Come On Pilgrim

The Doom Patrol have always been an outlier in DC’s firmament of spandex stars. Whether or not, as co-creator Arnold Drake (alongside Bob Haney and Bruno Premiani) was wont to speculate, Stan Lee stole the basic shape of the premise for Marvel’s X-Men, the feature nevertheless tasted slightly different than the rest of the line. They were superheroes, yes, but explicitly positioned as outsiders and freaks. Their powers were more curses than gifts, leaving them stuck on the outskirts of a society that would only ever tolerate their scruffy presence alongside the lantern-jawed likes of Superman and Green Lantern.

(As for whether Stan actually stole the idea of a group of misfit superheroes on the outskirts of society who fought to protect a world that hated and feared them at the command of a wheelchair-bound genius, we may never know at this late date. But honestly I would tend to think not, since while Stan was a thief, he was a lazy thief who preferred to grab whatever was close at hand. I could be persuaded, certainly, but the burden of proof would rest on whoever could prove that Stan ever paid close enough attention to National to ape a brand-new mid-tier launch mere months after release.)

The first run of the Patrol lasted thirty-five issues before cancelation in 1968. Low sales led the team to be unceremoniously murdered on-page, leaving the creators to urge readers to write in to save them. That didn’t happen, and the concept languished for nine years.

The man responsible more than any other for the Doom Patrol’s survival in the subsequent decade was Paul Kupperberg. He loved the team and introduced a new version in 1977, in the pages of the company’s deathless Showcase anthology. It wasn’t that memorable, truth be told, and even Kupperberg admitted that the relaunch flubbed the concept by turning them into something more along the lines of cookie-cutter superheroes. But even if that relaunch failed to clear the pad, the concept wasn’t completely dead. With Beast Boy’s inclusion in the 1980 New Teen Titans relaunch, the team and concept were kept from fading completely. The first story of the Titans’ second year saw that team finally investigating the Patrol’s original murder, as well as the return of their arch-foes the Brotherhood of Evil. They stuck around, in a modified membership, to bedevil the Titans for a while.

