From The Comics Journal #204 (May 1998) and #206 (August 1998)

Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez (nobody calls him Manuel) is unique even among his fellow underground cartoonists, certainly one of the most individualistic and disparate group of artists of any artistic movement of this century. Consider, for example, that he’s a working-class Marxist who actually worked in a factory; he was inspired by the work of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko; he belonged to a motorcycle gang and welcomed violent confrontation.

Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez (nobody calls him Manuel) is unique even among his fellow underground cartoonists, certainly one of the most individualistic and disparate group of artists of any artistic movement of this century. Consider, for example, that he’s a working-class Marxist who actually worked in a factory; he was inspired by the work of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko; he belonged to a motorcycle gang and welcomed violent confrontation.

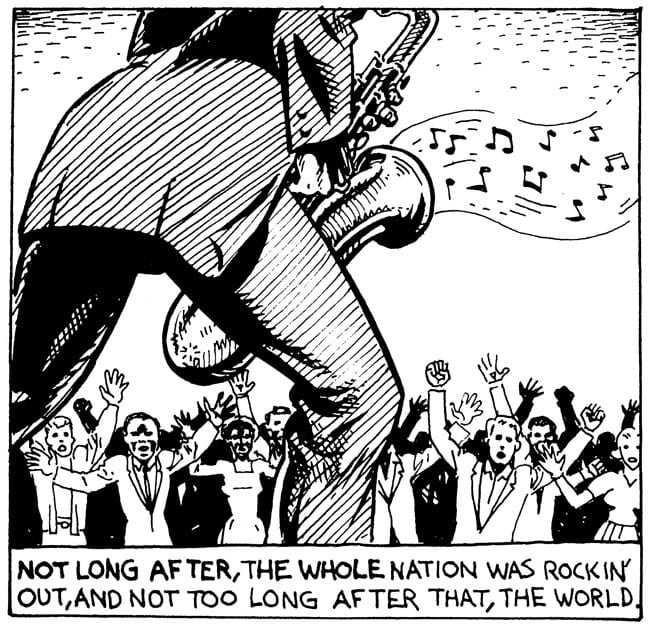

His first strip was published in 1967, an incoherent, psychedelic strip (by his own admission) called Zodiac Mindwarp that appeared in New York’s East Village Other. Before moving to San Francisco, he created “Trashman, Agent of the Sixth International,” a pulpy parodic Marxist character, equal parts sex and violence. In San Francisco, he hooked up with Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Robert Williams, Gilbert Shelton and Victor Moscoso to become one of the regulars in Zap. In the ’70s he started drawing autobiographical and historical strips, which appeared in various underground publications such as Arcade and Anarchy.

He was also a bit of a late bloomer (he was 27 before his first strip was published), which gave him the advantage of having lived a life full of incident and youthful indiscretion, which he would later recount in his comics. His work is usually considerably less internal than that of peers such as Justin Green and Robert Crumb — another anomaly among underground artists (and even post-underground, or alternative, cartoonists such as Joe Matt or Chester Brown).

His latest major works have been collaborations: Boots (written by Jim Madow), a paranoid conspiracy/mystical thriller of sorts; and Fantagraphics published Nightmare Alley, the 128-page adaptation of the novel by William Lindsay Gresham.

This interview was conducted over four sessions in the months of January and March, 1998. The interview begins this issue and concludes next issue. All images © copyright Spain unless otherwise noted.

-Gary Groth

THE IMPRESSIONABLE AGE

GARY GROTH: I think you were born and raised in Buffalo.

SPAIN: Right.

GROTH: I understand that you started drawing in the second grade —

SPAIN: Right.

GROTH: And that the comics you read when you were a kid included Captain Marvel and EC comics.

SPAIN: Right.

GROTH: And you stopped reading comics when the Code was instituted around ’53 —

SPAIN: Yeah, ’53, ’54. You could still get stuff like Johnny Dynamite and One Million BC; I think those were the last ones to hold out against the Comics Code.

GROTH: Could you tell me a little bit about what your upbringing was like? Your father was an auto —

SPAIN: My father did collision work, repaired car bodies.

GROTH: You were born in ’40 —

SPAIN: I was born in 1940.

GROTH: So the war was over by the time you were 5. Do you recall the war having an impact on you?

SPAIN: Yeah. I was at an impressionable age, and I remember all that war stuff that was going on, I remember the various phases of the war. Even though I got it through newsreels and movies, and that sort of thing, it had a big impression on me. I had older cousins who were in various branches of the armed services.

GROTH: I assume your father wasn’t involved.

SPAIN: No, my father, and me for that matter, we were just born at a time when we missed wars. It seems that wars come with a certain schedule, and both me and my father were just lucky to miss them — my father was too young for World War I and too old for World War II.

GROTH: Were you too old for Vietnam?

SPAIN: Yeah, I was too old for Vietnam. I had actually gotten a 4F, you know.

GROTH: That right?

SPAIN: Yeah, I worked hard to get it.

GROTH: When did they start drafting for Vietnam, in ’64?

SPAIN: Yeah, it must have been around ’65.

GROTH: You would have been 25.

SPAIN: Yeah. They sent me down to get a draft card in the early ’60s, but I had just lost my driver’s license. I wasn’t about to fight for them if I couldn’t ride my bike, so ...

GROTH: [Laughs.] Right, right. That’s reasonable.

SPAIN: So I just checked off all the stuff that I knew they couldn’t check up on. Except that I was gay. That was the one I couldn’t quite check off on.

GROTH: You wouldn’t go that far?

SPAIN: I wouldn’t go that far. But I said I pissed in my bed, and I had the clap, I got depressed and tried to commit suicide, and all that stuff. They sent me to a shrink, and everyone said, “You can’t bullshit this guy.” The psychiatrist was asking me leading questions. It was really easy to bullshit him. I could tell the guy didn’t like me when I walked in, it was that sort of thing, so it was easy to know what to say ...

