The year in which the three bottles are recovered is unknown. In fact, their receipt by the Oceanic Research Institute is a matter of chance; instructed to remit any bottle sealed with red wax in reference to a tidal research endeavor, the village counsel instead returns three notes, scrawled by hand.

The first bottle is a suicide note. Two young people have spotted the billowing white stacks of ships come to save them from a remote island, yet they whistle "more fearful than the trumpets of the Last Judgment." For their sins, their trespasses, the pair intend to throw themselves from a cliff in view of their parents, to be devoured by sharks.

The second bottle briefly summarizes the preceding angst of the notes' author, a boy, who was shipwrecked with his sister at a young age. The island provided for absolutely everything save for education, which the pair divined from a copy of the Holy Bible miraculously washed ashore with them. They grew healthy, alas, and began to desire one another's bodies, lacking otherwise in human consortium. "Please, I beg thee not to punish that virgin," begs the brother. "And yet, my Lord, whatever shall I do! How can I deliver myself from that torture!" He cannot kill himself yet. He burns the Bible, and then lays eyes upon his sister, praying, "[t]he divine beauty of a virgin," and sensing she may throw herself onto the rocks below, the brother seizes her as she flails and screams.

"And then, the two of us -- our bodies and souls -- were cast out into the murky depths of darkness, left to wail and regret our lot day and night. Not only were we incapable of holding each other tight to comfort and encourage ourselves, and pray and mour for our loss, we could not even lie down together to sleep." The island of bliss is now Hell itself, and the boy consigns the God-fearing hearts of him and his sister to a bottle's message, to preserve some witness of their purity under temptation's dawn.

The third bottle is written by young children. "Father, Mother. The two of us are good and getting along on this island. Please come to rescue us right away."

In the excellent 2013 anthology Three-Dimensional Reading: Stories of Time and Space in Japanese Modernist Fiction, 1911-1932, editor/translator Angela Yiu firmly implies that any English-language reading of Yumeno Kyūsaku's "Hell in a Bottle" (1928) is doomed to incompleteness. Japanese writing, after all, is logographic, and Kyūsaku employs three distinct styles in composing his very short story: (1) very dense, ornate kanbunchō to document the airless, bureaucratic discovery of the bottles; (2) a flowery blend of Japanese prose and Biblical language to convey the brother's matured writing style; and (3) basic katakana, as a child would draw, for the closing bottle's punctuation. "Typographically and visually," Yiu notes, "the story resembles a collage of different writing styles, a response to developments in modernist visual art in Japan and other parts of the world."

This was quite an irony for me; usually, I'm looking at Japanese comics which I can only read in pictorial terms. Now, I'm suddenly encountering prose I can discern, but lacking in any of the necessary pictures! Thankfully, I was able to combine both of these problems to form a perverse solution, courtesy of Japan's master of perversity: Suehiro Maruo, whose 2008 adaptation of Edogawa Ranpo's The Strange Tale of Panorama Island was released in English just last year to great acclaim. But in the interim, Maruo has released two books in Japanese: Caterpillar, another Rampo adaptation (also a film by fellow deviant Kōji Wakamatsu), and The Inferno in Bottles, a 2012 short story collection which derives its (English) title from an alternate translation of Kyūsaku's "Binzume no jigoku."

Immediately we have differences. While Yiu's "Hell in a Bottle" hones in on the angst of the penultimate note, the Maruo collection's "Inferno in Bottles" suggests a holistic perdition, and indeed Maruo's four included stories adopt wildly different tones, in parallel to the four narrative strains of the Kyūsaku tale. There's a Buñuelian comedy about a priest unable to cope with the vulgarity of the world; an EC/old-timey ero-guro-nansensu shocker about sexy young things plotting to rob a fat guy of the money he eats(!); and a story I frankly cannot understand without the aid of a translator, though it appears to reprise Maruo's favored theme of virtue abused, going all the way back to Mr. Arashi's Amazing Freak Show.

And then, of course, there's a comics adaptation of the Kyūsaku original, the prospect of which I think effectively splits the world of comics into two groups: those who've always wanted Suehiro Maruo's The Blue Lagoon, and those who don't yet know what they want.