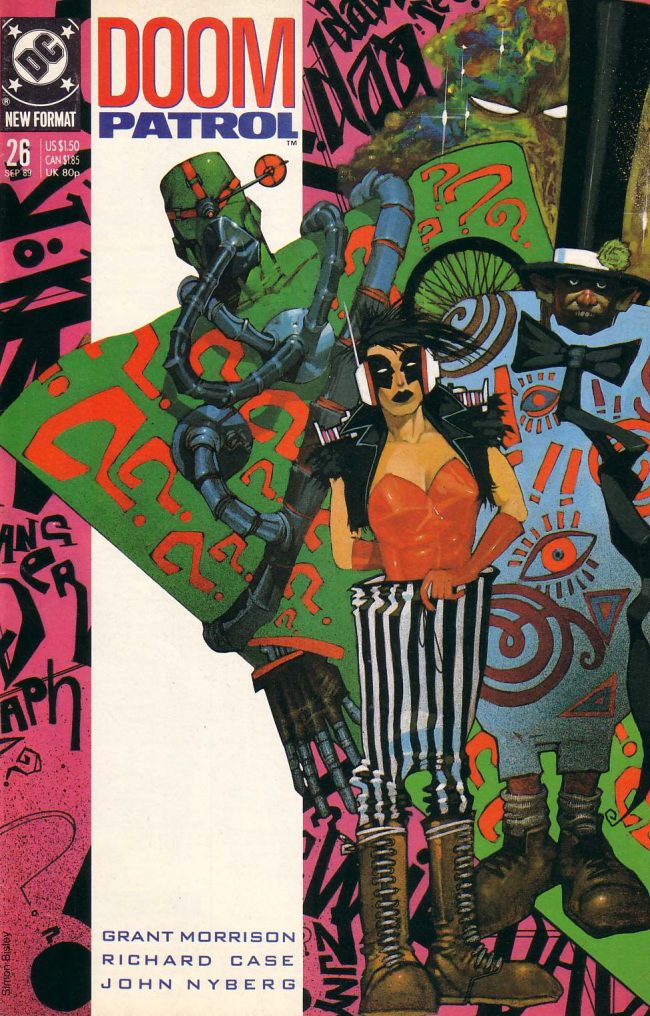

Kupperberg kept at it, and in 1987 sat at the helm of an actual revival. It’s easy to overlook in light of everything that followed, but the relaunch didn’t start out badly. It had interior work from Steve Lightle, which was - for 1987 - kind of a big deal. He didn’t stick around very long. Apparently he had been promised plot input, on which Kupperberg didn’t follow through. Lightle’s successor, a very young Erik Larsen, sidestepped this by simply not drawing the parts of the script he didn’t like. The editor apparently didn’t mind.

Kupperberg kept at it, and in 1987 sat at the helm of an actual revival. It’s easy to overlook in light of everything that followed, but the relaunch didn’t start out badly. It had interior work from Steve Lightle, which was - for 1987 - kind of a big deal. He didn’t stick around very long. Apparently he had been promised plot input, on which Kupperberg didn’t follow through. Lightle’s successor, a very young Erik Larsen, sidestepped this by simply not drawing the parts of the script he didn’t like. The editor apparently didn’t mind.

If this potted history convinces you of anything, it should be that up until 1989 very few people really gave a shit about the Doom Patrol. Kupperberg’s second shot was, if we’re being completely fair, significantly better than his first. The stories were a bit weirder, the characters more troubled, but Lightle’s abrupt exit and Larsen’s relative inexperience and more traditionalist leanings kept the series at a fairly low boil. The new Doom Patrol was unlikely to reach the end of its second year unless something radical changed, fast.

Now is where the story of the Doom Patrol’s renaissance usually begins. Grant Morrison had already built a name for himself on this side of the Atlantic after having relaunched Animal Man in the wake of Crisis on Infinite Earths. The typical narrative also mentions that Morrison was then one of a handful of young up-and-coming British writers who had been poached by the company to breath life into their moribund mid-tier. The influx of foreign talent that followed swiftly on the heels of Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing is still commonly referred to as the “British Invasion,” even if every one of the writers so implicated publicly chafes against the label. Moore in particular doesn’t appreciate the blame.

But there’s another story here, or at least, the shadow of one: Erik Larsen only worked on the series for a little under a year - issues #6-15 - and honestly the best thing about the run is the covers. But even just a glance at those covers betrays that even if Larsen was still very young, all the main ingredients of his work were there from the beginning. Part Kirby, part Miller, and part manga, Larsen’s work may have been an ill-fit for a team of supposed moody misfits, but it already had every bit of the energy and dynamism that he would soon become famous for at Marvel. It already had all the shortcomings as well, for what its worth, to which any glance at the rapidly expanding cup sizes of his heroines can readily attest.

But there’s another story here, or at least, the shadow of one: Erik Larsen only worked on the series for a little under a year - issues #6-15 - and honestly the best thing about the run is the covers. But even just a glance at those covers betrays that even if Larsen was still very young, all the main ingredients of his work were there from the beginning. Part Kirby, part Miller, and part manga, Larsen’s work may have been an ill-fit for a team of supposed moody misfits, but it already had every bit of the energy and dynamism that he would soon become famous for at Marvel. It already had all the shortcomings as well, for what its worth, to which any glance at the rapidly expanding cup sizes of his heroines can readily attest.

Still: there was a period in the late 80s when not just Erik Larsen but Todd McFarlane and Rob Liefeld were producing steady work for DC on a number of prominent titles. McFarlane pencilled the first half of the Invasion! crossover, which still remains one of my favorite things he’s done simply because its such an uncharacteristic fit - over a hundred pages of the wonkiest DC outer-space bullshit, in a crossover specifically designed to draw connections between the company’s present day line and the Legion Of Super-Heroes, 1000 years in the future. He also did a few issues of Detective Comics - the ill-starred Year Two - as well as two years of Infinity, Inc. Liefeld was responsible for the art for a revamped Hawk & Dove miniseries, helping to reintroduce Steve Ditko’s strange war & peace duo for the modern era.

