In 1970, when I was eight, I counted among my favorite books the hilarious Mrs. Coverlet trilogy by Mary Nash. Written for young readers, the series -- While Mrs. Coverlet Was Away (1958), Mrs. Coverlet’s Magicians (1960), and Mrs. Coverlet’s Detectives (1965) -- unapologetically celebrates creative chaos. A big reason I loved these books was because of their evocative illustrations, drawn by Garrett Price (1895-1979) in his sixth decade of life.

A gifted visual storyteller, Price authored White Boy in the 1930s, a newspaper comic strip (a trilogy, actually, with three different names). Like the Mrs. Coverlet books, White Boy jounced young characters out of their normal lives to reveal them as funny, troublemaking, and occasionally heroic individuals.

Garrett Price’s White Boy was a color Sunday newspaper comic strip that ran from 1933 to 1936. The strip represents a high-water mark of the American newspaper comic, with striking visual storytelling and strong aesthetic values. The work is remarkable for the way it presents the expansive beauty of the American West and the subtleties of the natural world. More than any of this, White Boy is a quirky, highly personal work that makes you want to know more about its creator.

White Boy was Price’s only comic strip. How was it that he managed to create such an extraordinary, consummately crafted comic without being a career cartoonist? Part of the answer to this mystery lies in understanding that Price actually was a career cartoonist -- who mostly worked in other mediums besides comic strips. Part 1 of this essay explores the White Boy trilogy of comic strips. Now, we explore the life and full career of Garrett Price.

Early Years In Wyoming

Similar to Lyonel Feininger, another artist who created a short run of extraordinary Sunday newspaper comics (also for the Chicago Tribune, also artful and quirky), Price’s three years of White Boy comics represent a small part of a much larger body of work outside of comics. In Price's case, this body of work includes numerous magazine covers, panel cartoons, illustrations for books, magazines, and newspapers, and paintings. Most notably, Price was a key early New Yorker artist.

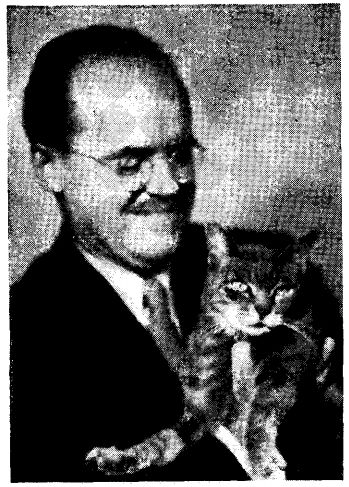

As far as can be determined, there is no comprehensive monograph or biography on Garrett Price available. Finding and unearthing dinosaur fossils appears to be only slightly harder than finding information on Garrett Price. “Wind from the West: The Life of Garrett Price,” Peter Maresca’s approximately 1800-word essay included in the newly published White Boy in Skull Valley (Sunday Press, 2015), is a significant contribution, providing a solid, insightful portrait of Price. This Comics Journal article augments Price's story with some additional information and art.

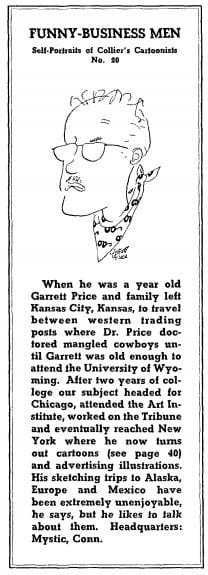

From Peter Maresca’s introductory biographical essay, we learn that William Garrett Price was born in Bucyrus, Kansas in 1895 and grew up in Saratoga, Wyoming. As a boy, Price accompanied his father, a well-read country doctor and prominent public official, on many far-flung house- and ranchcalls around the state. In 1944, Price recalled: "When I was one, my parents started dragging me from trading post to trading post. My father doctored mangled cowboys in Wyoming, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Idaho." (1)

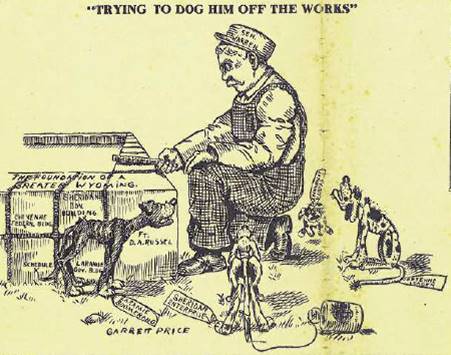

Price’s first published cartoon, an editorial effort about local politics, appeared in the Saratoga Sun on August 29, 1912 (it is cited and reprinted in Peter Maresca's White Boy in Skull Valley). It is a crudely drawn cartoon with some winning depictions of skinny dogs, but otherwise showing nothing of the mastery to come.

