Let’s talk about real-time storytelling in superhero comics.

Let’s talk about real-time storytelling in superhero comics.

More specifically, let’s talk instead about copyright, media consolidation, and the future of artistic expression through the lens of real-time storytelling in superhero comics.

What's going to be discussed here has a significant degree of 'the way things used to be' about it, but let's put our cards on the table: Comics have always been a profit-making enterprise. The idea that there was ever a time when commerce wasn't driving the Batmobile is ignorant at best and willfully naïve at worst. You could even make the argument that things are better now that they've ever been; the war between art and commerce still has a clear winner and a clear loser, but the number of people who want to make comics, and are doing so with relatively little concern for their own remuneration, is higher than ever. But that in itself is part of the problem, and that problem is one of possibilities.

Before the powers that be at Marvel and DC struck upon the idea of continuity – which, to be clear, was absolutely a marketing move, one meant not to elevate the art form but to sell more copies of comic books – what we now think of as their multifaceted fictional universes were just a collection of unrelated stories with nothing more than their main characters showing any form of consistency. It was an episodic, and not a serial, form of storytelling. And that’s fine! But when Stan Lee, influenced by soap operas, decided to impose an external framework on them as part of his ongoing plan to make them palatable (and thus salable) to older kids, he introduced an element of formalism the medium had previously lacked. Formalism is a straitjacket that opens up possibilities in the guise of restrictions; ask any Oulipo you happen to meet. The result was that readers took to the stories like never before, suddenly seeing in an otherwise childlike form of entertainment a code to be cracked, a canvas to be filled, a key in search of a keyhole.

Prior to the 1980s, right before the institution of annual crossover events that were intended to clean up the DC and Marvel continuities but actually ended up wrecking them beyond repair, a certain tendency of comics fandom (small to be sure, but definitely vocal in its opinions) found delight in playing around in the multiversal sandbox the companies had created. Many of these first-generation fans of the new Way of Things, much like their counterparts in fantasy and science fiction fandom, would become a new wave of comics creators, and some (Roy Thomas is the first, but not the last, name to conjure with), actually found employment with the Big Two and were able to make their play into something tangible.

Even for those who weren't so lucky (or so talented), the possibility seemed to be there; even if they didn’t have the actual ability to influence these stories, it felt like they could. People who would be forever kept out of the process of creation by circumstance, prejudice, or even mere lack of talent still had a certain sense of control over the medium, gripped by the Emersonian recognition of their own alienated thoughts in a work of simple genius. There was a sense of physical as well as philosophical possession as thousands of readers began to realize that this was an art form that, in a meaningful way, belonged to them, and that they had as much right to tell stories with these long-established characters as did anyone else.

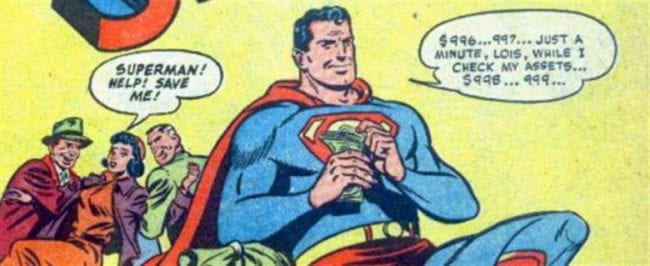

But the writing was on the wall, even back then. In any form of narrative storytelling with an element of continuity, there was the built-in problem of age: What happens to the world you’re trying to build when the people who live in it get older? Here is where commerce and art butted heads the most painfully: While readers were more than willing to take a chance on new characters, or throw old ones into extreme situations from which they might not ever emerge, the corporate gatekeepers were typically risk-averse. There was no reason that an alien like Superman or an immortal like Wonder Woman had to grow old, but Batman was fair game, and no matter how good a story a writer might come up with, nobody was willing to screw the pooch by killing him off. You don’t slaughter that golden goose.