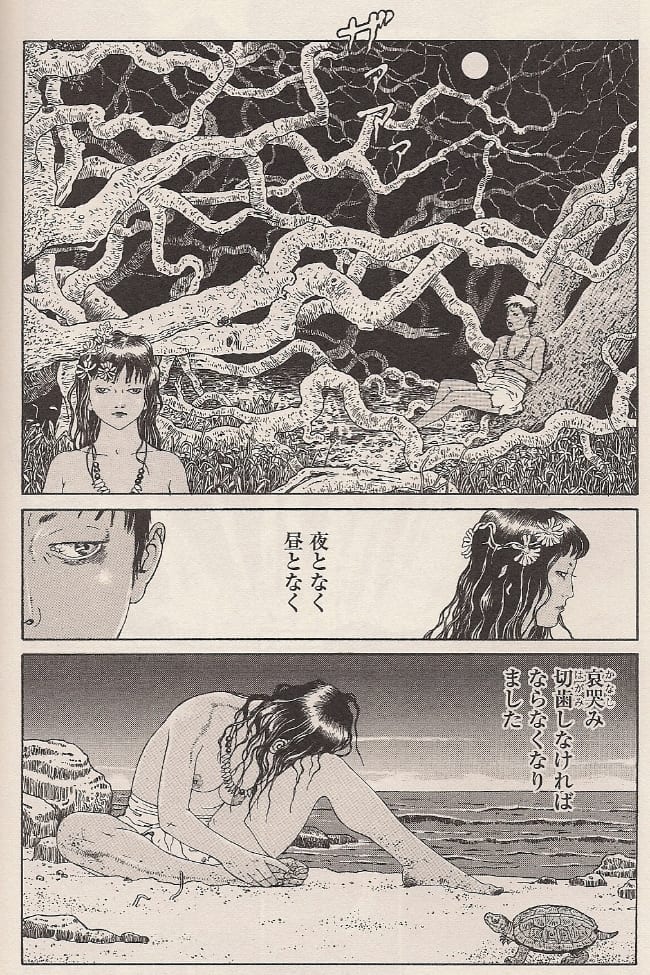

JESUS GOD. I try to avoid hyperbole in these columns, but the second panel on that second page above may be the most perfect depiction of lust I've seen in comics outside of the Robert Crumb oeuvre, and Maruo arguably does Crumb one better by communicating Kyūsaku's sense of equanimity; this may be a narrative of desire told from the male perspective, but the sin must be mutual to be truly enveloping.

Moreover, I suspect Maruo may be teasing a certain proclivity among Japanese media freaks; incest, or winking hints thereof, is a popular current trend/fetish among otaku (exemplified by the Oreimo franchise, the full title of which translates to "My Little Sister Can't Be This Cute"), and while Maruo hasn't historically paid that area of consumption so much mind, one might speculate that he or his editors at Comic Beam -- a magazine owned by the same company, Kadokawa, which publishes the resolutely geek-oriented Dengeki line of manga and light novels -- has happened upon a means of fusing his own fascination with early Shōwa period popular culture with a more contemporary brand of welcome shock: albeit in a puckish, condemnatory way.

As with Panorama Island, Maruo seems to approach the source material with a great deal of fidelity and respect; I am at the mercy of my linguistic shortcomings, but I will presume that Maruo's text is essentially the same as Kyūsaku's. Fans of Ultra-Gash Inferno may again be disappointed by the now-fiftysomething artist's relative gentility (though I hasten to add that such politeness still allows for the occasional erect penis). Moreover, while one might be tempted to expect some formalistic tricks from Maruo in response to the shifting texture of Kyūsaku's narration, his depictions remain uniformly his; unwavering in their heavy cartoon realism, which effectively flatten the subjective qualities of the original's voice with an outsider's dispassionate observations. Of course, I cannot imagine the "modernism" of Kyūsaku's narrative collage doesn't carry its own voyeuristic charge, so forcing us a ways further outside of the sinful duo is not inappropriate.

And anyway, Maruo has his own arsenal of techniques.

