I first became aware of Marc Bell's work in the mid-'90s, just as minicomics seemed to be booming in the medium's own small way. Marc published prolifically (and, unbeknownst to me at the time, already had two "real" comic books to his credit) in minis and in newspapers and magazines. As the minicomics scene began to die off in the early '00s he started appearing in anthologies (including my own) and then moved into galleries and books of his own. He's published four volumes of his work: an art book, The Stacks (Drawn & Quarterly); Shrimpy and Paul and Friends (Highwater Books), a collection of strips starring the titular characters; the monograph Hot Potatoe (Drawn & Quarterly); and most recently the comic strip collection Pure Pajamas (also Drawn & Quarterly). Additionally, he's edited books including Nog a Dod (Conundrum/PictureBox) and published scores of zines of his own. He currently lives in Guelph, Ontario with the artist Amy Lockhart.

It's been an intriguing journey, as he's developed a way to render his world across multiple platforms that communicates to viewers but remains completely his own language. His work zigzags back and forth between purely transparent, classic cartooning to much more interior image-making. In whatever mode you find him, however, when you're engaging with Marc's work you're playing by his visual rules. He took the lessons of imagists like Karl Wirsum and word-play collagists including Ray Johnson and managed to apply them to comics, which makes for layered reading/viewing experiences. When he segues into making stand-alone artworks, Marc wisely drops the narrative and manages, in drawing, painting, and collage, to create carefully defined spaces in which to explore private languages of line, color, and form, unencumbered by narrative or two-dimensionality.

I've published and been friends with Marc for a while now and with the release of Pure Pajamas it seemed like a good time to talk. We conducted this interview in September of this year at my apartment in Brooklyn. It was transcribed by Conrad Groth, Janice Lee, Ben Horak, and Kara Krewer. Marc and I edited it for length, clarity, and to make ourselves seem much more articulate than we really are.

DAN NADEL: What I was thinking this morning about SPX was this: A lot of stuff, it seems to me, in this current generation lacks a certain amount of imagination, but actually I think what I mean is it lacks a unique interior vision. So when we talk about Ron Regé, or you, or Amy Lockhart, there’s a particular aesthetic that cannot be duplicated, it’s unmistakable, and it seems to come from a pretty deep place. There’s no appropriation involved, there’s no trying to be something else, and there’s not a sort of friendly “Hey, come on and shake my hand” quality to it. What are you now, like 39?

MARC BELL: 39, yeah, I’m turning 40 in November. Lordy Lordy.

Oh shit, you are fucked. [Laughter.]

What are you, 35?

35 now. I do think when you were coming up, and Ron, John Porcellino, whatever all the stuff was, was pretty outsiderish. What do you think? [Laughter.]

No, it’s true, I mean this stuff has a definitely folky kind of quality, and people like Ron, it’s unique…I mean, what are you asking me?

I’m asking you what’s changed. What do you think has changed over the last 10 years?

Ok. The era of Archie Bunker’s chair is ending. Dads are nicer now, the kids are more friendly, there’s not as much, maybe, anger, like I don’t think Ron’s work is angry, necessarily, and I don’t know if mine’s really that angry, but there’s…

But it’s confused.

But it’s confused. Yeah, now people want something very clear, it seems. We were talking earlier and you used the word “pop-y”…I don’t know what point I wanted to make with this.

I don’t know. I’ve never thought of the Archie Bunker’s chair thing, that’s good.

Archie Bunker’s chair is floating out to sea. It is obsolete. Do you understand what I’m saying?

I do, I do, I think…

I do think it’s kind of a generational thing or a “sign o’ the times”.

We were the new generation not so long ago, Marc. [Laughter.]

It’s over.

It’s over?

Thurber’s the new generation.

Thurber’s our age.

I know. [Laughter.] It’s funny, when you first contacted me, I saw you as part of the younger generation. I suppose when you are younger it seems like someone a little younger than you is. Ok, but let’s try to think of...

Michael DeForge.

Michael DeForge, but then his stuff is really straightforward.

Very.