But the writing was on the wall, even back then. In any form of narrative storytelling with an element of continuity, there was the built-in problem of age: What happens to the world you’re trying to build when the people who live in it get older? Here is where commerce and art butted heads the most painfully: While readers were more than willing to take a chance on new characters, or throw old ones into extreme situations from which they might not ever emerge, the corporate gatekeepers were typically risk-averse. There was no reason that an alien like Superman or an immortal like Wonder Woman had to grow old, but Batman was fair game, and no matter how good a story a writer might come up with, nobody was willing to screw the pooch by killing him off. You don’t slaughter that golden goose.

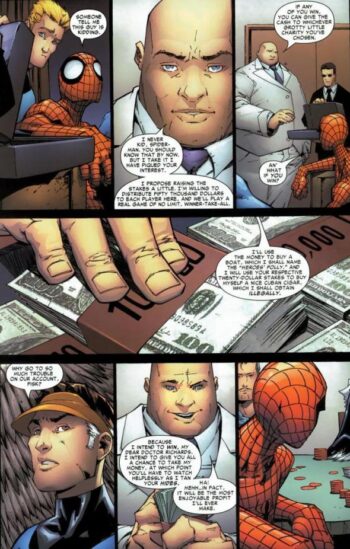

By the dawn of the crossover event, the die was cast. Crisis on Infinite Earths and Secret Wars, whatever their artistic problems, had opened up the possibility of mass permutation and change, creating the potential for disruptions that could yield fertile storylines and room for daring artistic choices to be made. But it quickly became apparent that this would never come to pass. The properties were just too valuable to fuck with. Once it became clear that the editors had a mandate to change things just so much and not a hair more, comics settled into a storytelling malaise from which it has arguably never recovered. Real time is dead; even continuity has become a bad word, and while it’s fashionable to blame that on fanboys who can’t handle ambiguity, the real culprits are corporate interests who want an audience of tens of millions of blank slates. Institutional memory is the enemy of marketing; a fan base that demands respect for the natural flow of storytelling is not a fan base who will happily settle for the whole thing being blown up every few years to sell more merchandise.

Though we’re accustomed to thinking of continuity and consistency as mere aesthetic decoration, it goes a lot deeper than that. The purchase of Marvel Comics by the Disney corporation means that the universe of art (now reduced to the world of content provision) is smaller than it has ever been, while the audience is just as much larger. With DC owned by Time-Warner, BOOM! Studios controlled by Fox, Valiant snatched up by DMG, and Dynamite and IDW both specializing in licensing other company’s intellectual property, the number of fictional properties in comics that are now in the hands of just a few companies is greater than ever. This mirrors what’s going on in the entertainment industry at large, as increased consolidation puts franchise after franchise at the whim of a handful of CEOs.

Why does this matter? If you’re not a continuity creep, what difference does it make? If the number of characters is the same, what difference does it make who’s signing the paychecks of the people telling these stories?

Why does this matter? If you’re not a continuity creep, what difference does it make? If the number of characters is the same, what difference does it make who’s signing the paychecks of the people telling these stories?

It matters for a lot of reasons. Primarily, we have seen, particularly in the film and television industry, the way that increased corporate control flattens out the artistic landscape. Big businesses are big not because they’re audacious and take big gambles; they’re big because they fiercely protect their assets and hate doing anything risky. There’s a reason that Marvel movies are released on such a punishing schedule, and there’s a reason that they have increasingly come to all look the same: the company is sinking hundreds of millions of dollars into these properties, and it is unthinkable that the men in the corner offices will not see a return on those investments. We tend to lose, in the fog of choice, our sense of where the money goes, and money is what puts product on the shelves and on the screens.