It is remarkable, at thirty years remove, just how close DC came to realizing the value of what they had in the moment. But the company’s editorial culture just wasn’t designed to accommodate the kind of radical departure from the status quo that the Image founders represented. In terms of art, DC was stuck in the mode of being permanent farm team to Marvel’s big leagues. More damning still, the company seemed to embrace the position. DC’s stable was stocked with reliable pros who valued a steady paycheck and young up-and-comers, both categories of folks who could be counted on to turn in reliably consistent work without upsetting the traditional top-down management style preferred by the company since time immemorial. Only about half of that was true, which is why the kids had a habit of getting better jobs at Marvel the moment they started to pitch any heat.

With that in mind it maybe doesn’t seem quite so remarkable that it was a group of young British writers and not young American artists who captured the company’s spirit at the time. The relentless focus on attitude and style over substance that characterized the Image founders’ early Marvel work would have probably gotten them fired at DC, whereas Marvel was smart to recognize that the younger artists understood precisely what their audience actually wanted. For better or for worse.

Letting those young British writers sidestep the Comics Code entirely was a telling concession. The Code hasn’t appeared on Marvel book in almost twenty years, but for decades previous DC was the only one of the Big Two that regularly sold books without the seal or even the expectation of the seal. (Subsidiary lines like Epic notwithstanding.) It limited sales for certain titles to the Direct Market at a time when lots of comics were still sold in big bundles to newsstands and grocery stores. But the company recognized the benefit, in terms of critical notice, creator goodwill, and a just plain diverse lineup of the kind of books that Marvel was still, to be fair, decades away from publishing. And then only really because they started hiring precisely the same famous writers who DC had picked up for a song years earlier.

Which brings us back to Grant Morrison, fresh at the helm of Doom Patrol following the book’s rather sleepy first year and a half. The team itself had been fed into a meat grinder in the pages of the aforementioned Invasion! crossover. Half the characters were killed outright or otherwise incapacitated, although a couple of the abandoned later recurred as he found uses for them. The first storyline is famously called “Crawling from the Wreckage,” and especially in light of much of Morrison’s later career it’s hard not to detect the sideways glance in the direction of past creators, AKA the proverbial wreckage.

The context of the series’ earlier vicissitudes is important here precisely because it is so rarely discussed. Look at Sandman: how often do you think, in 2019, people get into that series on account of it spinning out of the events of Infinity, Inc.? It did. It literally crossed over with The Last Days of the Justice Society - that’s the Roy & Dann Thomas joint that put the Justice Society in limbo fighting Ragnarok until the end of time. And then they stayed out of circulation for a few years, except for Thomas’ work in the post-Crisis Secret Origins relaunch, as well as the post-Crisis Infinity Inc. - those same comics a young Todd McFarlane drew.

Think about it this way: “The Kindly Ones” is literally just the last part of a story that begun in a Roy Thomas comic book. Some of you got that immediately. That Sandman was a spin-off from the gosh dang Justice Society is completely true and nevertheless not really most peoples’ point of entry.

(And while I have you here: how odd is it that the Justice Society actually had a decent-to-good couple decades immediately after Crisis? I read DC in the 90s, people were incensed whenever they tried to put Alan Scott or Jay Garrick on ice. People liked those guys. Hawkman didn’t bother anyone whenever he was hanging out in the Justice Society - and it’s worth pointing out, the problem with Hawkman after Crisis begin with the sidelining of the Thanagarian version entirely, who just straight-up does not appear anymore in comic books. [How weird is that? Barry Allen gets a call-back, but Kator Hol is ether.] Crisis gets a lot of guff for effectively vitiating the Legion of Superheroes but not a lot for successfully laying the seeds for the freakin’ Justice Society of America to have a turn as DC’s number-two group, even supplanting the Titans for a time. Which was clearly not their intention, to judge from the fact that editorial kept trying to get rid of the characters throughout the late 80s and 90s. That just made people like them more.)

It’s all about perspective. Examine for a moment this proposition: Doom Patrol in the 80s got good once they got rid of the guy who went on to pencil Spider-Man for a few years and cofound his own comic book company. That maybe misses the point completely, but is also more or less true.