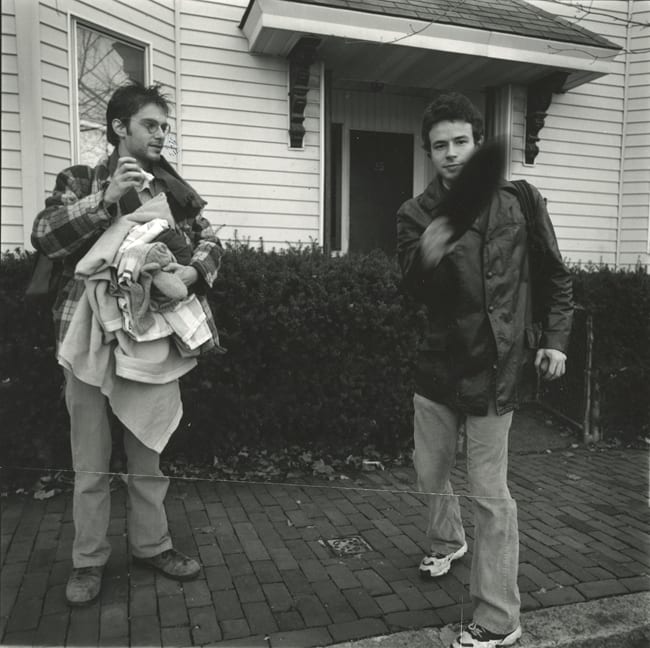

Very straightforward, pop-y. I gotcha now. I thought you were asking me who the new version of “us” is. DeForge’s stuff is certainly not as confused and crusty, and Archie-Bunker’s-chair-ishy as my stuff. I mean, when I was 19 or 20 or so I designed this gig poster, and someone was saying to me, “Oh man, looking at your drawings I thought you were like some 50-year-old underground freak or something.” It was something I did when I was 20, and he thought I was 50 years old. I just did a signing in Pittsburgh, and these guys came up to me, and they were laughing, and they were like, “Oh my God, we thought you would be like, wearing a duster, like an overcoat and shades and…”

That’s so funny, because part of the appeal of your work is that in some weird way, once you key into it, it’s very matter-of-fact.

Yeah.

It may be crusty, but there’s an order to it: Your arrangements are solid and the information is all accessible, more or less. It’s graphically precise work and it’s not like you're injecting a persona in there.

No, I don’t know exactly what that joke was, but I think they thought I would be more haggard or something. Because of all the drawings, artwork, and stuff. I think maybe they were surprised I still kept some kind of youthful-ish appearance. But anyway that’s beside the point. Yeah, because it’s true, my work isn’t really about a persona necessarily. I mean some of my autobiographical stuff is joking about that, I guess. But that stuff’s sort of long gone.

Yeah, it’s long gone. That was the ’90s. That was the heyday.

That was the mid-'90s, when we were the new thing.

Speaking of the ’90s, the first time I ever heard anything about you as a person was Ron Regé telling me, I think this was before you and I even corresponded, Ron Regé was telling me that you lived in a van outside his house.

No, no, no, I was visiting Ron with my friend Neil and my friend R. J. (this hilarious newfie pharmacist), and we drove down to Cambridge in a propane-powered van which Neil later sold to Elf Power.

Oh, really? The band.

Yeah, the band. And then the van traded hands and ended up with Olivia Tremor Control. Neil is buddies with those Elephant 6 guys, and the van ended up being passed around Georgia between those bands, because I think propane is really cheap in Georgia, right?

Right.

So a propane van is excellent for touring around there, I’m sure in certain states it’s really expensive. So anyway, we drove down from the east coast of Canada, we drove down to, well they were driving south, and I had never met Ron before, and we stopped in and visited Ron in Cambridge. At first we couldn’t get a hold of him or something, and it was really cold, and we were trying to sleep in the van, and I so cold I went and slept a little bit at the Kinko’s, until they threw me out of there. [Laughter] But we eventually met Ron, and hung out with him, which was great, because I had been corresponding with him. We had been sending mini-comics back and forth. And on that same trip, Ron was like, “Hey, Marc, you should come. I’m going to Providence, there are these crazy guys there that have this giant space, and they do shows and they make posters and it’s just nuts, you should check it out, you’d probably like it.” And I was like, “That sounds pretty interesting, but I’m going on this trip with these guys.” So, I didn’t get to go to Fort Thunder back in the day. But then I later I found out about all that stuff happening in Providence and met Ben Jones through the mail, and all that.

So how important was that community thing to you, coming up? Because you were exchanging minis with Ron, what starting in ’97, ’96?

Yeah, it was important to me, I was really taken by Ron’s stuff. Like you say, when you’re describing that old kind of cartooning that maybe isn’t as prevalent right now, or there’s not as much of it coming up now, he really embodied that. And then at the same, I was working with all these other Canadians, so it was just making a connection in the States. Ron was an American version of the stuff I responded to. It’s not just Ron; there were all sorts of other ones. But Ron was important, I think. And John Porcellino, who was really nice about promoting my stuff through his Spit and a Half distro.

