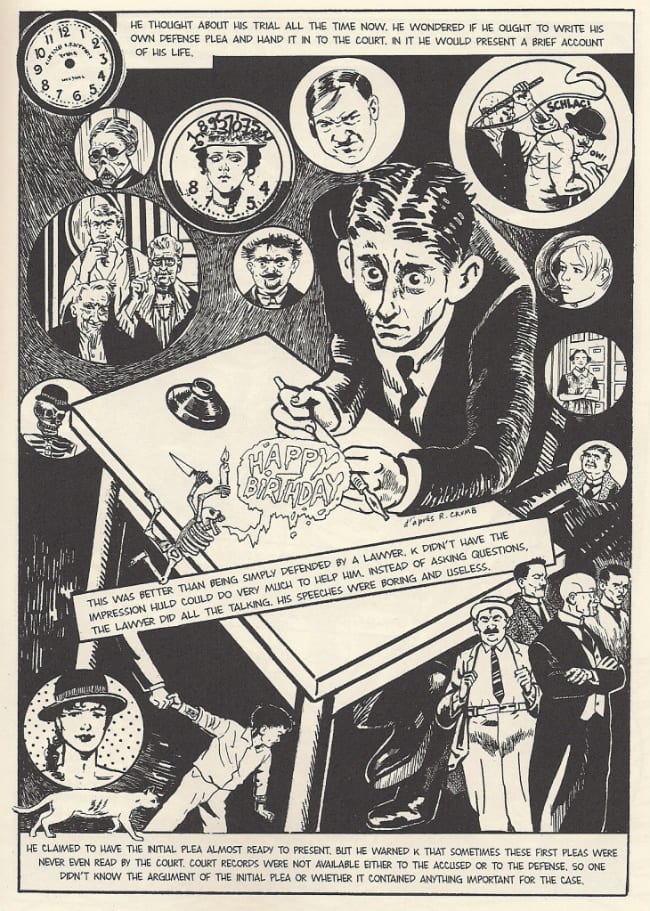

Immediately, my collaborator 'noted' (HA HA) the tension between the realism of Montellier's character art and the sketchiness of her decoration on the opening page. This is the same character art as seen on the cover of the book, and immediately contrasts with Crumb's cover to the first edition of its predecessor:

The Crumb image, of course, is drawn from a fairly well-known photograph, while I can't find anything quite like Montellier's rendition. However, that's not the point. What matters is that Montellier's character image seems as if drawn from life, almost like she's paraphrasing another artist's rendition of the same Franz Kafka shot. This is vitally important to understand, because this image -- and I mean exactly this image, probably by way of digital cut 'n paste -- will recur inside the book as protagonist Joseph K.'s default expression, nakedly reminding us of the artificiality of his positioning against Montellier's doodled skeletons and decorative candles and torn-up papers - the "ripped up page," which also recurs to rend the fabric of reality, of reliability.

Here we see Joseph K.'s journey through the ghetto to his initial hearing. Gradually, Montellier replaces prim, orderly panels with torn rags, initially just dominating panel space but soon, by the bottom of the first panel on the second image, replacing the panel borders themselves so that the gutters become gashed out of the stuff of Prague itself, a fearsome (yet still basically ordered) capriciousness that embodies the nature of the bureaucratic apparatus Joseph K. is up against - they are literally the world he must live in, and from this concept Montellier embarks on a full-scale harassment of the comics form. Where her '70s works -- at least the ones I've read -- drained the blood from genre comics so that icy critique could gleam deadly, now the artist does open violence to the page.

In a way, this focus (and no doubt the ensuing decades) have loosened Montellier up - that's a terrific manga-like image in panel 4, its sensation causing the bottom border to explode into flames, igniting Joseph K.'s passion so that when he flees in panel 6 his ardor resembles both fire and also as a rip in the wall, in the page, so that he might presumably escape out the back and into the obverse sequence, should the next room somehow fail him. These anxieties, as devotees know, mirror Kafka's own ambivalence over "the disease of the instincts," so that the presence of sex manifests as a universal (page) disruptor in parallel to the similar destruction wreaked by the courts: an assault on Joseph K., on Kafka, who would prefer to burrow into writing and stay there.

