When I was young, the first among my political assumptions was that the shift in governance from one Congress or one executive to another was in effect to glance at the obverse of a heavy and rugged coin; America, regardless of leadership, had a quality of lasting metal that would not bend in terms of what I would see if walking down the street. My life would not change. There would be school, of course, and open shops, and the closed circuit of family and community, upset only by certain death - and death, fundamentally, was an act of God.

My great mistake was in accepting this assumption as an aspect of the American character, rather than an apparition born of the particulars of my birth: class; gender; race.

Not a few months ago, at the Cartoon Crossroads Columbus festival, it was my great pleasure to meet La Morris Richmond; he was present for SÕL-CON: The Brown + Black Comix Expo, a suite of events partnered with CXC and run concurrently in the same venues. I've written about Richmond's work before, specifically the 1993 Northstar horror comic Boots of the Oppressor, one of the most potent among b&w indie shock-horror specimens for its detailed attention to the systemic and linguistic dehumanization of black men and women under slavery. It is probably still Richmond's most visible work, coming half a decade after his comics debut in NOW Comics' The Real Ghostbusters #4, pencilled by a young Evan Dorkin; a rather gentler style of horror.

Indeed, there were not a few black creators active in the '90s indie horror comics scene and its adjacent 'bad girl' boom of sexy occult divas. The late Steven Hughes springs to mind; he was co-creator of Evil Ernie and Lady Death, titles most commonly associated with their writer, Brian Pulido. The artist Louis Small Jr. was also prominent, having overseen the revival of Vampirella with writer Kurt Busiek and inker Jim Balent. But Richmond's works as a writer were much spikier, and far less common - he only published one other short story with Northstar, the almost oneirically scattershot ".12 Gauge Solution" in Splatter Annual #1 (1994, drawn by Rich Longmore), before embarking on a work ostensibly more populist yet pushed even deeper into intensity - scenes from the life of a black separatist superhero.

Jigaboo Devil #0 was released in 1996 by Millennium Publications, an outfit most readily associated with licensed and literary-driven titles in the pulp and horror vein (Anne Rice, H.P. Lovecraft, Doc Savage), though it would eventually release some early works by Dean Haspiel and Josh Neufeld. The comic was advertised as a four-issue miniseries, though only the 32-page #0 seems to have been actually printed at that time; enough art was produced for at least one more issue, and today a 96-page iteration of the story is available digitally or print-on-demand. Three pencillers are present: Barton McGee, an illustrator and caricaturist who doesn't look to have ever drawn another published comic book again; Andrew Kudelka, a Northstar veteran with some superhero credits who would later work in gaming art; and Jiba Molei Anderson, a debutante artist who, in 1999, would found Griot Enterprises, an indie genre comics outfit that currently handles the book's publication. The inker was Seitu Heyden, artist of the long-running Peace Corps drama Tales from the Heart, and the letterer was black fanzine and underground comics pioneer Grass Green.