GROTH: Where was this, Buffalo?

SPAIN: This was in Buffalo, yeah.

GROTH: So you stayed out of the war in order to protest it here?

SPAIN: There was no war going on at that time.

GROTH: When was that?

SPAIN: That was in the early ’60s, so there was no real war. But at that point, I was already aware of the bullshit nature of the “established order,” so I wasn’t about to fight to preserve it — even though all that military stuff did, and still does, hold a certain attraction for me. The Army saw that I was the kind of guy that they didn’t want in the armed forces.

GROTH: You have sort of a love-hate interest —

SPAIN: Yeah, I have a fascination with that sort of thing, war, and all that stuff, which is basically history. I remember the first time I read a book of military history; it was clear to me — this is really what history is.

TAKING HIS LUMPS

GROTH: So would you characterize your dad as basically working-class?

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: What was your upbringing like, what was your childhood like? Was it pleasant?

SPAIN: I had a lot of good times. I certainly took my lumps. My neighborhood had various ethnicities, it was an Italian neighborhood, a Jewish neighborhood, and a black neighborhood. The block I lived on was mixed, but if you went to the Irish neighborhood you had to worry about getting punched out by the Irish bully, the Jewish neighborhood you had to worry about getting punched out by the Jewish bully, the black bully, or the Polish bully, or —

GROTH: What were your parents’ ethnic backgrounds?

SPAIN: My mother was born here, but her family is Italian, and she grew up in Italy. My father’s Spanish. In Buffalo there’s a Spanish community, but it’s spread out; there’s no real Spanish neighborhood. Where I grew up there were all kinds of different people — Irish, Polish and Greek —

GROTH: Did they form cliques, like New York City?

SPAIN: Not so much in my neighborhood. The guys who grew up together were the real formation point. Even though most of us were from Catholic backgrounds, they wouldn’t let us into the Catholic Cub Scouts, but they would let us into the Jewish Cub Scouts. Jews were more liberal. For the Catholics, we were just bad kids. But what happened in the Jewish Cub Scouts was that all the bad Jewish kids ended up being in one den with us, and all the good Catholic kids and Protestant kids were in another den with the nice Jewish kids. And then there was this kid ... a Jewish kid, who was a Boy Scout. He was in charge of the bad kids’ den; he tried to foment a revolution. I don’t know, we were probably 11 or 12 or something like that, we were pretty young, and somebody was talking about having a revolution. We were going to split off from the nice kids’ den. We were all very earnest about it, we even wrote up Declarations of Independence. But each time we tried to make the edges brown (so it would look more official), we would burn up our document.

GROTH: You were in the Jewish Cub Scouts?

SPAIN: Yeah, right. Eventually they got tired of us and threw us out. You know, all the bad Jewish kids and all the bad Christian kids, that’s what became our gang.

GROTH: I thought you were a Boy Scout as well.

SPAIN: No, not really. I got to a few Boy Scout meetings, but at that point I was pretty much getting into being a juvenile delinquent.

GROTH: Did you like the uniform?

SPAIN: The uniform was kind of square ... the Cub Scout uniform was kind of like the cavalry in the cowboy movies. The bandana, the blue uniform and all that stuff.

GROTH: Yeah, right. I was always very excited on the day we had Cub Scout meetings because I went to a Catholic school and had to wear a white shirt, tie, the works, and the day of a Cub Scout meeting I could wear my Cub Scout uniform to school.

SPAIN: I went to religious instruction.

GROTH: You did?

SPAIN: Yeah. My family was not that religious. My mother was nominally Catholic ... but there was a church on the corner, so I just started going, I just got into it.

GROTH: On your own?

SPAIN: On my own, yeah. And my parents just let me go.

GROTH: At what age?

SPAIN: Probably from about 7 or 8 to 11 or 12.

GROTH: What prompted that?

SPAIN: I wonder, but it just seemed — it was an impulse to be “good.” Religion lays out a framework — if you want to be “good,” do this. As a kid, it seemed to make sense. Obviously, a lot of adults are doing it. You would go to the confessional, and you would have these little sins to confess. You’d have to think them up, because you forgot them: I disobeyed my parents seven times. I swore nine times.

GROTH: Right, you just have to guess.

SPAIN: Right. In this half-assed, backward way they prompt you to lie. Who can keep track of all that stuff? And things like ... you ate meat on Friday. What are you going to do? This is what your mom cooks. [Laughs.] One of the things that turned me around was ... I was making my Confirmation, and the nun’s instruction was you were supposed to go up to the communion rail and cut a round corner, but the kid in front of me cut a square corner. I thought maybe I heard it wrong. So I cut a square corner, too. I was temporarily confused. The nun snatched me out and sent me down to Father Bent, who was an ex-wrestler and a drunk. I came into raw contact with God’s hierarchy, and, I thought, being a good Catholic, he had some special insight from God, and if I sincerely told him the truth, everything would be OK. So I went down there without a sense of trepidation, and I told him what happened, and he just wasn’t hearing it. “We know you, you’re a wise guy.” And as a matter of fact, in religious instruction I was always pretty well behaved. I wasn’t going there because I had to, after all. But he just went through this whole Gestapo act and suddenly I realized that this guy didn’t have any insight from God. So it was a revelation ... the scales being lifted from my eyes, that this guy didn’t have any special knowledge, so it just opened the door to questioning ... well, if he doesn’t have any special knowledge ... And, in fact, the guy was a fool. What does this imply about the institution he represents? Even at the time it seemed very comical to me that he was making a big stink over some minor bullshit. I could see that this guy was a whole lot stupider than me, man. This was my first insight into the phoney pretentiousness of official authority. [Laughs.]

GROTH: You were 11 or 12?

SPAIN: I was 11 or 12, yeah.

GROTH: Did that pretty much end your interest in religious instruction?