I'd hoped my collaborator had appreciated these compelling factors.

"Oh what the fuck, you incandescent twit!" I screamed, into my pillow, "yes, he's a fucking candle and the wall has grabbed him, you are efficiently summarizing WHAT WE CAN PLAINLY FUCKING SEE LIKE YOU'RE WILLIAM MAXWELL FUCKING GAINES, AAAAGH." I rolled over and took my pulse for the sixteenth time that day; I could already feel the radiance building in my chest. Of course it wasn't a heart attack - I just believed it was, every time. I was going to die, and the villain Geoff Dyer was going to pass me out again, just like the time he stole my prom date.

I mean, what kind of high school girl goes to the prom with an acclaimed middle-aged British essayist and novelist?

...

The best kind.

Yet in collaborations, we cannot easily separate the concerns of one contributor from another. Writer Mairowitz, fifteen years earlier, had intended Introducing Kafka as a response to the cultural shorthand and academic over-interpretation he saw as plaguing the Kafka oeuvre. Thus, he placed much emphasis on the autobiographical elements active or latent in Kafka's stories, typically framing them as a sort of externalization of troubles on the record in the author's copious letters. In tandem with Montellier, the "symbolism of head" is primarily to fuse "Joseph K." with Kafka himself, in a stiff enough way so that the artist does not let you forget that this fiction is a construct around a real person's experience, one we can't hope to animate all that much.

It is reductive, perhaps, but it meshes well with Montellier's approach, particularly as she begins acknowledging her writer's prior book in the context of her own. Look at the circular panel 4. Along the bottom: "CRUMB."

It is another paraphrase; Montellier is not tracing, but drawing Crumb's own work into her own. In this way, she facilitates both context and criticism. Context from taking an illustration of Kafka's real-life meetings with authors and intellectuals and casting them as Joseph K.'s drinking buddies, so that these small interactions with people interested in Kafka's writing -- indeed, with Max Brod, who would defy his friend's wishes and publish his works instead of destroying them after his death -- are a corollary, palliative relief from the agony that haunted Kafka/K. The criticism comes from looking to the whole Crumb page, introducing Kafka's great love, Milena Jesenska, which Montellier then pastes down in abridgement next to a grinning, dialogue-free nudie-cutie, mid-transformation into death itself. The artist is cognizant, I will guess, of the presence of women in Kafka's work as extant only so that he might be affected and duly reminded of his fragility.

And what does that say of Robert Crumb?

"[T]he old convoluted, labyrinthine self-doubt" is nothing strange to Crumb, and I will not be the first to suggest a possible kinship between him and Kafka, who sweats on these pages like a dozen other Crumb men. Perhaps identification is more necessary for Crumb, who is in the end a literalist, filling in Kafka's spaces with cartoon details and psychological acuity, like a proper illustrator working for hire.

Montellier, on the other hand, surrounds her paraphrase with clippings from elsewhere in her book, stripping Kafka of his agonized love letters and isolating him in fragments from the artist's torn reality. She is an analyst, not here to create reality, but to assess its friction with artifice, its tear. And so, as Mairowitz's text mostly accompanies Crumb, who forms his own world on the page, it blends totally with Montellier, who harasses the world, peering in, positioned as the shadows and threats bedeviling Joseph K.

In his Zona, Geoff Dyer writes of identification with works of art, and of the luck involved with that. It so happened that one time, while watching Kafka director Steven Soderbergh's remake of Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris -- which the filmmaker denied was a remake, though Dyer knows better -- he became more acutely aware than usual that actress Natascha McElhone looked especially like his wife: in a movie, as we cultured folks all know, about a man encountering images of his dead wife. And as the movie continued, and McElhone changed form, she looked more and more like Dyer's wife, so that he found himself utterly enveloped in the film, to a more perfect degree than all the tricks of cinema craft could have hoped to accomplish.