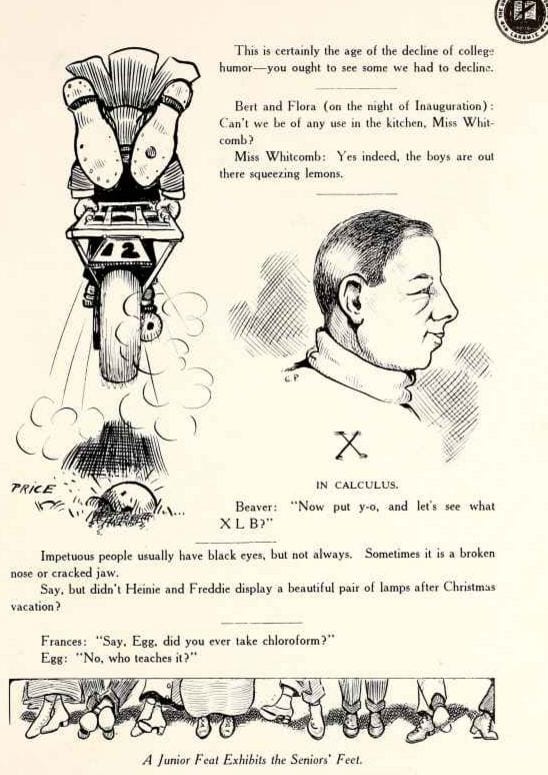

From 1912 to 1914, Garrett Price attended the University of Wyoming in Laramie, about a hundred mile's journey from his home. Price's class was small, about 20 students. He was younger than most of his classmates. In his 1915 class photo, he is considerably smaller than his classmates and sits awkwardly next to co-eds who tower over him.

In his two years there, Price became a member of the Pen Pushers, a journalism club. He also contributed a number of cartoons for the 1914 WYO yearbook. Years later, the yearbook's editor, Agnes Wright Spring, recalled Price:

"As I remember him, he was only a freshman. He was small and wore knee breeches. But we all recognized his drawing talent and sought his help with the WYO."(2)

The 1914 WYO yearbook included in its forward a shout-out to Garrett Price: "Especial thanks are rendered to... Mr. Garrett Price, who has so efficiently aided us with cartoons and drawings of high quality." Though Price's yearbook cartoons are clearly the uneven work of a novice, one can see a great deal of growth from the 1912 Saratoga Sun cartoon.

Price is mentioned a couple of times in the next year's WYO yearbook, but by the time that edition had come out, Price had left for greener pastures: the Chicago Institute of Art. There, Price befriended James Geraghty who would become art editor of the New Yorker from 1939 to 1973. Price also made lasting friendships with fellow future New Yorker cartoonists and cover artists Alice Harvey and Helen Hokinson, with whom he shared studio space in the Tower building on North Michigan Avenue, one of the tallest buildings in Chicago. (3)

At The Chicago Tribune

Around 1916, Price landed a position in the art department of the Chicago Tribune and embarked on a 63-year career as a cartoonist, illustrator, and painter.

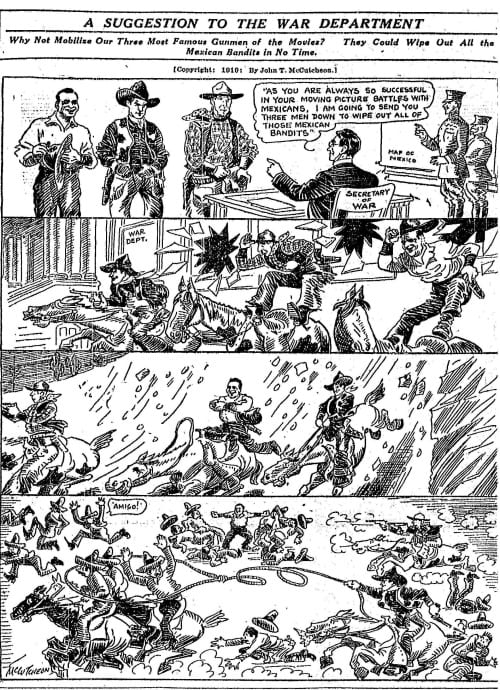

At that time, the star cartoonist on the paper was John T. McCutcheon, one of the greatest pen-and-ink stylists to work in American newspaper cartoons and comics in the twentieth century. For many years, the front page of the Tribune featured a daily cartoon by McCutcheon, printed “above the fold.” A 1918 biography of Garrett Price’s father provides this information that suggests McCutcheon’s influence:

