This past week saw the 2013 edition of Leeds' Thought Bubble Festival come and go, and with it my resentment over a chronic inability to attend excellent-looking comics shows in foreign locales that nonetheless know a lot of English. No Tintin, Boy Reporter am I. Still, many opportunities arose to live vicariously, among them a photo-laden post by Sarah McIntyre, which caught my interest through its coverage of the British Comics Awards' Young People's Comic Award - apparently handed out in front of a horde of uniformed schoolchildren! I only ever see classrooms of local kids touring the farm show among the events on my convention calendar (the food's great) so the community-mindedness of Thought Bubble is a great inspiration.

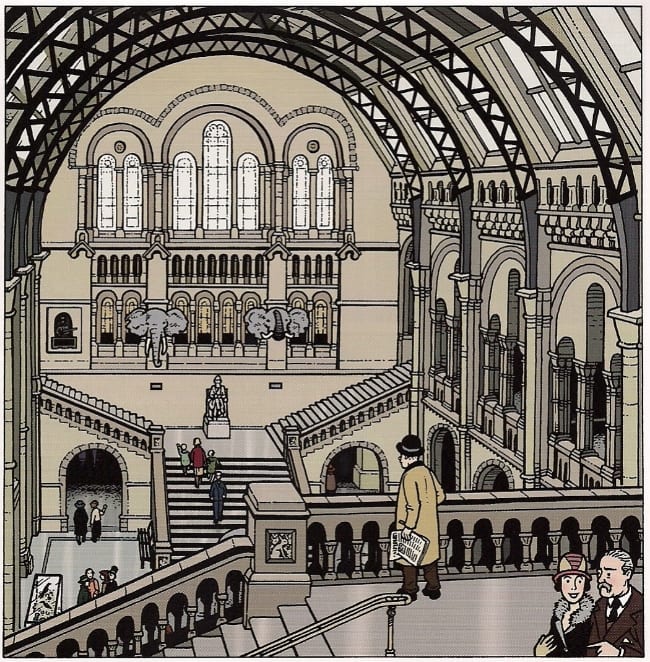

Plus, I'd actually read the winning book: The Complete Rainbow Orchid by Garen Ewing, a glossy evocation of mid-20th century Belgian bande dessinée, as wedded to the ripping yarns of H. Rider Haggard and the golden age of silent movie comedy. North American iPad owners can purchase the book through the Sequential app, although no such print publisher has picked the material up for distribution; you'll have to import Egmont UK's 9" x 12" softcover album, or any of the three component albums which the same publisher has been releasing since 2009, though the origins of the work date back to 1997, with magazine serialization, self-publication and webcomic avenues duly explored. To outside observers, it may seem the classic overnight success of 15 years' making, though I know Ewing had also been active in the UK fanzine and small press scenes for a while.

I first learned about The Rainbow Orchid though Forbidden Planet's terrifying suite of Best of 2012 lists, though my appetite was really whetted by learning about the artist's influences; no simple Hergé devotee, Ewing counts Edgar P. Jacobs as a crucial motivator, while also maintaining a keen interest in Yves Chaland, one of my own personal favorites. It was Chaland, in fact, which raised certain expectations about the work - perhaps unfairly, in retrospect.

You see, while The Rainbow Orchid is published by a prominent purveyor of children's comics (Tintin among them), its origins suggest a less distinct audience; indeed, Ewing himself has mentioned not particularly seeing it as "a children's book." However, it doubtlessly draws some inspiration from the children's comics of the mid-20th century, as did the work of Chaland, who both wrote about those comics in Métal Hurlant and created his own comics as both evocations and 'responses' to the content of that era. His was a manic-depressive fandom, the Freddy Lombard albums he created for Magic Strip and Les Humanoïdes Associés evoking by their very title Le Lombard, the Belgian comics publisher built on the back of Le journal de Tintin, but also standing as works of interrogation and parody: The Elephant Graveyard, for example, deliberately aggravates the racist and colonialist attitudes espoused by works of the time.