SPAIN: Well, I still went to religious instruction ’til the next grade. Sister Richard was the teacher ... funny these names that they have. I sat down on the first day of instruction and suddenly she comes over and starts to flail away at me with a ruler. And I said, “What? What did I do?” She says, “That inkwell’s crooked.” When I told her that it was that way when I took my seat, she was not appeased. All she had to do was mention it, and I would gladly put it any fucking way she wanted it. Between this and the crazy “Square Corner Incident,” it was pretty clear that the Catholic Church was run by a bunch of sadistic loonies (and I hadn’t even read any history yet). At that point, I realized, “I’m not going to that crazy place.” [laughs.]

GROTH: You did not go to a parochial school?

SPAIN: No. My parents, especially my old man, were not especially religious.

GROTH: Were they agnostic? Or were they just indifferent?

SPAIN: A little of both — my mother was nominally a Catholic, but in terms of my dad, the Spanish experience with Catholicism is not a happy one, you know, they have an especially nasty history. My father just had no identification with the Catholic Church, but he was sufficiently in awe of authority in general that he didn’t express any overt hostility; on the other hand, he wasn’t about to support it if he didn’t have to. As a kid I remember him making anti-religious statements, but it wasn’t a big thing in my household. But on the other hand, some kids would have to go; I guess you did.

GROTH: Yeah. Seven years.

SPAIN: What was your experience like?

GROTH: I remember it vaguely being oppressive, but I also remember not really knowing any different. So when I would raise my hand and ask to go to the bathroom, and they said no, I eventually accepted these kinds of oppressive tactics as being the norm. I don’t remember any serious religious indoctrination, even though I went to a parochial school for seven years. I think it was possibly because I was just too oblivious to it or bored by it to absorb it, which might have been for the best.

SPAIN: Yeah, I think that Catholicism is so dogmatic that it just goes over most people’s heads. What’s interesting is that they tried to extend the Spanish Inquisition into the countryside, but they just lacked the manpower. Most people’s lives were just so much of a hand-to-mouth existence that they just weren’t intellectually sophisticated enough to be heretics. Local priests would advise people what to tell the inquisitors so they wouldn’t stumble and say something that appeared heretical.

GROTH: But you went through a few years where you did go to church, and you did —

SPAIN: Yeah, I would go to church every Sunday.

GROTH: So what did you get out of that?

SPAIN: Eventually I went through a period where I tried to go to church, but I would tend to fall back to sleep and end up missing mass entirely. When I did manage to make it, I tended to nod out.

GROTH: During the church ceremony?

SPAIN: Yeah ... at some point I had art appreciation class in high school, I must have been maybe 13. So going to church became more interesting, because I could check out the architecture and stuff like that. That lessened some of the boredom. But after I hadn’t gone for a long time, or I had gone really sporadically, I went to “confession” and as a matter of fact it was the self-same Father Bent who was in the confessional and I told him I had missed mass about 30 times or something like that and he said, ‘“Why?’“ And I said, “I’d try to wake up for the 9 o’clock mass, and I’d fall asleep, same for the 10:30 mass and so on and I always oversleep.” There was a stunned silence. And then he went into some a long rant about how God had done all this stuff for me and I couldn’t even give him one lousy hour. He gave me — I forgot all this — 25 Our Fathers and 25 Hail Marys, but by that time the whole framework was just so obviously fallacious that I didn’t even finish them. I was told that when you walk out of confession you always feel better than when you go in. I remember even as a kid, coming out of confession and thinking, “Well now, honestly, do I feel any better?” And I would have to answer, “No, not really, if I’m going to be honest with myself,” which is what I understood you should be as a religious person.

GROTH: So it did not give you the guidance you had hoped for? Were you searching for absolutes? Were you searching for some sort of standard to measure yourself against?

SPAIN: I guess that’s what it was. Yeah. My case is a little unique, not having been pushed into it, volunteering for it. But it just seemed to me as a kid, not being very sophisticated, I wanted to be good, and I guess as you say it was some sort of standard by which you could define yourself as good. As you get older, you increasingly see the evil of the world. This seemed to be a way to attempt to counter that with some personal goodness. The first teacher I had in religious instruction was a very nice nun ... you know, she was like some nun out of the movies, a very kind old lady who expounded a very benign religious ideology, so it seemed cool.

GROTH: Now, your dad was working-class. Was he politically aware?

SPAIN: He was kind of a Cold War democrat. My parents were somewhat paranoically anti-Communist. Most people were at that time. My mom became a Republican at some point.

GROTH: Your mom?

SPAIN: Yeah, she’s read Ayn Rand, which — you’ve read Ayn Rand.

GROTH: Uh-oh.

SPAIN: She realized it was meant for her, you know.

GROTH: Is that true?

SPAIN: Yeah, that’s what I think as I look back. On the other hand, she was more open to discussion than my dad. My dad would kind of get pissed off if you offered a rebuttal to what he would say. But he was basically a working-class guy, and the first time I voted, I voted for the Socialist Labor Party. My dad told me it was a vote for Rockefeller, you know. [Laughs.]

GROTH: You’re wasting your vote.

SPAIN: You’re wasting your vote, yeah. The counterargument is that it’s better to vote for something that you want and not get it than to vote for something you don’t want and get it.

COMICS AS A KID

GROTH: So what was your interest in comics like when you were growing up? Was it intense, or was it —

SPAIN: Yeah, intense. I’d read Captain Marvel religiously, and even joined the Captain Marvel Fan Club.

GROTH: Is that right?

SPAIN: Yeah. I was always searching for good stuff. I got that photojournalist’s review of comics, and I found the cover in there that scared the shit out of me. There was a store on the corner that would have a big stack of comics; I would go through that stack once a week. That’s where I saw that cover that just sent chills down my spine. My dad really didn’t like comics.

GROTH: For all the standard reasons?