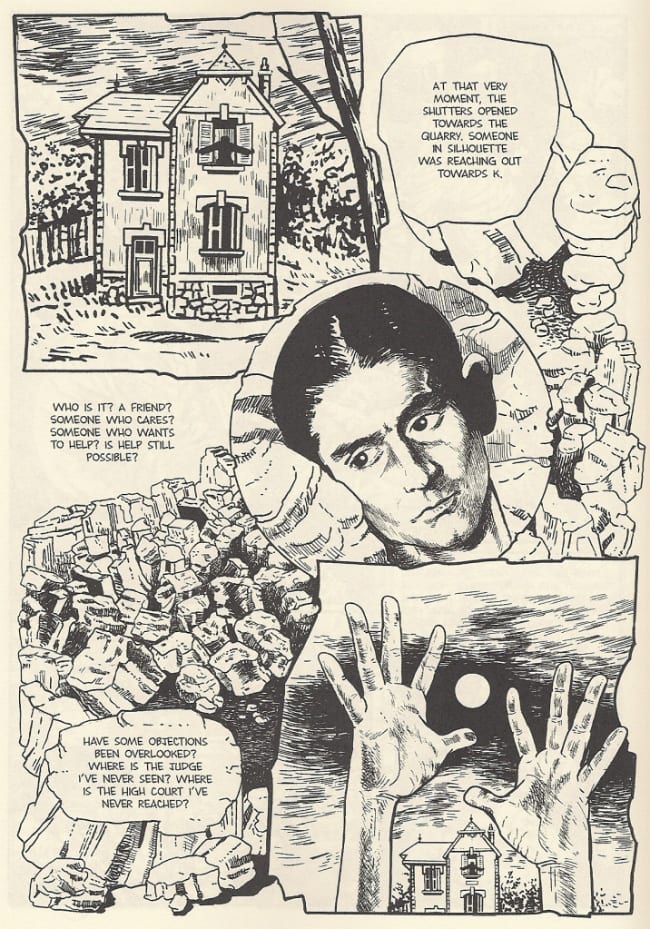

A quiet triumph of Crumb’s book is how all of the protagonists inside of Kafka’s stories look distinct from one another, yet still somehow carry a bit of Kafka inside them. Yet for Joseph K., Crumb seems to most directly blend the author with himself. As he waits for death, as a semi-inhabitant of the world, Crumb commands some power and poignancy, enveloped as he is in his traditional comic book storytelling, united with his own anxious male characters.

And at this critical moment, right at the end of the book, Montellier suddenly holds back. It is the damndest thing in the comic. She does not collage Crumb, or paraphrase him, or confront him, but becomes him, in taking his page layout and replicating it in her own style, the ripped borders of her panels suddenly behaving in homage to Crumb's shaky, handmade boxes and circles: leaving the evidence of Crumb's personality on the page.

It is beautiful, it is beautiful, it is beautiful. It's an understanding, a meta-empathy accompanying the mysterious extending of hands from the distant house, which Mairowitz's mocked scholars would call the presence of God, far away from Joseph K. Here, the hands join two artists, in a symbol of unity's potential at the end of all things.

I will now confess I've neglected by journalistic responsibilities and used the tools of theater and memoir to achieve a dramatic arc in all this long-winded shit. Really, my dealings with my collaborator ended on page 31 with the last of the post-it notes, which made me laugh so much. C'mon! That wilting, flaccid "everywhere" - immediately, I forgave everything.

In fact, as I paged through the book, I noticed post-it residue on several pages; my partner had removed a lot of notes before putting the tome up for sale. I imagined her shaking his head at all this riotous stuff and abandoning her studies - dropping out of school, in fact, so he could travel, like Kafka never really did, attending parties and taking lovers and dancing, learning proper French and reading straightforward comics and becoming a rich and famous translator, like Kim Thompson, and splashing Geoff Dyer with mud from her zooming car.