Surfer Rosa

So dig this perspective for a second: 1989 was thirty years ago. Thirty years! Quite obvious. But, here’s the thing: I was buying comic books in 1989. I wasn’t buying a lot of DC, but I was sure buying a lot of Marvel - 1989 was a big year for Marvel, in the flush of Tom DeFalco’s early reign. And 1989 is farther away from 2019 than 1989 was from 1961. You know, the first issue of Fantastic Four.

Why, then, did I struggle so long against the growing realization, as I reread Morrison’s run for the first time in a good few years, that maybe - well, maybe thirty years was a long time ago? And long enough that something which once may have seemed absolutely au courant might, in the fulness of time, also appear slightly dated in some respects?

Not dated, perhaps, in a bad way - most extraordinarily important works of art are also irrevocably dated in significant ways. It’s only an insult if you choose to take it that way: it’s simply a statement of fact to say that some aspects of it reflect the times of its composition in ways that were probably more or less incidental to that original composition. You don’t love or hate things more or less because they’re dated, but if they’re thoughtless or mean-spirited or just boring. Dated doesn’t have to mean bad, just different in hindsight.

Why does that seem like a potentially tendentious assertion? I point out again, for comparison, Doom Patrol #19 dropped in the opening weeks of the George H. W. Bush administration, which was as long ago now as JFK had been to me then. It was not difficult to see how dated Marvel comics from the 1960s seemed, in that moment, but it somehow came as a shock when it occurred to me to hold the later books up to a similar standard. Even the most brilliant runs look different in hindsight, and it doesn’t necessarily have to mean bad things. Maybe all it entails is an acknowledgement that some of the beats in the composition don’t land quite the same way now.

Another point of perspective: for all the noise over the many long years of the strange implicit career conflict between Morrison and Moore, they actually share many important things. For both men their early material is touched by the mood of the Thatcher years (albeit filtered through American cultural institutions). Moore started earlier but Morrison was on hand to cover the inauguration of The Nineties and the strange advent of the End of History. I mean, “The End of History” even sounds like a problem the Doom Patrol might have to punch in multiple incarnations.

Now, I should probably mention - I’ve struggled with Doom Patrol for a while. It’s never been my favorite Morrison, even my favorite early Morrison. That honor goes to Animal Man. Perhaps because it resonates on themes very close to my own heart and interests, I’ve always thought highly of it. It’s a very warm-hearted book, even down to the storybook deus ex machina ending. I also think Mark Gruenwald must have really liked Animal Man, although I don’t know if he ever mentioned one way of another - there’s a lot in Quasar that seems in hindsight very much an attempt to answer the tone of Morrison’s Animal Man.

Buddy Baker’s story always resonated with me partly because it seemed to really, really love and appreciate continuity. It was one of the first stories explicitly about Crisis to be written by someone who wasn’t actually involved in any way in the creation of Crisis, or implicated in any way in the decisions therein. It was a story that could only have been written by a fan who recognized that a great deal had been lost, while the nature of the change appeared almost as divine fiat in the lives of people affected, fan and character alike.

Doom Patrol is about none of those things. It’s not particularly invested in continuing anything preceding it. The characters are changed over the course of the run, some rendered barely recognizable. There’s no attempt to play with any of the Doom Patrol’s great rogue’s gallery - Monsieur Mallah and the Brain show up, but I have a few words to say about them below. The Doom Patrol’s great nemesis General Immortus is unseen, save in brief flashback, and the Animal-Vegetable-Mineral Man goes sadly unloved. Garguax probably wasn’t a big loss, truth be told - and, oddly, had been strangely overused during the Kupperberg run - but the Brotherhood of Evil was turned into something else entirely. Which, you know, wasn’t bad, but also wasn’t really the same thing. And, for what it’s worth - most members of The Brotherhood Of Dada were ciphers, at best pasted together out of Creation records fanfic, and at worse an excuse for Morrison to write bad AAVE.