“He [Price] is a young man of extraordinary talent as a pen illustrator and cartoonist and his work on the Chicago Tribune has gained him wide fame and publicity. He works under the direct supervision of McCutcheon, who is perhaps the best known cartoonist of America.” (4)

Price may have been influenced by McCutcheon’s trademark strategy of varied techniques. When McCutcheon died in 1949, the Chicago Tribune praised his tendency to vary styles: “John could not have been the cartoonist he was if he had not been a skillful and ready draftsman, the master of three or four matured styles.” (5) Looking back on Garrett Price’s career, one could say the same thing in regards to both his draftsmanship and his use of different styles, White Boy included.

Beyond pen techniques, Garrett Price very likely learned from McCutcheon what was at the time a new kind of cartooning, not political or humor cartoons, but something gentler and richer. As the Tribune put it:

“John McCutcheon was the father of the human interest cartoon… He was the first to throw the slow ball in cartooning, to draw the human interest picture that was not produced to change votes, or to amend morals, but solely to amuse, or to sympathize. The reader felt these qualities in McCutcheon’s work. The reader said to himself, ‘This man understands me.’ McCutcheon’s cartoon of the boy away from home at Christmas time solaced many a homesick lad. The heart of the soldier who didn’t get a letter was consoled by McCutcheon’s cartoon. The nation, the whole nation, understands and loves his ‘Injun Summer.’” (6)

(For more on John McCutcheon, see R.C. Harvey’s thorough Comics Journal essay here)

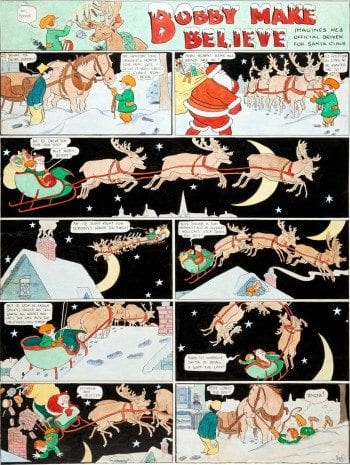

Frank King also worked at the Tribune with Price, his Bobby Make-Believe and The Rectangle features appearing regularly. King’s Gasoline Alley started in 1918. It doesn’t seem too far-fetched to suggest that King’s humanitarian, gentle, kid-oriented content, combined with his inventive formal experiments may have also been a model to the young Garrett Price. Both artists notably celebrated nature in their art. Peter Maresca has noted that "Frank King, creator of Gasoline Alley, was Price's closest friend at the paper." (7)

It's possible that Price may have also been influenced by yet another Tribune’s staffer: Penny Ross, author of the graphically inventive Sunday comic, Mama’s Angel Child. While White Boy was not as baroque or dense as Ross’ strip, perhaps the idea of a comic strip imbued with a painterly spirit had an influence on Price.

Price encountered many great artists and writers at the Tribune, including Ring Lardner, Sidney Smith (Old Doc Yak, The Gumps), and the illustrator Herbert Stoops, who is cited as Price’s mentor in at least one source (8).

In the summer of 1917, Price joined fellow Tribune artists John T. McCutcheon, Ring Lardner, Frank King, Sidney Smith, and others in a charity baseball game for the Red Cross held at Cubs Park. They played against the artists of the Chicago Herald, including Popeye’s future creator, E.C. Segar, who pitched the game’s seven innings and gave up most of the runs in the sixth and seventh.

Segar also nearly knocked himself out when, in a slapstick moment worth of Thimble Theater, instead of sliding onto a base, he ran straight into the outstretched fist of the opposing player, who had just caught the ball. Long before that comic occurrence, Ring Lardner managed to get himself thrown out of the game in an early inning. After similar misadventures, the game was called to a premature halt by the umpire, showing mercy on the Herald staffers, who only had three runs to the Tribune’s 19. The next day, the Chicago Tribune reported the umpire had felt, “the Herald artists had drawn enough punishment.” Garrett Price scored one run. I smile when I think of the diminutive artist racing around the diamond that sunny afternoon nearly 100 years ago, cheered on by his fellow cartoonists. (9)

In his later years, Price would not only remain good friends with some of the artists he met in Chicago, but he would also share a community with them in Westport, Connecticut which was home to 17 New Yorker artists between 1925 and 1989. (10) Price's old mentor, Hebert Stoops was his neighbor.