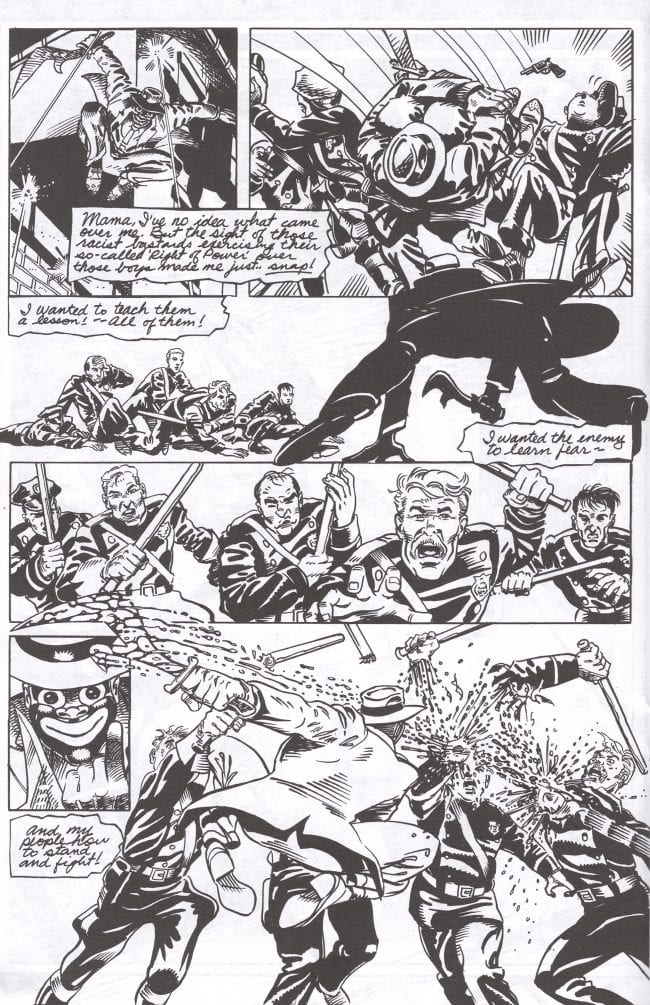

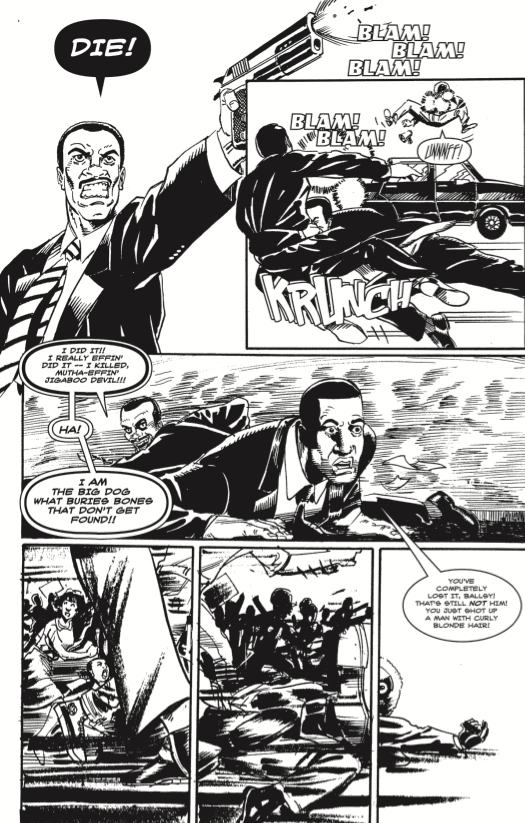

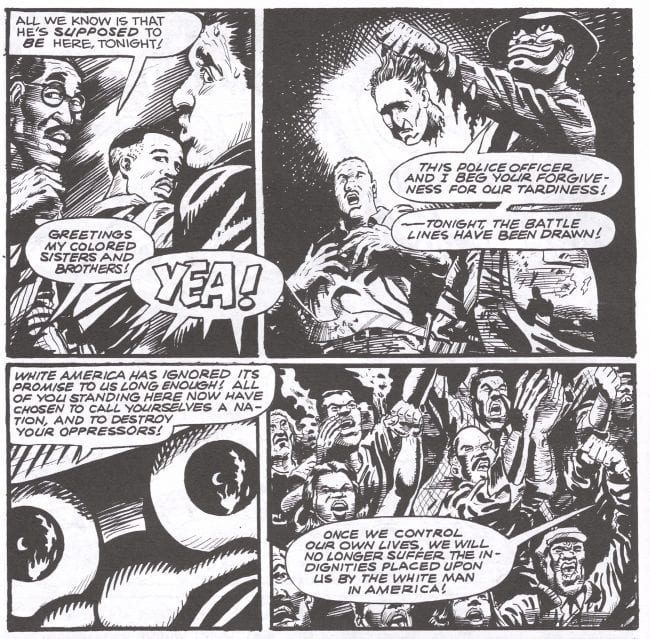

I have dubbed this work a superhero comic, but you could also call it proto-cape pulp hero saga. Early on, we catch a glimpse of a newsstand crammed with comic magazines; it's 1937, the year before Action Comics #1 introduced Superman and all his accordant popular baggage. The Devil narrates, though we never catch a good look at his face; we know he studied as a young man in the Harlem of the 1920s among W. E. B. Du Bois and Timothy Thomas Fortune and Marcus Garvey, and that he mastered "a unique African fighting method" overseas and forged a mighty opposition to colonialism. But the only face we know to associate with the Devil is one he has chosen: a wax Little Black Sambo mask, paired with a working man's suit and an enormous curved machete.

"White people look at what you are, and not who you are," remarks a supporting character, neatly setting out the Devil's contraction: he dresses as all the most denigrating assumptions American society might have about a black man, and then behaves in a manner demonstrably superior and utterly without mercy. He thinks to usurp, and fights to kill. In the parlance of mid-'90s spandex he would be termed an anti-hero, perhaps akin to a horror character, his blade and suit drenched in blood. But, obviously, the iconography active in his design goes far deeper into comics history, all the way back to the most 'traditional' depictions of black people as comedic minstrel figures, an acrid and enduring shorthand. To me, graphically, he seems like Will Eisner's The Spirit and Ebony White combined into one damning person.

And the mystery he is out to solve is especially grand.

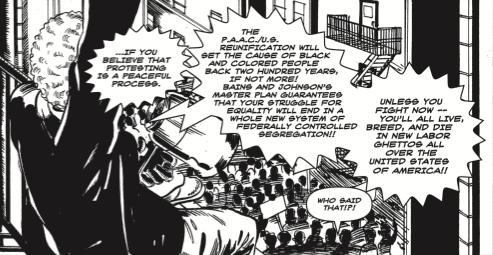

A few digressions aside, Richmond's story mostly ping-pongs back and forth in time between 1937 and 1968; between those years, Jay Bee Dee rouses a full-on popular uprising that results in the formation of the Pan African-American Coalition, an independent nation in the northwest of the United States. Revolutionaries, however, do not always make reliable leaders, so that by '68 a certain Bill