Pablo Picasso, describing the creative act of painting, once reflected that “It’s not an aesthetic process; it’s a form of magic that interposes itself between us and the hostile universe, a means of seizing power by imposing a form on our terrors as well as our desires.” Rarely in comics is this sense of creative “magic” so visibly evident on the page as it is in the work of Theo Ellsworth.

Pablo Picasso, describing the creative act of painting, once reflected that “It’s not an aesthetic process; it’s a form of magic that interposes itself between us and the hostile universe, a means of seizing power by imposing a form on our terrors as well as our desires.” Rarely in comics is this sense of creative “magic” so visibly evident on the page as it is in the work of Theo Ellsworth.

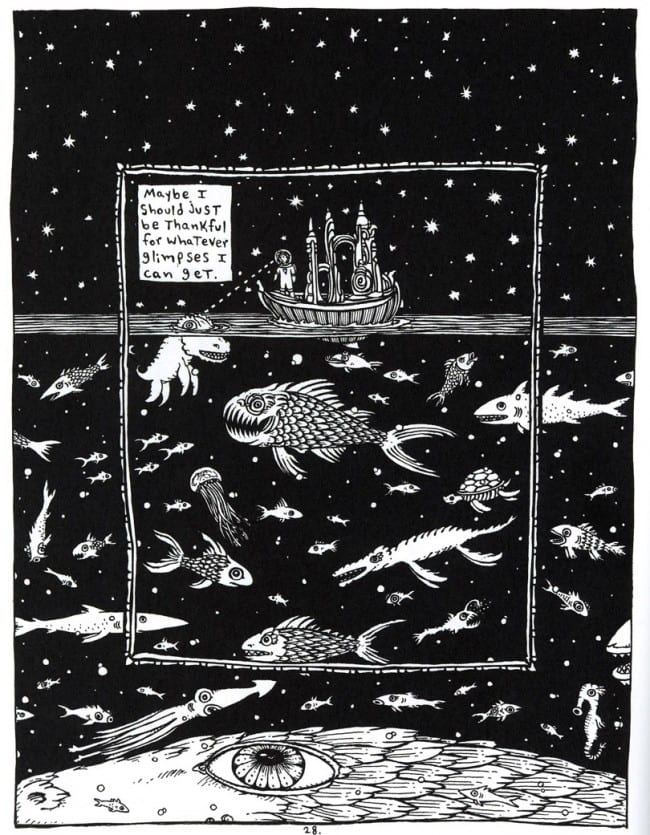

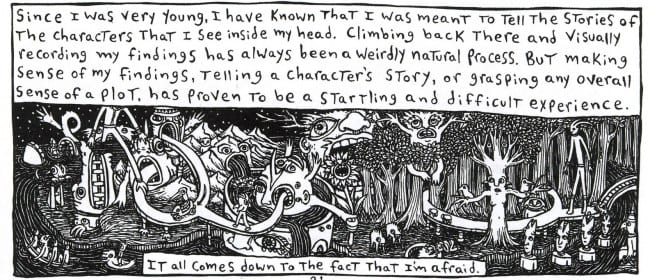

Capacity, Ellsworth’s debut graphic novel, was first self-published as a series of mini-comics before being collected, to great acclaim, in 2008 by Secret Acres. Part autobiography, part dream, part art therapy, it was one of the most blatantly psychological explorations of memory and identity ever captured in sequential panels. Its mythical stories of exotic creatures with extravagant headgear and benevolent monsters who speak symbol-based languages, were ostensibly a series of visual explorations of Ellsworth’s imagination (which the artist described as his “psychological thoughtplane”).

His artwork, which combines Ellsworth’s visions with meticulously textured drawn collages, seems at times as if it was poured onto the page like molten thoughts (Secret Acres’ marketing contributed to this perception by describing Capacity as “a mind turned inside out” while Ellsworth re-named his website the “Thought Cloud Factory”). Yet underneath its stunning compositions, Capacity offered readers a glimpse into the chaotic frontier of the artist’s psyche, and revealed that, at heart, Ellsworth is a philosopher poet masquerading as a cartoonist.

With his second graphic novel, The Understanding Monster, the first part of a planned trilogy, Ellsworth turned toward more traditional narrative to tell a character-driven epic. Weeks before its launch at SPX 2012, I was excited to speak with the artist about his sophomore effort, as well as delve into his background and influences. When we connected by phone in late August, Ellsworth was in the middle of a major transition in his life, moving his family, including his nine-month-old son, Griffin, from Portland, Oregon back to his hometown of Missoula, Montana.

