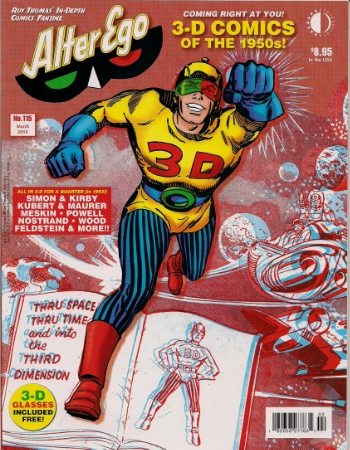

I am presently being told that I am in violation of Sec. 227.5a of the Comics Journal-Amazing Heroes Consolidated Statutes (the "Krackle Act" of 1982), requiring all duly reimbursed or otherwise defined "contributors" to the critical outlets identified hereinabove to publish at least one reference or allusion to Jacob Kurtzberg ("Jack Kirby") or Entertaining [Educational] Comics ("EC") per 30-day period. I'm so embarrassed; I've only ever had parking tickets before. Luckily -- just as the sheriff's deputy was knocking on my door! --I happened to be reading the glossy-ass rag to your left, last week's newest issue of "Roy Thomas' In-Depth Comics Fanzine," Alter Ego (#115), currently published by TwoMorrows, but founded by Mr. Jerry Bails way back in 1961 as a venue for celebrating the recent flowering of the DC comics Silver Age.

I am presently being told that I am in violation of Sec. 227.5a of the Comics Journal-Amazing Heroes Consolidated Statutes (the "Krackle Act" of 1982), requiring all duly reimbursed or otherwise defined "contributors" to the critical outlets identified hereinabove to publish at least one reference or allusion to Jacob Kurtzberg ("Jack Kirby") or Entertaining [Educational] Comics ("EC") per 30-day period. I'm so embarrassed; I've only ever had parking tickets before. Luckily -- just as the sheriff's deputy was knocking on my door! --I happened to be reading the glossy-ass rag to your left, last week's newest issue of "Roy Thomas' In-Depth Comics Fanzine," Alter Ego (#115), currently published by TwoMorrows, but founded by Mr. Jerry Bails way back in 1961 as a venue for celebrating the recent flowering of the DC comics Silver Age.

Befitting its status as breathing link to comics' past, today's Alter Ego is a pleasant slice of reminiscence, unfailingly enthusiastic about basically everything, if occasionally a little naughty with its enthusiasms; Roy Thomas remains the editor of record, and his most interesting contribution to this particular issue is a tacit tie-in to Marvel's upcoming Age of Ultron mega-crossover, bemusedly reprinting a George Evans/Martin Thall story from Fawcett's Captain Video #3 (June 1951) from which Thomas quite admittedly drew strong inspiration in creating Marvel's Ultron character with John Buscema in the pages of The Avengers. While unfailingly good-natured, it's nonetheless a piquant little reminder that beloved properties from *MARVEL's THE AVENGERS* are not only created by actual, living people, but very often drew strong influence from other, competing entities, particularly when die-hard fans like Thomas became contractors for just those corporate citizens.

Speaking of which, the feature article of Alter Ego #115 -- a heavily-illustrated survey of the 3-D comics fad of the 1950s by the late Ray Zone, glasses included, kids -- presents an amusingly rapacious portrait of good ol' EC, an undeniably important and influential publisher, the reputation of which has nonetheless tempted many a writer to present it as a sacrificial lamb for the sins of a nation, coating it in a martyr's bloody virtue. You don't as often hear about the time William Gaines, having witnessed the bonanza of sales enjoyed by Archer St. John off of 3-D comics processes developed by Leonard Maurer with Joe Kubert & Norman Maurer -- and having attempted and failed to develop a 3-D comics process of his own since the late '40s -- snatched up a license on an earlier 3-D process patent and, despite having not yet published any 3-D comics himself, proceeded to sue his competitors for infringement on the tenuous (and ultimately failed) claim that they'd based their own process on the earlier patent. But that's as much a part of the story as anything else dealing in cutthroat popular media.

(Dan, can I take off the ankle bracelet now?)

This was not the most interesting part of the magazine, however. A bit later comes part 7 (of 9) of an extensive tie-in with the Fandom's 50th Birthday Bash at Comic-Con 2011: the first half of a two-part interview with Richard Kyle, one of the earliest comics critics (and later an occasional Journal contributor). The oft-acknowledged source of the terms "graphic story" and "graphic novel," Kyle had Famous Funnies #1 bought for him off the stands in 1934 at the age of five, and read comic books into adulthood thereafter, making him a 'first generation' fan in good standing. A stray mention of the old Victor Fox line of titles caught my eye:

"His comics by the late 1940s were really bad. I don't know who was writing those, but on a Freudian level, it's some pretty disturbed stuff. It's so beyond the pale that I can't imagine anybody except somebody who was a sexual deviant of some kind wanting to read that stuff."

