Countless comic-book fans, critics, and historians tell the same story about the moment when “everything changed” for the superhero:

Comics finally grew up in the mid-1980s with groundbreaking grim and gritty works like Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore’s Watchmen, two comics that, for the first time, portrayed complex and realistic superheroes.

I’m not convinced, though, that the emergence of psychotic superheroes ushered in an age of psychological realism. Though these graphic novels and their offspring deliver a darker vision of heroism and “the hero’s motivation,” they frequently rely on familiar moral dilemmas, stale genre conventions, and worn-out tropes of “superhero grandiosity”: Our metropolis is overrun by villains! The end of the multiverse is near! What great man will rise to save us? While the world of superhero fantasy may be grimmer and grittier than it was in the early ’80s, in many ways it hasn’t changed at all.

A recent Daniel Clowes faux-Batman cover offers a genuinely new version of an old superhero that I find more disturbing and enlightening than the genre’s revisionary classics. Clowes created the drawing for genius designer and mega-Batman fan Chip Kidd, who asked artists to draw the Dark Knight on a page with the Batman: Black ’n White logo:

Clowes’s image mocks the genre’s investment in escape fantasies: there’s no alluring hero, no fisticuffs for justice, no empowering melodrama in which readers can lose themselves. Instead, Clowes gives us a portrait of fear and humiliation that’s both funny and unsettling, just like real life:

1. “A Thrilling Home School Adventure!”

Traditional superhero stories exploit the hero’s emotional home life to lend tension and pathos to his superheroic activities. We care about Peter Parker’s Aunt May, for example, largely because her illness will affect Parker’s performance as Spider-Man. If he runs into The Vulture or Electro while on nightly patrol, he might be so freaked-out about his dying aunt that he’ll lose his spider-concentration when he needs it most.

Traditional superhero stories exploit the hero’s emotional home life to lend tension and pathos to his superheroic activities. We care about Peter Parker’s Aunt May, for example, largely because her illness will affect Parker’s performance as Spider-Man. If he runs into The Vulture or Electro while on nightly patrol, he might be so freaked-out about his dying aunt that he’ll lose his spider-concentration when he needs it most.

What makes Clowes’s cover comically unsettling is the way it locates the source of superhero narrative tension, not in violent spectacle (and the constant promise of impending violence), but in the claustrophobic dynamics of a family at home. Superhero comics tend to look outward, emphasizing heroes’ public performances on behalf of the “public good” (or so the heroes tell us). In reality, superheroes are flamboyantly costumed narcissists who fight evil in urban environments because they need to be seen — and loved by the masses. Clowes ignores the genre’s reliance on social theater and turns inward. His "hero," though a conventionally imposing authority figure, is really a domestic tyrant, an everyday supervillain. Clowes reminds us that stagey over-the-top fantasy battles pale in comparison to the emotional battles we fight in private, in our homes.

Heroes glam up when they leave home to engage the rabble, not when they’re doing homework— that would be too weird. If we were to imagine a Bat scene of education, we’d expect to see Bruce Wayne or the butler Alfred tutoring Dick Grayson (Robin’s alter-ego). But Clowes's image gives us something revisionary and revolting: a domestic vignette of a hero mean-spiritedly disciplining an adolescent orphan. It’s extra sick and funny because The Dark Knight and The Boy Wonder wear their S&M-y garb during Robin’s “lesson,” a lesson in domination and submission. Is Batman such a committed fetishist that he forces Dick to costume-up just to study economics?

(Similar moments of domesticity pop up throughout the classic 1966 Batman TV series/movie, an important inspiration for Clowes’s faux-cover):

As a young comic-book reader, Clowes preferred scenes of the hero’s daily life to those in which he fights supervillains. His Batman cover taps into this kind of “relatability.” Robin, no longer the sidekick, is now the victim, a vulnerable teen about to expire from fear, not because he’s battling a sadistic Joker, but because he’s bullied by a sadistic Batman.

I can’t relate to super-champions like Green Lantern or Adam Strange when they’re flying in space and trouncing trans-dimensional scoundrels, but I can feel Robin’s fear and embarrassment, just as teen me felt Peter Parker’s and Richard Rider’s home and school troubles (Rider is Nova’s teen alter ego). Who hasn’t experienced humiliation courtesy of an overbearing authority figure?