Marc Sobel

October 9, 2012

CHILDHOOD

MARC SOBEL: Since your work is so rooted in memory and imagination, I wanted to start by asking you to describe some of your earliest memories.

THEO ELLSWORTH: Well, the first one that pops into mind is…I have this really bizarre memory of waking up in the middle of the night and walking to the foot of the stairs that led up to my parents’ room – I must have been like three or four – and seeing my dad’s head floating on the stairs, like as a hologram, and he was talking to me. It must have been a dream, but that’s one of my most vivid childhood memories.

SOBEL: Do you remember what he said?

ELLSWORTH: No. I just remember him saying ‘hello’ to me and smiling and then the memory stops there. But years later I told my brother about that memory and he got really serious and told me that he had that exact same memory.

SOBEL: Wow.

ELLSWORTH: It must have been one of those strange brother mysteries.

Another really vivid childhood memory I have is of falling into a koi pond at a Japanese garden in Los Angeles. My family lived in LA until I was six, and then we moved to Missoula, Montana. I remember watching the koi fish in the pond and wanting to reach out and touch them and then I just fell head first into the water. I remember sinking down to the bottom and sitting there for a moment, and having this really surreal, serene feeling about being at the bottom of a pond. I also remember looking up and seeing my dad’s face staring down at me, and then swimming back up.

SOBEL: How old were you?

ELLSWORTH: I must have been three or four. Then I remember the park attendant suddenly riding up in one of those little golf cart things and driving us back to our car, and stinking like a fish pond for the entire ride home. <laughs>

SOBEL: Were you born in Los Angeles?

ELLSWORTH: Yeah.

SOBEL: Why did your family move to Montana?

ELLSWORTH: This is going to sound like I have this weird, mystical family or something, but my dad actually had a dream that we needed to move to Missoula, and he decided to listen to that. But at the time my dad was a parole officer in LA, so he had a pretty intense job and I think it started feeling kind of claustrophobic and he just got tired of being in danger on a regular basis. I think it just hit home after a while and he wanted to move to a smaller place to raise his family. So we moved here and he ended up working with the elderly.

SOBEL: How did he decide to move there? Did you have any prior connection to Missoula?

ELLSWORTH: We didn’t really. We didn’t know anyone up here. I think my dad had maybe travelled through Missoula once when he was a kid and had memories of it. But he just suddenly had this really strong feeling, like he woke up one morning with the word Missoula in his head, thought he remembered it being in Montana, and then went and found it on a map. Then, after not too long, he came up here by himself and scoped it out and found us a place to live and then we all moved up. I remember it being a really sudden kind of unexpected thing.

SOBEL: Was it a difficult adjustment for you?

ELLSWORTH: I remember feeling strange about it. It’s definitely a completely different kind of atmosphere from LA. Even now when I go back down to LA, I get a lot of childhood memories coming back to me. Like just being on the highway in traffic reminds me of being a little kid.

I also remember noticing the differences in the people and feeling strange, though I wasn’t really able to pinpoint it. For example, when I look at my kindergarten school book, I’m one of the only white people in my class. So there was more diversity (in LA), whereas, in Missoula, there’s a lot less diversity, and I remember feeling like that was odd somehow. Like there wasn’t much of a mix of people around me.

SOBEL: Can you describe the neighborhood where you grew up in Missoula?

ELLSWORTH: Well, in fourth grade my parents actually bought a house with the help of their parents, but when we first moved here we lived in a duplex. It was in a small neighborhood, walking distance from the school that we went to. We were also right by the train so I remember playing on the tracks a lot when I was a kid. There was a lot of industrial stuff around us, too, like big dirt piles and weird yards full of construction equipment. My brother and I would sneak around there and climb up dirt mounds and go adventuring. There was also this empty lot right by our house where the plows would pile all the snow from the neighborhood so every winter there was this gigantic mountain of snow that we would dig tunnels through. It became kind of a communal fort for all the neighborhood kids.

Actually, the house my wife and I just moved into is about five or six blocks from there.

SOBEL: You mentioned that your father did work with the elderly. What was his job when you moved up there?

ELLSWORTH: He organized the Meals on Wheels program in Missoula and also helped with a number of other services for homebound elderly. He also did a lot of hospice work.

SOBEL: Did your mother work?

ELLSWORTH: Well, she was a stay-at-home mom in Los Angeles, but when we moved to Missoula, she was working for a place called Opportunity Resources that was basically services for people with mental disabilities. So they both basically did social work.