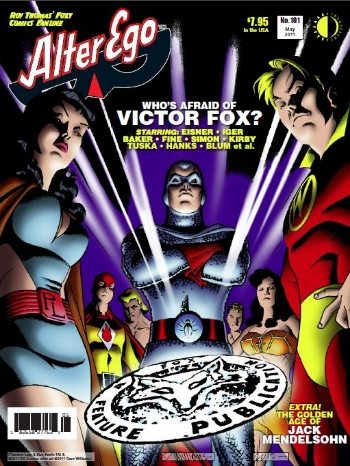

Obviously, I had to know more. I soon discovered that a prior issue of Alter Ego (#101) had reprinted the entirety of The Education of Victor Fox, a 1961 essay Kyle had written for Xero, a reputable comics-interested SF fanzine. Kyle attributed the unique appeal of Xero at the time to its use of "ordinary speech" as its editorial tone, although Kyle's own writing mainly demonstrates the shifting standards of the vernacular, in that it's more elegant in style than 95% of the comics criticism going today. Funny too:

Obviously, I had to know more. I soon discovered that a prior issue of Alter Ego (#101) had reprinted the entirety of The Education of Victor Fox, a 1961 essay Kyle had written for Xero, a reputable comics-interested SF fanzine. Kyle attributed the unique appeal of Xero at the time to its use of "ordinary speech" as its editorial tone, although Kyle's own writing mainly demonstrates the shifting standards of the vernacular, in that it's more elegant in style than 95% of the comics criticism going today. Funny too:

"'Back to my own people at last!' says Rima, and then she clears up any doubts about her age. 'I was only six years old when I fell down there fifteen years ago! How can I ever thank you?'

"'Your happiness is enough!' says Dr. Fung, who, despite his vigor, is apparently too old for the game. Barrister, however, is up on his addition, and knows what a girl's talking about when she tells him she's over eighteen. His hand reaches for her waist."

Such flavorful plot synopses take up a good amount of real estate in Kyle's piece, presumably for the benefit of readers suffering in an age without ready access to four-fifths of all comics at a few clicks of the mouse, the poor wretches. Indeed, Kyle -- working from limited materials and ignorant of history's favoritism -- disregards some prominent talents of the Fox Publications stable (such as Matt Baker, whose luscious good girl art on Phantom Lady unfortunately seems to have informed most superheroic depictions of the female form of the last quarter century - and what kind of adult diet needs that much cheesecake?!), and relegates business-focused anecdotes like DC's litigious demolition of Will Eisner's Wonder Man to a footnote. Kyle does, however, prove himself the first writer-on-comics (and maybe the first comics reader whatsoever) to blow a lavish chuckle in the direction of popular drunkard Fletcher Hanks:

"I can hardly believe it myself. If we can't have primitive art, why can't we have primitive trash? If Grandma Moses and Mickey Walker can become famous, why shouldn't Fletcher Hanks?

"(I can see Hanks now, standing proudly before his one-man show. He'd be blonde, of course, balding probably - ectomorphs have fine hair and usually begin losing it fairly early; thin - there might be the suggestion of a pot belly, though, after these twenty years; tall, surely. And long necked. Those early maturing, hard muscled, strong jawed mesomorphs who made his teens miserable trouble him some yet; and even now Hanks may have difficulty talking to the prettier feminine patrons. And the dark... well... the dark still bothers him a little, and he always reaches around the corner to turn on the switch in the gallery washroom before he actually goes in.)"

Truly it is snark that bridges the generations!

Still, from this excerpt, we can glimpse the true thesis of Kyle's essay. He is fascinated by that most second-half-of-the-20th-century of all aesthetic preoccupations: the division between "art" and "trash," which we might rephrase to 'high' and 'low' art. "Art," to Kyle, appeals to the emotions and the intellect, while "trash" appeals only to one, yet because trash is embodied in "the spirit of the thing," it can evade the scrutiny of art's critical practice, and, sometimes, in its perennial success, prove itself more important. Specifically, "costume heroes" of the Golden Age disregard personal interest in favor of "idealistic beliefs of justice and right," their dual identities emphasizing the capacity for the ordinary within the extraordinary, the simple humanity latent in the liberation of joyous power - "the hearts of these paper dolls."