Amazon didn't spend $250 million just for the rights to a Lord of the Rings series because they have a great idea for telling an amazing story; they did it to keep anyone else from getting those rights. Apple, likewise, didn't spend a similar slice of a billion on Isaac Asimov's Foundation because fans were demanding they do so; they did it to have something to throw at Amazon's LotR series. Marvel doesn't have a bunch of TV shows on Netflix because it represents a natural home for their demographic; they're there because it was available territory for them to occupy before someone else got there. These price tags mean something. The more big companies rely on the necessity, rather than just the possibility, of success because of the vast sums they sink into familiar properties, the less they'll be willing to take a risk on something, someone, anything that might not pay off. Every dollar sunk into the perpetual revivification of the recognizable is a dollar that won't go to the new and strange, to the untried and risky business that once made the industry so exciting. And the fewer companies control the means of producing media, the fewer places there are for creators to go where they stand any chance of making a living, let alone an impact.

So we’ll keep seeing the same thing, over and over, until one of the tentpoles inevitably collapses and the producers take a big enough bath to reconsider their approach. This is a process that we are seeing in practically every industry, but especially those on the ‘creative’ side; rather than attracting talented new artists and giving them the freedom to tell their stories with these characters, they are being made into interchangeable elements in a content machine. We may praise the decoration of the firmament with stars and directors who are less uniformly white, straight, and male, but we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that they are getting lower in a sky that’s getting awfully crowded and losing its shine. And once you've started taking those big paydays, you're not likely to go back to what got you the job in the first place; there's growing evidence that letting maverick talents into the sandbox is actually harmful to the model the studios are trying to create.

So we’ll keep seeing the same thing, over and over, until one of the tentpoles inevitably collapses and the producers take a big enough bath to reconsider their approach. This is a process that we are seeing in practically every industry, but especially those on the ‘creative’ side; rather than attracting talented new artists and giving them the freedom to tell their stories with these characters, they are being made into interchangeable elements in a content machine. We may praise the decoration of the firmament with stars and directors who are less uniformly white, straight, and male, but we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that they are getting lower in a sky that’s getting awfully crowded and losing its shine. And once you've started taking those big paydays, you're not likely to go back to what got you the job in the first place; there's growing evidence that letting maverick talents into the sandbox is actually harmful to the model the studios are trying to create.

This is likely to become especially pronounced with the entrance of Disney into the picture. Longtime masters of calculated and infuriating management of its intellectual properties, its entrance into ever wider fields of entertainment has seen a predictable uptake in lawsuits, adverse working conditions and contracts, and copyright extension lobbying designed to crowd competition out of the market. Warner’s reputation isn’t quite as malignant, but it’s not for lack of trying, and the brutally clumsy way in which Marvel and DC have been managed over the last decade or so, from financial incompetence to acting as a helpless feeder for the movie business and from shielding sexual harassers to making gunshy and tone-blind decisions about what to do next, are likely to get an awful lot worse and not better.

We can argue ad infinitum about why mainstream comics are in such a precipitous decline at a time when interest in them and money to be spent on them are at record highs. But it can’t be argued that consolidation of intellectual property will be anything but a disaster, or that it will benefit anyone in the industry other than the moneymen and bosses, and a handful of lucky creatives who are smart enough to do what they’re told. Commerce and art are in no way incompatible, but survey the landscape of mainstream comics: look at their intense aversion to risk or change, their sheer terror at employing anyone who might rock the boat, the way they micromanage everything and under-license nothing. It’s not new to see superheroes used to sell cheap shit, but in the past, there was always a there there, a pretext for telling these stories outside of the need to hit the Chinese market at just the right time of the year, a sense that these characters were alive outside of their existence as names to be assigned to an actor, who would then appear in the comics looking like themselves, until age or contract negotiations demanded a new caricature.

Comics have always existed in uncomfortable proximity to the people who love them. Intellectual property consolidation isn’t a recent development, but it has recently come so quickly and in such force that the fandom that sustained the art form through its first century could not possibly exert any control over it now. While comics were always a business, they were at least under the watch of people who felt they had some kind of responsibility to their leadership. Now they are a commodity, like oil, or like electricity, or like the news, and it makes as much sense and gets as many results to complain that corporate ownership is choking out its roots as it would to complain that bottled water is too wet. In late capitalism, the laws of supply and demand are flipped, and our job is no longer to criticize or contextualize, but merely to consume. The goal of every company is to be a monopoly, to ignore, as blood-drinking space monster Peter Thiel once said, the “tiny little door that everyone is trying to rush through”, and instead “go through the vast gate that no one’s taking”.

