Connoisseurs know this as the face of quality. All other may consider themselves On Notice - the new Cryptic Wit has arrived.

How can I summarize Cryptic Wit? Very little is known about its author, Gerald Jablonski, though he's a genuine product of the late American underground period, having made his publishing debut in 1976 in the sixth (and penultimate) issue of Art Spiegelman's & Bill Griffith's influential anthology Arcade. Highly intermittent anthology appearances followed in the likes of Snarf and Tantalizing Stories, before Fantagraphics released a 48-page compilation of his works: Empty Skull Comics (1996). Jablonski was credited therein as "Writer, Artist, Auteur, Genius," suggesting a certain amount of self-awareness bolstered by the occasional on-page drug reference and a crisp sense of visual absurdity, broadcast through meticulously stippled 'serious'-looking illustration of the sort often associated with Michael Kupperman.

Nonetheless, Empty Skull Comics had some undeniable force of opacity about it. In his introduction to the book, Jim Woodring mused on whether Jablonski was mad, highlighting "that alarming glass-hard veneer of isolated intellect that distinguishes the product of a bona fide lunatic." This did not, however, prevent Jablonski from applying for a Xeric grant - and lo, in the hallowed month of September, 2001, it came to pass that the Xeric Foundation instantaneously justified its whole being in funding the production of Cryptic Wit #1, released the next year.

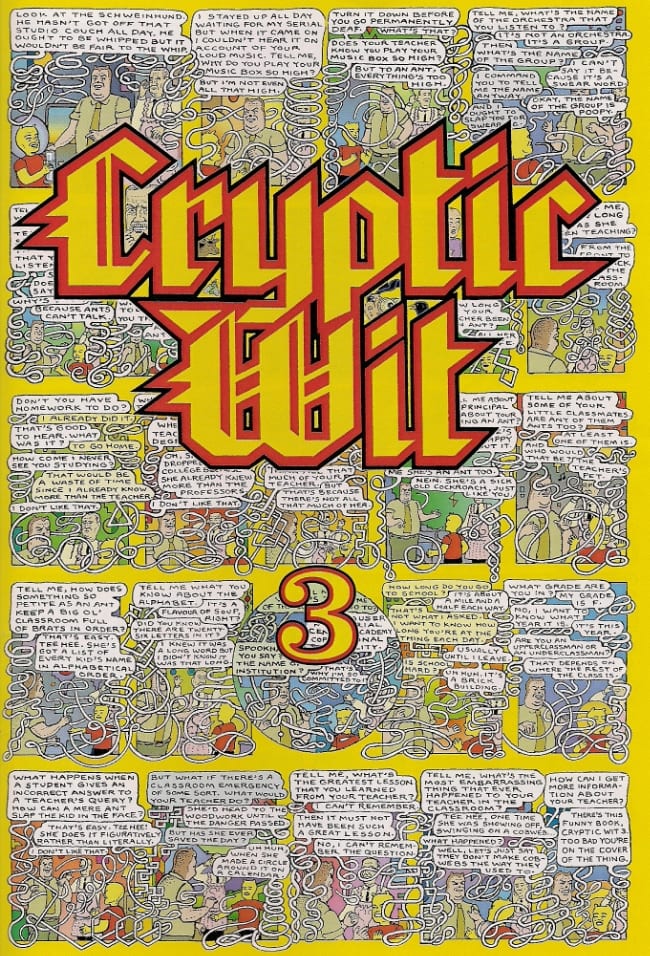

This is what Cryptic Wit looks like from a distance:

Mind you, the first issue was in b&w. Jablonski put an ad in The Comics Journal, and I sent a postal money order to his home address in New York. It would be one of the most important comics I'd ever read, precipitating an explosion in my mind comparable to my first experience with ACME Novelty Library, except where Chris Ware expanded my parameters of what the comics form could do, Jablonski remapped the entirety of my qualitative expectations, demonstrating that comics could be made 'wrong' -- as wrong as conceivably possible -- and still accomplish an enlightening and entertaining effect. What Fort Thunder did for some, what "weird comics" perhaps do today, Cryptic Wit did for me: opposing the sacred geometry of word/picture balance and novelistic/cinematographic narrative pace beloved of the critical majority, the received wisdom, and gesturing toward a new and singular way.