Thus, the "[e]ducation" of Victor Fox -- "blue jeans gaping at the knees, being drummed out of kindergarten" -- was that his eventual darkening of the superhero milieu in Blue Beetle, amping up sexualized peril for the heroines and stripping down the villainesses' attire as the vogue for crime comics crept forward, only led to his rejection by a public given to "a mean streak of decency." On first blush, this seems patently absurd - the (adolescent) public quite obviously loved pre-Code crime and horror comics; that's why the Senate held hearings for a fast-crashing Bill Gaines to melt down over. But then, Kyle himself was a writer of adult-targeted crime novels, and perhaps saw a distinction between superhero comics and other types, the former appealing bang-on to impressionable children through the unique traits of the comics form, "where symbols can artistically replace representative realism more easily and convincingly than any other story-telling medium," allowing idealism to flower.

Such sentiments are very Alter Ego, very 'early fandom' - the soil, I will suggest, in which less delicate arguments were planted for the superhero genre as the ultimate and most perfect incarnation of comics, form and content inseparable, all other genres mere sorry pretenders and laughable pretense. Only the no-hopers make such declarations today, but they were not uncommon just decades ago, when -- ironically! -- the superhero practitioners of the '80s saw it necessary to darken the capes yet again, for superheroes-as-comics to carry the burden of the maturation of the art form as a whole... because what other comics could hold the public attention? Some of those hands pointed to the Stardusts, the Super Wizards, and theorized that if idealism was their center -- and it was often not -- then their function in wider and abusive, retrograde political frameworks showed a most dangerous naivete. Fletcher Hanks -- whom nobody but the RAW crew remembered at that point, admittedly, but bear with my hypothetical -- was not hilarious because of his deviations from proper idealism, but hilarious because he was so bluntly honest about the passion for violence inherent to the genre.

And the public bought it. WHAM! POW! NOT FOR KIDS! COMICS ARE NOT FOR KIDS, BECAUSE SUPERHEROES ARE COMICS, AND SUPERHEROES ARE NOOOT FOR KIIIDS!!

If nothing else, we are past that now. Personally, I am very sympathetic to the notion of superheroes embodying ideals. I mean, of course - I read Steve Ditko.

Ditko, a post-Fox Blue Beetle artist of some repute, is of the same generation as Kyle, which means he is also of the first generation of fans-turned-pros. And if Kyle inferred a latent idealism from the adolescent entertainment mechanics of the Golden Age, Ditko was perhaps the first working comics artist to approach the superhero genre specifically as an adult artistic vehicle for philosophic metaphor. The very foundation of the Ditko approach to art -- not "trash," not 'high' or 'low,' just art -- is that art must speak to the best in humankind, and his preference for costume heroes in transmitting such messages is very, very fandom.

And not just old fandom, oh no.

A few days ago on Twitter, the writer-on-comics Graeme McMillan asked why Vertigo never seems to be considered in discussions of "diversity" (both in terms of character representations and hiring practices) regarding DC Comics. Several responses boiled down to 'no superheroes at Vertigo,' which is correct, yet there's still more to it.

When I read a lot of (let's say) feminist superhero criticism, I sense a profound connection to Richard Kyle, and his own invocation of the idealistic capacity of superheroes. Heroines, in this calculus, ought to be inspiring. Empowering. Superheroes ought to lead the way, culturally, in positive depictions of powerful, good women, in comics, movies, television - everything. From there, the greater society might be galvanized. That these vehicles for unique societal change are owned and operated by gigantic, potentially rapacious corporate citizens is simply the terra firma of today, and to acknowledge that the capacity for accessing such change is held legally and exclusively by these monolith arbiters is only more reason why they should observe the great responsibility lashed to great power and hire diversely.

It is indeed critical work to push for a more diverse Marvel and DC. Yet I confess -- from my position of privilege, mind you, having never wanted for role models in popular media for all my life -- that I tend to blanch, a little, at this tacit concession of cultural capital to the mega-companies. Of course, this is not a universal attitude in comics feminism, but is central to so much of superhero fandom, no longer concerned so singularly on an art form routinely enjoyed by 0.1% of the population of the United States at absolute most, but riding shotgun, as you fancy, in the cockpit of the giant robot that is a branding-crazed pop culture that loves shit that's 50 years old 'cause in an excess of options folks will always plunk down for stuff they recognize. Victor Fox didn't need to learn anything. William Gaines: nothing. If they would have only survived, they would, eventually, have won, by virtue of having survived. This is the state right now, which could only have been imagined by Richard Kyle and Steve Ditko, and younger Roy Thomas, and all the other early men of a primal comics time.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday, or, in the event of a holiday or occurrence necessitating the close of UPS in a manner that would impact deliveries, Thursday, identified in the column title above. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