As a result, I found myself searching for hints of "Chaland" in Ewing's book, not simply in visual terms but through the expectation that the setting of the tale -- England and colonial India in the 1920s -- would not simply exist as a flat locale, but as a means of commentary or reflection. After all, the simplicities afforded an author by an audience of children (or a desire to create a work simply in the mode of something aimed at children) do not foreclose on the messages such works can deliver through their posture: that non-white, foreign people, for example, require white intervention to save them from their ignorance. Creating a work which merely presents such things as background, as a matter of homage, then, risks promulgating an identical message, especially when a publisher decides that hey - let's sell it like a children's book after all!

Now, truth be told, even in its decoration, The Rainbow Orchid is assiduous at avoiding offense. Almost every foreign land's horde of scary thugs is noticeably mixed in terms of ethnicity, except when the thugs are understandably upset at the things the white heroes are doing. This even leads to the occasional absurdity - above we see a black supporting character comically failing to infiltrate a secret society ("[p]eople of influence mixed with people from the gutter," sniffs a not altogether sympathetic civilian), in which nobody takes any particular note of his skin color, which would almost certainly be quite a convincing spoiler otherwise. In this way, there is an idealization to the comic that edges close to advocating warm, harmonious memories of Indians content to peaceably serve the British Raj, and what a time it was when young people could travel to such thrilling new places and encounter folks in charge who are just like them.

That said, I don't think Ewing falls into any such traps. In fact, while he obviously plays it soft and smooth, I detect a certain class consciousness behind the comic. Young hero Julius Chancer is the runaway son of a farmer, whose exploits in the Great War do not merit his acceptance into the higher echelons of British government; instead, it's only when his adoptive-ish father-y figure Sir Alfred Catesby-Grey severs relations with the Crown (he's a pacifist, into research for the good of knowledge itself) that Julius enjoys some liberty to go off on adventures after lost treasures. The heroine, Lily Lawrence, meanwhile, is a rich girl who flees home to become an actress (in the very low-class, new-money world of American cinema!), while her irresponsible comedy alcoholic father gambles away their noble birthright to a scheming businessman in a manner which -- through several unlikely twists -- requires Julius 'n pals to go searching for a rare, possibly mythical flower. In this way, the book's scenario is both 'status quo' enough to remove one's breath -- they're on an adventure to save an aristocrat's estate from a rapacious interloper, for Pete's sake! -- yet entirely cognizant that the whole affair is balanced on authority figures acting like morons, inadvertently midwifing the agency of the younger characters.

