As you have probably heard, the manga artist Jirō Taniguchi died this past Saturday. I'll leave the summation of his life and work in more capable hands, as my own familiarity is strictly limited to those works we've seen translated to English - not an inconsiderable amount, but far less than the total output of an artist who'd been publishing professionally since the early 1970s.

Still, I did notice a few interesting things in the reportage surrounding his departure. For example, The Magic Mountain -- a mid-'00s serial which, to my knowledge, was never even collected in Japanese, let alone translated to English -- has unexpectedly been cited several times among a very small handful of his notable works. I suspect this is because the Belgian publisher Casterman, which disseminated word of Taniguchi's death in the west, released a French-language edition back in '07, and presumably made note of that in a press release; venues then repeated the information in English environs, a veritable dye pack bursting against their unfamiliarity with the artist's oeuvre. It's okay: that's how these things are reported in the generalist press, and it speaks well of Taniguchi's renown that such irregularities are even visible.

But that raises another question - what kind of renown are we talking about? The BBC prominently observed that Taniguchi's works were "widely praised for the gentle manner in which he approached subjects that were often unique for Japan's manga consumers," and "stood apart in a genre sometimes seen as rooted in extreme violence and pornography." Far be it from me to downplay the storied legacy of smut in Japanese comics, but framing Taniguchi as Manga's Good Boy does a disservice to both the breadth of his career and the facts of his publication history in English.

