BOUND & GAGGED

VALENTI: So let’s talk Bound & Gagged. You didn’t edit — you “curated” — these riffs on the gag cartoon. What was the genesis of that project?

NEELY: Secret Headquarters comic shop asked me to curate an art show for their store, and they originally suggested a themed show of Dennis The Menace. And I was like, “That sounds boring and rigid to me.”

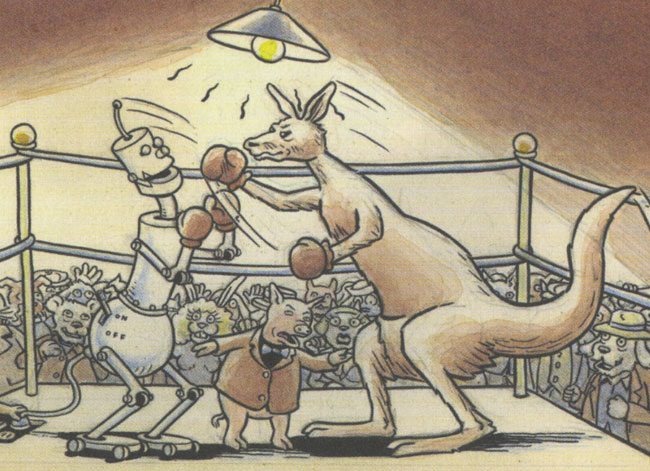

But I’ve always liked the idea of comics as art and art as comics, art-comics in a fine art sense or whatever, visual art in both those realms. I love a lot of cartoonists and I love their artwork. But cartoonists aren’t necessarily painters. Asking a bunch of cartoonists to do a painting show isn’t always the best result. I curated a few shows like that earlier in the ’00s. So I thought, just asking everybody to do just one-panel comics distills what I like about painting, telling a story in a single image. You get aspects of painting, but it’s still comics. So I came up with that idea of just asking people to just do their own interpretations of the one-panel gag strip. Which just seemed like no-brainer to me, but it was funny how many people came back to me like, “One-panel comic strips are really hard.” And I didn’t think of it that way, ’cause I almost always start by thinking in single images. And then those single images get linked and then it turns into a story. But I guess it’s the opposite for some cartoonists. To distill it into one image: It’s really difficult. So it was an interesting process to talk to the other artists and deal with that.

I didn’t call myself an editor on it because, I didn’t tell anybody what to do, except make it one panel. I didn’t give them any size limits or restrictions or formats or anything. I just was like, “Approach it any way you want,” ’cause I think that’s how you get the best work out of people. And it’s rare in comics, I think, that artists are given that much freedom: either from dealing with editors or dealing fan expectations or whatever. I think there’s a lot of pressure on cartoonists to fulfill some expectations, and I didn’t want to do that to anybody. So I didn’t feel like I was editing, but there was a lot of editing process to put the book together and a proper flow to everything. I called it curating because it was more like putting together a show of artists I trusted to give me good work.

I really like this book. I can’t sell it to save my life. No stores want to keep it in stock or anything. Oddly at TCAF I sold 20 copies in an hour, or two hours, and that’s never happened before. I don’t know if Canadians have a weirder sensibility about comics, but I really love this book. I love all the artists in it. I’m amazed, like I was saying about my tour, the fact that I can now contact somebody like Anders Nilsen or Josh Simmons, and they would actually do something for a stupid little book I wanted to put together, that’s really cool to me. Or Kim Deitch or Marc Bell, that’s really a personal achievement to me that I can not only call some of those people my peers, but actually have them do something for this stupid little book I wanted to put together. My [laughs] … what do you call it … my “mission statement” for this book in a way was, my dream would be, 50 years from now I would find this in a quarter bin in a dusty old book shelf next to those old Peanuts paperbacks — because I love looking through those Peanuts paperbacks in old book stores — and the idea that some kid might find this in a quarter bin.

That’s how I discovered indy comics. The first indy comic I ever found was Renée French’s Grit Bath in a quarter bin in a comic shop in Tulsa, and it changed my life. Not that I expect this to change anyone’s life but, you never know. Some kid might find it somewhere for super cheap and might learn something or get some ideas, and that’s the whole idea behind it: and to promote my friends that I like. But so far it’s a failure [laughs].

VALENTI: I was wondering if you were able to pay people.