SPAIN: For all the standard reasons. So I had a whole struggle just to be able to read comics. It happened at an early age, so by the time I was 10 or 11, I had established my right to read comics. I didn’t bring crime comics into the home, and avoided them, because I knew that my parents would really disapprove. But I liked Air Boy; Air Boy had a lot of imaginative stuff in there. As did Captain Marvel, and it’s funny how Captain Marvel was more imaginatively written than Superman. Superman always seemed kind of mismatched. He would punch out guys who were robbing banks, or numbers rackets, all this petty stuff, and he was bullet-proof; it seemed a little unfair.

GROTH: There was a lot more latitude in Captain Marvel? A lot more charm and humor? A richer fantasy?

SPAIN: Right. I remember a story about some guy from another planet who wanted to take the Earth’s resources, because they were running out of resources on his home planet. So Captain Marvel went back and checked the guy’s planet out, and they had cars that had 56 cylinders. Captain Marvel decides that the alien was not worthy of the Earth’s resources. I remember being intrigued by that idea, so I was attracted to stories that made you think about the world in unconventional ways. Then I discovered EC comics.

GROTH: Did you read Captain Marvel prior to EC; did your interest evolve into EC?

SPAIN: Yeah. Well, I’d seen them around. I mean, it’s funny how comics would go through periods where it didn’t seem that there were too many good comics around, so you’d be looking around trying to find something that was cool. I got into Captain Science for a while. I didn’t know who Wallace Wood was, but there was something about his drawing that stood out. My family went to Spain. I must have been about 11 or 12. On the way back, the ship stopped at Halifax, and I went into a used-book store, and they had a Weird Science with no cover. I looked at that, man, and I was just knocked on my ass. The story was intriguing, the artwork was better than anything I had seen. After that, I just started buying that stuff, grabbing it up.

GROTH: Before we get into your EC interest, when you were growing up, what were your other interests as a kid? Were you into sports?

SPAIN: Not so much, but I went through drawing phases of everything. I went through the French Foreign Legion, pirates, spacemen, knights ... Teaching a class ... I taught for five years at the Mission Cultural Center, and I’d see kids’ interests. And they just don’t have those things I had when I was young. They just have superheroes. They do all kinds of stuff with superheroes. A lot of the kids are really kind of bloody-minded about it, too. One of my students did a great strip called Blood Hunter. The hero, of course, had big blades coming out of his hands. Lots of murder and mayhem.

GROTH: More so than when you were a kid?

SPAIN: It seems like it.

GROTH: Was it fairly innocuous compared to today?

SPAIN: I guess, but it was more varied, too. I mean, you understood that things were probably a little bloodier than what they were showing in comics. But on the other hand, there was a greater variety of subject matter, it covered a wider historical period, instead of this monoculture.

GROTH: Gunga Din?

SPAIN: Yeah, Gunga Din. I don’t know whether I ever quite got into that until I saw those great John Severin stories in ECs, but that stuff was around.

GROTH: How do you feel about the sort of narrowing that appears to be going on in kids’ culture?

SPAIN: I think it’s too bad. I understand what the problem is. There’s always a search to try to find something that’ll catch people’s attention, and all that superhero stuff has really been going on for a while. I was really disappointed that the new Two-Fisted Tales didn’t come off.

GROTH: How do you mean “didn’t come off?”

SPAIN: Well, you know, they only put out two issues. It just seemed that if that was handled better, that it might have stood a chance. There really is a lot of great historical stuff, tons of stories that are as weird and as intriguing as you can get.

GROTH: Were you into history when you were a kid? I mean, pre-juvenile delinquent?

SPAIN: No, not so much. It was ECs that developed an interest in history in me.

GROTH: That would have been Kurtzman’s war stuff.

SPAIN: Yeah, right. At the time I got into Hannibal, and Hannibal’s father, too.

LIFE OF CRIME

GROTH: Now, you would have been 10, 11, 12 when the EC stuff?

SPAIN: Yeah. Right.

GROTH: So in fact you would have been starting to be interested in history before your juvenile delinquent phase, which would have been, I guess, post-18?

SPAIN: No, no, it was kind of from about 13 to —

GROTH: To approximately now.

SPAIN: [Laughs.] 13 to 16. After they suppressed ECs, they had Picto-Fiction. Around this time I saw a stack of comics behind the counter in a drug store with a Picto-Fiction comic on top. They had that cover by Jack Kamen of the kid in a leather jacket with the switchblade. And I kept waiting for them to put it on the stand; about a week went by and the stack remained unopened behind the counter. I finally asked the clerk when he was going to put that particular book on the rack. And the guy said, “We’re not going to put it on the stand because it makes juvenile delinquents. Are you a juvenile delinquent?” And I said, “Fuckin’ A.” I guess that was a transforming moment.

GROTH: You liked that because it was a romanticized image of ...

SPAIN: Some sort of recognition of disaffected youth like myself. At that time, my whole neighborhood was getting into that kind of rebellion. The whole neighborhood went on a crime spree that lasted until we were 16, when everybody got busted, and after that ... there were guys who became hardcore criminals. One guy, a guy I got busted in a stolen car with, made it to the top of the FBI Wanted list.

GROTH: Tell me a little bit about your criminal career.

SPAIN: Well, it was just juvenile delinquency; it was us against the world. We’d just go to other neighborhoods and rob the department stores, and then there was a big car-stealing spree that lasted for almost a year.

GROTH: Tell me how that worked. You’d break into a car?

SPAIN: Yeah, you’d get into a car. Well, things were a lot looser. A lot of cars would be open, there were certain cars that you ... well, you’d get under the ignition and put some tinfoil or a church key or something, start them up, and this got to be a big thing.

GROTH: What would you do with them?

SPAIN: We would joyride, and do damage, run them into walls, run them over cliffs and stuff like that.

GROTH: And this career lasted between the ages of 13 and 16?