Now, on the face of it, at this remove, it might seem like a churlish complaint: Morrison didn’t use the classic rogues gallery, didn’t do anything to mine the team’s “iconic” past. As is well known, he created a whole bunch of new stuff and new characters, who were more or less left untouched when he moved on. Even when Danny the Street and Jane showed up for cameos in various Doom Patrol relaunches later in the 00s, they were still held back from really taking an active role in the ongoing life of the series. Robotman gets passed on, but that’s the one constant everyone understands. As long as you get the robot right, you can do a whole lot to what’s around him.

The only possible context in which it makes sense to wonder why Morrison left so much of the group’s actual rogue’s gallery untouched is when looking at Morrison’s career as a whole. It only seems unusual in the context of a man who subsequently built a mid-career-renaissance on being able to dive deeper into the old continuity than anyone else. No one else would ever dare to resurrect the Batman of Zur-En-Arrh! That shit had people losing their minds back during W’s second term.

Doom Patrol isn’t a deep dive into old continuity, and sits at an abstruse angle not just generally to the larger idea of continuity but to the Doom Patrol’s own intra-series continuity. It rubbed a lot of people the wrong way, I think, because in some ways it certainly was an aggressive break from the norm. John Byrne drew the Secret Origins annual that preceded the start of the Kupperberg series, as well as the late-00s relaunch specifically designed to wish Grant Morrison’s run out to the corn field. He had a very specific view of what the characters should look and sound like, and it was pretty firmly indexed to 1964. He even got back together with Chris Claremont to relaunch the book, in the pages of JLA (a series launched by and defined by none other than Morrison himself, remember). And that’s quite remarkable, as a thing that they actually published, if not a thing that a lot of people then or now wanted them to publish.

Remember Crucifer? Remember how that very specifically had people not losing their minds back during W’s first term?

But the funny part is, for all the shit that Grant Morrison might have received in some quarters for playing with the hallowed premise of the gosh dang Doom Patrol (a comic so beloved by fandom at the time that almost twenty years had elapsed between ongoing series), the fact is that they did the exact thing with Professor X as the Chief over the next few decades. Not even counting bullshit like Onslaught (and Onslaught? BULLSHIT), Professor X was a jerk who routinely erased peoples’ minds and basically was a terrible kind of moral example to a young and impressionable Scott Summers. Eventually the character was murdered and people didn’t get too worked up because he had been extraneous to the central movement of the series’ plot for a long time. He maybe hadn’t turned as explicitly villainous as The Chief by the end of Morrison’s run, but he’d still been implicit in quite a lot of shit. Rendered kind of not the same guy by the process.

So I guess I’m talking around the problem, said problem being - these comics don’t sit as easily as they might once have, for a number of reasons. They don’t seem so radical, for one thing, now that all their best moves have been copied by subsequent generations. It seems like these book have a lot of something that was very, very cool in 1990 and thereabouts, but which really isn’t quite the same thing precisely as “cool” in 2019. And it’s not like it’s uncool exactly, but nether is it the rather deathless 1960s Batman show, the virtues of which seem more and more enduring with every passing year, as we see that camp silliness was never really something anyone hated but self-righteous nerds. Stuff that purposefully eschews any attempt to be cool often ages better -

- and wow, there’s an insight for ya, hand-crafted and delivered straight to your table.

There’s nothing wrong with “cool,” as such - everyone likes being cool, everyone understands cool. It’s a legible phenomenon. But it’s also fleeting and rarely - rarely - the kind of thing that doesn’t age. It does happen. Hulking leather jackets with big metal shoulder pads is certainly a look . . . but how much hanging around in your closet from that era would you still wear out?

I mean, besides the stuff that came back because all fashion is cyclical. You know, torn jeans, flannels, and Doc Martins with dresses. It’s a trip whenever the clothes people wore when I was a kid come back into vogue. Maybe some people like it. Just makes me feel like I never left high school.

I mean, besides the stuff that came back because all fashion is cyclical. You know, torn jeans, flannels, and Doc Martins with dresses. It’s a trip whenever the clothes people wore when I was a kid come back into vogue. Maybe some people like it. Just makes me feel like I never left high school.