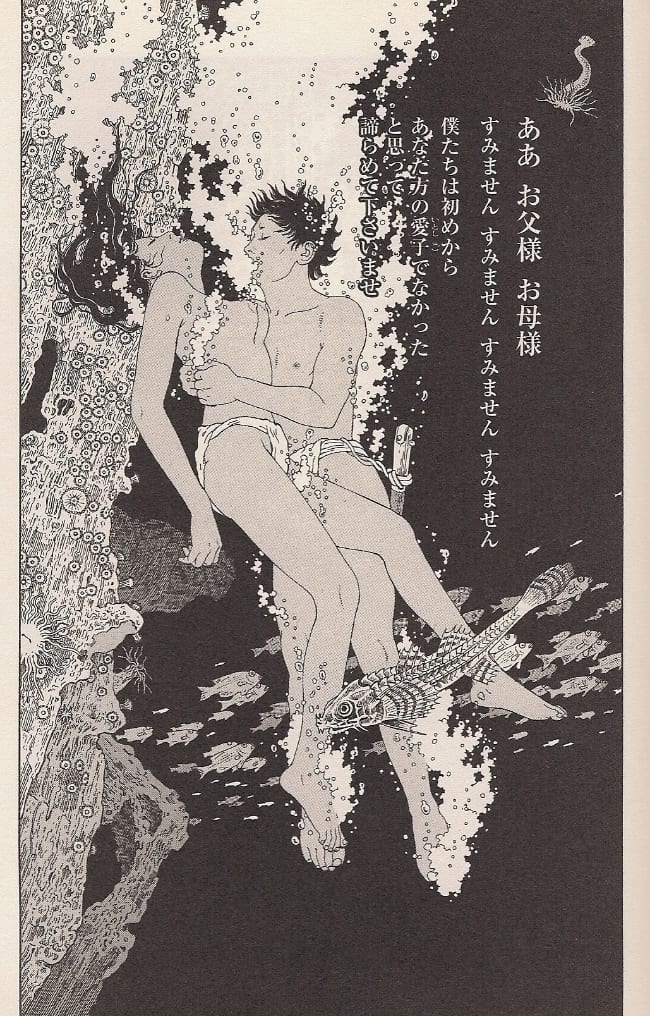

I have taken the above three images out of sequence; Maruo preserves Kyūsaku's disruption of chronology, i.e. showing the suicide first and then moving backwards (this attack on generic devices, Yiu notes, anticipates postwar Japanese authors like Kōbō Abe and Osamu Dazai, the latter's 1948 No Longer Human separately adapted to manga by Maruo fan Usamaru Furuya), but I have put them in chronological order, to best appreciate Maruo's usage of recurring composition. The first image depicts the siblings swimming nude and joyful, on the precipice of adult longings. The second rips them out of the water, as the brother 'rescues' the sister from suicide, perhaps only to ensure they die together; in Kyūsaku's text, this writhing physicality is the closest we get to witnessing the siblings' sexual consummation, and Maruo commemorates the occasion with an ejaculatory goosh of foam. And then: the suicide, which mirrors the composition of the earlier swimming lesson.

Through these subtle and wordless narrations, Maruo suggests a continuity of love between the two: a bodily affection, a physical proximity unaffected by the subjective pain of religious guilt. I didn't need Yiu to tell me that the island represents the Eden of Genesis, an allusion Maruo fully ascertains by cladding the siblings in loincloths after their healthy bodies have bitten, proverbially, from the fruit of knowledge of good and evil. They are ashamed of their nudity, but to be cast out of this paradise is to embrace oblivion.

At this point, you are no doubt wondering what all of this rather specifically Catholic, virginity-centered stuff is doing in a story from Japan, which had no exposure whatsoever to any form of Christianity until the 16th century, and remains among the most secular nations in the world. Kyūsaku had fervently studied Buddhism for a while, but ultimately abandoned the religious life for literature and theater, much to the chagrin of his politicized, Nationalist father: "Yumeno Kyūsaku" is a pen name, an insult the author's father slung at him, which Yiu roughly translates to "aimless dreamer." Obviously, Maruo's obsession with tracking atrocious behavior in the pre-war period would line up nicely with this context, and, truly, he cannot resist slipping in a little bit of himself.

This bitterly ironic image appears toward the end of the adaptation, denoting the opening of the third and final bottle, and the short narrative of the children. They are depicted in a highly posed, saccharine manner; I am no expert, but I suspect similar poses appeared in modern women's magazines from around the time of the original story's publication. The children are dressed with naval-style western accoutrement; such things became popular in the Meiji period, subsequent to the opening of Japan to the west. In this way, we might speculate that Maruo means to compare the Biblical upbringing of the children and their resultant sexual guilt to westernization itself, and a certain type of manga artist might gesture, then, to a pre-global time as favorable.

But there is a Sadean calculus to Maruo's work that hints at something deeper. I notice that the skin of the children darkens as they shuck off civilized attire and expose themselves to the sun; traditionally, fair skin has been prized in Japan, with lighter color suggesting a higher caste or economic privilege. To Maruo, these things are always lies; society is rot, and honesty can typically be found in the rejection of morality. This does not make people good, but it does make them honest; true virtue can exist too, but only to be exploited, abused, ruined.