NEELY: No, no I wanted to but I wasn’t able to. I just paid them in copies of the book that they could sell. I’ve still got plenty of them, so anybody that wants more, I give them to them. So, I wasn’t able to pay them. There was also an art show at Secret Headquarters in conjunction with this, and a lot of the people in it sold some work, so I think everybody was happy in the long run.

VALENTI: I never came in through the direct market at all. I read everything in the library … but to me it’s all the same, it was all right there. I was reading Trondheim and Love and Rockets and Charles Burns and Ellen Forney and Cathy all at the same time.

People talk about comics literacy and I’m like, everybody reads comics all the time. My mom reads comics. She just doesn’t think she’s doing it; she doesn’t process it as that. People don’t read them the way we want them to, but people do it all the time. It’s just a question of taking everyone on their own level and how they deal with it, instead of going, “They must love Maus because Maus is really…” and I’m like, “No, not everybody’s going to read Maus, and not everybody’s going to love it.”

NEELY: Yeah, that’s something that’s been really important for me to learn over the years. When you’re younger, you have this idea of what your career will be and what your goals are that are based on things you’ve seen. Like when I was first starting out, I really looked up to Jordan Crane and Sammy Harkham, and when The Blot came out I was like, I’m going to finally be accepted into that realm of indy comics, but that didn’t happen.

Then I found this other audience that I didn’t know existed, and it’s a weirder, more spread-out audience that’s a mixture of metalheads, because of my Melvins comic, and indy comics people and art-comics nerds and people that like old comics strips. It’s this weird mishmash of things that I could have never … if I had set out to find an audience, I would have never thought of that, or figured out how to find it, but it happened organically and naturally and it’s much more rewarding that way. I’ll sometimes talk to younger cartoonists, and they have that, “I gotta to do this and it’s gotta be done this way.” But it’s just as valuable and to try and expel those preconceived of audience from your brain, and to just let an audience happen naturally, it’ll surprise you if you open yourself up to it. This friend of mine in L.A. was trying to make a documentary about comics, and it’s all about promoting comics and trying to get more people to read comics, and I was talking to him about it, and his whole idea was just all about trying to get Average Joe to start going to the comic shop on Wednesday and buy comics, because he’s like, “Because not enough people read comics.”

And I’m like, “Everybody I know reads comics in some way.”

“There should be literate hipsters and people in bands and they should be interested in comics because they’re interested in art.”

“They are.” All my friends that are in bands have read some comics. They’re not going to read everything, they don’t go to the comic shop every Wednesday, but they’ve all read something and they all like something. And my friends that are librarians, who love Dan Clowes and Chris Ware, they’re not necessarily going to like some of the other weirder arty stuff that I like. There’s so many different factions in the comics world, and I really like that there’s so many different small communities and it all adds up to this bigger mess of a community. I think it’s important not to focus on any specific one.

VALENTI: I work hard to maintain non-comics friendships.

NEELY: Yeah, I’m the same way. For years I kept thinking, I want to move to Portland, because it seems like a cartoonist paradise, but over the years, the more I would travel up there, I started realizing, everybody lives in this 24-hour, 365-days-a-year comic convention, and there’s so much weird drama going on. I’m really glad when I go back to L.A.

I really only have one other cartoonist friend that I see regularly, Levon Jihanian, and most of my close friends in L.A. are computer tech guys or animators or musicians and writers and people that are doing interesting things, but it’s different, and I don’t have to spend all my time thinking about comics. Again, maybe it’s part of growing up in Paris, TX — it’s still my own thing, but people are interested in it. Yeah, I like that.

VALENTI: I love to watch what my non-comics friends, when they come over to my house, what they pick up. I’ve got pretty diverse stuff, and I love to see what they’re drawn to, and it’s so fun. I had a friend who loved Moomin, that’s what she went for; somebody came in, and she was drawn to Wonderland, by Sonny Liew. I love to see what they visually respond to … mostly it’s women, actually. I have a lot of guy friends, but women are drawn to certain things, and I love to see that.

NEELY: Women are often more drawn to something different, too, it seems. In my experience, I think I’ve found I have more female fans than male fans, because men tend to have more specific … they’re a little less adventurous in their tastes sometimes, I think. Not to stereotype, but occasionally it seems that way.