Bains -- gangster and dope-dealer fortuitously turned founding father of the P.A.A.C. -- is now brokering a reunification deal with President Johnson, much to the dismay of a still-living Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who is right to be suspicious; Bains is in league with the FBI, which hopes to extinguish the existential threat of black radicalism. Nobody has seen the Devil for decades... and yet, his image lives on among artists, relatives and protestors, to the point where he might be seen as an open-source superhero, sans Guy Fawkes gear or the Time Warner sponsorship.

There are many, many ideas racing around in this comic; far too many for the limited space Richmond & company have at use. We don't learn very much about the functioning or administration of the P.A.A.C., nor are its practical economic and social effects on the U.S. more than allusive. It suffers, sometimes, from the inexperience of its team; Anderson, the first-timer, has some difficulty distinguishing the ages of various characters, which creates a good deal of confusion when inter-generational revelations are introduced into Richmond's scenario, already uneasily burdened with communicating the background of his alternate history while trying to adopt the form of a political thriller. Of course, if we're thinking of the title character as a pulp hero, it's fair to note that a lot of debut stories and books are uneven and misaligned like this, with future volumes adding background and 'world-building' and a sophistication that comes with continued practice.

I don't need to tell any of you that the American comic book market crashed in the mid-'90s. Even in the best times, a creator-owned title from a small publisher faces all the trials of learning on the job in a crowded market. Not to diminish the skills of a Ta-Nehisi Coates, but to work with an establishment force like Marvel is to avail yourself of particular editorial guidance and the slick aesthetics of expert specialist artists; these benefits were not available here, though Richmond has a not-dissimilar fascination with national leadership and political/familial/historical maneuvering. His conclusions are unsparing.