Well, let’s go back to London. So, you were born in 1971 in London, Ontario.

Yeah.

And what did your parents do?

Well, my dad worked at Ford, and my mom worked at Woolco, which became Walmart. Walmart bought it out.

And how many brothers and sisters?

Twin sister and an older sister, a year older.

So what were your earliest visual memories?

Oh, I dunno, I can’t remember.

Really?

Yeah. I can’t, can you?

Yeah.

What were your first visual memories?

My first really vivid visual memories are like, oh wait, maybe I can’t remember either.

I don’t have a great memory. I talk to my friend Neil when I need some information about my past. He has a really good memory, he’ll remember exact dates that things happened on. But he probably wouldn’t remember my first visual memory. I used to have dreams of pretty detailed drawings.

When you were a little kid?

I’m pretty sure. I’m pretty sure, unless I’ve fabricated that. You know how sometimes people fabricate memories?

Sure.

But I’m almost positive I had dreams of detailed images or drawn images.

When did drawing become a real concern?

I think pretty quickly, I was always into it. I mean, people say, “Aww man, it must take you a long time,” And I go, “Well, yeah, but not really. When I get rolling I can really draw really fast. Just because I’ve done it so much. That’s what everyone always asks me, “How long did that take?” It’s just like, “I dunno,” it’s kinda second nature.

And did your parents respond at all?

Yeah, they were fairly positive, they just probably got worried when I was older, like, “What are you going to do now, what are you going to do with that?” But I was encouraged, I guess.

By your mom or your dad or both?

Well both I think, initially. It was something I just did, and I wasn’t stopped.

When did you actually start getting schooling in it?

Well, I guess Beal Art, which was a two-year course at a high school level. I finished a whole high school diploma or whatever, and then I went to Beal Art. So I actually ended up with 52 high school credits when I only needed 30. [Laughter] Before Beal Art I had an art teacher in high school who actually confiscated stuff I was doing. I was drawing on 8 ½ x 11 papers folded over – just drawing these really stupid comics. And they were in pencil. My best friend and I had these joke characters, the Galaxy Gang, where we’d try to draw beneath us. Like, we weren’t that technically accomplished, but we were trying to draw like little kids.

Even worse?

Yeah, worse. I think we were inspired by the art in those Roger Ramjet cartoons, how basic and immediate it all was. We were making these in elementary school so these ones that were taken from me were a later version that I was drawing by myself. In this case, the main character “Jimmy” had grown up a bit and was into hardcore punk and drugs and that kind of thing. So, I was drawing these comics, I don’t even know what the content was, but maybe they were somewhat objectionable, like adolescent, stupid humor. Anyway, my teacher saw what I was doing and he took some of them and didn’t give them back. Also, I drew a strip for the school paper once featuring Jimmy as this terrible, violent machine shop teacher who would injure his students. I was actually in the school’s machine shop class when I drew this and my teacher, Mr. Hendry, thought it was about him, that I was somehow making fun of him and I think I was called down to the office and given a talking to. The sad thing was that I really liked Mr. Hendry, he was a super nice guy and I was doing well in the class but I don’t think they understood my satire. Or lack of satire. I was so mortified by it all, I don’t think I could explain my way out of it.

Did Jimmy make any other appearances?

A friend of mine, Charles, bought one of these swish barrels, a barrel that had been used to make whiskey in it. You put water in it and turn it every few days and later you bottle it and there you have it, some sub-grade booze. We decided to call it “Jimmy Juice” and so I made a label for it with Jimmy lying drunk in the mud or something like that. We did some promotion, made a short commercial. We somehow managed to get the high school Vice Principal to endorse it on videotape, saying something like “Jimmy Juice, the stuff that girders are made of”. That was the official slogan.

Why didn’t you just go to Beal Art instead of high school?

That’s a good question. Maybe I was too scared to start going to school downtown, or maybe I didn’t know you could do that. But maybe it was better in a way because I was done with high school, and then Beal Art became this two-year art course. So I’m getting credits for it, but it’s almost like going to art school. And having finished that program, they let me into university in second year.

Ah, so you got out and into university.

Yeah, but they actually asked me to leave Beal.

Why?