I was hanging out with my friend Matt this weekend, and he works at this big design firm, and a lot of them are art-minded but more designer-tech people, and I met one of his friends yesterday. We went to a barbeque at his house, and he went to Art Center, and he was interested in comics and stuff, and Matt was like, “Oh, Tom did a book,” and he was telling him about it, and then he showed him a copy and I looked at his shelf and he had, you know, Watchmen and Arkham Asylum on his bookshelves, so he does read comics, but it’s still mainstream stuff, and he looked at mine and was like, “Oh, that’s … weird … interesting.” [laughs].

That gets frustrating sometimes too, especially when I’ll find out about a friend of mine who’s in an underground punk band or something that are at an obscure level in the music scene, but they’re taste in comics is no more obscure than Vertigo and I’m like, “Really? You should be reading Jose Gabriel Angeles’ grindcore comics.” It seems like if you’re in one underground aspect of the world, you should be more interested in other things in that level, and so I always get disappointed when people who otherwise have good taste in one form of art have not penetrated that in comics and their comics taste is rather pedestrian. But then you give them Love and Rockets or something like that it starts taking them down that well [laughs].

That was also part of the goal of this book too. I mean, when Secret Headquarters asked me to do that show, they were like, “We gotta get people like Jaime Hernandez and Dan Clowes,” and I was like, “I don’t want to do that, everybody’s seen what they’ll do.” I want to get people that nobody’s seen before, because Secret Headquarters has a very specific clientele of comics-literate hipsters, but they’re very limited in their scope as a far as underground stuff goes, and I want to show them a bunch of stuff they would never normally look at. It failed in that sense, but that’s fine [laughs]. At least I achieved my goal of exposing people to something briefly.

PUBLISHING

VALENTI: Could you break down self-publishing. Now you have I Will Destroy You, so that’s more than just a Xerox and zines, and I’m always curious to know how people do things, so if you just want to break that down… you draw your comic, and you find a printer, and then you pay for it, and then you can go to shows, and you have a website. I’m just interested in all the steps.

NEELY: I feel like I’m still learning a lot as I go along, but like I said, I started off just Xeroxing minicomics and giving them away, and then did that for years and submitted a couple to anthologies. And they would mostly get rejected, and so it was just like, well, I’ll just keep doing it. So then once I did The Blot, well, I did a mini of the first chapter, and I was submitting that again to publishers and everything, but at that time I was working with Global Hobo and Sparkplug a bit, and Top Shelf approached me and wanted to do The Blot. The more I talked to them, the more I realized I didn’t want to work with them, and wanted to just do it myself, so then I spent the next year while drawing The Blot researching and learning how to do a professional printing job and finding all of that out. And I keep refining the process and changing things and whatnot, like recently in the last couple years I finally found a printer in the L.A. area so I could print locally, because that’s important to me.

But yeah, the whole process, it’s a cliché, but I just talk about putting on different hats. First I’m the artist, and I’m like the cave-dwelling artist who doesn’t want to talk to anybody, and just …“stay away from me while I create this thing!” And then, once it’s finished, I start having to slowly push myself out of the cave, and that’s the PR or publisher side. I put on the publisher hat and start pushing the artist out of the cave. And then the production, I don’t really enjoy the production that much; I enjoy the production, but drawing is always my favorite part of it. But then, I’m starting to like the idea of dealing with papers, and going to do press checks at the printer and stuff. It’s becoming more fun and more of a part of what I do, so I really enjoy it, especially having a local printer. I really like being able to go down there and see it happening and look at everything coming off the press and make sure everything looks right. And it’s always interesting, the reactions to my work I get from the guys that are normally printing car catalogs, and then they see this stuff and they’re like, “Whoa! This is weird! What’s wrong with you?” [Valenti laughs].

The thing I’ve been trying to work on getting better at is the PR stuff and trying to get it out there a little more. I don’t deal with Diamond. I chose not to deal with them when The Blot came out; they approached me and I just don’t want to deal with them at all. I’d rather use smaller distributors, but I’m trying to still build that and get a little bit further each time. And trying to get better at PR stuff and this tour is a part of that, just trying to figure out things and how to promote in a different way. But now it’s evolving a little more; I’m starting to think about distro and publishing some of my friends as well, maybe expand I Will Destroy You, slightly. I don’t want to become a big company or anything, but you know, if there’s a friend of mine that I think is talented and I could help get their work out there more, I think I’d like to do that, so I’m starting to think about that stuff.