SPAIN: No, I was 15. It just lasted a few months. It lasted maybe a half a year. But I got busted ... this guy had stolen this car for my birthday. We were driving around the zoo and the back wheel came off, and I tried to help the driver, he had fallen out of the car, and I tried to help him across Delaware Park. They nailed us, and they eventually nailed the other guys a few weeks later. I said I didn’t know the car was stolen, and I got off.

GROTH: Were you ever arrested during that time?

SPAIN: Well, one time the cops took me home for playing chess in this little park area. The cop told me to wipe that look off my face, and I said, “It’s my face, I’ll have any look I want on it.” And the guy dragged me home and told my old man that any time I wanted to step outside with him, he would be glad to oblige me. He was a big guy, and I was about 14 or something. You really saw that things were not at all what was portrayed in the mass media ... at least not in our neighborhood. It was just a conclusion that most of the kids of that age came to, that things were extremely corrupt. But of course we didn’t really understand how corrupt they were. When you think about that period that conservatives allude to as some sort of a Golden Age, here you had the head of the FBI who was utterly corrupt, who was in bed with the mafia, just about literally, who was a homosexual denouncing other homosexuals. Hoover wanted a list of every homosexual in America, he was a rabid racist, and the mob, especially in New York, the mob, the mafia had really made inroads into the political machine. And where I grew up there was a general sense of this. We knew about the guy who was about to testify against the mob who had mysteriously fallen out of a 10-story window in a room guarded by police. How did he fall out? They don’t know. I don’t know if you catch any of that history of crime on TV. It’s fascinating, but this sort of thing was folklore where I grew up. Everything seemed to reinforce a deep-seated cynicism. Frank Costello was the guy who had all the political machinery oiled, so that guys like Lucky Luciano could live a luxurious life. So those were the guys who seemed like role models to us, you know. But for me, when I saw the people whose stolen car we were riding in, I felt bad. They were poorer than us. Also, after spending an afternoon in jail, I decided I didn’t want to be a criminal. I had other things to do with myself.

GROTH: So you actually spent an afternoon in jail —

SPAIN: The other kids were under 16, but because I was 16, I spent an afternoon in jail. And then the other guys in the gang — it was really a despicable thing that they did. They ended up hitting this old guy over the head with a beer bottle, some guy’s store that we used to go in and shoplift. And there was no need to do it, because the guy was very old. He probably had Alzheimer’s, and one of our guys hit him over the head with a beer bottle; it was really a rotten thing.

GROTH: What other kinds of things did you do? You stole cars, and actually engaged in robberies?

SPAIN: No, it was mostly shoplifting, mostly petty, juvenile delinquency, that’s all it was. I mean, we would have liked to have been like them guys ... I, myself, probably didn’t have the balls to engage in major crime. Kids came through the neighborhood, and you would shake them down.

GROTH: So what prompted you to engage in that kind of activity?

SPAIN: It was basically hatred for established society. We just saw ourselves in a predatory world and we could trust one another. It was a sense of comradeship among the guys, but anybody else was just a potential victim. That’s the way the world was. The world is there to prey on you, and you have an arena where you can prey upon others. I think that that’s the way that all criminals see things, and that’s the way society is set up, really. It’s just that people on the top put a mantle of respectability upon their predation. But, on the other hand, who are you doing harm to? It’s really the bottom of the food chain, doing harm to this old guy. Mr. Blimey, we called him. Just some old guy, man, who had a store and probably was on Social Security, and here we were, victimizing this guy, and victimizing other people who were just like us. It was like there wasn’t really a class solidarity as such, just more of a solidarity among us guys. Which was a good experience, in itself.

GROTH: There was no class consciousness involved?

SPAIN: In a way, but it was more instinctual than conscious. There was antagonism between the squares and the hoods. Squares were mostly middle-class Pat Boone types. A lot of it was played out in the high school I went to, which was mostly middle and upper class ... my mother always tried to put me with a better class of people, which never quite had the intended effect. [Laughs.]

GROTH: You actually gravitated towards the criminal element? [Laughter.]

SPAIN: Yeah, right. When I was in art school, these were the only people I could really relate to.

GROTH: Now what was it about the social norms and authority that you so despised?

SPAIN: Well, one thing, when they suppressed the EC comics, I could see that any idea that there was freedom — it was like Father Bent; it was a farce. Growing up in America, we are told that we have certain freedoms. You heard a lot about this especially growing up during World War II: we had this propaganda about America standing for freedom. They can never suppress The Vault Of Horror, this is America, it stands for freedom. As you become a teenager — hey, wake up kid. The police would tell you outright, “You have no rights.” Of course there were some cops who were human beings, but I guess it’s the thugs and bullies with a badge that stick in your mind.

GROTH: Were your parents really disturbed by your getting arrested?

SPAIN: Oh yeah, they were really, right.

GROTH: What was your father’s —

SPAIN: Well, there was some point where he couldn’t beat my ass any more. I did get a shot on him, and he understood that the time for me to get my ass kicked by him was over.

GROTH: When you say that, do you mean you actually had a physical confrontation?

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: So what was the subsequent relationship like?

SPAIN: Well ... It was clear that I was no longer a child.

GROTH: Were you ever close to your father?

SPAIN: Well ... In a way, yeah, and in a way, no. I finally came to realize that we really were the product of our respective backgrounds. It was something that took me a long time to realize: my dad just came from Europe, which is more authoritarian. In fact, even here that generation was less inclined to listen to what they regarded as back talk. My dad would have been coming from a more libertarian part of that tradition but, you know, basically you’re not expected to question. You just do as you’re told, otherwise you get your ass kicked. That’s just what it is. But my old man was always trying to do right by me, as he understood it. I was a spaced-out kid and now I’m a spaced-out adult, and to my dad it must have seemed as if he just had to knock some sense in to me. How’s this kid going to be able to survive? He couldn’t articulate that, and it was something that bothered him.

GROTH: So after he couldn’t physically intimidate you, what was your relationship like? How did he deal with these issues?