After absorbing all this early mentorship and inspiration, Price’s course as a leading artist of his time was laid out . First, however, he had a side navigation to make. He joined the Navy.

World War One - A Cartoonist Fights With His Pen

With World War One in its fourth year, and the United States officially entered for just about a year, Price was trailing in the wake of a fleet of volunteers. He was the 219th Tribune employee to enlist in the service of his country, and the fifth from the art department.(11)

Fellow cartoonist E.E. Lowry, returning from the front, submitted the following humorous letter in 1918, with deliberate misspellings, about Price to Cartoons Magazine, addressed to the editor (“Ed”):

“I left that picture of Garrett Price on your desk and caushioned the girl not to swipe it but when she took a look she said it would be perfectly safe anywhere so I guess you got it all right, o. K. You see Ed, the reason I want this picture back is not so much because I’m a big grouch or on account of its good looks but this bird quit a swell job in the Chicago Tribune art department to go out and tie himself up at the Great Lakes training station, so you see, if he ever becomes a hero and the city Ed. is running around some night half crazy for a picture, I can flash this one on him.” (12)

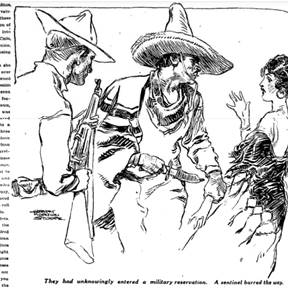

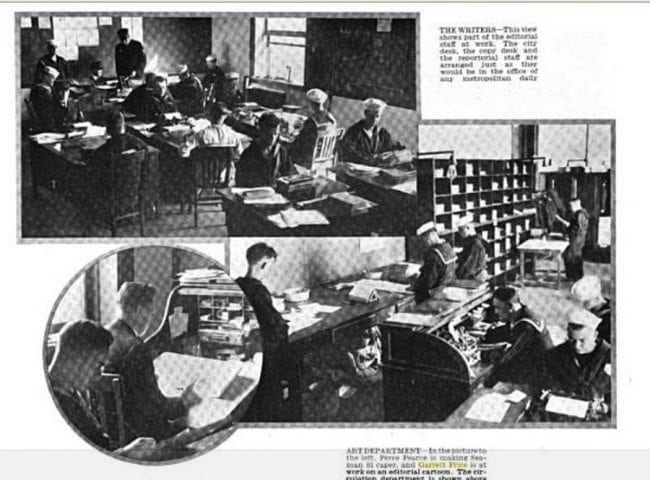

Despite Lowry’s hopes for Price’s heroism, after basic training at the Great Lakes Naval Station, Price received a relatively safe assignment in the art department of another newspaper, the Great Lakes Navy Bulletin. The December 1918 issue of The Recruit: A Pictorial Naval Magazine ran an illustrated feature on the publication (complete with a photograph of Price at his drawing board), stating that “In the art department with [Perce] Pearce is Garrett Price who draws powerful cartoons dealing with current events and whose work is reproduced from The Bulletin by scores of newspapers and magazines.” Perce Pearce drew for The Bulletin the comic strip Seaman Si, a popular series among Navy men of the time.

According to Maresca’s Sunday Press essay, Price created a Bulletin political cartoon every day for a year while at the same time contributing to the Chicago Tribune and even providing humorous verse to the Chicago Daily News.

As is often seen in the early careers of notable illustrators and cartoonists, Price had quickly achieved a full head of steam and was plowing through reams of work. Also in 1918, he contributed illustrations to Outdoor Recreation.