VALENTI: You spoke about being married to a journalist. Does she provide any feedback on your work?

NEELY: She’s always the first person to read my completed story. And she helps me write all the press releases and stuff that I’m no good at. But I’m kinda private about my process, even with her, when I’m working on something. I’ll show her what I’m working on and she’ll make little comments, but she doesn’t really provide a lot of feedback unless I ask her specific questions. I value her opinion, and she often gives good feedback about whether something works or doesn’t, but we have very different processes for how we approach our creative work. I think we have an ideal situation where we both understand having a creative pursuit, and all the ups and downs of that, but our creative pursuits are completely different, so there is never any weird overlap. It’s nice to have someone creative in the house, but who does something different. If we were both cartoonists, I think it could be disastrous. She is probably the best judge of my work, though. She knows me better than anyone else, so I know that if she doesn’t “get” something, nobody will.

VALENTI: A lot of indy cartoonists are doing these tours, especially now that it’s fall. What role do these tours play?

NEELY: I don’t know. This is my first one [laughs]. So far it hasn’t been the most lucrative venture at all, so I’m probably barely breaking even so far, but I guess spiritually, and I use that word in a non-denominational way [laughs], I feel like it’s been really good for my soul, especially after some recent events. It’s really good to just be out on the road and feel like I’m an artist and cartoonist full time. So whether it’s successful monetarily or not, it doesn’t really matter at this point, I’m just having a good time. And when I was scheduling the tour I was just thinking, how weird is this? Ten years ago I couldn’t get anybody to take my comics, and now I’ve got seven stores that want me to come do a signing and friends in every city that want to come hang out and everything, and that’s amazing. I never expected that, so I’m loving it from that standpoint.

We’ll see how it ends up being. I think having A.P.E. at the end of the tour will probably help the money drain, but it’s been really good so far. I haven’t really talked to other cartoonists about their tours, except John Porcellino. I talked to him about it, and I think he has a similar attitude: that it’s not necessarily the biggest money-making venture, but we both come from a DIY-punk rock mindset, so I think it just taps into that. I’ve always been friends with bands and stuff, so it’s fun to feel like I’m doing something similar. We’ll see if it’s worthwhile monetarily, which it probably won’t be, but what is in comics? So we do it because we love it.

TECHNIQUE

VALENTI: What are your techniques and tools?

NEELY: My techniques change all the time because I’m always trying new things. My pencils are always very rough because I prefer to put most of the work into the inks and paint and allow the art evolve through the drawing process. I like to allow chance and mistakes to happen and I never use Wite-Out — I prefer the original art to be clean and presentable like a painting. But lately I’ve been more interested in revealing a bit of the process in the final art, so I avoided doing any cleanup or computer manipulation to any of the art in The Wolf. So, some pages have visible pencils, tea stains from when I spill on my drawing table, and various other bits of intentional sloppiness that I really enjoy seeing in the final book. I work rather large too, because it helps with the wrist problems I’ve had from computer work. The originals for The Blot are all 18 inches by 24 inches.

My tools vary, but I mostly draw with either an Isabey series 6228 #3 watercolor brush or a Winsor Newton series 7 #3 watercolor brush. I’ve tried for years to find a synthetic brush that will work for me, because I’m vegan, but nothing really compares to those brushes. I occasionally use a nib or technical pen, but I always go back to brushes because I have so much more control with them. I prefer Dr. PH Martin’s Black Star Matte India ink because it dries fast and solid. I always draw on watercolor paper that has a good rough tooth because I like the line variations and that it’s a bit of a struggle to get a perfect line. I’ve spent most of the last 6 years only using watercolors for my paintings and comics, but lately I’ve been enjoying oils more — the cover of The Wolf was the first oil painting I’ve done since art school and I really loved doing it. Maybe I’ll do more of that.

VALENTI: What is your process?

NEELY: It changes with every project. The Blot was more of a standard approach of writing story outlines and thumbnailing in my sketchbook, then penciling a full version of the book in my sketchbook, then full-size rough pencils of the entire book on newsprint paper, editing the story from there, then transferring those pencils to watercolor paper and doing the inks and color. That whole process was kinda streamlined and only took me a year to complete the whole thing. On the other hand, The Wolf was completely disjointed and always in flux. I was working on different parts of the book simultaneously. I generated about 80 pages of extra art that didn’t make it into the book. Some drawings would be cut out, only to be added back into the story two years later. It was a very disjointed process that took over four years to complete. But I think that’s the way this book had to happen.