SPAIN: We would get into discussions, but at some point he would just get really pissed. We’d be watching television, and I’d say, “I hope that the bad guy shoots the sheriff.” Of course he never did, but my dad would get real pissed off at stuff like that. You know, he was a law-and-order, working-class guy, but at that point, I just had a dislike for the established order that I have today. It hasn’t changed. And it’s funny, my kid goes to school, and I understand that she needs an education, and I try to do my best to foster a respect for learning, and she certainly has a good attitude towards school, but my attitude hasn’t changed, man.

GROTH: Do you feel like the odd man out among other parents because you feel this way? As people get older and they become parents, they become more conservative ...

SPAIN: What I try do is to encourage a good attitude toward learning about the world in all of its diverse aspects. This is what’s necessary, not only to survive and prosper, but to have a fulfilling life. My real attitude to official authority is the same as it has always been.

GROTH: Are you making a distinction between a good attitude and your —

SPAIN: And my attitude, right. That’s exactly the distinction I’m making. As a parent, I have to look out for my kid. I want her to know that learning is really fun. You see kids in this neighborhood, and I see people that I’ve known as kids and who have become adults, and I understand how they’ve been cheated because nobody has been able to convey to them the pleasure of learning and knowing things. So I was just lucky, for some reason. I was able to discover that, but not so much in school.

GROTH: You decided it’s a balancing act between instilling a skepticism for authority in your daughter, but dampening that self-destructive impulse which can go hand in hand with that?

SPAIN: Yeah, it can easily go hand in hand with it. I try to do that. In other words, I can’t lie to her ... just like any kid, she’s a kind of establishmentarian. She believes in all this stuff.

GROTH: Is that right?

SPAIN: She tends to. But on the other hand, San Francisco tends to be more progressive than lot of places, so she’s exposed to a lot of good progressive ideas: feminism, peace activism, things like that. She has an attitude that girls can do anything, which is a good thing. It’s often that I just tease her and say, “No, girls can’t do that sort of stuff.” And of course she just completely rejects it.

GROTH: Give her something to rebel against?

SPAIN: Right, exactly.

CONFORMING

GROTH: What other media did you experience in the ’50s? Did you watch television?

SPAIN: Yeah. I used to listen to the radio constantly, and when TV came in, I’d watch anything in those early days. I’d watch Kate Smith, and all the stupid stuff —

GROTH: When did you get a TV?

SPAIN: We must have got a TV around ’52.

GROTH: You were 12, so that means you experienced TV in its infancy?

SPAIN: Yeah, right. And also what I experienced was the anticipation of TV. They used to have those great programs that came on between 5 and 6, the serials. And so just the idea — think of that, man, you can actually see that stuff on TV, like a little movie in your own house. When it finally came, I’d watch it intensely, but by the time I was 14, I hardly ever watched it. I would watch a few things, but it just wasn’t the completely absorbing thing that it was when it first came. My wife complains about my daughter watching TV all the time, but I think that if you let her watch it all she wants, after a while she’ll just get sick of it like I did.

GROTH: You said, “The thing about the stuff you read about in EC comics was that it was incredible. And somehow everything else you got in the media, you just knew it was bullshit, you just knew that even these people who were conformists weren’t really that way, they really weren’t these nice people, they were basically as rotten as everybody else. They somehow put on this goody-goody face. That was everything about MAD comics, MAD comics just got through that shit, and Veronica and Archie and all that stuff, hearing the voice of truth out of all the chaos of smarmy niceness.”

SPAIN: Did I say that?

GROTH: Yeah.

SPAIN: [Laughs.] That pretty much sums it up, yeah.

GROTH: Can you elaborate on what you meant by your reference to the conformist aspect of life in the ’50s?

SPAIN: Especially in high school. In high school you really got it, and —

GROTH: That’s where you really learned to conform?

SPAIN: Well, no. That’s where I learned to rebel. In grammar school, kids are put through that quasi-prison camp routine. And having taught, I can understand why they do that. But I think it doesn’t have to be that way. Teaching kids was some sort of karmic comeuppance. I had all these young boys from 8 to about 12, and they’d just love to bust your chops. I would do my best to answer any question they would throw at me. I would just answer them as straight as I could. Even if they were being a wiseguy. I mean, at some point you might just have to say, “Everybody in this class knows that that’s not a serious question, and you know it, too, and so you’re just taking up time in the class when we could be doing something that’s cool.” But that was a rare occasion. I still basically sympathize with those kids. I see them as kids who were just like me. At some point you might have to clamp down. They tend to get a little too bloody-minded. One time I showed them how to draw action in a sequence of panels. A car coming down the street, and they’d say, “Put a cat in it so it can run over it.” OK, so I would draw a run-over cat. “Oh, put a baby in there.” “Guys, now you’re going too far.”

GROTH: You had to draw a line.

SPAIN: Right, you had to draw a line somewhere.

GROTH: Did you see movies in the ’50s?

SPAIN: Oh yeah.

GROTH: The Wild One was my favorite —

SPAIN: That’s right, The Wild One. I remember seeing it with my parents.

GROTH: Is that right?

SPAIN: Yeah, my parents asked me if I thought what the bikers did was good. My enthusiastic response was that it was. It wasn’t the answer they were looking for.

GROTH: Did you respond to Brando because he spit in the face of hypocrisy and convention as embodied in those simple townspeople?