This is not to say many intelligent and sensitive minds don't find Jablonski's work difficult or boring or stupid or even flat-out impossible to read. The three extant issues of Cryptic Wit -- #2 arrived in 2008, bringing the series into full-color, while the new #3 bears a copyright date of 2012 -- are packed-to-the-gills comic books, with stories on the front and back covers, the inside-covers, and all 32 interior pages, with every one of those pages bearing an average of 27 panels, and sometimes over 50 words of dialogue per panel. Moreover, nearly every single story is exactly one page in length, and hews to one of three formulae, which I will now detail:

--

1. The Howdy Stories

These thrilling vignettes concern Howdy -- a bear-faced man with an authoritarian disposition and a thinly-veiled sentimental streak -- his yellow-faced, imp-like nihilist nephew Dee Dee and "A Friend of Howdy's Nephew," who is an older gentleman in a pink apron who never speaks or contributes to the story in any way whatsoever, despite appearing in every panel.

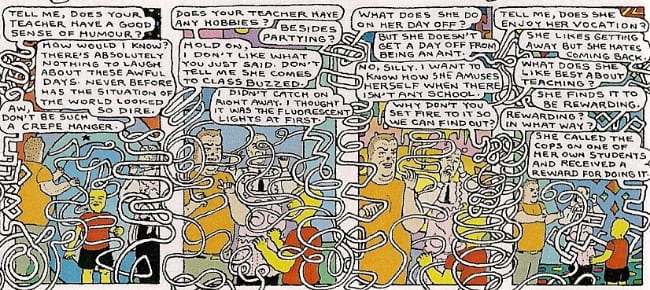

Typically, the story begins with Dee Dee listening to his favorite band, Poopy, the abrasive volume of which ruins Howdy's enjoyment of an entertainment serial. (An occasional variant sees the crew on vacation at Mount Howdy, a large mountain that closely resembles Howdy.) Howdy and Dee Dee engage in a pun-laden tit-for-tat, which *always* results in the unexpected revelation that Dee Dee's teacher at school is an ant, *always* causing the rest of the story to focus on Howdy's exasperation at the situation, sometimes resulting in his visiting the school himself, but more often just leading to additional back-and-forth.

Backgrounds shift, in a George Herriman manner. German or Germanic-sounding words pepper the dialogue. Dialogue tails wrap and warp wildly around the characters, both emphasizing the endless, winding nature of their conversations and forcing the reader to isolate the words from Jablonski's tiny drawings. This is not like Dinosaur Comics, or The Angriest Dog in the World - everything is drawn new, every time. Every setting is slightly different, every time.

Everything is always the same, every time, in the macro sense, though the denouement may focus on an important lesson taught by the ant teacher, or a message for our troubled world, or just continued dialogue that happens to stop at the end of the page. The more things change...

--

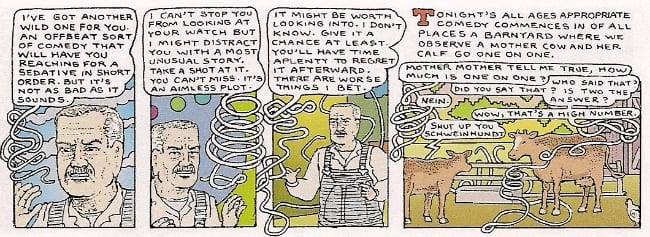

2. Farmer Ned

There's a little more (but somehow also less) variation in place with Jablonski's oldest character, Farmer Ned, a chatty-yet-standoffish man of the soil who suggests Garrison Keillor crossed with that guy down at the sheriff's office who's really concerned about his concealed carry permit.

Each story begins with Farmer Ned either lamenting the state of the world -- given that the character has been around since the mid-1970s, his continued worry over grave times functions as a joke in and of itself -- or hyping the reader up in an extremely hyperbolic manner for the story to come. Sometimes the introduction is so prolonged and repetitive that you're halfway down the page before anything happens. Eventually, though, we shift gears to talking animals in the barnyard, some of whom are rowdy, some of whom are nice, and almost all of whom find some counterpart to have long, pun-laden discussions with, on the road to an oddball moral ending, or sometimes no particular ending at all, or sometimes Farmer Ned wrapping up the adventure with thoughtful comments in his characteristic style.

"And there you have it, a scandal averted. And in its place an old fashioned sort of comedy that would offend no one in their right mind and that succeeds on every successive level. How I hate to see it end!"