I think for my next graphic novel, I may need to find a process that’s somewhere in between these two approaches. I’m now working on another long series of one-panel comic/paintings that I intend to turn into a book at some point, and it’s a completely different process again. I guess I get bored if I’m too regimented.

SPARKPLUG

VALENTI: I did want to talk to you about Sparkplug. How did you get to be associated with those guys?

NEELY: Just through friends. In 2001 I met Dylan [Williams], and I had met Jesse Reklaw the year before, and then I was hanging out with him again that year at San Diego Comic-Con. He and Dylan were sharing a table that year in the small press section, and so he introduced us, and I was doing the One Fine Day comics at that time, so Dylan and I just started talking about old comics and ’30s comics, and I think I specifically remember us talking a lot about characters with the three-fingered white gloves, and then somewhere in there, Jesse interrupted us and said, “You guys are the only people I know that are into heavy metal, you should be talking about that, because I hate that stuff.” And so then we bonded over that. We just became really good friends over the years, e-mailing and talking over the phone, and I’d send him my comics, and we’d trade stuff, and we just kept up. And I started working with Jesse’s Global Hobo for a few years, because pretty much immediately, once I found the indy-comics world, I liked the idea of community and working with other artists, and so it was always more fun to go work with Global Hobo than to have my own table and to just have fun with a bunch of other people, because we’re all doing similar things. And I know that sounds “Team Comics” or whatever. Do people even talk about Team Comics anymore?

VALENTI: Well, collectives …

NEELY: So I was working with them, but then I think around 2005, it was only two or three years that Jesse was doing Global Hobo before he wanted to move on, and I even thought about trying to take it over at some point, but I wasn’t ready for that.

So then once I was working on The Blot, I just started going and helping out Sparkplug instead, and he would just give me a small section of the table for my comics if I helped run the table, and we just got a lot closer and started doing all of our shows together. And then once my stuff was getting better then we’d buy our tables together, and Dylan became pretty much the best friend I’ve ever had, so I might get choked up a little. From the beginning he’s always been the biggest cheerleader of my work, so I’d been working with him for a while. We just started doing every show together, just because we liked hanging out together and everything.

VALENTI: You’ve been helping and stepping in, taking over some of the tables that were already bought and…

NEELY: Emly Nilsson and Virginia Paine have asked me to be a partner in keeping Sparkplug Books alive. After a lot of generous support, both emotionally and financially, from many of our friends in the community, it looks like we’re in good shape for the immediate future. We plan to go to several shows next year. And we're on a path to be publishing new work in 2012.

VALENTI: It was such a specific thing. I have this joke and I tell everybody it, you’ve heard it a million times, but I would go to Comic-Con and say, “OK, I’m going to give Alvin [Buenaventura] 60 bucks, I’m going to give Dylan 60 bucks, and I can’t carry away more than this.” And every show I go, these are the places I’m going to find something. I just knew it would have my ethos. I really love buying comics directly from an artist. The curatorial sense was, maybe I don’t love everything here, but I’ll find something, and I’m willing to spend five dollars even if I don’t like it. And whatever, the artist got the five bucks. So there’s just this huge hole now, it’s just a hole in comics, and I don’t think anything is going to be able to …

NEELY: Yeah, I don’t think there’s anything that could replace it, but I think there’s enough of us that, like me, learned so much from Dylan and want to carry on that spirit in some way. I had dinner with Zack Soto Friday on my way up here, stopped in Portland and he was talking about how he and his wife want to turn his Study Group 12 anthology into more of a small press, and he’s thinking about publishing some other people. We were just talking about how that’s what we want to do to carry on the legacy in our own way, which I think is the best way to carry on Dylan’s legacy — to find your own way to do it, because that’s what he did. He didn’t copy anybody; he carved his own path, and he wouldn’t want me to just do exactly what he did. But we talked about publishing and everything constantly. We always had a lot of similar ideas and a lot of different ideas, and that’s one of the brilliant things about him; he had such a specific vision for what he wanted to do, but everybody else’s vision was worthy of supporting too.

VALENTI: I admire him.

NEELY: There is a hole, but I think that hole will be filled in a more dispersed way. It’s just less congealed now, but everything trickles down and spreads out, and hopefully for the better.