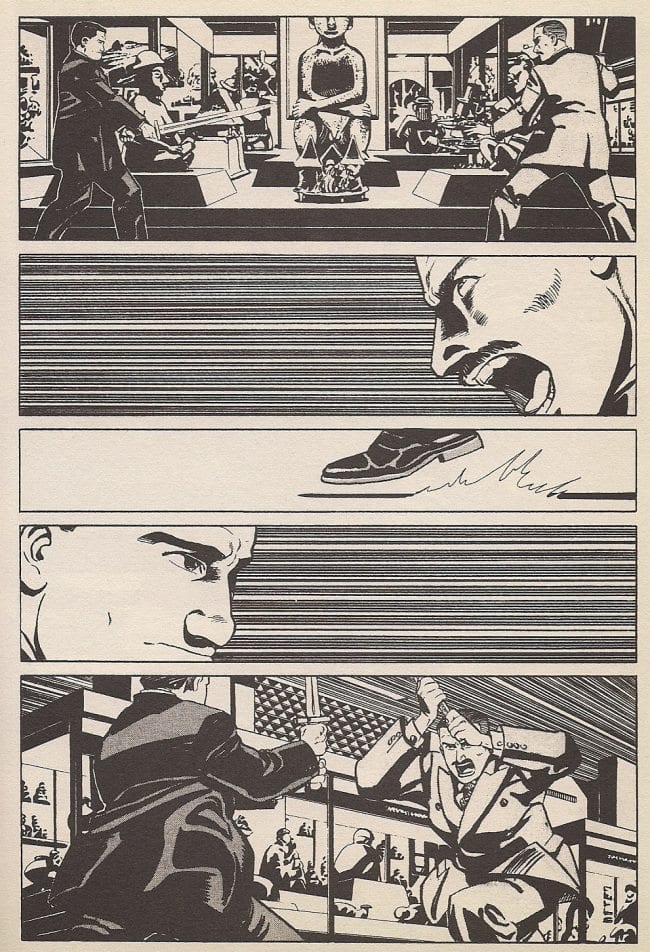

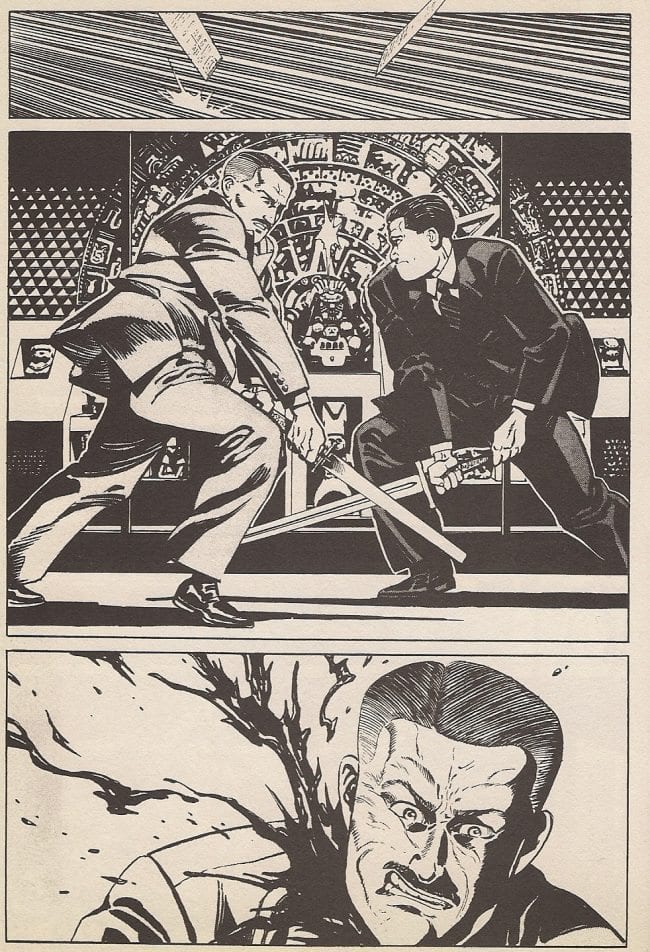

Indeed, extreme violence is where it all began, though the extremity was of an unexpected type. In 1990, VIZ debuted its "Spectrum" line of bookshelf-ready paperback originals, their dimensions matching those of popular softcover collected editions of American comic books. All of the works included in that line featured conspicuously detailed, laborious art (one supposes to flatter the tastes of local comic shop denizens, as was often the strategy in 20th century manga localization), but not all of them enjoyed the same success; nobody without a PhD in bullshit or the word "VIZ" on a tax return remembers Yu Kinutani's Shion: Blade of the Minstrel, but Hotel Harbour View, drawn by Taniguchi and written by Natsuo Sekikawa, became something of a cult favorite. I first heard about it on one of the British genre comic writer Warren Ellis' various message boards, deep in the midst of the 'decompression' trend in early-to-mid-'00s superhero comic books, but even those space-y, wide-paneled movies-on-paper had nothing on the climax to Taniguchi's & Sekikawa's title story, in which a fatal bullet is fired from a gun, only arriving at its target an extravagant thirteen panels later.

Even at *that* time such excess was startling; in 1990, it must have seemed nearly obscene, though the authors carefully contextualize their flamboyance as the event horizon of an anti-hero's worldview - he is a normal, cancer-stricken man who has hired an assassin to attack him while he engages in a private fantasy of life as a gangster; if he kills her, he will prove himself the idol he has dreamed of being, but even if he fails, a dramatic gunshot death will provide the perfect transubstantiation of noir role-playing into reality, blessing his otherwise unremarkable life with the only meaning he values: that of splashy, violent media.

Taniguchi had done quite a few comics of the full-contact type, including the long-running crime series Trouble Is My Business (also with Sekikawa, begun in 1979) and several gritty sports manga with future Old Boy writer Garon Tsuchiya, though the full scope of his career had already grown to include the dense, demanding historical-literary serial The Times of Botchan (once more with Sekikawa, begun in 1987). Nonetheless, Taniguchi's next appearance in English came via VIZ's Pulp, an anthology magazine aimed at mature readers, brimming with the sort of violent, sexy and somewhat art-damaged works that could only be enhanced by the addition of somebody who came up professionally around the same time as Katsuhiro Ōtomo and worked in a similar cartoon-realist meter. Benkei in New York may have come from a different writer (Jinpachi Mori), but its brooding and bloody assassination action was not wholly unlike that of Hotel Harbour View. A collected edition arrived in 2001, as the face of manga in English gradually began to change into something more youth-oriented and demographically egalitarian. Subsequent Taniguchi releases came from other publishers, and proved aberrational: Samurai Legend (CPM Manga, 2003), a minor historical adventure drama written by Kan Furuyama, and Icaro (iBooks, 2003-04), an allegorical SF collaboration severely distilled from a scenario by Jean "Moebius" Giraud & Jean Annestay that at least offered Taniguchi an opportunity to indulge his career-spanning affection for bandes dessinées.

