Roy Crane and Milton Caniff were lured from their first, long-established newspaper comic strips by King Features Syndicate—the MGM of its field. King offered the slickest, most lavish-looking newspaper comics. Slick is a byword for dull, and the syndicate’s worst offense was its tendency towards blandness. Roy Crane’s forthrightness and expressiveness as a comics maker were at odds with the King Features house style. The brasher aspects of Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy—the broad LICKETY WHOPs and tongue-lolling expressions—sat well with that strip’s largely rural readership. His new strip, Buz Sawyer, was aimed at a more sophisticated sector of the American audience. Some of the old Crane blood and thunder remains, but big gestures become smaller, and a less explosive tone, possibly suggested by Crane’s King Features editors, takes its place.

This said, Buz maintained a surprising, sometimes shocking approach to violence and danger for its first decade, by which time Crane stepped away from the bulk of the art duties and let his assistants—whom he often nitpicked—do the heavy lifting. The strip remained reasonably interesting, though it often felt like a PSA for the U.S. Navy and took a more hawkish political tone.

Caniff’s Steve Canyon was more complex, intense, and brainy that usual for this syndicate of light adventure fare (Mandrake the Magician, Radio Patrol, King of the Royal Mounted). Caniff had an out; his strip was officially syndicated by Field Enterprises but distributed by King—a complex situation which allowed the cartoonist to keep the rights to his creation.

Crane and Caniff left their respective strips and syndicates lured by the idea that they could start afresh and create a comic strip with a more mature readership. These two men deeply influenced continuity comics storytelling, from its look and feel to the complexity of a prolonged narrative. (The high volume of Crane and Caniff imitators in the pages of early comic books attests to their wide influence.)

Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates, begun in 1934, became a World War II strip. Steve Canyon was Cold War material from the get-go. Crane’s Wash Tubbs/Captain Easy, apolitical storybook adventure through the 1930s, became a topical war/espionage strip by 1940, before America officially entered the global conflict. The last two years of its daily strip, in Crane’s hands, are a grim march through the bloody fields of warfare—masterful narratives that are hard to revisit due to their bleakness.

Buz Sawyer offered Crane a new beginning and a grueling workload. In later years, Crane groused in later years about having to do a comic strip without assistance. His righthand man on Tubbs, Leslie Turner, stayed with the strip, which he continued through the end of the 1960s. Sawyer’s first full year is more of the same—brutal war narratives occasionally leavened with slapstick humor.

Its main character was no rootless soldier of fortune. John S. Sawyer had a small-town family background in Texas, and was a seemingly well-balanced, ideal red-blooded American boy. A college football hero, he had a wealthy girlfriend back home, Tot Winters, whom he seemed destined to marry. During a home visit in late 1944, Winters’ father takes Sawyer aside and intimates that he’ll have a cushy postwar job in the Winters underwear company.

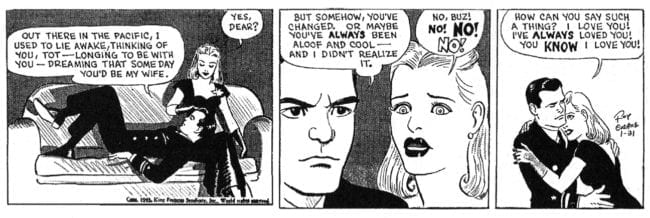

Tot is arrogant and petulant. Her encounters with Buz never feel warm or welcoming. Buz feels obliged to marry Tot but has obvious misgivings about his future. On December 29, 1944, Christy Jameson literally rides into his life—on horseback—and begins one of comics’ few mature, reasonably realistic domestic relationships.

This is the triumph of Buz Sawyer. Though full of violence—with moments of stark brutality that rival Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy—Sawyer is a character study that inverts the romantic notion of the soldier of fortune and shows the impact of an adventurous life on a down-to-earth marriage.

Christy is a breath of fresh air in Sawyer’s life. Outdoorsy, tomboyish, and upbeat, she connects with Buz in a soulful way.