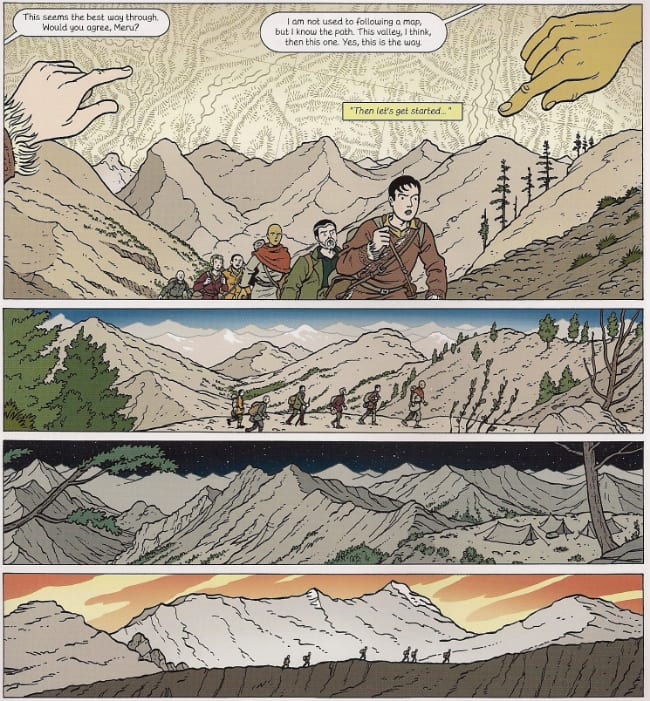

Again, this is all conveyed quietly enough so as not to disrupt the immediate appeal of adventuresome, Lost Civilization-type throwback stuff, but it's there. Maybe the most direct comparison is Hergé after all, but the older man who created Tintin in Tibet - essentially, it is a work emphasizing personal understanding among humans. Eventually, Julius and the gang hook up with Meru, the seeming retainer of an impossibly aged missionary but actually a controversial figure in the mythic city of Urvatja, home of the Rainbow Orchid, which is actually a profound religious artifact. What follows is the most interesting page of the book.

It is a fantasy language these people speak (though a bit of authentic Kalasha is heard elsewhere), but what's important is that the 'main' cast are kept entirely out of primacy, and the indigenous people are allowed to voice themselves in a manner which makes no effort to include the Anglo heroes' attention. They are not the center of the universe, it turns out; the sun will set on them. And when push comes to shove, they finally understand these people enough to leave their culture behind without disruption, and respect their autonomy as individuals.

And if the legacy of colonialism was and is a great fascination for Chaland and other European artists (see also the upcoming Arsene Schrauwen), we can see this conclusion as Ewing's contribution to the style, most resonant among his book's prolonged chain of rather open-ended codas, all but begging the fates to allow a sequel or two. I cannot say this is a work which stands with the best of the mid-century greats -- the slapstick is too laborious, the plot a bit crowded and bulky, and the character personalities never as instantly connective as the most memorable personalities of the old books -- but few of those artists were masters in their first few albums anyway. Here's hoping that an award will encourage more and better journeys.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday identified in the column title above. Be aware that some of these comics may be published by Fantagraphics Books, the entity which also administers the posting of this column. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

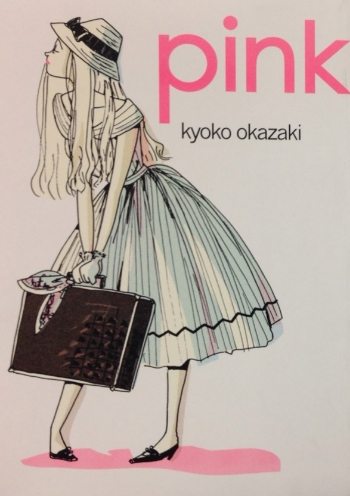

Pink: I've been hearing a lot of nice reactions from out in the wider comics sphere about Vertical's release of Kyoko Okazaki's Helter Skelter from a few months back, so maybe some groundswell of hype will build to elevate this considerably older work, a 1989 serial which confirmed its author's place as a standard-bearer for the new wave of comics aimed at adult women. It's about an office lady who's a prostitute, a middle-aged women sleeping with a younger man, and a novelist determined to relate everything back to himself - a portrait of a nation floundering in economic prosperity is purportedly formed. It'd probably be a good idea to pursue this one if you're into this area of comics, since Vertical is one of the few reliable purveyors, and they tend to give individual authors only a short time to demonstrate their sales viability; $16.95.