French-language publishing loved him back. He'd been introduced to that audience in 1995, through a work far removed from bullet holes and sword fights - his masterpiece, The Walking Man.

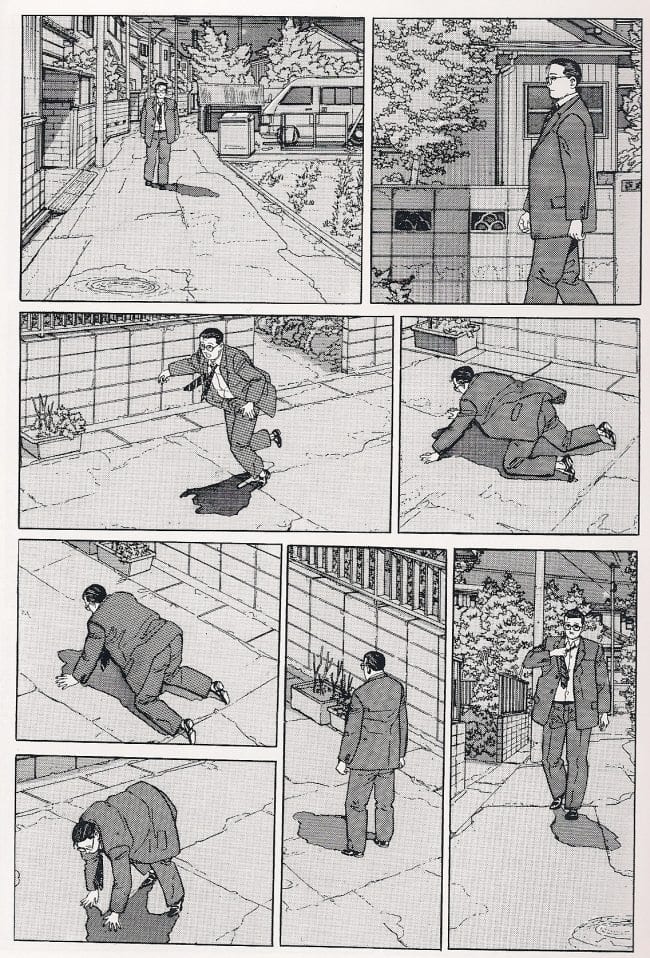

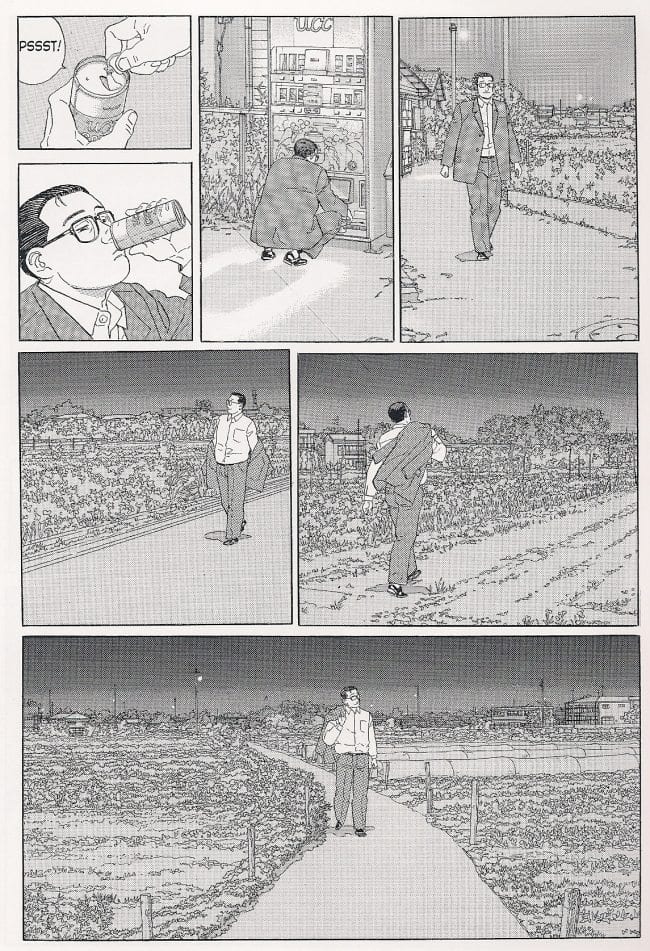

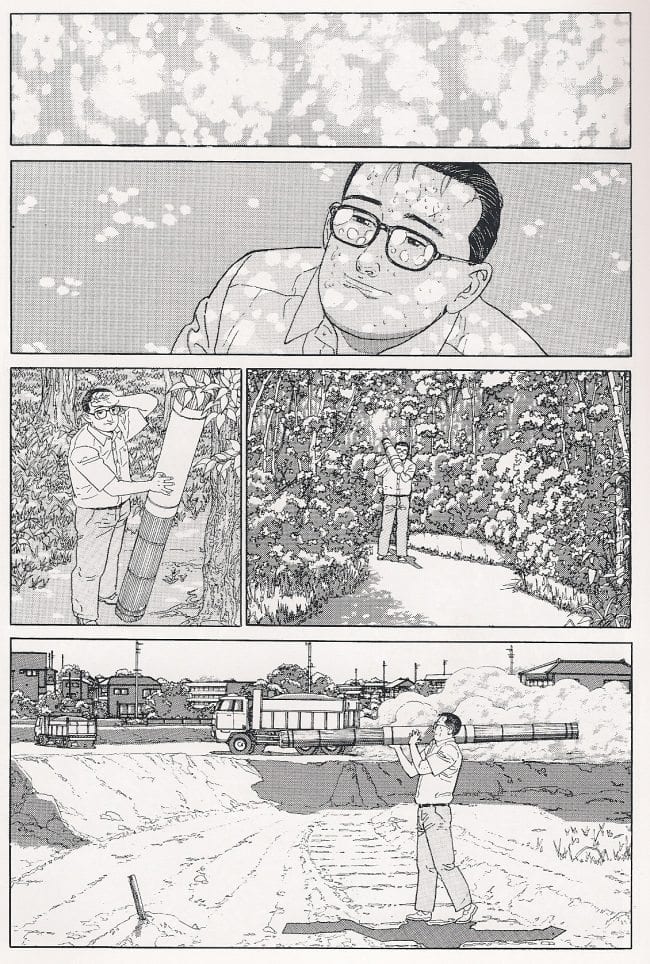

Introduced to English-dominant audiences in 2004 by the UK-Spanish publishing association Fanfare/Ponent Mon, The Walking Man marked the beginning of what is meant when Taniguchi-in-translation is described as "gentle" and "unique". There is really no 'plot' at all to the book, presenting instead a series of quiet vignettes in which a nameless man strolls around outdoors, taking in the sights. In truth, this stuff is not totally without peer in Japanese comics - not long afterward, there was a series that became very popular among aficionados of unofficially translated manga scans online: Hitoshi Ashinano's Yokohama Kaidashi Kikō (1994-2006), a soothing slice-of-life feature set in a fantastic world. A similar project, Kozue Amano's Aria, saw legit translation from ADV Manga the same year as The Walking Man.

At the same time, it would be a mistake to downplay the novel characteristics of Taniguchi's approach. This is not a science fantasy work, there are no impressive vistas of the speculative imagination to be found, and the protagonist is not an endearing young woman of the readily marketable type. Instead, it's a study of movement, place and gesture, wholly removed from ostensibly similar works of North American art comics at that time - the spare lyricism of John Porcellino, or the slashing marks of the Fort Thunder residents. This is an 'art' comic drawn with a crystalline certitude of realist space beyond that of even the most 'realism'-obsessed pop comic books in English; the result is something distinctly observational, as if you are literally standing next to the lead character and literally experiencing the outdoors alongside him, but only in the terrain of a dream, your POV shifting up close and away from his body, time dilating - the toolkit is the same used in that long gunshot from years ago, put to less bombastic but still formally perverse ends... at least by local standards. It is also like cinema, in the way Hotel Harbour View is 'like' the films of Melville, or the early Nouvelle Vague, though I have always found comics, by their unity of drawing, to be a more readily absorbing 'reality' than film, which sculpts time from the stuff of mechanical capture, and is thus endlessly discursive from the continuum of seeing. But maybe that's just me.