As the war in the Pacific nears its end, Sawyer is torn between Tot and Christy. Marriage of convenience or marriage of love? As well, he is bedeviled by the exotic and obsessive Sultry, an aggressive femme fatale he met during the war.

Fate settles the score on February 5, 1946, when Tot Winters falls to her death from a penthouse balcony—in one of the great (and often reproduced) shocks of comic strip history.

After Buz and his sidekick Rosco Sweeney endure a grueling misadventure in Greenland, the Sawyer/Jameson relationship comes into sharper focus. Sawyer is hired by Frontier Oil to be their globe-trotting trouble-shooter—a post-war revision of the breezy soldier of fortune. He’s tethered to a corporation and subject to the irritable whims of his stern boss, Mr. Wright, frequently seen in a scowling profile, a cigar parked in his lips as he barks life-changing orders to this heroic man-child.

Buz’s next assignment, after the Greenland job, is to find Wild Bill Daniels, a pilot who seems to have disappeared in the wilds of “Salvaduras,” one of many faux Latin-American settings Crane used in his career. Sawyer’s main interest in the case is that Christy Jameson and her father are there. Roy Crane the romantic emerges in this sequence, which expands to the color Sunday strip—otherwise a nuisance demanded by the syndicate and barely touched by Crane for most of its run.

Here, Buz and Christy finally connect, and the patterns that mark their relationship emerge. Christy wants to engage with Buz in his colorful life as an international problem-solver—work that often has brutal outcomes. When Christy does participate, fate deals her harsh blows. She would prefer that Buz take a quiet desk job and be near her. She also realizes that the conditions of this relationship insist that Buz be free to travel the world and place himself in constant danger.

In Salvaduras, Buz—and Crane—open up their hearts. The September 7, 1946 episode is a visual essay on the birth of a loving relationship:

On October 4, 1946, Buz confesses his love for Christy. Crane makes it a big deal and spends several days celebrating this union with symbolic drawings and terse epigrammatic prose.

He’s done this routine many times in his two decades-and-change of newspaper strips. Every time Wash Tubbs, the protagonist of his prior feature, falls in love, there’s a similar ado of hearts and flowers. The relationship of Buz and Christy is no breezy affair. It has growing pains, ups and downs, and often seems more of an ideal than an achievable reality.

Crane gave himself and his strip a maturity that few other syndicated cartoonists cared to encourage. It took Chester Gould almost 20 years to wed Dick Tracy and Tess Trueheart (their union trails Buz and Christy’s by one year). Tess is less involved in her husband’s work life, and only occasionally suffers from their union; in 1994, Tess served her husband with divorce papers, claiming she was sick of his spousal neglect. They patched things up.

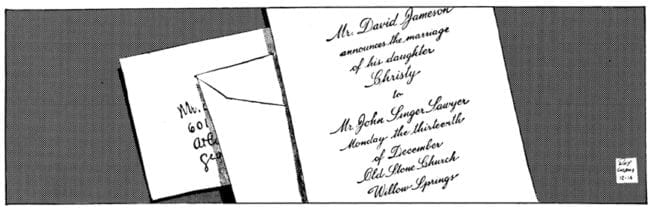

The two years between Buz’s confession of love and the December 13, 1948 wedding are full of danger, discomfort and uncertainty. They also suffer from intervals with zero Crane art involvement, as his need for travel and research caused the strip to be drawn by syndicate hacks for six to eight-week stretches.

Buz and Christy have a winter wedding (on 12/13/48) and Crane stops his story for an elegant and reserved announcement:

He sends the newlyweds on a tropical honeymoon—a moment of calm and communion in a marriage that will seldom experience such bliss. Crane gives the newlyweds privacy for the closing weeks of 1948 and into the new year, as Sawyer’s sidekick Rosco Sweeney has a grueling outdoor adventure as the Sawyers take a vacation from their own strip.

Crane’s spent a year of his late 1940s Buz Sawyer to explore the married relationship of Christy and Buz. Perhaps the most unusual and gripping stretch of all Buz Sawyer takes place from January to June of 1949. It’s as close as syndicated comic strips got to the vision of British filmmakers Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. The flavor of their stunningly designed films, which treats unusual subject matter with heated theatrics (as in Black Narcissus [1947] and Down to Earth [1950]), meshes well with Crane’s post-war approach to comics storytelling. As one reads this sequence, it’s not hard to imagine the live-action Technicolor film that might have been made of the same material.