Grant Morrison was different after finishing Doom Patrol, I think, to a degree I hadn’t really appreciated. And the reason I didn’t appreciate is probably that I have never really connected with The Invisibles in any way, shape, or form. I think Invisibles is transmitting on the same frequency as Doom Patrol, which became as much a vehicle for Morrison’s creative id as any other book of the period for any creator. He took that book apart from stem to stern, left it more or less completely inert, in such a fashion that a lot of good men and women spent a lot of good tears trying to get people to respond to any incarnation but. And then the one rebooted version people seemed to go for was the one launched by the recovering rock star that finally promised a semi-nostalgic revisitation of Morrison’s old thema and character group.

Which, I mean. Yeah. Sure. It makes complete sense, especially when you realize, oh yeah, three decades. That makes perfect sense. It’s long enough ago that all the rather precious but also rather important (both things can be true!) possessiveness Gaiman and Morrison in particular were allowed to extend over their particular versions of what are still essentially shared universe characters has faded in favor of a more permissive realm wherein the absent founders’ versions are forever ascendant. Because there’s just more money to be made from the versions of these characters people really like, don’t you know?

DC went out of their way to make things right with a small group of creators who came over in the wake of the guy who started the whole thing having left the party first, feeling significantly fucked over by the experience. It’s been long enough since the end of Sandman that we can say, in fact, Gaiman did return to the character a handful of times in subsequent years. And in exchange for the parent company actually respecting his wishes regarding the series’ primary cast and mythology, the stories he did sporadically in the intervening years weren’t that bad, and I think they fit pretty snugly next to the parent series. The last one, with J. H. Williams III, really was pretty great. I’ll ride for it.

Grant Morrison never went back to more Doom Patrol, but he did one better: after a few years spent spending Joe Quesada’s money out of, I don’t know, boredom, he came back and actually put down roots, became one of The Guys who stuck around and had a bit of, you know, responsibility. Gets to do basically whatever he wants, in perpetuity. And some of its good and a little bit of it has been great and some of it was actually just kind of boring, but there’s always been something new.

Doolittle

Did I lose all credibility with you when I said I never cared for Invisibles? I understand and respect it as a series to which a lot of people really, really respond. I can say, I did finish it, after multiple tries over the years. I never wanted to dislike it. I just found myself feeling kind of genially baffled through most of the run. It was clearly deeply felt, but maybe I just waited too long to read it. I didn’t get through it until I was in my thirties and had already bonded quite sufficiently with the other Morrison, the guy who took a few years off in the early 90s and then followed up Animal Man with JLA. The one where he got to play with All Of The Toys. It wasn’t a perfect run and it honestly ran out of steam for me about two-thirds through, but JLA was the most exciting comic on the shelves for every month he wrote it. That’s saying something, considering it also overlapped significantly with Kurt Busiek’s Avengers, which - while it wasn’t exciting in quite the same conscious and highly structured fashion as Morrison’s five-year experiment in applied superhero brutalism - was exciting every month to me, and isn’t that what’s really important here?

I liked the guy who wrote that. Buy me a Coke some afternoon and I’ll talk about how much I love DC One Million - one of the very best stories the company has ever published. Someone who actually cared about the matter sat down and thought about how best to make the most exciting crossover possible - and I’m not trying to dog on Millennium. I have read Millennium. It wasn’t that great, but did the job it was supposed to do. The problem is that what it was supposed to do was build a superhero crossover around then-current Green Lantern continuity, which at the time focused quite a bit on the various ways in which the Guardians of the Universe were terrible at talking to women. Also, like almost everything else the company was doing at the time, Millennium was steeped in Cold War paranoia to a degree that seems almost comical in hindsight. The company was just drowning in the stuff in the period.