Of course, Taniguchi eventually enjoyed a movie version of his work in the west: Quartier lointain (2010), from Belgian director Sam Garbarski, adapting Taniguchi's series A Distant Neighborhood, released in French by Casterman, 2002-03 (Best Scenario winner at Angoulême 2003), and later in English by Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 2009. As luck would have it, by the time The Walking Man hit the market for bookshelf-ready comics had matured to the point where Taniguchi could become a viable brand, associated very closely with Fanfare/Ponent Mon, which would release fifteen books of his comics (not counting assorted reissues, a short story in the Japan as Viewed by 17 Creators anthology, or his grey tones on Frédéric Boilet's & Benoît Peeters' Tokyo is My Garden), ranging from the sensitive-macho silliness of The Quest for the Missing Girl (2010) to The Summit of the Gods (2009-15), a five-volume adaptation of a mountain climbing adventure novel by Baku Yumemakura. Nonetheless, it seems to be The Walking Man and A Distant Neighborhood that have controlled the tone of remembrances focused on Taniguchi the introspective dramatist.

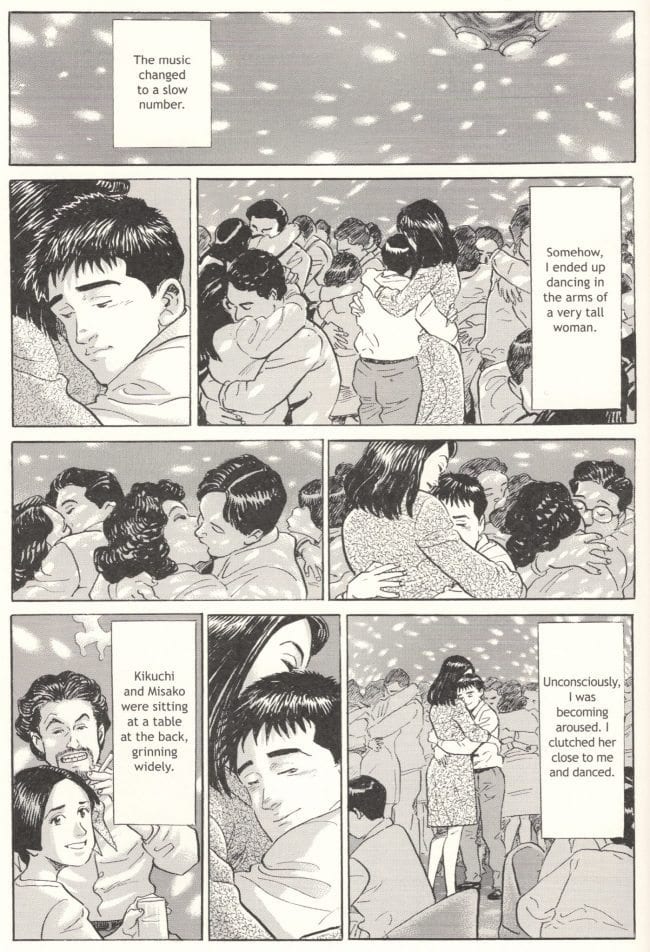

I am actually not so keen on his personal dramas; if made to choose, I would recommend A Zoo in Winter, a 2005-07 serial from the Japanese magazine Big Comic Original collected in English by Fanfare/Ponent Mon (at this point Taniguchi arch-specialists) in 2011. This at least, is set in the world of late-'60s popular manga, with Taniguchi drawing on his own apprenticeship to shōnen artist Kyūta Ishikawa for some keen observations as to the dynamics of a manga studio; there's also a great bit with the Taniguchi stand-in protagonist getting cornered at a bar by a revolutionary folk singer who won't shut the fuck up about the Marxist ninja cartoonist Sanpei Shirato that's far too keenly felt to not be a real incident.

It is grossly dewy and sentimental fare, though - packed with decent boys, roguish men with decent sides, decent men with roguish sides, and women who are alternately inscrutable and passionately dedicated, when not inspiring the protective impulse. Virtually every chapter involves a moment of empathetic realization worthy of a feel-good television movie, culminating in the full-throttle melodrama of a creativity-stoking gravely ill girl, and while I understand this is of great appeal to some (and perhaps of personal import to Taniguchi), I find it all awfully sodden and pat in execution. And even then, it is conceptually not so far removed from the prolific and studio-powered works of a veteran commercial mangaka like Kenshi Hirokane, specialist in salaryman soap opera and easily digestible human interest fare.