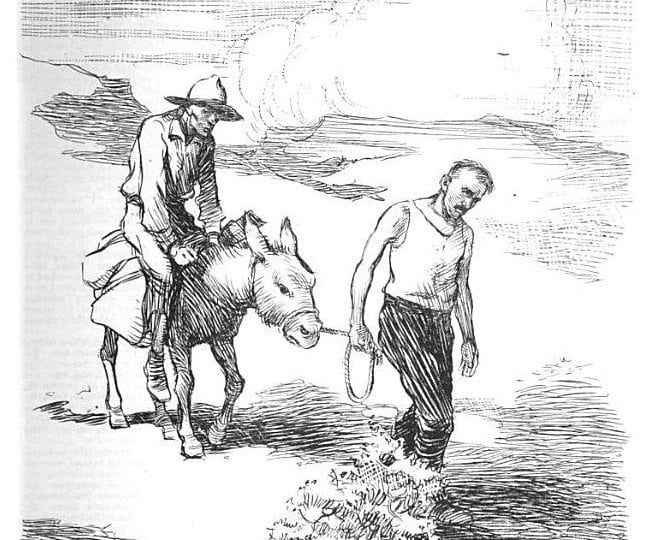

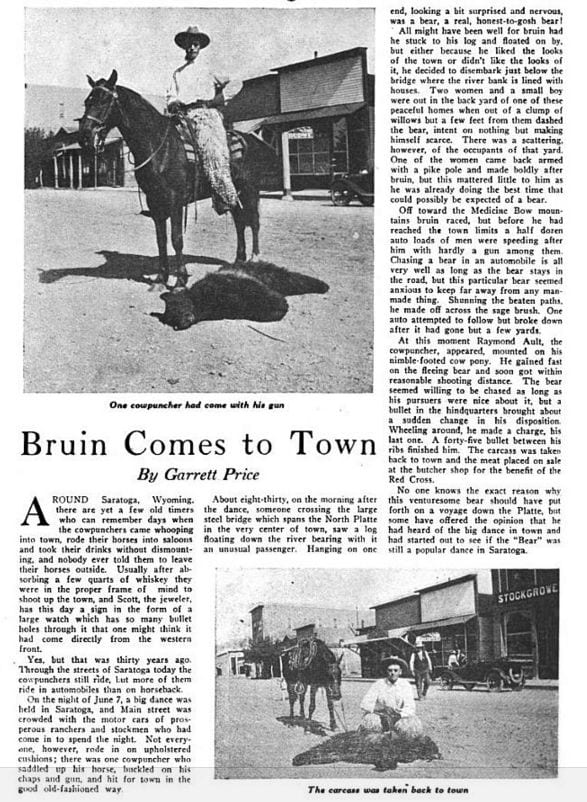

Price also wrote a rare article for Outdoor Recreation, “Bruin Comes to Town,” a short, humorous report about a drunk cowboy shooting a bear in Price’s home town of Saratoga, Wyoming that reads like a text description of a late-run episode of White Boy.

Back At the Trib - Evolving Into a Master Illustrator

In the 1920s, Price was back at the Chicago Tribune, where he provided numerous illustrations for the paper’s Sunday arts supplement.

He used a surprising range of techniques, from densely hatched landscapes to impressionistic moments of intense action, to flat comic line drawings. A rich variation of visual approaches is a hallmark of Price’s work, and of White Boy. Collier’s Weekly noted: “If you watch his work, you’ll notice he frequently changes his technique, switching from pen and ink to wash to crayon, changing his style in the process – to keep from going stale, he says.” (13)

Price’s illustrations from this period demonstrate a rapidly growing mastery and, with their variations, are far from being “stale.” In some cases, Price used a blizzard of barely contained pen strokes to shape a city scene. In another issue, Price’s illustrations are composed of bold, thick crayon lines.

For the famous performer, playwright, and composer George M. Cohan’s (“Yankee Doodle Dandy”) regular column, Price usually employed a clear line technique, dense with details and caricatures, but no hatching or shading.

Branching Out As A Freelance Illustrator

Between 1924 and 1926, Price made several trips to Paris, where he studied art and added to his quiver of styles and techniques. (14) At the Tribune, Price was a writer as well as an artist. Having grown tired of the relentless demands placed upon a newspaper staff artist, Price moved to New York in 1925 to become a freelance illustrator. (15)

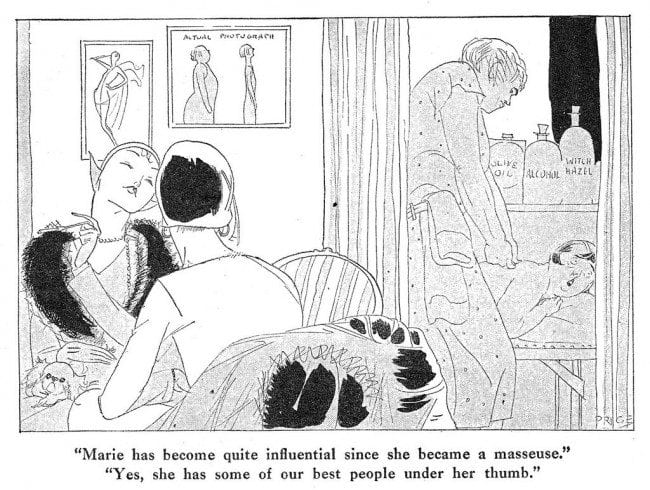

In short order, Price found regular outlets for his work at some of the nation's top magazines. Notably, he created many cartoons for the original Life magazine from the mid to late 1920s, and became a regular cover artist, as well. Price's work had assumed a new sophistication in both style and content. A blogger on the art and cartoons of Life gave an insightful description of Price's cartoons for the magazine:

"His crisp, unweighted lines, spotted blacks and use of half-tones as a design element rather than a rendering tool complemented the more modern approach to cartooning and illustration that had been gradually achieving dominance over the look of the magazine for at least a decade." (16)

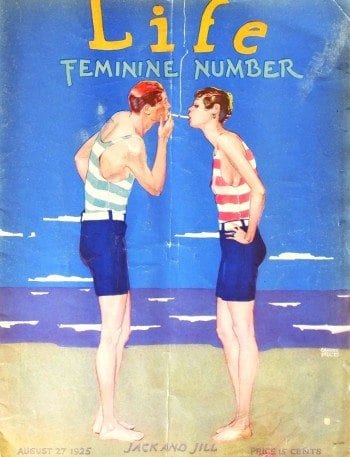

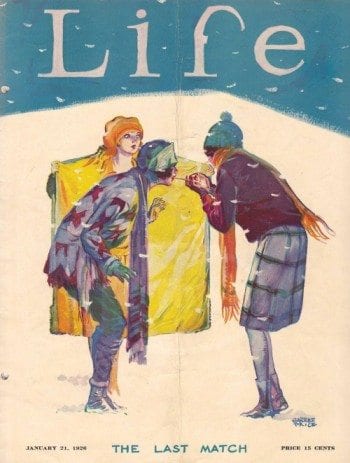

In addition to penning numerous cartoons and short humor pieces for Life, Price also painted twenty impressive covers for Life (17), depicting 1920s flappers and their handsome, lantern-jawed paramours in bold, eye-catching designs. A few years later, the sexual undercurrents of his Life work would have a faint echo in the tender young love between the protagonists of his White Boy comic strip. For an early Life cover, Price used a slightly risque "cigarette kiss" concept.

A few months later, Price rang a variation on his cigarette concept -- moving from the sunny beach to a mound of snow. His use of color, particularly the yellow interior of the coat used to block the wind, is striking.

A few months later, Price used color again to create a flirtatious cover that no doubt caused newsstand browsers to look twice.

Price's use of color to suggest space and story grew by leaps and bounds in the mid-1920s. By 1928, he could masterfully indicate a stolen kiss in a dark movie theater with a broken mass of black paint. Price's Life cover for the 1928 issue works as both a cover and a cartoon, with a short caption. The gag is that the couple's declaration of love provides the sound track for the silent newsreel depicting world leaders. It's a work that is both funny and artistic -- values that Price would soon put into his White Boy comic strip.

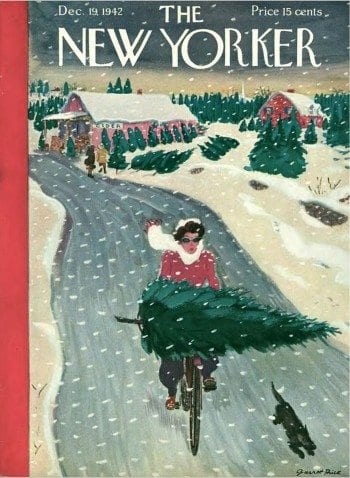

In addition to a regular account at the well-established Life, Price also sold a cover in 1925 to a brand new start-up magazine called The New Yorker. It depicted blobby skyscrapers of the city melting in the summer heat -- in a style unlike anything Price had done before.

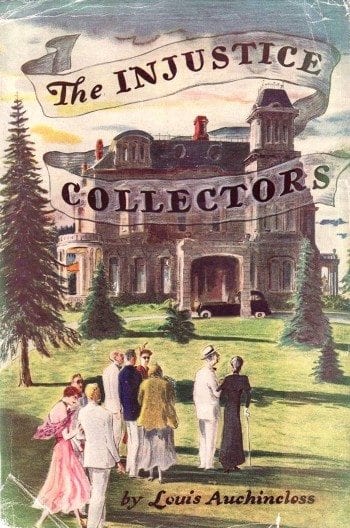

In addition to his magazine work, Price also got some book cover jobs, such as his Doubleday dustjacket art for the popular Western pulp writer Charles Alden Seltzer's The Raider. This is the perhaps the first known instance of the Wyoming-born Price depicting Western Americana in his professional work.