SOBEL: You mentioned a brother. Do you have other siblings?

ELLSWORTH: Yeah. My brother is two years older and I have a sister who is eleven years younger.

SOBEL: So you’re the middle child.

ELLSWORTH: Yeah, although I was the youngest for eleven years. My sister was kind of unexpected.

SCHOOL

SOBEL: Can you talk about what school was like for you growing up, especially as a new student in a small town?

ELLSWORTH: School was something I never felt like I completely adjusted to or fit in with. I mean, I remember enjoying the first school I went to. It was a smaller school and I guess grade school in general is easier, but then I went through the typical rough time in middle school and high school.

I guess I’ve always been a pretty avid daydreamer. I feel like I’ve had a lot of almost out-of-body experiences while sitting in classrooms, like getting weirded out by the sudden realization that I’m sitting in a classroom full of kids all the same age as me and all facing the same direction. I’d have experiences where the teacher would just seem to not be making any sense to me at all. I guess drawing was sort of like a place to put all that restless thinking energy. I would just tend to completely space off into these whole trains of thought and forget I was in the room, but when I would sit and draw, it would sort of anchor me somewhere and I could pay attention. But then I would get in trouble for drawing because no teacher would believe that I was doing it as a way of paying attention.

SOBEL: When did you first start drawing?

ELLSWORTH: I was always sort of the class artist. I was always drawing pictures and whenever an assignment had a drawing involved, I would suddenly be a lot more invested.

But it was really in high school that I feel like I got onto the track that led me to where I am now. That’s when I really started seeing drawing as a way to figure myself out. It became more of a thinking tool, I guess.

It was sophomore year in high school when drawing became really important to me. Before that it was important, too, but I guess in high school I just got on this new track. That’s when I started drawing things that surprised me. It felt like the drawing was a little more out of my control, so it got exciting because I didn’t know what was going to come out the next time I sat down with a pen.

SOBEL: Did you ever have any formal art training?

ELLSWORTH: I was originally thinking of going to an art school and I even took a couple classes at the University here just to see if that was something I would want to do, but it was just so regimented and…all the critiquing and steering in different directions. They didn’t want me to draw because oil painting was a more serious art. I felt like every natural inclination I wanted to do was basically considered bad art at school, so I realized I needed to find my own way.

SOBEL: Can you describe how you taught yourself to draw?

ELLSWORTH: Well, when things got more serious in high school, I started letting myself doodle and do more stream-of-consciousness stuff. When I was younger I’d want to draw really well, and I’d have a specific image in my head and would try to draw it exactly and get frustrated that I couldn’t do that. But in high school I just started filling pages with lines, and just coming up with stuff on the spot, and I feel like the style I have now is completely mutated out of that.

I guess the actual learning just came from doing it a lot and seeing how my hands naturally wanted to move, and what kinds of characters wanted to come out. So I just kept at it, and it just slowly turned into that. I look back at really old drawings of mine and I can still see my style sort of evolving from there.

SOBEL: Was there something specific that happened in sophomore year that made you commit more seriously to drawing?

ELLSWORTH: Yeah, sort of. At the time I was rolling with this rowdy group of skater kids and we were up to no good. We would go around town and get up to mischief, and I reached this weird point where I realized I didn’t really like myself when I was with them. I guess it was just in general the way they were towards other people. I started feeling embarrassed that those were the people I was hanging out with. So I reached this weird point where everything just snapped and that summer I stopped hanging out with them.

After that, I went and bought some pens and just started drawing all these geometrical figures, and then drawing crowds of characters, and then slowly the geometrical figures merged with the characters, and those drawings gave me this sense that I could be an individual and not worry about what a group of kids thinks of me. There was something about tapping into my drawing that helped me feel like I could stand on my own and not worry about anyone else’s opinions. I guess it was my way of circumventing the whole high school drama of fitting in. And as soon as I did that I ended up meeting a lot more interesting people.

SOBEL: Did you do anything with the drawings that you were producing at that time?

ELLSWORTH: They were mostly just for myself. I would fill sketchbooks with them. In my senior year, I had a couple of friends who were really into drawing, too, and the three of us would do this thing where we each had the same size notebook and we would work in them and then we would alternate and respond to each other’s drawings. That was the most collaborative thing I did.

I always wanted to make comics but I would never get very far when I tried to sit down and do that. I didn’t know how to create a narrative or have forward momentum in my drawings. The closest I got was drawing a crowd of people with some word bubbles for what everyone was saying. But they were mostly just loose drawings or notebooks filled with drawings.