The house style for the few years after Crisis for so much of the line was a reflexive Saturday matinee realism - a Carolco Pictures view of the universe. It was reflected in a kind of consciously semi-ironic and knowing but also very gimmicky dependence on Ronald Reagan and the National Security Agency to show up as deus ex machina in a lot of different contexts. Reagan showed up randomly in post-Crisis comics in much the same way the Monitor had appeared across the Pre-Crisis line. Suicide Squad typified the mood, and wrings a great deal of energy out of it. But it didn’t make quite as much sense for a lot of other kinds of books, to whom the reliance on lots of scenes of angry bureaucrats having terse exchanges at the Pentagon often bequeathed a cardboard atmosphere redolent of straight-to-video productions.

There’s so much late Cold War shit in the Batman comics of the time, to a degree that is simply remarkable to contemplate. They basically just got to recycle all their worst 1950s Red Scare shit, with a patina of knowing irony and vaguely literary nods toward realpolitik, just like Hollywood did at the same time. With William Hurt, or someone else who could do that whole 1980s noble Hollywood Soviet thing DC put in like every one of their goddamn books.

God bless him, I don’t think Morrison could have written that kind of comic book if someone put a gun to his head. His Doom Patrol, and I suppose his Animal Man as well to a degree, but really very explicitly his Doom Patrol was just not a very friendly book to the other titles on the shelves around it - and not just the way that every aspect of military nationalism is derided during the book’s Pentagon arc? They put out a whole special to rag on the Rob Liefeld school of comic book creation - Doom Force, which is one of those things you always want to be a little bit better on reexamination than it actually is. It’s too canny an ape of the original to read as more than tedious in a large dose, and it’s a long story. But it also makes a bit more sense when you think about it in the context of the fact that the people whose work was satirized in Doom Force had worked at the same company not that long before. That makes sense. Especially when you remember that John Byrne’s Doom Patrol relaunch, twelve years after Doom Force hit shelves in 1992, was conceived and greenlit during that very brief period when Morrison was making his Marvel (his only work for DC during the period being under Vertigo).

Now it’s worth pointing out, the people who really got the picture regarding Image Comics, before anyone else, were the former members of the British Invasion, a few of whom did a number of projects for the company beginning pretty much right at Year Two. In nature the two constituencies made natural common cause. Alan Moore wrote a Violator limited series and had a sizable run on WildC.A.T.S. Those are not things anyone could ever have predicted based on the first year of the company’s output, and yet it made perfect sense. It also made perfect sense when the Image founders subsequently sued or fell afoul of the same British writers who they had so assiduously courted in the company’s early months. Just because they shared common cause didn’t make them in any way, shape, or form compatible spirits.

But we’re still in the very early 90s, Morrison’s Doom Patrol - comics I don’t really find myself wanting to engage with, or at least not on their terms. And after chasing them around my head for a few weeks I can only conclude, in this instance, that it’s kind of on me.