White Boy - Price's Only Comic Strip (1933-36)

By the early 1930s, Garrett Price had established himself as a leading popular artist of his time. He had mastered numerous techniques and was able to create entertaining consumer art with depth and artistic merit. Price's growth may have caught the attention of his former boss, "Captain" R.W. Patterson, at the Chicago Tribune. Patterson invited Price to create a new feature for his color Sunday comics supplement. For this, Price drew on his memories and knowledge of the mythic West, and created the singular White Boy. Price used his full quiver of rendering techniques, but in a stripped down style that was as bare and beautiful as the American desert. It was the kind of work that only a seasoned and gifted artist could achieve.

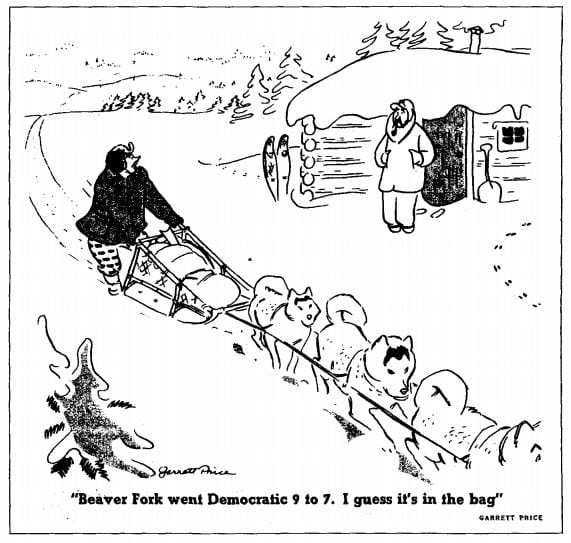

After three years, and as many names and concepts, Price's comic ended. Price had continued his freelance work for the New Yorker, accomplishing notable work there (including a rare, double-page cartoon), as well.

After three years, and as many names and concepts, Price's comic ended. Price had continued his freelance work for the New Yorker, accomplishing notable work there (including a rare, double-page cartoon), as well.

Perhaps the workload was too much and Price, or the Chicago Tribune syndicate, opted to end his comic, which seemed to have lost the trail, anyway.

Cover Artist, Illustrator, Gag Cartoonist

From the 1940s through the 1960s, Price created covers, cartoons, and illustrations for numerous magazines, including Collier's, College Humor, The Saturday Evening Post, Harper's Bazaar, Good Housekeeping and Esquire. He varied his media and techniques to suit the different needs of the editors. In 1946, he created a standout cover for Colliers, lushly depicting a circus sideshow that also functions as a wordless gag cartoon.

The 1930s and 1940s were a booming time for magazines, which meant that print advertising was also enjoying a golden age. There was plenty of work for the established cartoonists, and it's no surprise to find that Price's cartoons were used to sell everything from irons to telephone service.

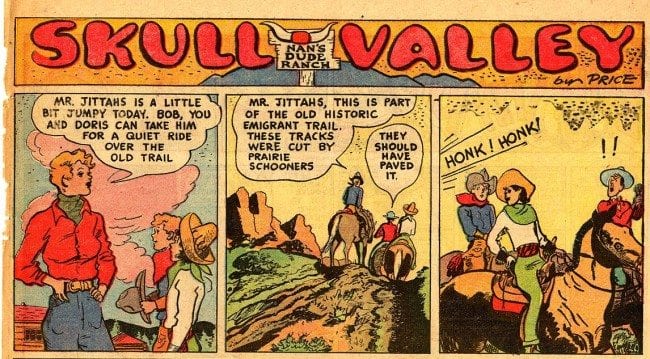

In one ad, he used a sexy, comical western character that could have ridden off the pages of Skull Valley, the third, dude ranch, version of his White Boy comic strip.

Throughout the 1940's Garrett Price cartoons could be seen in various magazines (not to be confused with the cartoons of John M. Price, who also published during the 1940s).

In his 1940s work, Price began to develop a creative fulcrum between depicting rural, western subjects and scenes of city people escaping into nature. His New Yorker covers told little stories of determined, goofy city people enjoying rural life, somewhat like the essays written by New Yorker humorist E.B. White about his experiences of quitting his job at the magazine in 1938 buying and running a farm in One Man's Meat, experiences that also inspired his children's book, Charlotte's Web.

Around 1940, Price and his wife Florence -- whom he had married in 1928 -- settled in Westport, Connecticut, buying a summer home a few years later at the nearby Mystic Seaport. (18) A 1944 profile in Collier's described the comfortable life Price had settled into: "What Price likes is just what he is doing -- living quietly with his wife in Westport, Connecticut, doing a lot of carpentry, a little gardening, and a lot of cartooning."