SOBEL: Were comics a part of your childhood and teenage years?

ELLSWORTH: Oh yeah. Definitely.

SOBEL: What were some of your earliest exposures?

ELLSWORTH: When I was really young I was obsessed with Spider-Man. Another one of my early childhood memories was in kindergarten and the teacher went around the room and asked us each what we wanted to be when we grew up, and I said I wanted to be Spider-Man. <laughs> I didn’t know that that role was already filled. I thought I could really be Spider-Man. <laughs>

I had this Spider-Man shirt that I was completely obsessed with. I had to wear it every day, and I wouldn’t let my parents take it off me so they had to sneak it off me and wash it when I was asleep and then put it back on me. <laughs>

But I don’t really remember seeing actual comics at that time. I think I just thought that Spider-Man was a real person. I also remember going to the Galleria, the huge mall in Los Angeles, and meeting Spider-Man. He was there signing autographs. That was another big experience, actually meeting the real Spider-Man. <laughs>

When we moved to Missoula, I remember some of the older kids in our neighborhood showed me some comics. I think one of the first comics I looked at was an Incredible Hulk comic, which, at the time, was like a completely alien experience. I remember flipping it open and seeing that villain, the Leader, who was this little green guy with a gigantic forehead, and just having never seen anything quite like that before.

There’s something about the way comics looked to me when I first was finding them, like in first grade. They felt so beyond me and so alien. It was this thing that the older kids were into. I still feel like I’m trying to recapture that feeling of what I thought Marvel comics were like when I was a kid, as opposed to what they ended up seeming like in hindsight. But, all through middle school and high school, I was pretty obsessed with comics

SOBEL: Were you a collector?

ELLSWORTH: Yeah. There’s still all these long boxes of comics in my mom’s storeroom that she wants me to get out of there. <laughs>

SOBEL: Was it mostly superheroes or other stuff as well?

ELLSWORTH: Mostly the superhero stuff was all I really knew. There wasn’t a comic shop here at all for a long time but there was this new and used bookstore that had a little comic section. I had a file with them and would sign up for different comics and my brother and I would concoct all these chores that we would do for my parents to get money to buy them. Then, when we were a little older, we ended up starting our own business mowing people’s lawns so we could keep up with our comic habit.

SOBEL: What were some specific titles you collected?

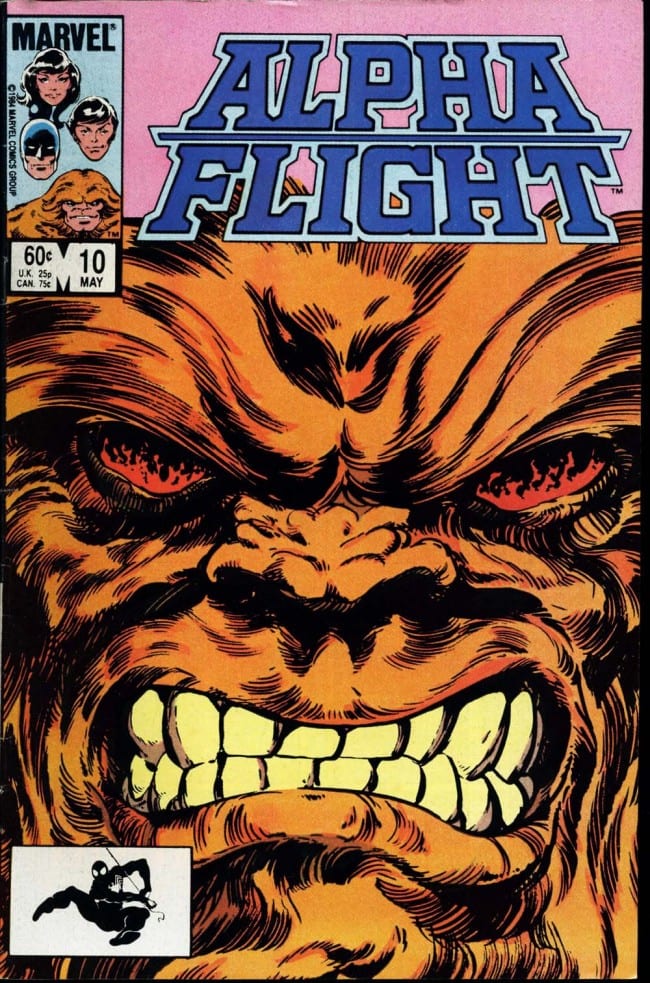

ELLSWORTH: I was pretty into anything with mutants for a long time. I still remember the first comic that I actually bought myself. It was Alpha Flight #10.