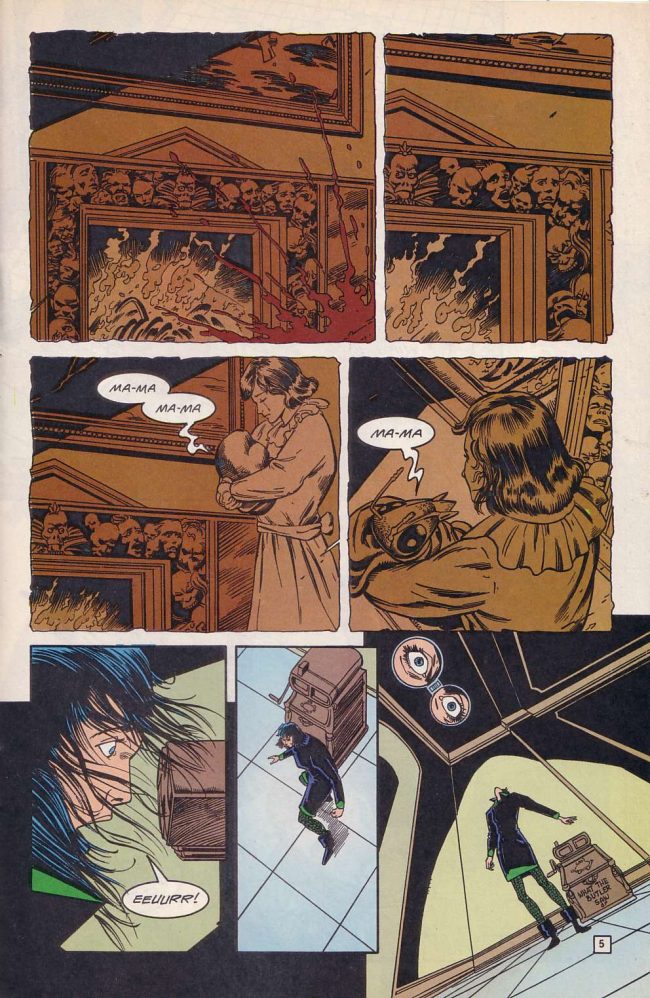

People really love these comics, have loved these comics consistently for thirty years. And yet, coming to it late, I’ve always been slightly disappointed - not necessarily in the story or Richard Case’s art, but more in terms of the characters. People love these guys, and yet I never really found myself bonding with them in the way I think is really necessary for these stories to hit the way they’re supposed to. You need to love Cliff Steele and Kay Challis for their storylines to come together. The big emotional beats only really work if you feel the peril and the frustration up close and personal.

That’s important, I think: there’s a lot going on here that only works if the reader is 100% emotionally invested, and without that investment it almost seems too easy to sit on the sidelines and pick things apart when they don’t hold together quite so easily. Too easy to point out the places where fashions have aged.

Sure, we can talk about The Brain and Monsieur Mallah - you knew we were going back to that. Perhaps it’s a small thing, the kind of thing that could be forgiven, coming right as it does at the heart of a large run filled with lots of other stuff. The Brain and Mallah only appear in one story, essentially as comedy relief, trying to break into the Doom Patrol HQ while the team is busy doing other stuff. But it also establishes them as lovers, which has remained firmly attached to the characters as they’ve gone forward through the years.

Doom Patrol #34 was published in 1990, and it’s certainly tempting to reread the story in a sympathetic light - after all, the idea of a snickering gay joke right in the middle of one of the most seminal runs of proto-Vertigo DC seems quite distasteful. But even the most somber, morbid, and misguided treatment of trans people in Sandman never quite got around to laughing at them. Whatever the original context was supposed to have been, I saw lots of jokes around Monsieur Mallah and the Brain in Wizard magazine over the next decade - and don’t think the context was Pride Month. In 1990 there weren’t a lot of queer characters in comics, any kind of comics, but there was Doom Patrol #34, a joke on its face that people just learned to accept as the years and decades rolled by. Danny the Street is a fan favorite, and I think the success of that character probably makes it easier to gloss over the early jokes.

Doom Patrol #34 was published in 1990, and it’s certainly tempting to reread the story in a sympathetic light - after all, the idea of a snickering gay joke right in the middle of one of the most seminal runs of proto-Vertigo DC seems quite distasteful. But even the most somber, morbid, and misguided treatment of trans people in Sandman never quite got around to laughing at them. Whatever the original context was supposed to have been, I saw lots of jokes around Monsieur Mallah and the Brain in Wizard magazine over the next decade - and don’t think the context was Pride Month. In 1990 there weren’t a lot of queer characters in comics, any kind of comics, but there was Doom Patrol #34, a joke on its face that people just learned to accept as the years and decades rolled by. Danny the Street is a fan favorite, and I think the success of that character probably makes it easier to gloss over the early jokes.

Does one sour issue spoil the whole run? Obviously not. But neither can it be ignored, either. And that’s why it’s important to remember, I think, that number - thirty years. Thirty years is a long time. I read parts of the Lee & Kirby Fantastic Four as a kid, before even the thirtieth anniversary rolled around for the World’s Greatest Comics Magazine, and it was quite obvious to me that those comics had been written in a different time by people who followed different standards: everyone was a sexist pig and Sue is absolutely useless for multiple issues at a stretch. It’s so normalized as to be inextricable from the actual stories and characters themselves. Does that primal chauvinism nullify the Lee & Kirby Fantastic Four? If it does for you, I can’t gainsay. You learn to read around that stuff or you don’t, as your enjoyment and conscience dictate.