The mechanics of Christianity, then, provide an auto-ruination for Kyūsaku's siblings. Through religious 'virtue,' they understand themselves as sinful, even as their rejection of everything desirable underscores their true, human yearnings. Maybe if they had just embraced their place as rutting wild animals, they would know happiness. Maybe that is the only happiness Maruo is apt to embrace.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday identified in the column title above. Be aware that some of these comics may be published by Fantagraphics Books, the entity which also administers the posting of this column. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

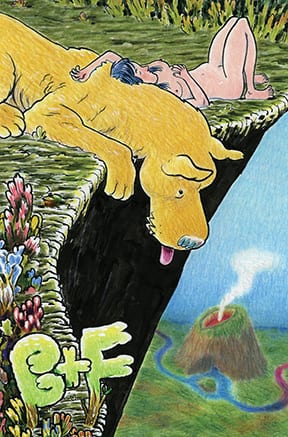

B+F: Gregory Benton is one of those artists who've been around for years -- decades actually; SLG released his comic Hummingbird back in '96 -- and then suddenly rise to prominence; Brandon Graham is another. In Benton's case, the enthusiasm centers around this 10" x 15" AdHouse/Éditions çà et là release of a 64-page wordless color fable, a "meditation on goodwill, hostility, and isolation" involving a naked lady and a gigantic dog. The book spent much of 2013 as an unusually recurrent 'what the fuck look at that' presence at alternative comics shows (a 20-page self-published predecessor dropped at MoCCA back in April), and now it's available at all the better Diamond-serviced retailers. Preview; $19.95.

Minimum Wage #1: And in keeping with the '90s theme, here is a new revival of Bob Fingerman's slice-of-life series, published for a while by Fantagraphics in various forms before Image released a gigantic compendium in 2013. That same company will be facilitating this ongoing series, which will see monthly six-issue bursts separated by hiatuses, a la the various Mike Mignola properties over at Dark Horse. Expect new and old characters, and lots of uncomfortable humor. Preview-interview; $3.50.

--

PLUS!

Prison Pit: Book 5: Hey, it's Johnny Ryan, with the latest 120-page installment of his ultra-violence fight comic/study of bodies in flux. I think an animated webseries is still forthcoming, though I'm not sure if Ryan still plans to end the series with the next volume; minds change often. Preview; $12.99.

2000 AD Presents: Sci-Fi Thrillers: If you happen to follow Judge Dredd Megazine, you know every issue comes with a smaller comic reprinting whole or partial storylines from earlier issues of 2000 AD and related magazines - usually stuff too weird or short to warrant a separate collection. Well, now Rebellion's got you a 320-page brick of basically that kind of stuff, grouped around the exceedingly broad theme of "Sci-Fi" (I mean, given the forum). Highlights should include the entirety of a 1988 Peter Milligan/Tony Wright serial, Tribal Memories -- which I understand should appeal to fans of Milligan's work with Brendan McCarthy -- and the 1978 Pat Mills-written joint The Visible Man, concerning a fellow whose skin becomes translucent. There's newer stuff too, like XTNCT, a Paul Cornell/D'Israeli dinosaur evolution serial from 2003-04. A lot of this stuff *has* been reprinted before, mind you, but finding them is now a lot easier. Samples; $31.00.

The Complete Multiple Warheads Vol. 1: Last year, Image released Multiple Warheads: Down Fall, a compilation of early stories concerning the aforementioned Brandon Graham's continuing solo project, a spread-out wander through jokes and affections in a fantasy zone. That, I think, was a service to comic book collectors, because here, now, is a 208-page collection of all applicable content Graham has released to the present, including the 2012-13 Alphabet to Infinity series; $17.99.

Wandering Son Vol. 6: You know what else was published in Comic Beam? Shimura Takako's gentle story of gender identity among middle-schoolers, which concluded its serialization back in August for 15 collected volumes in sum. Fantagraphics, meanwhile, offers 220 more pages here of Matt Thorn's translation in a no-doubt attractive hardcover. Preview; $24.99.