SOBEL: John Byrne.

ELLSWORTH: Yeah, I totally loved his stuff when I was a kid. I still love all those old comics. But that one…I remember I was walking to the 7-11 to buy candy and I saw this big scowling Sasquatch face on the cover of this comic book and ended up buying that instead of the candy. <laughs>

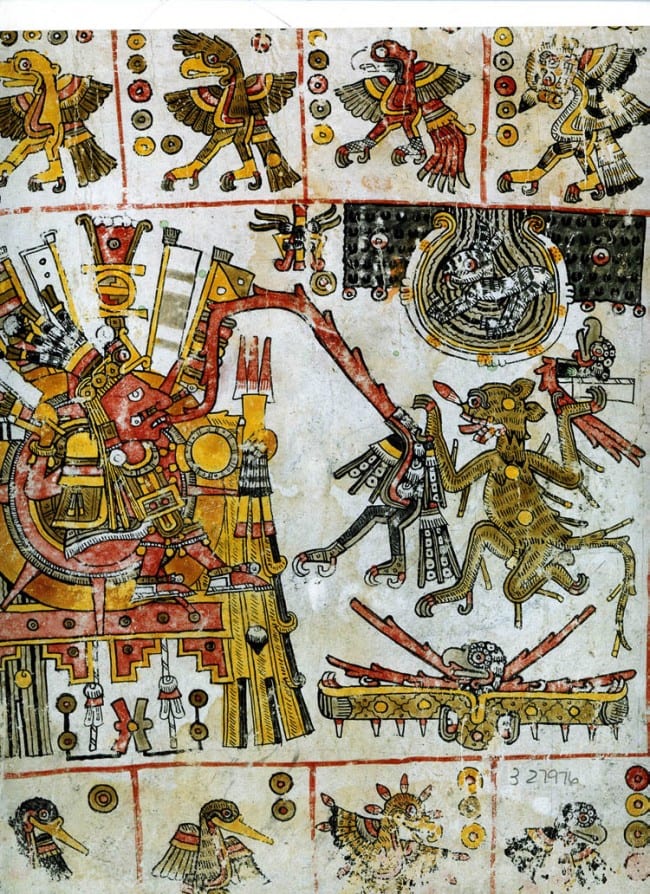

Another specific comic that I remember really well is New Gods #9, a Jack Kirby comic. Something about that one kind of haunted me and for the longest time I could never find any other issues of it so it was just sort of this weird standalone, kind of strange, alien experience for me.

SOBEL: Was that your first Kirby comic?

ELLSWORTH: Yeah.

SOBEL: What was your impression of it?

ELLSWORTH: I remember feeling like there was something frightening about it. There’s all these human-sized insect people scrounging for food in these tunnels, and then there’s this scene with Orion where his face is completely scarred from battle and he just gives this long monologue, and then all the furniture starts flying around the room for some reason. <laughs> I remember it seeming really intense. It was like the most intense possible characters doing insane stuff. And I loved the boldness of his art and all the colors, too. I remember staring at that one a lot.

But those two artists…the John Byrne ‘80s stuff that he did on Alpha Flight and Fantastic Four, and all the ‘70s Kirby stuff, I definitely still look at. I love looking at the art and the weird concepts and colors. It definitely gets me really excited about comics.

SOBEL: What about books. Were you a pretty avid reader as a child?

ELLSWORTH: I was. Yeah. With actual novels, it took me a while to be able to have the attention span because there was something about having words and pictures together in comics that really held my grip. I would read them and really study every picture. With novels, I remember I would have to picture every scene in my head really vividly in order to feel like I could grasp it. So I was a very slow, but really visual reader.

SOBEL: You’ve talked about Dr. Seuss as one of your main influences, but I was wondering if you were also influenced by Maurice Sendak?

ELLSWORTH: Yeah, definitely. I don’t know how direct it is but I get compared to Maurice Sendak a lot. I never really feel like I’m directly taking from him, but I do have really vivid memories of being read Where the Wild Things Are when I was a little kid. My parents only ever had like a couple of Dr. Seuss books but the drawings in those really affected me too. And same with the, I don’t even know the name of the illustrator, but the guy who illustrated all the old Wizard of Oz novels (John R. Neill). Those had really amazing, almost like art-nouveau fantasy art in them. I remember poring over those when I was a kid.