SPAIN: There’s something about the assuredness they have, in the way they expect you to accept your place as a cog in a productive system, which is not necessarily acting in your interests, or anybody else’s, for that matter. It’s really an insult to your intelligence, that they think you’re too dull to realize that what they’re claiming to be true is just not true. You can see it all around you. You can see that liberty and justice for all isn’t even a pretention with those who represent the law. The Pledge of Allegiance to the flag — I don’t have any allegiance to a flag. I have an allegiance to the concepts of the United States Constitution, the ideals of freedom, those ideas that are enunciated in the great documents. Those philosophical concepts are rational, optimistic ideas that I feel a strong allegiance to. But I don’t feel any allegiance to a flag, and there’s not liberty and justice for all. Under God? Why is it the government’s place to promote religion? Look around the world at places where religious fervor is intense, like Algeria or Northern Ireland or the Bible Belt here where they have all those kid-on-kid massacres. That whole thing spits in the face of the separation of church and state. Instead of the good-natured intelligence that has characterized the best in the American spirit, you have the cult of the flag, which has come to symbolize, especially among its adherents, unquestioning obeisance to authority. These guys are continuously exposing themselves for the pompous hypocrites that they are. Just look at the whole thing about Clinton and Monica Lewinsky. I give a shit whether he had an affair. The real political issue is having some moralistic pecksniff recording your conversations and getting into your personal life. That’s what you have to look forward to if the Religious Right ever takes over America. It’s a preview of things to come. And it’s dawning on people. It’s semi-heartening. The one thing about America, despite our present-day narrowness of vision, is that we don’t see ourselves as serfs.We don’t have to bow to anybody. But the opposite attitude is also there. Some people think that our problems stem from a lack of obedience to officially constituted authority. The ones who scream the loudest about “Big Government” are the same ones whose not-so-secret agenda is creeping Fascism. And the corporate elite will be our new lords. It’s just part of a struggle that’s always going on. Those guys are always going to try and con you. Why wouldn’t they? If you’re dumb enough to go for it, why wouldn’t they? Why wouldn’t they have you pledge allegiance to a flag in order to distract you from the fact that the people in the top one percent income bracket have more wealth than the bottom ninety percent and that’s somehow a meritocracy? We’re suckers enough to let them con us into it. All of their flag-waving is a distraction from this central condition of our existence. While they are quick to invoke the names of the courageous troops who died in battle as having died for “The Flag,” how many of those wars were for propping up corrupt dictatorships who were merely fronts for U.S. corporate interests? As a matter of fact, it was radicals and liberals who fought for free speech against the same right-wing loud mouths that are in the process of gutting the Bill of Rights even as they scream about “Big Government.”

GROTH: Would your conception of liberty and justice for all include economic equality?

SPAIN: Yeah, definitely, right. I think that most people who have a good balance between productive, fulfilling work and pleasure are basically happy. I think people get loaded all the time as a substitute for therapy. They are people who are trying to work something out. While things can and should be set up so that everyone has the material basis for a decent life, including work at decent wages, access to means of improving their skills, etc., some sort of opportunity has to be made to provide circumstances where even the fucked-up can be useful too ... I think everybody, whatever their ideology, wants to see a society of the useful rather than a society of the useless. And I think that there is a strong impulse in people to want to be useful. But the fact of the matter is the capitalist system cannot and does not want to create jobs for everybody. We’ve strayed off from comics into this politics, but it’s a prime motivating factor for my work. I don’t want to be a mainstream cartoonist. I don’t want to have to be a mouthpiece for what I consider unjust. I’ll do commercial work to make bread, but the great thing about doing underground comics is the fact that we can just say it as we see it.

GROTH: Yeah. Of course, the perverse thing now, though, is that the people who are doing mainstream comics really consider themselves to be almost entirely free to do what they want, because that’s what they want to do. So you have that new-found paradox where the kind of crap that people were essentially forced to do for commercial reasons is now being done out of some sort of inner need or inner impulse. [Laughs.] You can’t win, Spain.

SPAIN: I guess probably not.

GROTH: A lot of the corrupt values you’re talking about become internalized over the course of time, and a lot of that has happened over the last 50 years.

SPAIN: Yeah, I’m sure it’s true.

GROTH: You may not follow it as assiduously as I do, but all the people who fled Marvel and started Image did it ostensibly, they say, for creative reasons. And of course they’re doing exactly the same thing they did at Marvel. It’s the same neo-Fascist garbage.

SPAIN: Yeah, right. you’ve got to wonder. I don’t doubt it for a second.

GROTH: False consciousness is I guess what you call it.

SPAIN: Yeah, right. It’s a false consciousness. I have qualms about judging someone’s sincere expression. I feel obliged to defend anyone from government censorship, but I have to say, what that guy [Mike] Diana does, you know, showing young girls being tortured ... that stuff just repels me. I like good action stuff, the violence is OK with me, but the idea that somebody takes any kind of pleasure out of carving up some helpless girl just strikes me as being really somebody who’s fucked up.

GROTH: Now how would you handle the argument that that’s his form of rebellion? I mean, is that valid?

SPAIN: Well, I’m not quite sure what valid means in this regard. If somebody says, “I would like to carve up so-and-so, and just cram their guts up their ass, and fuck them up imaginatively.” Well, short of an overt threat to carry it out, I would have to say they’ve got a right to express themselves. I’ve thought of a story where a cartoonist does a story about a gruesome murder, and sometime later he’s walking down the street and some guy who has read his story ends up murdering him in the gruesome manner depicted in his story. It’s a dilemma. The idea that media creates violence is simply ahistorical. Societies have done unspeakably cruel things with very limited media. Hitler never saw TV. You can just go down the line. The idea that suddenly somebody’s going to do something that they’re not predisposed to do is not very plausible. Tamerlane used to kill everybody in cities he conquered and build pyramids of their skulls; it’s hard to top that. The only thing that media does is to present a concept as opposed to the real act, then you can consider how you feel about what has been presented to you. Certainly no one in the past who had the inclination and opportunity to carry out acts of despicable cruelty was ever deterred by not seeing it in some medium. I guess what media can do is make a case that some particular group, helpless young girls, for example, have it coming. But I think the real issue is access. It’s just harder to sustain an irrational hatred of a particular group when you see people as they really are, even with some of their less attractive features. Maybe that’s overly optimistic, but at some point I’ve hated almost every group I’ve come into contact with. But I find it impossible to sustain my feelings of disdain, because most people are just trying to get along, don’t want to harm anyone and will even help you out if they can. I think that if everyone gets a chance to tell their story we’ll just have a harder time holding all these false notions about one another. On the other hand, maybe it will just reinforce them, but I think it’s worth a shot. Trina [Robbins] tells me I have to be responsible. I’m not exactly sure just what she means. I’m responsible to my own point of view and my own ethical sensibilities.