What a wonderful place you live in, my friend, and what a splendid adventure you've had, secondary only to the greatest adventure of all: buying used books on the internet.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday, or, in the event of a holiday or occurrence necessitating the close of UPS in a manner that would impact deliveries, Thursday, identified in the column title above. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

Sammy the Mouse Vol. 1: In which artist Zak Sally's own La Mano 21 (via a successful Kickstarter campaign) tends to a 6" x 8", 104-page collection of the three extant issues of his 2007-10 Ignatz series, previously published by Fantagraphics & Coconino. I greatly enjoyed this stuff during its serialization, sort of an ominous funny animal series involving camaraderie and potentially divine intervention on the characters' manufactured world; it's hard to summarize. Note that this is not a complete story, as future book-format volumes are expected to complete the series, should everything go well. Samples; $14.00.

Dinopopolous: But if it's new short-form comics you demand in the old 8.5" x 11"-ish Ignatz format, the UK-based Blank Slate Books' Chalk Marks line has you covered with this 26-page release from Nick Edwards, in which a boy and his dinosaur embark on a dangerous mission opposite nefarious lizards, "[c]ombining out-and-out fun with insane metaphysical illustrations," per the publisher. As with the old Ignatz books, everything in this line will probably be worth looking at, should your shop elect to import it. Video preview; $7.99.

--

PLUS!

Ragemoor #1 (of 4): Being the reunion of writer Jan Strnad and artist Richard Corben for a new b&w Dark Horse series about a living castle, "nurtured on pagan blood, harborer to deadly monsters!" I don't see how this wouldn't be my front-of-Previews choice for the week, but that's just me. Preview; $3.50.

Eerie Presents: Hunter: Meanwhile, Corben is not in this 232-page Dark Horse collection of b&w Warren horror magazine content, through it's notable anyway as the first of the publisher's comprehensive collection of serials from the latter years of the magazines' lifespan, by which time they'd become a sort of counter-mainstream of fantasy or sci-fi inflected adventure, shot through with an especially grim, horror-informed worldview, like a vaguely evil 2000 AD. This one's a 'future barbarian'-like scenario involving a fellow with an odd helmet defending hope on an irradiated Earth; it was created by Rich Margopoulos & Paul Neary, and ran intermittently from 1973 to 1982 (if we're counting guest appearances, which Dark Horse apparently is). I particularly liked a one-off Jim Stenstrum/Alex Niño episode which functioned as the latter's introduction to the Warren magazine fold in rightly eye-popping style; $17.99.

Prophet #23: And insofar as some notions are eternal, Brandon Graham's own future barbarian take on this Rob Liefeld creation here concludes artist Simon Roy's initial run. I believe we're next into two issues with Farel Dalrymple, and then an issue written and drawn by Graham himself. Preview; $2.99.

Take What You Can Carry: I remain fascinated by the types of graphic novels released by enormous book publishers like Henry Holt and Company; not too long ago there was rhetoric flying around about how these things would sap the vitality from the form, dragging it down into a popularized morass of literary convention. Mostly, they just seem to flit into and out of existence, like messages from a parallel Earth, which speaks as much to the Balkanization of comics (or publishing) 'scenes' as anything else. Anyway, this is a 176-page project from Kevin C. Pyle, concerning the linkage between a '70s kid and a Japanese-American teenager forced into an internment camp during World War II. Samples; $12.99.

Ichiro: Another exhibit! This one's from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and artist Ryan Inzana (whom I recall from 2003's Johnny Jihad), 288 pages depicting an American boy sent to live with his grandfather in Japan after his father dies in Iraq, setting off an encounter with mythological figures; $19.99.

Undertow: But this is a rich enough week that you get a small press original option as well, a Soaring Penguin Publications release of comics by Ellen Linder, promising "DANCING!! DRUGS!! DECEIT!!" right on the cover. It appears to be a coming of age piece set at Coney Island in the 1960s. Preview; $19.99.