On the Ropes: Make no mistake, though - attempts *were* made at serious, adult, longform comic book serialization concurrent to and apart from the Dark Age of superheroes, and one of the most prominent examples was Kings in Disguise, a 1988 Kitchen Sink miniseries adapted from a play by scriptwriter James Vance and drawn by Dan E. Burr, a sturdy cartoon realist. The collected work -- a tale of Depression era rail-riding -- enjoyed a new W.W. Norton publication in 2006 for the 'literary' graphic novel age, and now comes an all-new sequel by the creators, advancing the timeline to 1937 and covering labor unrest and circus life in these United States of ours. Awesomely, the publisher has secured separate pull quotes from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, superhero Dark Age overgods, quietly reminding us (or, me) of the tricky historical context in which the original flowered. A 9" x 11" hardcover, 256 pages in b&w; $24.95.

Nemo: Heart of Ice: And look at that - Alan Moore! It's a regular The Spirit: The New Adventures reunion up in here, just in time for Will Eisner Week! God, that was such a smooth segue. When I finally croak, the priest's just gonna say "the segues" and drop the mic, as I've detailed in my will. Anyway, this is the latest from The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen -- drawn, as always, by Kevin O'Neill -- now in the form of a Euro-style 56-page hardcover album focusing on a supporting (anti?)heroine descended from the Jules Verne character. I've heard that this story marks a return to the jaunty-bleak action style of the first two League volumes, which should be welcomed by a wide swathe. From Top Shelf/Knockabout. Preview; $14.95.

--

PLUS!

World War 3 Illustrated #44: Also hailing from the '80s, but earlier -- I think it debuted at roughly the same time as RAW in 1980, making it one of the debutante post-underground 'alternative' comics -- is this famous magazine of politicized comics and reportage, presently into a run of 7" x 9" themed issues. This time around, it's "Being the Other," and the features include a first look at an autobiographical project by Lebanese artist Barrack Rima, plus comics from or about Egypt, Palestine, Quebec, and American areas affected by Hurricane Sandy. Distributed by Top Shelf, 120 pages in b&w. Preview; $7.00.

District 14: Contrary to the typical expectation of Franco-Belgian comics as long-ish color albums that arrive basically whenever they're done, this b&w Pierre Gabus/Romuald Reutimann collaboration -- a mystery story set among anthropomorphic critters in an early 20th century American newspaper strip-looking milieu -- was actually published monthly in twelve 22- or 28-page segments in 2007 and 2008 by Paquet, and only later compiled into proper 'albums' by Les Humanoïdes. Now the English-servicing Humanoids has a 304-page, 7.7" x 10.5" all-in-one hardcover ready to please anyone who caught Pierre Wazem's & Frederik Peeters's Koma last year and hoped for something (maybe) similarly cartooned and eccentric. I think Reutimann's only prior publication in North America was through a few bits of Humanoids' Lucha Libre series at Image; his stuff looks nice, and an entire second series by the same team is already finished in France, so there might yet be more. Foreword by Jeff Smith. Preview; $39.95.

Spera Vol. 2: This is Archaia's second hardcover expansion of creator Josh Tierney's fantasy webcomic, a pretty high-gloss production all around, but noted here for the participation of Prophet artist and Old City Blues creator Giannis Milonogiannis as one of the primary collaborators. It's 6" x 9" and 168 pages. Samples; $24.95.

The Casebook of Bryant & May: The Soho Devil: British comics history remains a preoccupation of mine, particularly the crucial period of the 1970s, in which the scene began its transition toward the more aggressive stylings of Action and 2000 AD. Among the artists to debut at that time was Keith Page, best known (by me) in 2kAD as a John Hicklenton colorist, but likely more prominent for a whole lot of war comics. Diamond is now making available a project he recently completed with prose author Christopher Fowler, an old-school hardcover Annual-type release dedicated to comics and miscellany starring two of Fowler's paranormal mystery characters. From prolific Alter Ego advertisers PS Art Books, who are also responsible for approximately one billion volumes of American Golden Age comics reprints by now. Soft colors, looks lovely. Sample page; $24.99.