"To some, JBD may be a concept that is past its time in the post-Obama America..." So muses Anderson, neophyte artist turned publisher, in his introduction to the current edition. "But it is exactly because of this America, where the nomination of an African American dispelled the American lie of racism, yet pulled back the underbelly of the still-seething tension lying just below the surface, where people are being convinced to vote against their best interests in the goal of making this great nation a plutocracy, where there are a greedy few actively working to pacify the masses, to stop critical thought and social progress that we need a JBD." He frames this in terms of "outrageous discourse" - that which stimulates thought, creativity and action.

I wonder about the fate of such images on the internet; 2016 is different from even a few years ago. In the 1990s, there was power in a black artist confronting audiences with the racist images so common to the popular culture of earlier times, pushing back against the complacency and ahistoric perspectives of the day; think Spike Lee's millennial Bamboozled. To even state the name of this comic, to ask for it in store, might rightly cause unease among the mass of readers. I don't know if that's true anymore, so deeply layered in irony or confrontation the rhetoric of debate has gotten in online discourse. Sneery white boys shouting the name, memes up and down. Though I like to imagine I have put this column together in good faith, and not behaved as a tourist to racialized sensation, I am not so foolish anymore to assume that my participation does not open the door to misuse. And then you think "should I even?", which is both a good question and also the power the motherfuckers hold over you.

But there is another power residing in this story, in its depiction of a liminal America. To give the Devil his due is to understand that to effect the spirit of justice is to prompt great shifts in social thinking. The Devil as bringing light, and offering the fruits of knowledge. Protest, to him, is destruction, but destruction is only the prelude to reconstruction. He does not mean this in terms of a shift in the Presidency, but in accosting the makeup of the U.S. self-identity to finally ascertain the humanity of persons. All of the heroes in this comic eventually abandon the United States, for new terrain within its old borders. Repressive extremism is normal, which means it can comfortably worsen, and the answer is to push harder, harder still.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday identified in the column title above. Be aware that some of these comics may be published by Fantagraphics Books, the entity which also administers the posting of this column, and that I also run a podcast with an employee of Nobrow Press. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting. You could always just buy nothing.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

Sunny Vol. 6 (of 6): Being the final installment of Taiyō Matsumoto's wistful drama set among children in an orphanage, inspired by the artist's own experiences of living in foster group care. Not yet 50, Matsumoto is a master comics visualist, and it is highly unlikely you will encounter a *lovelier* book this week. A 216-page VIZ hardcover. Note that earlier this year Matsumoto released one of those comics French and Japanese cartoonists make in association with the Louvre, so if tradition holds we should be seeing an English publication of that in due time; $22.99.

A Cosplayers Christmas: Following up on the Perfect Collection edition of Cosplayers from earlier this year -- which isn't a joke or a misnomer or anything, Perfect Collections are often aspirational in anticipating several volumes to come -- Dash Shaw and Fantagraphics bring a new 24-page color comic book stocked with affectionate (and seasonal) comedy set among young adults who enjoy dressing up as popular or niche culture characters. Alternative comic books are like little Christmases that appear on a slightly more frequent basis; $4.99.

--

PLUS!

Days of Darkness: Speaking of b&w indie outlets of the 1990s, Caliber Comics is back in business with a library of new and old works, almost half a dozen of which are in stores this week. There's a revival of the Caliber Presents anthology out there, but I'm going highlight this 184-page compilation of a 1992-93 Apple Comics series (the fruit of Fantagraphics co-founder Michael Catron) from artist Wayne Vansant (of many issues of Marvel's The 'Nam). It's a dramatic look at episodes of struggle from WWII; $19.99.