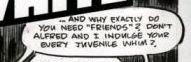

2. “And why exactly do you need ‘friends’? Don’t Alfred and I indulge your every juvenile whim?”

Batman’s home life, like the superhero universe it reflects, is an androcentric space, a boy’s club. It’s also a sealed-off nuclear family with two adults and a child (Batman, Alfred, and Robin), a homosocial environment of male discipline. Since a traditional heterosexual relationship will only inhibit a male hero’s ability to risk his life for “the public good,” he must shun the ladies (or so he tells us).

Just before the cover scene takes place, Robin must have asked Batman if he could hang out with kids his own age, maybe even some girls. But Batman, domineering, paranoid, and super-insecure, doesn’t like this, responding like an all-too-familiar real-life type: the jealous, controlling boyfriend, who says to his girlfriend, “Why do you need friends when you have me? Aren’t I enough for you? Don’t I indulge your every whim?”

We might think a dictatorial male like The Batman would insist that his charge call him “Father,” a term that conveys patriarchal and authoritarian formality. But, always the creep, Batman employs — and perverts — the familial intimacy of “Daddy.” His preference for “Daddy Bruce” highlights the superhero comic’s fetishistic blend of dominance and desire within the context of costumed play. Who’s your Daddy, Robin? Say my name, Robin. Ick.

While superhero comics often take themselves very seriously, Clowes alerts us to how comically twisted the genre can be. His cover functions like a one-panel exposé in which he out-revises the revisionists: “Unmasked: The Sick Home-Life of America’s So-Called Superheroes!” When not out saving the world, caped crusaders lurk at home, corrupting America’s children.

3. “Color is strictly for fruitcakes and libtards!”

Does Bruce Wayne recognize the repressed eroticism animating the scene beneath his cartoony talking head? He looks directly at readers to tell us — and perhaps reassure himself — that he ain’t no “fruitcake” (not the best language for a children’s role model). Clowes reminds us that the classic superhero narrative depends upon contradictory impulses: an overt denial of same-sex attraction and a veiled appeal to homoerotic desire. Perhaps knowing the cliché that “superheroes are gay,” Bruce preemptively insists he’s not, despite the Bat Cave lifestyle he has engineered.

He also lets loose “libtard,” a derogatory term that defines liberalism as a form of mental and social retardation. Classic superhero morality has no room for communally-minded folks believe in “the social good” and see “grey areas.” Morality is Black and White! Maybe the title Batman: Black ’n White is kind of redundant.

4. Austrian Economic Principles, The Bell Curve, and Eugenics.

While undergoing his Batman-approved curriculum, Robin doesn’t learn a foreign language, work on trigonometry, or study American Civics. Isolated from the debased public school masses (with whom he might enjoy a social life), he reads texts that espouse the ideology of the archetypal American superhero. These books will teach Robin that he and Batman are worthy exemplars of The Great (White) American Hero because Nature has ordained their supremacy. It’s social evolution, old chum!

While undergoing his Batman-approved curriculum, Robin doesn’t learn a foreign language, work on trigonometry, or study American Civics. Isolated from the debased public school masses (with whom he might enjoy a social life), he reads texts that espouse the ideology of the archetypal American superhero. These books will teach Robin that he and Batman are worthy exemplars of The Great (White) American Hero because Nature has ordained their supremacy. It’s social evolution, old chum!

Austrian Economic Principles.

Perfect for today's super-man, the Austrian school of economics relies on “methodological individualism.” Sounding like a bardic Übermensch, an advocate of the school’s principles proclaims that “Only individuals choose. Man, with his purposes and plans, is the beginning of all economic analysis. . . . collective entities do not choose.” The sexist conflating of “Man” and “individual” seamlessly aligns with Batman’s and the superhero genre’s masculinist anti-social worldview (the Bat Cave is the original Man Cave). Bruce Wayne is super rich because his father made rational choices that logically resulted in fiscal reward. They deserve all they have, unlike the poor, who, you know, choose to be poor. No surprise that libertarians like Ron Paul, who reject government action on behalf of disadvantaged “collective entities” (i.e., poor people) worship this school. “We are all Austrians now,” he once declared.

The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in the United States.