Manga Classic Readers: Ulysses: I guess some people thought I was just straight-on making fun of Comic Shop News last week, but let me assure you, I seriously did find a number of interesting items in their own shopping list. I mean - come on! One Peace Books is getting an entire line of Japanese comics adaptations of western literature distributed to comic book stores on Wednesday, but it's this one -- a 384-page transubstantiation of James Joyce's modernist bellwether into the plainest set of manga devices that "Variety Art Works" can collectively muster -- that promises if not a cockeyed insight into the (potentially bishonen) male relationships of the original, than at least a long-burning log of publishing camp along the lines of that Anne Frank biography involving Astro Boy. I won't say don't miss it, but DON'T. Preview; $9.95.

Smuggler: One Peace (that name!) is also doling out some reissues from defunct publishers' back stock this week, and I think the most eye-catching of those would have to be this 376-page Shohei Manabe seinen crime comic, which Tokyopop released years ago along with the same artist's grim urban fantasy serial Dead End. I don't think he's been seen in English since, but don't cry too hard - Manabe's current series, Ushijima the Loan Shark, just saw the release of its 29th collected volume this past November, in anticipation of both television *and* movie adaptations (neither its first) later this year; $14.95.

Journey by Starlight: A Time Traveler's Guide to Life, the Universe, and Everything: But One Peace doesn't just publish Japanese stuff - this, for instance, appears to be an educational comic of the sort that's managed to gain a foothold among larger book publishers. The writer, Ian Flitcroft, is a novelist and eye surgeon(!!) who runs a blog of the same title. Topics include "relativity, black holes, quantum mechanics (for beginners), climate change, evolution vs. intelligent design, and how the brain works." I like the look of the artist, Britt Spencer, whom I believe is an illustrator for magazines and children's books. Official site; $18.95.

Adventure Time Flip Side #1: So, while I was looking at Japanese comics I cannot read and/or neglecting to put the shopping list portion of my column into publishable enough shape so that a server burp wouldn't delay it for 21 hours, a whole bunch of small, popular movements continued apace. BOOM!'s line of Adventure Time tie-in comics continued to be a huge thing (as far as all-ages fare goes), and MonkeyBrain Comics continued to garner a certain unusual degree of attention for non-free digital-first comics offerings. And now the two sorta combine, as MonkeyBrain's top team, Paul Tobin & Colleen Coover (of Bandette), write an Adventure Time spin-off of their very own, with art by one Wook Jin Clark. Preview; $3.99.

Shaolin Cowboy Vol. 2 #4 (of 4): Concluding Geof Darrow's latest action comics experiment, nearly 1/2 the length of which has been spent observing the title character wordlessly chopping zombies to pieces from a fixed, pivoting POV in uniform wide panels. In this issue, he uses his fists. Preview; $3.99.

Detective Comics #27: Ha ha ha, oh my gosh, you see - Batman first appeared in Detective Comics #27 in 1939, but now DC has restarted all of their series from #1, so this is the new Detective Comics #27!! Basically, it's an excuse for a whole lot of past-and-present Bat-contributors to take a crack at what is now what the X-Men franchise was in the '90s. Frontman Scott Snyder is present (with Sean Murphy, his collaborator on Vertigo's The Wake), along with Neal Adams (drawing from a Gregg Hurwitz script), and even Frank Miller, who contributes a variant cover. Also, Brad Meltzer will apparently be writing an updated version of the origin story, if that's your thing. Samples; $7.99.

All New Marvel NOW! Point One #1: I don't even want to consider the possibility that this is supposed to be a new reader engagement sampler, given that the title is difficult to even say, let alone understand, but these things are nonetheless worth flipping through because sometimes a few off-kilter talents will get a short story. For example, Steve Pugh(!) should be drawing part of this, along with the more Marvel-traveled Mike Allred. Preview; $5.99.

Lament of the Lost Moors Vol. 1 (of 4): Siobhán: Your Cinebook pick of the week (they put out a LOT of stuff), as the very skilled Thorgal artist Grzegorz Rosiński teams with veteran Belgian pop comics writer Jean Dufaux for a 1993-98 series exploring sorcery and sword-swingin' in a Celtic setting. Note that Defaux began a sequel series in 2008 with Philippe Delaby as artist. A 7.24" x 10.12" softcover, running 64 pages - note that Cinebook has scrubbed nudity from their localizations in the past. Preview; $15.95.

Heavy Metal #266: And finally, here is the oldest Eurocomics forum still existing in English, now up to part 5 of their scattered, irregular translation of Enki Bilal's 2009 Animal'Z. Other stuff too, like a short comic by Tayyar Ozkan of the old Paradox Press crime comic La Pacifica, but really - only one choice at the moment for new-ish Bilal in English; $7.95.