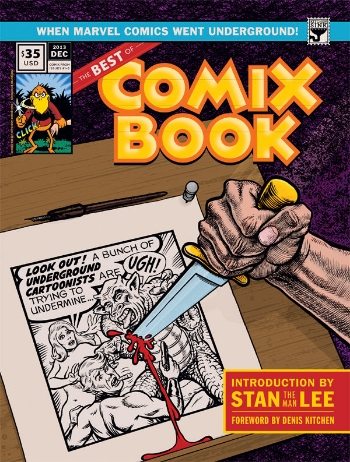

The Best of Comix Book: When Marvel Went Underground: It was the late underground period. The field was crowded. Head shops were closing and obscenity standards were diffuse. And yet, a strange counter-mainstream was building on newsstands, where b&w magazine publishers like Warren and Skywald were struggling with established publishers like Marvel for rack space, free of the restrictions of the comics code. In the midst of all this, Stan Lee hooked up with Denis Kitchen for an experiment in publishing certain less-than-extreme 'underground' comics via these permissive mainstream means; Warren's own Help!, after all, had offered young artists like Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton early exposure in the prior decade. The experiment was not a success -- after three issues, the title reverted to Kitchen's own Kitchen Sink Press to burn off accumulated materials -- and the effort quickly became overshadowed among connoisseurs by the arrival of the last great underground-period anthology, Arcade. Still, I'm sure some interest can be found in a selection of the better parts of the endeavor, which is exactly what Dark Horse is publishing in this John Lind-edited 184-page hardcover, with new text inclusions by Lee, Kitchen and James Vance. Contributors include Kitchen himself, Justin Green, Skip Williamson, Kim Deitch, Trina Robbins, Harvey Pekar, S. Clay Wilson and Art Spiegelman (offering up an early iteration of the eternally debatable Maus). Preview; $35.00.

--

PLUS!

Kafka: The Castle: This looks to be at least the *third* Franz Kafka comics adaptation(-ish thing) to count scholar David Zane Mairowitz among the creative team - he also worked with Robert Crumb on Introducing Kafka and Chantal Montellier on Franz Kafka’s The Trial: A Graphic Novel. Now the publisher of the latter, SelfMadeHero (via North American distributor Abrams), presents another adaptation, this time with art by Czech artist Jaromír Švejdík (aka: Jaromír 99), working in a curling, high-contrast style reminiscent to me of Seth Tobocman, though maybe some of you have seen Alois Nebl, a movie adapted from comics he illustrated a few years back. A 144-page softcover, 6.5" x 9.5". Samples; $19.95.

The Fantastic Voyage of Lady Rozenbilt: At this point, Humanoids has released enough material by creators otherwise unfamiliar to North American readers that they're cultivating little worlds of continuity. Hence, this near-simultaneous release with Les Humanoïdes in France, an 8.5" x 11", 124-page hardcover standalone spinoff of District 14, an Angoulême prize-winning series by Pierre Gabus & Romuald Reutimann which Humanoids translated the first "season" of earlier this year. Per the writer, the scenario involves "a millionaire who isn’t exactly unpleasant but who is extremely indulgent, extravagantly pleasing herself, her despicable nephew, and her guests (who aren’t always as interesting as they’d like to think they are)." Human and funny animal characters combine, with some monsters, it appears. Looks attractive. Preview; $29.95.

Barracuda Vol. 1: Slaves: On that note, coming from the UK, Cinebook has its own slew of translated releases, including the 7.25" x 10", 56-page start of this piracy-themed series from writer Jean Dufaux (whose series Raptors and Dixie Road you may remember with NBM about a decade back) and artist Jérémy, which just saw its fourth volume released on the continent last week. Preview; $13.95.

Polar: Came from the Cold: The obligatory 'I don't know anything about this comic' selection for the week, a Dark Horse collection of an espionage webcomic by Spanish artist Victor Santos, which made me say "whoa" out loud when I clicked on the latest digital page, so that's something right there. Jim Steranko, Jose Muñoz, Alberto Breccia, Alex Toth and Frank Miller are among the cited influences, which sounds like as good a crew as any for genre stuff of this sort. Give it a look? Preview; $17.99.

Life Begins at Incorporation: Cartoons and Essays by Matt Bors: But one thing we can all agree on as citizens of the world is that political cartooning can be quite the irritant to established powers, and few today are more prominent in the U.S. among comics-savvy tragics than Bors. This is a Kickstarter-funded 240-page color collection of strips and texts, which was made available digitally and on the artist's website a while back, but now is distributed to comic book stores under the auspices of Top Shelf. Samples; $20.00.