--

3. The Comedic Interludes

The least common Cryptic Wit stories (only five of 'em in issue #3) are wordless affairs, focusing on the Spy vs. Spy-like travails of two boys -- one angelic and vaguely simian, one an exaggerated cartoon mutant -- who engage in form-bending fights with little purpose or resolution, save for (one guesses) exploration of comics paneling and character motion.

Since I'm always in a feisty mood with the new Jablonski release, let's call it a bridge between the psychedelic freakout shorts Rick Griffin or Victor Moscoso would insert into Zap and the more animated, observational experimentation of the Fort Thunder scene.

--

Yet Jablonski is always Jablonski; he does not 'let us in,' in the manner we've become accustomed to with alternative comics. You can sense all sorts of generational conflicts and apocalyptic worrying in his stories, but in all candor, I suspect he has no more primal goal than to amuse and entertain the reader, like a commercial cartoonist. Frankly, the absurdest repetition of the early Adult Swim shows that launched around the same time as Cryptic Wit have wormed their way into accepted comedy cadence enough that I wonder if newer readers, once acclimated to the pace of the artist's pages -- DO NOT ATTEMPT TO READ THE WHOLE COMIC AT ONCE -- won't see Jablonski as an early adopter of the same funny challenges to safe, pre-processed narratives that the Williams Street gang eventually came to own.

Really, though, Cryptic Wit has a longer history to draw from. Don't even think about television - think of newspaper comics. I mean really formulaic gag strips, some of them inherited in the manner of a family business. Domestic Comedy Among Vikings. A Wizard in a Desert. Fantastic concepts, made palatable through repetition - eventually, they become such a part of the scenery that their jests seem to have pre-loaded into you at birth.

Jablonski's formulae are much more rigid, so that while the newspaper strips make the eccentric normal, Cryptic Wit makes the normal eccentric. What is more normal than an older man arguing with a young one? Or salt-of-the-earth animal fables? What is more normal to comics -- real, popular, widely-read, stuck-to-the-cubical comics -- than driving shit into the ground? By plucking at this tendency with a singular fury, Jablonski's routines ascend into perfect singularity.

Buy this comic. There is nothing else like it, you'll realize, above your suspicion that it's quite a damning lot like everything.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday, or, in the event of a holiday or occurrence necessitating the close of UPS in a manner that would impact deliveries, Thursday, identified in the column title above. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

Maximum Minimum Wage: Yes, hard as it is to believe today, certain aged souls do still primarily associate that august Walt Disney publishing associate Fantagraphics Books with underground comix grit by way of '90s urban 'slacker' culture... and now Image has taken even that away. Scandalize yourself, veteran reader, over this new 384-page hardcover compilation of observational semi-autobio comedy from Bob Fingerman, now teaming the 1997 Minimum Wage Book One original graphic novel with the artist's 2002 Beg the Question reworking of his 1995-99 comic book series Minimum Wage. Tales of art, porn, love, sex and hard-ass NYC livin' await, with bonus illustrated script excerpts from unfinished pages and a big gallery of tribute art. $34.99.

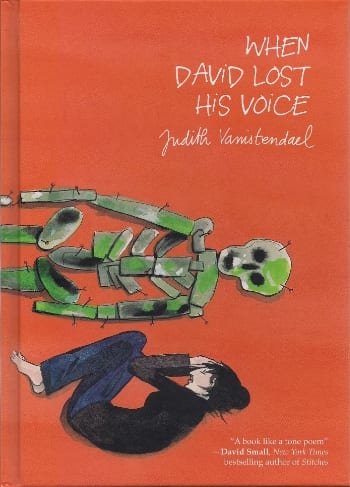

When David Lost His Voice: Ah, nothing quite like a Eurocomics translation from SelfMadeHero arriving with fanfare in North America via Abrams - we'll miss these days when they're through! This is a 2012 release from Flemish cartoonist Judith Vanistendael -- SelfMadeHero actually released their UK edition very quickly after the initial publication, so maybe you've seen it around -- whose 2007-09 series Dance by the Light of the Moon, a semi-autobiographical account of her romantic relationship with an immigrant from Togo, attracted a good deal of European press attention (as well as a 2010 all-in-one English edition, easily imported). This 280-page, 7" x 9 3/4" color hardcover is concerned with a broader domestic subject, as a grandfather is diagnosed with cancer and his family struggles to cope. Some very lovely drawing in here, ranging from stranded, Chester Brown-like isolated panels to explosions of full-bleed imagery. Bart Croonenborghs review (Dutch-language edition); $24.95.