Comics have always existed in uncomfortable proximity to the people who love them. Intellectual property consolidation isn’t a recent development, but it has recently come so quickly and in such force that the fandom that sustained the art form through its first century could not possibly exert any control over it now. While comics were always a business, they were at least under the watch of people who felt they had some kind of responsibility to their leadership. Now they are a commodity, like oil, or like electricity, or like the news, and it makes as much sense and gets as many results to complain that corporate ownership is choking out its roots as it would to complain that bottled water is too wet. In late capitalism, the laws of supply and demand are flipped, and our job is no longer to criticize or contextualize, but merely to consume. The goal of every company is to be a monopoly, to ignore, as blood-drinking space monster Peter Thiel once said, the “tiny little door that everyone is trying to rush through”, and instead “go through the vast gate that no one’s taking”.

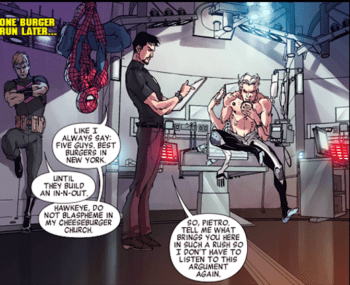

It was once true – if not very true, at least not false – that comics came to us through that tiny little door. And we could see just far enough inside to think that there were stories in it that hadn’t been told yet, and we could be a part of telling them. Sometimes one of us actually slipped through that door and came out on the other side. We may still have been bombarded with content all day, but it felt like at least something of a two-way street; if you see Spider-Man enough times, you might just get to thinking that in a very important and meaningful way, he belonged to you, as much as he belonged to whatever limited-liability corporation owned the rights to him. If Superman's adventures came to you in a comprehensible way that reflected something like your own experiences, delivered at the pace of life and not a marketing schedule, and weren't just narratives crafted to satisfy foreign markets featuring drawings pattered after whoever was playing him on the big screen at the moment, he became something more real than a name in a corporate portfolio.

And that was important. It meant that what stories got told about him were important, and that what context they appeared in was meaningful, and there was at least the pretense that we were part of the process, and not just the end point of a delivery system. Even if comics have always been a business -- and they absolutely have -- it debases the mind and ruins the spirit to be constantly reminded that you were just being sold an intellectual property, just as it does to be constantly reminded that you are employed at the whim of some distant, uncaring CEO and not a human being who must work to earn a living.

There’s no need to go into the toxic history of corporate consolidation in literally every field of human endeavor; it’s easy enough to learn and entirely omnipresent. With each incident of a huge company buying up the properties of a smaller one, that door gets less tiny; the door is bigger every day, but it only opens one way, and we’ll never get through it. Handing over the stuff from which our culture is built to an unanswerable board of billionaires won’t just kill real time and continuity and diversity of perspective and other charming little manifestations of the art of comics; it will have the same effect on our culture that turning our political system over to lobbyists and bankers has had on our democracy. It turns the naïve gatekeeping of fans into the soulless gatekeeping of accountants, and makes a vast gate from which nothing we truly asked for will ever emerge. It weaponizes copyright and turns intellectual property into a prison. If you want to know the future of comics, don’t look at software; look at pharmaceuticals.

We’ve been trained to expect this, and to mount no protest, because America, the nation of temporarily embarrassed millionaires, still assumes that more money means more opportunity. But the small door is closed and the vast gate will never open. The war between art and commerce has moved from a Cold War balance of power to a one-sided slaughter. Spider-Man may have never really belonged to us, but even the pretense that he did is gone, and as long as the market keeps growing but the number of companies serving it keeps shrinking, what you’re buying at your local isn’t a comic. It’s a bank statement, a bill for something that hasn’t been made yet but is already overdue.