They really wanted me to be an animator. I took the film/animation course in my second year but I didn’t want to do any animation. I had a video camera, and I was always videotaping stuff, and just goofing around with the video camera. I was constantly recording stuff off the television when I was a kid, recording movies, doing stuff like that. I made a very rudimentary documentary about Peter Thompson after I met him there at Beal. So anyway, I wanted to take film and maybe learn how to edit and stuff like that, and that’s why I took film/animation. But the teacher clearly saw I was interested in cartooning, and he was really pushing me to go to this school, Sheridan College, which is an animation school. And he would say stuff like, he’d say, “If you don’t do this, you’re just going to end up working at IGA and you’re going to be a failure…” [Laughs] Like that kind of stuff, you know what I mean?

So he was taking the ironic stab of pushing you into a lucrative career in animation, which is not lucrative at all. [Laughs]

Yeah, that’s right. Maybe back in that day it seemed like it would be, I dunno. But Sheridan was like a farm school for Disney, right? I think even Americans, some of them, would go out to Sheridan. It’s pretty well known. But anyway, they wanted to kick me out at one point.

Because you wouldn’t do animation?

I don’t think I saw myself as a rebellious student, but they saw me as someone who was really single-minded and knew what he wanted to do, and they didn’t see that I was taking anything they were offering, in a way.

That’s it.

And in a way I kind of take it as a compliment, in retrospect, but at the time, I was kind of hurt by it. I was like, “What? You want me to leave? What have I done wrong?” So I asked them if I could stay. And there was one other thing that was kind of funny. I was walking by the teacher’s lounge one day, and I noticed there was a Life in Hell cartoon and it was one where—I might not be explaining it exactly the way it was—but the general idea, I recall, was that there was a view of a classroom, and all the students were standing beside their desks, and then Binky is turned around, and he’s facing a corner and they labeled him “Marc Bell”. So they really saw me as going against the grain.

So what were you doing? I mean, what were you drawing? What was the work?

At Beal Art I was doing lithography, which wasn’t working out great because I would often mess up the stone. And I was taking that film/animation course, and again, the teacher really didn’t think that was working out, because he wanted me to do animation, so I actually switched to ceramics weirdly enough. I started making these really stupid ceramics sculptures. At one point I think the teacher came aside and said, “You know Marc, when you cast something in clay, it lasts for a long time, especially if you glaze it and stuff, this is going to last for a long time, so you should be aware of that.” [Laughs] You know what I mean?

So basically he’s saying, “Your stuff looks like shit, maybe you should think twice about it.”

[Laughs] Yeah, or like, “What do you think you’re doing?” I was making some of my cartoon characters in three dimensions. I had created lithographs of some of these characters also. And so I was making these creatures, they would have a clay body, and then it would have eight legs made out of doweling, with clay kneecaps. I didn’t really have a clear vision of what I wanted to do, but I was drawing comics, and I was a little all over the place, but that’s what school’s for, I guess, right?

Yeah.

I don’t feel like I really figured everything out till I was thirty, really, in reality, you know? Like technically. And then when I went to Mount Allison, I took printmaking, I was doing etching, and then…

Mount Allison, that’s Sackville?

That’s Sackville, yeah. I took printmaking, and I was drawing.

So, London though, seems like it is, or was, a pretty interesting place.

It was, it was.

In the ’60s and ’70s there was a pretty vibrant scene there.

Yes, in the ’60s and ’70s definitely. The whole Greg Curnoe/Murray Favro/Nihilist Spasm Band regional scene was going on and as an art student it was always sort of there in the background. In the ’80s it didn’t feel like much to me at the time growing up there but in retrospect it was actually pretty interesting and thriving in it’s own way. We had some interesting teachers at Beal, like Joseph Hubbard, who was doing really funny and interesting stuff and still is. London took a real hit in the late eighties and early ’90s and the downtown really went down the tubes like in a lot of mid-sized cities.

One of the big themes of your work is working with friends, and so in London you met Pete Thompson…

Yeah, and Jason.

Jason McLean. Is it fair to say that that was the core crew, initially?

Initially it started with myself and Peter and our friend Scott McIntyre working on collaborative drawings and Jason was making sculptures but he would have us over at his apartment and we’d listen to the Nihilist Spasm Band and Peter would read from The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy or something like that. And we formed the All Star Schnauzer Band. And then Jason went out west, and then I went out east, but we all still kind of kept the thread alive, one way or another. The thread actually became more involved later on. I guess the height of it would have been the late ’90s and early 2000s.

(Continued)