I only say this to offer a more rounded perspective on Taniguchi's career; he is in no way sui generis, though he is often superior. Always, his draftsmanship is very accomplished, and his visual narration as clean as can be. The Walking Man is undeniable, recommended with no hesitation, while Hotel Harbour View I consider a classic of its kind; maybe someday it'll come back in print, ideally with the 100 or so additional pages of stories from the Japanese edition. Hell, maybe Fanfare/Ponent Mon will finish releasing The Times of Botchan, which it began publishing in 2005, only to trail off following the fourth of ten volumes; I suspect there are deeper layers of Taniguchi's talent hidden within this collaboration, just as there are surely surprises scattered throughout the untranslated regions of his library, a far greater thing than we've had occasion to witness during his life.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday identified in the column title above. Be aware that some of these comics may be published by Fantagraphics Books, the entity which also administers the posting of this column, and that I also run a podcast with an employee of Nobrow Press. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting. You could always just buy nothing.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

My Favorite Thing is Monsters Vol. 1: I can only assume you've heard of this one, as Fantagraphics has been giving it a damned hard push. And why not? This 386-page debut graphic novel by Emil Ferris blends autobiography, murder mystery, wartime drama and classic monster movie tropes, all of it presented in the form of a young girl's notebook from the 1960s, its pulsing, bravura ultra-hatched color drawings created with ballpoint and felt-tipped pens. Adding to the book's mystique, its initial 2016 print run then found itself stranded on a cargo ship in the Panama Canal after the freight company fell into financial calamity - only now can this work be released for wide sales. Paul Tumey reviewed it in advance last year, and the author herself has recently put together a new introductory comic; $39.99.

Lovers in the Garden: Being the new comic from Anya Davidson, a 1970s-set urban drama in full color. That's really all I know about this 64-page Retrofit/Big Planet release, but Davidson is one of the most restless talents around today, and anything she releases is immediately of interest; $10.00.

--

PLUS!

Fires & Murmur (&) The Excavation: A pair of artistically-inclined comics from European-born artists, in a pretty packed week for foreign stuff. Fires & Murmur is a Dover hardcover compilation (or, rather, what appears to be an English-language adaptation of a 2010 Casterman compilation) of two albums by the great Lorenzo Mattotti: 1986's Fires and 1989's Murmur, the former a self-reflexive colonialist allegory swirling with incendiary color (first published in English by Catalan Communication in '87), the latter a dreamy amnesiac wander written by Jerry Kramsky (first published in English by Penguin in '93). This edition is 8.25" x 11", at 112 pages. The Excavation is the new one from Swedish artist Max Andersson, a longtime presence on the American alt-comics scene - indeed, portions of the book were originally presented in his millennial Death & Candy solo series. Weighing in at 382 pages(!), this 6.25" x 8.25" Fantagraphics hardcover promises nightmarish and surreal family drama 18 years in the making; $34.95 (Fires), $29.99 (Excavation).

Flight of the Raven (&) Snow Day: In contrast, here are two works of tony genre fiction from the French market. Flight of the Raven is the latest from IDW's Eurocomics line, a 2002-05 WWII adventure series from artist Jean-Pierre Gibrat, depicting a determined woman's participation in the French Resistance with extremely handsome realist gloss - the type of refined genre art that captured a lot of eyes in the '70s and '80s, when translations were less common and the grass often seemed greener. An 8.5" x 11" color softcover, 144 pages. Snow Day is a Humanoids release of a 2004 book from writer Pierre Wazem and artist Antoine Aubin, a low-key b&w crime drama set in a snowy locale. A 7.6" x 10.2", 112-page softcover; $29.99 (Raven), $14.95 (Snow Day).