Dark Horse Presents #10: It was initially set for last issue, but this latest installment of Dark Horse's house anthology should be the one with a new Andrew Vachss prose story, illustrated by Geof Darrow. Also, Evan Dorkin should have some comedy stuff, and a few of the serials finish up, including Al Gordon's and Thomas Yeates’s Tarzan piece. Preview; $7.99.

John Carter: The God of Mars #1 (of 5): If there's one bookshelf-ready comic I've seen absolutely everywhere in the last few months -- comics stores, big box bookstores, pretty much in any place you could expect to find a comic that won't wilt on the edge of a table -- it'd be Archaia's release of Jim Henson’s Tale of Sand, an unproduced screenplay adapted to comics by artist Ramón Pérez. I'm sure the Henson name has something to do with that, but Pérez's art is of an intensely colorful and dynamic sort that catches the eye immediately - one imagines there's folks out there waiting to see his next project, and here it is, a Marvel release of work based on the Edgar Rice Burroughs creation, also factoring into some movie you might have heard of. The colorist is Jordie Bellaire, and the writer is Sam Humphries, one of the more talked-about dedicated scriptwriters in recent indie genre comics. Preview; $2.99.

Rocketeer Adventures 2 #1 (of 4): In which IDW again revives Dave Stevens' movie serial comic creation for an anthology series, which -- if its anything like the last one -- will marry some very accomplished visuals to extremely light stories. The participants here include Stevens collaborator Sandy Plunkett (with writer Marc Guggenheim), Bill Sienkiewicz (with writer Peter David), and Stan Sakai, with Art Adams offering a pin-up. Preview; $3.99.

Monocyte #3 (of 4): Also from IDW comes a new installment of this labor of love from writer/artist Menton J. Matthews III ("menton3") and co-writer Kasra Ghanbari, a dark 'n smeary, designed-to-the-hilt comic book comic-cum-texty illustration showcase of the sort on which the publisher built its name with Ashley Wood. Note that Matthews has even gone so far as to compose a tie-in album of music related to the series, under his alternate name of Saltillo. Preview; $3.99.

House of Five Leaves Vol. 6 (of 8): Your manga pick, from Viz, as Natsume Ono continues her feudal swordsman drama; $12.99.

Clive Barker's Hellraiser Masterpieces #10: Tempted as I am to invoke Tom Spurgeon's old line about how it must be fun to live in a world with this many masterpieces, I will instead note that this Boom! reprint series is now covering some old Sam Kieth-drawn content, and that stuff's generally worth flipping over to. Preview; $3.99.

Cartoon Monarch: Otto Soglow & the Little King: Yet the Golden Age of Reprints continues apace, now with IDW bringing 432 pages surveying the career of Hearst newspaper and New Yorker cartoonist Soglow, including selections from all over his career -- presumably including The Ambassador, sampled in #286 of our print edition -- but largely focusing on "hundreds of pages" of The Little King. Edited by Jared Gardner, with an afterword by Ivan Brunetti; $49.99.

Elektra: Assassin: And finally in reprints comes a new hardcover edition for the best Frank Miller-related comic. I know, I love Ronin too, but my heart will always belong to this delirious Bill Sienkiewicz jaunt, which seems more and more to have predicted the trajectory of Miller's writing in the 21st century, and even, in a way, how his comics have sought to look in their devaluation of narrative composure; $24.99.

--

CONFLICT OF INTEREST RESERVOIR: If you didn't see it last week, gird your loins for Nancy Is Happy: Complete Dailies 1943-1945, presenting the Ernie Bushmiller classic from materials scanned mainly from the collection of Dan Clowes, who provides an introduction (as well as, potentially, a huge art book courtesy of Abrams, though Diamond does not have it set for release this week); $24.99.

--

PROPOSITION.

Chantal Montellier is so goddamned awesome.