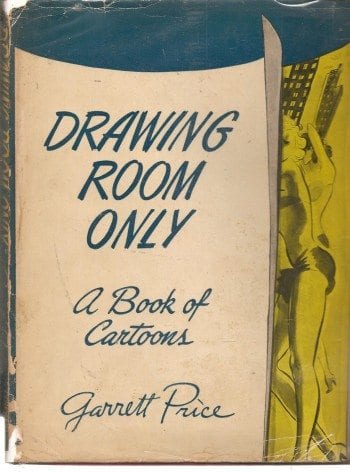

In 1946, Drawing Room Only, a collection of Price's cartoons was published. It was the only collection of his cartoons published in Price's lifetime.

Price and his wife also took a lot of trips in the 1940s and 1950s. In some of his Skull Valley strips, Price depicts crass tourists visiting a dude ranch with an edgy comedy. In 1944, he used a similar subject for a New Yorker cover.

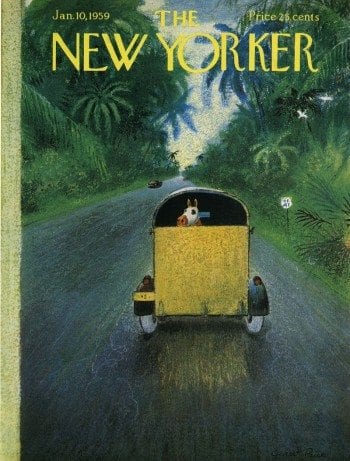

Although he never worked professionally in sequential graphic storytelling after White Boy, much of Price's later work embraced visual storytelling and the themes of his comic strip. A 1959 cover showed a race horse on a highway. He looks longingly out of his trailer, masked and confined, at the forest around him. In White Boy, horses run free at first and then, by the end of the series, they are corralled and used as mounts for city slicker tourists to ride.

Price and his wife enjoyed a happy life living in the artistic community of Westport. They had no children, but were close to their family. Peter Maresca wrote:

"Florence helped Garrett maintain his reputation as an affable and gentle man with a soft sense of humor and a heart that was open to life..." (19)

In his later years, Price continued to create covers for the New Yorker. His work graced the covers and interiors of several books, including Mary Nash's Mrs. Coverlet series.

In his last years as a professional cartoonist, Price created a cartoon gag series, Price Tags, for the Westport News. (20) When his wife died from lung cancer in 1973, Price was heartbroken and despondent. He did little professional work afterwards. His final New Yorker cover appeared on July 29, 1974. Price died August 8, 1979.

Price's obituaries and subsequent capsule biographies barely mention White Boy. In 1977, Bill Blackbeard and Martin Williams reprinted a couple of spectacular White Boy pages in their Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comics, inspiring an interest in the strip that found full bloom in late 2015, when Sunday Press released a complete collection of the strip, White Boy in Skull Valley.

The full measure of Price's work and artistic accomplishment has yet to be taken. He was a gifted artist who could have made a life as a gallery painter, but instead worked in popular print media, including for a brief time, comics, where he created one of the most affecting strips I have ever read. By all acounts, Price was a modest, quiet and introverted person -- but his work speaks boldly to me, with humor, depth and humanity. Price's physician father worked on "mangled cowboys," and Price, with his understated artistic explorations of the clash between old and new, worked on our mangled culture.

_________________

Notes:

(1) "Cartoonist Garrett Price" (Collier's, October 7, 1944).

(2) Agnes Wright Spring, Near the Greats (American Traveller Press, 1981), 126.

(3) Garrett Price obituary, The Hour, August 9, 1979.

(4) History of Wyoming, Volume III (Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1918).

(5) Editorial, Chicago Tribune, June 11, 1949.

(6) Ibid.

(7) Peter Maresca, White Boy in Skull Valley (Palo Alto: Sunday Press, 2015).

(8) The Hour, August 9, 1979.

(9) John Alcock, "Artists Suffer for Red Cross: 'Tribunes' Defeat Heralds 19-3," Chicago Tribune, May 28, 1917.

(10) Meg Learson Grosso, “When The New Yorker Moved to Connecticut,” Connecticut Magazine, April 2, 2014.

(11) Chicago Tribune, July 9, 1918.

(12) Cartoons Magazine, September 1918.

(13) Collier's, February 12, 1944.

(14) Maresca, White Boy in Skull Valley.

(15) Ibid.

(16) "Life Drawing Sunday IX: Garrett Price" (Filboid Studge blog, August 20, 2006).

(17) Maresca, White Boy in Skull Valley.

(18) Ibid

(19) Ibid

(20) The Hour, August 9, 1979.