Johnny Red Vol. 3: Angels Over Stalingrad: But if it's actual '70s war comics you demand, Titan has another 112 pages of British youth in Soviet skies from Tom Tully & Joe Colquhoun, the latter of whom I believe left the strip after the materials collected here to co-create Charley's War with eventual 2000 AD founding father Pat Mills. As a bonus, Garth Ennis has been penning historical essays for all of these hardcover releases, which now seem primed to inadvertently tie in with the conclusion to his own Soviet WWII saga in Battlefields over at Dynamite; $19.95.

Judge Anderson: The Psi Files Vol. 3: Oh, hey - here's 2000 AD itself, with 304 pages dedicated to most (not all) of the remaining uncollected contributions writer Alan Grant made to the popular psychic heroine of the title. Featuring the excellently-titled Arthur Ranson collaboration Satan, along with other pieces detailed by Douglas Wolk here; $32.00.

[umpteen Cinebook releases, yet again]: Jesus god, the British do know how to save on shipping. If you're tolerating this column, though, you must like the Eurocomics, and here we've got -

Blake and Mortimer Vols. 8-9 (The Voronov Plot, The Sarcophagi of the Sixth Continent Part One, all post-Edgar P. Jacobs material) (8 1/2″ x 11 1/2″, 64-72 pages, $15.95 each)

Lucky Luke Vols. 12, 22-24 (The Rivals of Painful Gulch, Emperor Smith, A Cure for the Daltons, The Judge) (8 1/2″ x 11 1/2″, 48 pages, $11.95 each)

XIII Vols. 8-13 (not the Moebius stuff yet, that's vol. 17, 7″ x 10″, 48 pages, $11.95 each)

Orbital Vols. 3-4 (newer poppy sci-fi, still ongoing, Sylvain Runberg & Serge Pellé, 8 1/2″ x 11 1/2″, 48 pages, samples here, $13.95 each)

SPOOKS Vol. 2 (newer scaaary cowboys, Xavier Dorison & Fabien Nury and Christian Rossi, 7″ x 10″, 56 pages, sample, $13.95)

The Chimpanzee Complex Vol. 3 (newer *serious business* sci-fi, wraps the series, Richard Marazano & Jean-Michel Ponzio, 8 1/2″ x 11 1/2″, 56 pages, sample, $13.95)

Long John Silver Vols. 1-2 (newer seafaring exploits, begun in 2010, still ongoing, Xavier Dorison & Mathieu Lauffray, 8 1/2" x 11 1/2", 56 pages, samples here, $13.95 each)

Please print out this page and present it to your local comics merchant, who is sure to have every one of these softcover treasures readily in stock.

Battle Angel Alita: Last Order Vol. 17: Not European, but also possessed of thousands of intimidating pages of backstock, here is Yukito Kishiro's metal-flesh blood ballad, which Kodansha has now brought up to date with the Japanese releases; $10.99.

Carbon Grey Vol. 2 #3 (of 3): Image stuff (slick division), with Paul Gardner, Khari Evans, Hoang Nguyen, Kinsun Loh and Joffrey Suarez brewing up the sort of wildly complicated world-building you don't see married to such heavy realist painterly art at all anymore. Preview; $3.99.

Prophet #34: Image stuff (gangly division), with Simon Roy now working again with Brandon Graham. Preview; $3.99.

Joe Kubert Presents #5 (of 6): Joe Kubert, in the manner of Joe Kubert, with a Sgt. Rock story written by Paul Levitz, and other assorted shorts; $4.99.

Batman Incorporated #8: I hear Jean DeWolff dies in this one. Spoiler-laden preview; $2.99.

Unearthing: Finally, we return to Alan Moore for your not-a-comic of the week, because the Magus has plenty on his plate that doesn't directly implicate our favorite shit. For example, in 2006, Moore contributed an essay to London: City of Disappearances, an anthology edited by one of his key influences, the great Iain Sinclair; the subject matter was Steve Moore, no relation, a British comics writer of some experience, and another critical influence on Alan Moore. Then, in 2010, the piece was adapted into a musical extravaganza for stereo and iThing, the deluxe edition of which included copious photography by Mitch Jenkins, who would later direct several short films from Moore's screenplays. Now Top Shelf and Knockabout (them again?) present the latest issue from this most fecund topic, a 184-page color book reorganizing the text into a barrage of fonts and poses. Probably the closest Alan Moore will ever get to a full-scale fumetti graphic novel, should you be longing for exactly that. Available in 8.5" x 11.75" softcover, and 11.75" x 16.5" hardcover. Samples; $29.95 or $74.95.