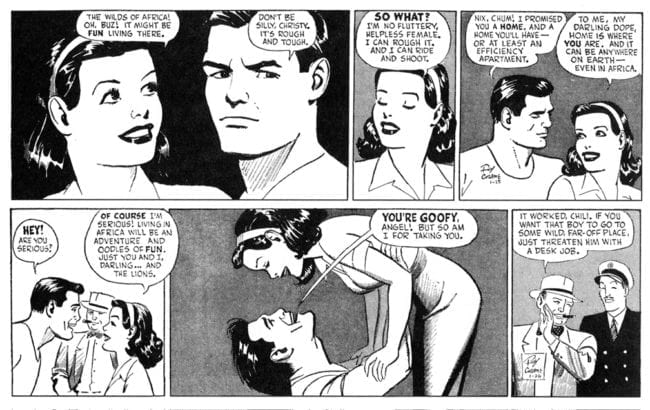

It begins as Frontier Oil offers Buz a desk job at their New York headquarters. “You’ll want to settle down where you can enjoy a normal home life,” Mr. Wright commands him. The next day, Wright mentions a tough assignment in Africa, where Frontier has purchased oil land.

Buz lights up at the prospect, but opts for the city job, as he thinks it will please his new wife. She challenges her husband—and herself—to go for the Africa job—exactly as the cynical, manipulative Wright hoped it would happen.

The transition from America to Africa is depicted as plodding, frustrating and difficult. Crane compresses four weeks of ocean voyage into one panel of a daily strip. His captions, worded like frugal telegrams, paint a blunt picture of the rigors of their journey:

The Sawyers abide the trek with a mixture of love and sarcasm. They address one another as chum, darling, pal, sweetheart and genius. They complement each other. Christy thinks of things that elude Buz, and vice versa. Theirs is a jaunty democracy. They work well together under stressful conditions. The long safari they take to get from their port of entry to Frontier’s property is grueling. Some days, the trek advances only 100 feet. At night, their camp is ravaged one night by a bored rhinoceros.

Once they reach the site, they’re initially pleased. The land is abundant with fish and fruit. A master of the graphic landscape, Crane creates dense duo-tone images that bring the reader deep into the exotic and forbidding locale.

After a lion attacks their camp and kills one of the porters, some of the romance evaporates for Christy. She is resilient and insists that Buz have their pre-fab home built so they can have the relative security of a roof overhead.

Christy finds the house drab and barren and improvises hand-made furniture and native décor elements. Buz is impressed.

The newlyweds acclimate to the routine of frontier life. Christy tends a garden that she must defend from snacking baboons and elephants; Buz buys cows so they can have fresh milk and butter. His work demands that he leave Christy alone in the wilderness during daylight hours. And thus, their marriage receives its first great test. Their presence is noted by Kingston Diamond, an unctuous ex-pat who dresses like a tropical dandy and fixates on Christy.

Christy is surprised by his presence and guarded at first. They bond over glasses of fresh buttermilk (which must have been a favorite of Crane’s; he rhapsodizes about the stuff often in Buz Sawyer). Buz returns home and gives Diamond the stink-eye. “How did THAT oily, over-dressed drip happen to trickle in?” he asks Christy. She finds Diamond charming; he smells a rat.

Diamond withholds his feelings for Christy and pays light social attention to her until a moment of crisis. Out hunting game for dinner, Christy is chased by a rhino and then treed by a water buffalo. Diamond senses an opportunity and rescues her.

By this time, it’s dark, and Buz drives off to search for his wife. He has an accident with his jeep and soon finds himself surrounded by lions. Buz is mauled by one of the cats and is bleeding to death when Christy and Diamond spot him up a tree.