--

PLUS!

Barry's Best Buddy: Toon Books continues to stride forward in hooking 'em young with this new kindergarten-appropriate 9" x 6" landscape-format hardcover original by Renée French, comics all-star and artist of several earlier children's books. Expect 32 color pages of adventure and friendship among talking beasties. In fact, why not plan your child's entire educational development as a journey from this to Grit Bath? Couldn't hurt. Video preview; $12.95.

All Crime Comics #1: This is a 36-page comic book from sketchbook and illustration showcase purveyor Art of Fiction that seems to have been initially released early on in 2012, though I don't think Diamond has distributed it to comic book stores until now. The story, written by an appropriately pre-Code like anonymous source, takes place in different time periods employing separate artists. I'm mentioning it here because I recall the Journal's Abhay Khosla doing an interview with co-artist Ed Laroche a few years back, and I remembered liking what I'd seen of his style. The other artist is one Marc Sandroni, and the colorists are Tony Fleecs and Andrew Siegel. Cover by Bruce Timm; $3.95.

Judge Dredd: Year One #1 (of 4): Just in case IDW's ongoing Judge Dredd comic book wasn't 100% authentic enough for jonesing squaxx, now the publisher presents a new 'early days' miniseries written by 2000 AD EiC Matt Smith, with an eye toward establishing a discreet continuity for the IDW version of the character. Keep your eyes peeled for a variant cover by Dave Sim(!!), though every copy will feature interior art by Simon Coleby, an accomplished 2kAD veteran who recently turned in some impressive work on the UK Dredd universe Trifecta crossover. At least one source is claiming that a North American edition of Judge Dredd: Origins (a similarly formative storyline by original creators John Wagner & Carlos Ezquerra) is also due this week, so pay careful attention. Preview; $3.99.

Action Comics #18: And speaking of Tharg's finest, this, I am assured, is actually the final issue of writer Grant Morrison's mixed tenure on the famous strongman. *Another* (former) 2000 AD EiC, Andy Diggle, will be taking over next issue, with art by former Morrison Batman collaborator Tony Daniel; $4.99.

Dark Horse Presents #22: Looking to be an especially old-school issue of Dark Horse's 80-page house anthology, insofar as Howard Chaykin is starting up a new alternate history serial (George Armstrong Custer: The Middle Years), while noted b&w boom title Fish Police returns (in color) with creator Steve Moncuse writing and drawing. Also expect a continuing serial drawn and co-written by Prophet artist Simon Roy, and an interview with Geof Darrow I think I recall solicited for over a year ago. Samples; $7.99.

The Unauthorized Tarzan: "Under the Loincloth"...? No, actually this 112-page Dark Horse hardcover collects an abortive 1964-65 attempt at a Tarzan comic by those loveable skinflints at Charlton, who (mistakenly) believed the character had fallen into the public domain. Whoops! Of special note for our purposes is the identity of the series' primary artist: Sam Glanzman, who produced the work concurrently with his run on Dell's Kona, a favorite of several readers of this column. Can the Komplete Kona be far behind?! Samples; $29.99.

Leonard Starr's Mary Perkins, On Stage Vol. 11: Your reprint brick of the week, a 264-page batch of newspaper strip drama from Classic Comics Press, covering November of 1970 through early June of 1972. The feature wrapped in '79, so there's not very many of these left to go. Introduction by Howard Chaykin; $24.95.

Vagabond Vol. 34: In which Viz gets itself current with Takehiko Inoue's swordsman serial, among the very best action comics going today. Note that vol. 35 is due out in Japan in about a month; $9.95.

Comics and Narration: Finally - well, I mentioned this last week, granted, but now Diamond is formally listing it for release to comic book stores, and you can totally read it in tandem with Jeet Heer's fine interview with the University Press of Mississippi's departing acquisition editor, Walter Biggins, surely a prominent force in academic writing on comics. Expect 192 pages of challenging theory and application by the Muscles from Brussels, Thierry Groensteen, following up on his revered 1999 study The System of Comics. Translation by Ann Miller; $55.00.