Forever War #1 (of 6): Some of you might remember this one - not just the 1974 Joe Haldeman novel (depicting a man's travels through vast space and, as a result, time, all in the service of a massive, dubiously-premised war, Vietnam parallels not to be missed), but the 1988-89 comics adaptation drawn by Belgian artist Mark "Marvano" Van Oppem, released in English across the first half of the 1990s by NBM. Now Titan re-releases the project as a series of comic books, variant covers and all, in case you've missed it; $3.99.

The Can Opener's Daughter (&) Haddon Hall: When David Invented Bowie: And here's a duo from SelfMadeHero, the UK publisher distributed in North America by Abrams. The Can Opener's Daughter is a sequel to The Motherless Oven, a well-received 2014 book by artist Rob Davis. It's a dark fantasy of teen life and weird machines. Haddon Hall is a 2012 biographical album by Néjib, a Tunisian-born artist based in Paris. Doodled drawings and lysergic colors represent the early years of David Bowie, now available in English; $19.95 (Daughter), $22.95 (Haddon).

Starseeds: Can't say I'm familiar with the work of Mexico-based multimedia artist Charles Glaubitz, save for the fact that he's been exhibited by Monte Beauchamp of BLAB!, and he does seem to have the sort of molten pop-psychedelic style typified by works of that long-lived forum. Anyway, this 240-page, 7.5" x 10" color Fantagraphics hardcover is his first graphic novel, "a work of mythical, pictorial, illustrative, and cosmological components, while combining elements of myth, religion, and spirituality with comics, hermetic ideas, alchemy and science." Or, so says the publisher; $29.99.

Reich #1 (&) #3 (of 12) (&) Cerebus in Hell? #1 (of 4): A pair of possible-confusing indie comic book projects, each stemming from earlier work. Reich is a biographical project the artist Elijah Brubaker published through Sparkplug Comic Books starting in 2007; now Alternative Comics returns the series to comic book stores, in a somewhat mixed manner... issue #2 seems to have arrived last week, per Diamond's release list. Cerebus in Hell? is a jokey series Dave Sim has spun off from his long-lived self-publishing project in commemoration of its 40th anniversary, put together from clip art with latter-day production collaborator Sandeep Atwal as a set of gag strips. Still from Aardvark-Vanaheim, itself approaching its 40th birthday; $3.00 (Reich, per issue); $4.00 (Cerebus).

Umbra: Another one from Dover, this time collecting a 2006 miniseries from artist Mike Hawthorne and writer Stephen Murphy, the latter making a rare non-Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles-related appearance in comics subsequent to the stoppage of his signature series, The Puma Blues. I recall enjoying this in comic book form - a delve into secret global histories with action-adventure and bizarre science elements. Concise too at 144 pages, some of them devoted here to a newly expanded ending; $16.95.

The Wild Storm #1: Since I've mentioned Warren Ellis above (he was also involved with VIZ's Pulp magazine, albeit as a columnist), I should note that he remains active in comics, here as the frontman for the sort of thing you used to see more of in cape comics back in the '00s - full-blown revisions of certain superhero franchises, built around strong writerly perspectives. The subject matter here is the WildStorm line of comics founded by Jim Lee at the birth of Image and acquired by DC toward the end of the '90s; I believe the brand has been dormant for the better part of a decade now, so -- coupled with Ellis' own history with some of these characters, including Stormwatch and its megahit successor, The Authority -- there may be some pent-up demand. The art on this debut issue is by Jon Davis-Hunt (I've liked his muscular and bloody art on the 2000 AD werewolf fantasy serial "Age of the Wolf"), with Ivan Plascencia; $3.99.

100 Manga Artists: Finally, we return to Japan-by-way-of-Europe for your book-on-comics of the week. Originally released in 2004, the enormous Taschen art book Manga Design proved itself a genuine oddity - over 500 pages of seemingly random profiles of manga artists from across the post-war history of the form, many of them otherwise totally unfamiliar to western publication, accompanied by unusual and often rather obscure sample images. There was also a DVD of artist interviews, including a bit with Naoki Urasawa from well before more than a few hundred English readers knew who he was. Anyway, this is a smaller (5.7" x 7.9"), fatter (672-page), 'revised' edition of the original, apparently whittling down the profiles to only 100 and losing the DVD entirely. I've gotten lost in the original many times. Edited by Julius Wiedemann, with text in English, French and German; $19.99.