In Crane’s comics, things take a turn for the worst kind of worst. Just when you think some event in a story couldn’t get more fouled up or threatening, he makes it surpass your expectations. By the late 1940s, Crane’s eye had a mastery of restraint. The blundering, ballooning shapes of chaos leave his work. This underplays the violence or threat he portrays—and probably helped get these moments intact on America’s comics pages.

As Buz recovers from his injuries, Diamond moves in on Christy. He catches her bathing in a pond and confesses his love for her. She does not share his feelings. Delirious with jealousy and pain, Sawyer banishes Diamond from his home. The ex-pat cad doesn’t give up easily, and after Buz is functional enough to leave the house, Diamond attacks him and leaves him for dead.

He knocks on Christy’s door, which is barred and blockaded, and informs her of her husband’s apparent death. After he bashes in the door, Christy kills him with a spear.

I’m leaving out some plot details that might sound ludicrous if described. The moment of Diamond’s demise is jarring—it’s the last thing you expect to happen in a King Features strip. If this were Dick Tracy or Little Orphan Annie, such mayhem wouldn’t seem as shocking. In the genial duotone world of Roy Crane, it’s walloping.

The Sawyer marriage survives this drama and trauma. Christy surrenders herself to the authorities, who excuse her act as being in self-defense. The rattled young marrieds, their job finished in Africa, head back home to pick up the pieces. On the way home, a chimpanzee Christy has adopted causes screwball mayhem on an ocean liner. This light-hearted froth—which always seems a bit forced in Crane’s hands—attempts to ease the reader away from the dark love triangle they’ve spent the prior six months taking in, three panels at a time.

Crane has been criticized for his racism, which informs this sequence in subtle ways. Diamond plays on the native people's lore to disguise a series of murders he commits, towards the end of the narrative. We are not confronted with any overt statement that these Africans are naïve and simple-minded, and thus prone to fall for Diamond’s crude plans. It’s quietly embedded in the sequence.

Finding joy in reading Crane is challenged by the google-eyed porters and lip-licking waiters who appear as background decoration in his work throughout the mid-1940s, and seldom play a substantive role. Crane didn’t go as far as, say, Chester Gould, whose simpering, sweaty, and craven Memphis Smith became a major secondary character in Dick Tracy in 1936 and '37.

Crane had cut out this casual racial caricature, at the request of King Features’ editors, by the end of the 1940s. The African characters in this six-month sequence, are drawn starkly—almost in an Expressionist style—with a tendency for broad strokes. But the characters serve a valid and positive narrative function. They are not the villains of the piece. That dubious honor goes to Kingston Diamond—a sort of David Niven gone to seed and unable to control his base impulses. If Crane cared to make a point here, it is not complimentary to his fellow Whites.

The Sawyer marriage suffers a closer-to-home crisis from January to June 1950, in a sprawling storyline that begins with another idyllic vacation gone awry. Relaxing after a seriocomic fiasco in an unspecified “Central American republic,” a rash impulse of Buz turns the couple’s life into a noir-ish nightmare.

By this time, Crane’s role in the strip was in the process of shifting from hands-on auteur to overseer of a creative team. Though he continued to do a fair deal of the artwork, and much of the plotting, he relied on author Edwin Granberry and artist Hank Schlensker. In this 1950 narrative, Schlensker’s cartooning style often pops out in elements of panels, in an effect akin the artists who inked Jack Cole’s Plastic Man stories of the later 1940s.

Crane had a difficult relationship with Schlensker, who had drawn the wartime adventure strip Biff Baker for NEA before joining Crane in 1946. He became an able-bodied impersonator of the Crane style as more of the strip’s visuals were entrusted to him in the 1950s. (The Sunday strip, which was mostly unrelated to the daily, was ghosted for most of its run by Clark Haas, Al Wenzel and other cartoonists. Crane would jump in for a few weeks, here and there, if he had an idea for a Sunday continuity, but it was a nuisance to him and he was glad to have others take care of it.)

This 1950 narrative avoids the picaresque adventure themes that were Crane’s métier. It’s fascinating to see him try to sidestep the intrusion of blood and thunder into an involving narrative of everyday life.