I also always loved being read to. My mom had a ritual of reading to us every night when we were really little. She read all the Wizard of Oz books and the Narnia Chronicles and stuff. I remember laying there just watching it all like a movie in my head.

CAVE DWELLING

SOBEL: After high school, you kind of drifted around the country. Can you talk a little bit about that period of your life?

ELLSWORTH: Well, I actually left high school early. My senior year, I started getting more and more disillusioned with the school system and started to feel like I didn’t know how to function in any kind of normal way. So I quit, got my GED (graduate equivalency degree) immediately, and then hit the road. I was living out of my car off and on for quite a long time. I was just exploring the United States. I feel like that was my own weird kind of schooling. Just seeing the world first hand and living on the outskirts. I was just filling up sketchbooks with drawings and trying to figure out what I wanted to do.

I had a tiny bit of inheritance that I got from my grandparents that was supposed to go to school, and that’s what my brother put it towards, and is now in lots of debt <laughs> whereas I used it by living extremely meagerly, spending the funds for gas and food. I don’t really have any regrets. It definitely was a shift when I realized I needed to come back and be part of the world again, and that I had no job resume. <laughs> But I knew that I really wanted to be able to tell stories with my art. I talked about that a little bit in Capacity, about coming back to Missoula and selling my car so I could focus on trying to make comics.

SOBEL: How long were you out on the road and where did you go?

ELLSWORTH: Well, there were a lot of different stints. I travelled with a girlfriend for quite a while and we did a giant loop around the United States. I spent some time in upstate New York, Florida, and New Orleans. I also camped extensively in Arizona and lived in a couple different caves for a while when I was there. I also spent a lot of time along the coast of California. I was in the Big Sur area, which is actually a great area to live out of your car because there’s lots of hidden pools and waterfalls and places to climb back into. I used my car as my little home base and moved all over the place for a while. I would come back to Missoula now and then to regroup.

SOBEL: I know you talked a little bit in Capacity about living in caves, but can you describe what that experience was like, why you did that, and what you got out of it?

ELLSWORTH: It feels like so long ago, I’m not even totally sure why, in some ways. I was camping out in the Coconino Forest in Arizona, which is kind of this red rock desert wilderness, and one day I was just climbing up around the rocks and…I guess I should say I also have a connection to that area because my grandparents on my dad’s side lived there when I was growing up, so I spent a lot of summers in Sedona and their house was just a couple houses away from desert wilderness. So I spent a lot of time as a kid climbing back and finding caves and exploring around there. So it’s a landscape I feel really connected with.

So, when I was travelling, my grandparents no longer lived there but I wanted to go back and see that area again and ended up camping for a lot longer than expected. There’s this one area that I particularly like that’s probably eight miles out of the nearest town and five miles up this really rugged dirt road. At the very end of it there’s this trail that leads to this big natural arch and I was camping back there. I ended up climbing up these cliffs and finding this really incredible cave with a waterfall going over the mouth of it, which ended up being a temporary thing because when it rains there, everything floods, and waterfalls appear. The waterfall vanished after a while, but I ended up camping in that cave for quite a while.

To me, it was definitely an important time in my life. There was something about being really far away from any kind of human-made structures and the quiet out there. I also loved having time to think and living on an abstract, surreal landscape with all these red rocks that had been carved by the wind and rain for millions of years. The Anasazi Indians lived there and there were actually paintings inside the cave, like these old handprints from the Indians.

SOBEL: Wow.

ELLSWORTH: I also had a lot of strange encounters with the wilderness. There were a lot of wild boars out there, and ring tail cats, stuff like that. That was just a strange time in my life I needed to have I guess.

SOBEL: Do you think it helped you focus on your artwork? Did it give you any clarity in terms of what you wanted to do?

ELLSWORTH: Yeah, I think so. I definitely feel like it’s an experience I draw upon a lot still. When I look back on the art that I did during that time, it looks completely terrible to me, but…

I feel like I’m kind of a hyperactive thinker and drawing has been my way of being able to slow everything down and focus on one thing at a time. So, a lot of the detail that I do becomes my own thinking time. And during that period, I just felt like I was trying to figure out how to think clearly and how to place myself in the world and how I wanted to be in the world. There was something about my experience in high school that made me feel like I needed to step away from all the roles that were inevitable. I didn’t want to stay and become a defeated person. I wanted to figure out how to make my art the center of my life and not take on a bad job, so I feel like that was my period of really getting to know myself from the inside out.

(Continued)