Twinkle Stars Vol. 1 (&) Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt Vol. 1: Two debut manga picks of very different types. Twinkle Stars is a two-in-one (i.e. 384-page) Yen Press release for a 2007-11 romantic shōjo series from Natsuki Takaya, creator of the megahit fantasy series Fruits Basket. This one is in more of a slice-of-life vein. On the other hand, Gundam Thunderbolt pretty much has to have big robots going to war or else the creators will be jailed, right? Don't make assumptions about the demographic, though - plenty of women enjoy Gundam, this series' serialization in the adult male environs of Big Comic Superior notwithstanding. It's a side-story to the original Mobile Suit Gundam anime, created by Yasuo Ōtagaki of the space program drama Moonlight Mile. VIZ publishes at 248 pages in hardcover; $20.00 (Twinkle), $14.99 (Gundam).

Revolution: G.I. Joe #1: Not actually Japanese here, but traveling in a very manga-informed direction due to artist Giannis Milonogiannis (recently of Image's Prophet), working with colorist Lovern Kindzierski. The writer is Aubrey Sitterson, whose played various roles in the comics industry, though I know him mainly as the fellow who writes the English localized text for the Yo-Kai Watch manga, just to close the circle here on valuable toy-related properties. An IDW release. Preview; $3.99.

Judge Dredd: The Daily Dredds Vol. 2 (&) Mega-City Undercover Vol. 3: A pair of UK import items from Rebellion, home of 2000 AD. The Daily Dredds did not appear in that weekly forum, however, running instead in the Daily Star (here from 1986-89) for readers who needed that extra touch of authoritarianism to get through their day. Written by John Wagner & Alan Grant, with art by Ian Gibson, Mike Collins, Barry Kitson & Steve Dillon, so these had authentic thrill-merchants involved. Mega-City Undercover presents crime stories from the periphery of the Judge Dredd universe, 2011-12, written in turns by Rob Williams and Andy Diggle, with art (respectively) by D’Israeli and Ben Willsher; $38.99 (Daily), $18.99 (Undercover).

Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse Vol. 10: Planet of Faceless Foes (&) The Don Rosa Library Vol. 6: The Universal Solvent: Disney antics via Fantagraphics, from differing points in history. Planet of Faceless Foes is fronted as always by the great Floyd Gottfredson, taking his crew deeper into the midcentury with newspaper strips. The Universal Solvent collects Duck comics from 1995, authored by the most beloved of their latter-day talents; $35.00 (Mickey), $29.99 (Rosa).

Ôoku: The Inner Chambers Vol. 12 (&) Moomin and Family Life: Two completely different releases paired for absolutely no reason other than they are continuing projects which may interest some of you. Ôoku is the continuing Fumi Yoshinaga josei fantasy of a matriarchal feudal Japan, sitting a comfortable one volume behind the Japanese releases. From VIZ. Moomin and Family Life is a 40-page color version of a storyline from Tove Jansson's newspaper strip of gentle satire among soft beasts. From Drawn and Quarterly;

Super Weird Heroes Vol. 1: Outrageous But Real!: This is the new Craig Yoe project from IDW, tackling the probably-fertile ground of oddball Golden Age superhero comics. I do not envy any collection going head to head with the 2009 Greg Sadowski collection Supermen!: The First Wave Of Comic Book Heroes 1936-1941, the absolute gold standard for this sort of thing, but there's probably room enough for another 328 pages. A second volume is already planned for next year; $39.99.

Watchmen Collector's Edition Box Set: Finally, in case you have some need in your life for a version of Watchmen that formats each of its 12 component issues into 7.6" x 11.6" hardcover books which are then put into a box, you may now elect just such a consumer option. Hey, did you know next year is the 50th anniversary of the first appearance of Steve Ditko's The Question? DC should totally celebrate by collecting all of the Charlton Hero Ditkos into accessibly-priced volumes with prudent coloring. I dunno, call it "Before Before Watchmen", whatever you cats want; $125.00.