The story begins when Buz and Christy lounge on the beach outside their coastal cabin. She has a roast in the oven; there is no call to adventure, or the other typical interruptions that would shatter such a lull. They decide to go fishing and rent a rowboat. An immature and irresponsible action on Buz’s part takes them miles from their cabin and leaves them stranded, near-naked, on a sandbar. The even-tempered Christy lets her man-child spouse have it:

This doesn’t change their situation. After shivering at night and broiling under the direct sun, Buz opts to swim back to their cabin. He finds the oven smoking with the remains of the blackened meat and returns to the sandbar with his sea-plane. Only Christy isn’t there. He finds a trio of coastal ne’er-do-wells who feign no knowledge of Christy’s presence.

Buz combs the mangrove-clustered shoreline and nearby houses. He turns up Christy’s polka-dotted bathing suit—which he IDs by a repair done to it—but no trace of his wife. He tangles with the fellows he found on the sandbar and escapes in a stolen boat.

Meanwhile, Christy, dazed and barefooted, clothed in a plain dress, is found walking down a rural roadway. She can’t recall who she is, or where she is. She remembers the roast in the oven—a nice touch that lends verisimilitude to a potentially loopy story.

Buz encounters his old nemesis Harry Sparrow, in an interlude which serves no purpose in this amnesia story. Christy wanders into the hiding place of a pair of bank robbers—one who resembles Kingston Diamond, who was a Crane “type” like the Wallace Beery-esque lugs and wide-eyed flappers that peopled his comics from the Jazz Age to the Atomic Age. Her obsession with checking their oven for the burning roast spooks the crooks, who flee and are soon caught. Christy trudges on and is alone in the rain in an anonymous city. Here, Crane has an atypical moment of urban noir, with his teletyped captions lending a rough air of poetry:

Buz finds traces of Christy’s presence, but keeps just missing her. She becomes part of a sleazy carnival, where she’s billed as a “Princess Sheeba from Arabia”—a scantily-clad dancing girl. Though the carnies befriend her, Christy isn’t comfortable with this life, and once again barely misses contact with her husband somewhere in Tennessee.

Fate lands her in her hometown, where she attempts to get into her childhood home, which has long since been occupied by new residents. She chances upon the home of Buz’s parents and drops in to visit. She speaks of Buz as if she hasn’t seen him in years. Buz’s doctor dad examines her and determines that she’s amnesiac. By this time, Sawyer has tracked her down. He is crestfallen—not because it was his rash actions that started this chain of events.

On her own, Christy finds the wedding announcement—the one Crane ran in mid-December 1948. That makes it clear to her that she and Buz are married. Some artifacts from their 1949 African trauma-fest jar her memory back:

Notice that Kingston Diamond is not among the shadowy figures that flood Christy’s head. In a narrative that has used several call-backs in the service of a story about memory, Diamond’s absence is a surprising omission.

She confronts Buz about his responsibility for all this fuss and bother. He affects a gee-whiz, boyish “Honest, angel. I had no idea [I’d] cause so much trouble.” Christy lightly upbraids her husband, but Buz remains off the hook for putting his wife through half a year of existential hell.

These two half-year narratives are driven by the element of marriage. Christy is strong-willed for a female pop-culture character in mid-20th century America. Her subservience to her husband takes precedent over her right to be a strong individual. She is a likable and interesting character—more so than Buz—and it’s painful to see her suffer as she attempts to assert herself in their marriage. That she asserts herself at all—and voices her negative opinions of Buz, though couched in mock-anger and sarcasm—is progressive for the late 1940s.

Nagging housewives filled America’s humorous comic strips—from Maggie hurling crockery at Jiggs to Major Hoople’s wife deflating his ego at every turn. This abusive relationship template continued late into the 20th century via strips like Bill Hoest’s venomous panel cartoon The Lockhorns (which continues on long after Hoest’s death, offering a suburban version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? minus the intellectual parts).

To see a comics creator of the 1940s attempting to depict marriage, within the genre confines of an adventure strip, as a harmonious (if hazardous) life is fascinating. If it seems naïve and sexist to us now, it was new ground for comics, broken quietly in an unlikely corner of the funny page.