Yotsuba&! Vol. 12: Has very much attention been paid to crazy-popular manga series that hit the limit of how much material is available to translate, forcing them to fall back on Japanese release schedules without the benefit of (legal) exposure to serialized chapters, or really any potential of their artists remaining in the public eye? Like, do these series maintain very much of their audience? I dunno, it just seems like forever since we've gotten any new Kiyohiko Azuma, but - of course not, it's a monthly series. Anyway, I'm sure Yen Press is confident in the lasting appeal of this ongoing slice-of-life comedy about a cheery little girl having fun, one of relatively few examples of this otaku-born type to cross over into lucrative YA territory, or so I understand. Parents of little kids probably won't just pirate the newest chapters either; $12.00.

Crayon Shinchan Vols. 1-3: And waaaay on the other end of appeal, here is a tall stack of 360-page 3-in-1 omnibus compilations for Yoshito Usui's gleefully unsophisticated toddler, an irregular presence on the North American scene for almost a decade from multiple publishers (including, at one point, DC's manga division), to say nothing of the popular anime adaptation. This time it's the never-not-hilariously-named One Peace Books doing the honors, although I don't think the translation is new. Note that these books have been available through various channels since last year, with Diamond only distributing them to comics stores now, perhaps in anticipation of a newer vol. 4's imminent arrival; $12.95 (each).

The Smurfs Anthology Vol. 2: The newest in NBM/Papercutz's line of adult-targeted 9" x 11" hardcovers collecting the works of one Pierre Culliford, notable for reprinting a 1959 Johan and Peewit album ("The War of the 7 Springs") which has never been released in English. Otherwise, it's chronological Schtroumpfs, including the debut of Smurfette, all written with the redoubtable Yvan Delporte; $19.99.

The Shadow 1941: Hitler's Astrologer: Oh man, here's an artifact - while the Shadow is typically associated with DC in the mid-'80s, re: an increasingly weird series of comics by Howard Chaykin, Andy Helfer, Bill Sienkiewicz and Kyle Baker, there was also a throwback version of the same character published at around the same time as a Marvel Graphic Novel, reuniting DC's own 1970s Shadow team of Dennis O'Neil & Michael Wm. Kaluta, with the addition of Russ Heath as inker. Now Dynamite reprints the whole thing as a hardcover for those of the old school who don't want to look for an original copy. Handsome, this. Samples; $19.99.

The Maxx: Maxximized #1: Ah yes, who can forget that day in early 1993 when we all stood in the local comic book store, jonesing for more Shadowhawk, scanning the new release spinner, the crack of fresh spines ringing in our ears, finally settling upon some weird-looking thing with a purple platypus crouching in front of a blood-spatter sun? Now you can re-live the magic through this IDW reissue of Sam Kieth's original '93-98 series -- a unique fusion of surreal mental voyaging, sardonic interpersonal drama and claw-handed bloodletting of the Ingratiating Image Initiative -- re-scanned from the original art with revised coloring by Ronda Pattison. William Messner-Loebs co-writes, with Jim Sinclair on inks; $3.99.

The Sandman: Overture Special Edition #1 (of 6): Kieth, of course, is also co-creator of this endlessly (HA GET IT) profitable Vertigo enterprise, and it was pleasant as always seeing his name in the credits. But the artist of this particular series is J.H. Williams III, and while I know we all sort of roll our eyes at Special Edition releases of individual comic books as blatant stopgap maneuvers (issue #2 won't be arriving until February), it'll probably be kind of neat seeing Williams' art in varying stages of completion, including (if I'm reading the solicitation correctly) some preliminary colors prepared for (one imagines) the benefit of official colorist Dave Stewart. Williams will also be interviewed at some point in this 42 pages; $5.99.

Drawing from Life: Memory and Subjectivity in Comics Art: And finally - what better way for a red-blooded U.S. patriot to settle in after a long fight with a bird than with the latest scholarly tome from the University Press of Mississippi, this time a 272-page hardcover anthology of essays on "autobiography, semiautobiography, fictionalized autobiography, memory, and self-narration in sequential art," edited by Jane Tolmie? I am assured Martin Vaughn-James is among the artists considered, with contributors including Isaac Cates and David M. Ball. Impress everyone in line for consumer goods with your thoughtfulness and erudition, and tell 'em I sent ya (to pick up my new blender); $60.00.