This 1994 book by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray will show Robin that he’s a member of the “cognitive elite,” those who have succeed by virtue of superior intelligence. The Bell Curve’s widely discredited “science” has been used to justify narratives of white achievement and minority failure. As Bruce Wayne’s adopted son, he and those like him represent the group in which intelligence has naturally “clustered”: upper-class white males.

Eugenics.

Many sociologists have suggested that The Bell Curve is simply a dressed-up version of outmoded racist philosophies like eugenics. This pseudoscience advocates human evolution through interbreeding “superior persons” (the white elite), and endorses sterilizing or eliminating “inferiors” such as criminals, the poor, black people, etc. Like classical superheroism, eugenics sees the world as a battle between humanity’s higher and lower orders. (What weird pseudo-scientific experiment is Batman having Robin perform with the test tubes, something about the supremacy of Aryan blood perhaps?) Though eugenics has its roots in Victorian-era science and philosophy, it took hold early in the twentieth century, setting an ideological stage for the rise of paperback pulp heroes and comic-book superheroes in 1930s America. (Similarly, some of the Austrian school’s most important books, such as Ludwig von Mises’s The Theory of Money and Credit, appeared early in this century.)

With Robin’s carefully selected reading material, Clowes reveals the economic, social, and scientific basis of the traditional superhero’s classist, racist, and sexist ideology. When fully initiated, Robin will view his foes as degenerates from what “the select few” have long reviled as “the dangerous classes.” Superheroes are our cognitive and physical super-elite, and, as current box-office receipts more than prove, they are our Phantasy Overlords.

5. “WE CAN BE HEROES”

In perhaps the cover’s most inspired moment, Clowes, a master of word play and puns, deconstructs the banner atop the page Kidd asked artists to use (it features DC superheroes in silhouette). With two erasures, Clowes transforms “We can be heroes” into “We can be eros,” altering the surface text to divulge its subtext, its real meaning. In superhero comics, Heroes hides Eros — the appeal of heroism and morality covers up the appeal of eroticism. Caped crusaders act out, not to make the world safe, but to get some action. The same is true for readers. They don't want a chaste comic-book morality play — they want a sexual power fantasy.

Long before Watchmen, superhero comics told us they were sexually weird, but we didn't listen. We chose to believe they were heroic fables for children. In 1954, Fredric Wertham warned us. He famously said that comics hide dirty “pictures within pictures for [those] who know how to look.” Ever the Werthamite, Clowes shows us there are dirty words within words, too.

6. “DCLOWES COMICS”

We sometimes forget that American superheroism began as, and still largely is, a corporate-controlled phenomenon. It’s not based on timeless appeals to Gods or Goodness that naturally arise from “the folk” or “the human condition” (“Superman represents the best in all of us,” one self-help-y comic-book writer recently declared). Corporations create spandex-clad “role models” so they can hustle merch adorned with heroic characters and their logos: toys, t-shirts, mugs, tooth brushes, and maybe a few comic books. (If they had sold Silver Surfer cigarettes when I was an alienated teen, I’d likely have lung cancer today.)

Clowes hasn’t forgotten who owns America’s heroes. In the ultimate act of comics revisionism and corporate takeover, he plays graffiti artist, inking his tag — DClowes — over DC’s, usurping the ™ of the company that controls The Batman and his ilk. Clowes’s subversion of the logo recalls his transformation of the banner’s inspirational phrase “We can be heroes” into “We can be eros.” Always alert for hidden messages, Clowes peers deeply into the page he was given, allowing it to reveal opportunities for meaningful defacement and disclose messages that the higher-ups want suppressed. Clowes’s short comic may be as subversive — and revisionary — as a superhero comic can get.

*

Superhero myth-maker Stan Lee once told us that “with great power comes great responsibility.” But the truth is less flattering, less uplifting. In real life, a hero’s power would come with great temptation for abuse, even perversion. If we knew how nasty a real Batman-esque “superhero” might be to a sensitive youngster like Robin, if we thought about how warped theses characters’ home-life might be, would we really want America’s children (or adults) wearing t-shirts and pajamas plastered with the smiling faces of sadistic superbullies?

____________________________________________________________

Ken Parille is editor of The Daniel Clowes Reader: A Critical Edition of Ghost World and Other Stories. He teaches at East Carolina University and his writing has appeared in The Best American Comics Criticism, The Believer, Nathaniel Hawthorne Review, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, Comic Art, Boston Review, and elsewhere.