GROTH: I know that on some level you have to believe that in order to do the work you do, and you must feel that you’re being responsible to your own needs as an artist.

SPAIN: Yeah. Well, it’s hard to differentiate my aesthetic needs from my philosophical commitments. There is a history of puritanism on the left that I don’t feel very comfortable with. I certainly don’t want to live in a puritanical society. But the fact of the matter is that sex orgies are not very democratic. Granny does not get invited to the orgy. Neither do the ugly babes. In some sense the Catholic Church, or any church, is egalitarian in that way, in that the beautiful people get to hang out with the not-so-beautiful people. That’s reflected in revolutionary ideologies that shun that pleasure principle. There’s an element of the pleasure principle that has a consumer’s aspect to it. But, just to show how complicated it is, the standards of beauty that come through mass media leave me cold. Like Jaclyn Smith. There are certain movie stars like that ... they’re beautiful, but I find them unattractive.

GROTH: They’re sexless?

SPAIN: Yeah, they’re sexless. Playboy, it’s the ultimate example. I shouldn’t say that, because we’re trying to get Playboy as a sponsor ... but I guess I have to say it. It seems as though women used to be more sexy in Playboy. They’ve become too smooth or something.

GROTH: I have the same reaction, but I wonder if it’s simply because I’m not 18 any more.

SPAIN: No, I don’t think that that’s it at all.

GROTH: You think that the photographic paradigm has objectively changed?

SPAIN: Yeah, I do, yeah. It’s a contemporary standard of beauty that is bland. I remember seeing a Miss Black America [pageant]. They had women who were overweight, women who were imperfect in many ways, but they were far more appealing and far more interesting. Those women were far sexier because of their imperfections. Perhaps it’s just because I’m a gnarly dude, but I don’t find those flawless women very appealing. I wouldn’t be motivated to hit upon them even if I were younger.

GROTH: It’s almost as if a false standard of beauty keeps evolving in our society. They keep perfecting their bodies, and you have to wonder, to what point? A funny thing happened ... my girlfriend and I were watching The Misfits with Marilyn Monroe, and there was a shot of her running, from behind. And my girlfriend said, “Is my ass that big?” And that was the worst trick question I had ever been asked, because first of all, it’s Marilyn Monroe. Like, how do you criticize Marilyn Monroe’s ass? But the subtext was that ass was too big. You couldn’t win. You know, if I said her ass is not as big as Marilyn Monroe’s, that could be bad. If I said it was, that could be bad, too.

SPAIN: [Laughs.] You had to say, “Your ass should be that big.”

GROTH: Right. Right.

SPAIN: You’re right, there’s a movie with Marilyn Monroe, where she’s an American in some Eastern European country and she’s involved with a prince.

GROTH: The Prince and the Showgirl, with Olivier.

SPAIN: Right. She looks great, man, you can see her belly sticking out a little bit. She’s looking good.

GROTH: Yeah, yeah, I think so, too.

SPAIN: I think it’s part of the age, where everything has reached its point of refinement where it’s devoid of the spice of life. There seems to be big interest in a lot of sleazy ’50s skin books. Like Cad, did you ever see Cad? And you look at those women, and they look like they had a hard life.

GROTH: Been around the block a few times?

SPAIN: Right. But they’re far more interesting. They don’t even show you their whole breast, it will be covered up. But even now it looks sexier, because it’s a big thing that she’d be even showing her stuff. But it’s something more genuine about that scene. It’s hard to idealize it, and you can really get an insight just what the problem of functioning in a hedonistic society is. It’s interesting to me, how the older generation dealt with it. They created an illusion that there was an ongoing crusade of rectitude. On the other hand, as we were talking about earlier, the guardians of righteousness were the gate keepers to a world of unbridled hedonism. The summer of love was only novel because the pretensions were dropped. The wall of illusion that our parents’ generation created was for us, for the kids. They wanted to protect us from the exploitation that seems to accompany those sybaritic scenes despite, or maybe because of, their almost universal attraction. My old man was a respectable, hard-working guy who came home and read the paper. My mom went to the PTA meetings. All appearances in my family were of conventional, if somewhat oddball, respectability. But the whole of society approved of and promoted a drug that is more dangerous than heroin, tobacco. My old man told me that before Prohibition he would drink every so often. And then when Prohibition came he just stopped drinking. And then after Prohibition he would just have a drink every once in a while. There were a lot of people like that. On the other hand, people were and are doing hard time for marijuana, compared to alcohol and tobacco, a relatively benign drug. Back then the most vociferous upholders of public rectitude were collaborating with the underworld, just as today the C.I.A. works with Central American drug dealers to bring cocaine into Los Angeles. The topper is that the “Drug War” is an excuse for dragooning people of the inner city into neo-slavery in the for-profit prison industry of America. I suspect that the reason that you don’t hear much about slave labor in China is that American officials were tired of having Chinese officials laugh in their face. To point out this obvious stuff will still elicit a response of indignation from people who think they have a stake in the illusion of “respectability.”

GROTH: From your vantage point now, do you consider that to be hypocrisy? Or was it a necessary artificial demarcation between ...

SPAIN: I think that when you have a kid you get an insight into the dilemma that most people face. When I work on certain things, I try to cover them up ... not wanting my kid to see them. But my kid has a whole lot of information that she got from preschool. She knows a lot of things that I was unaware of, but in a child-like way. I try to keep the more raunchy stuff out of sight so she can be a kid and deal with the complexities of life when she’s better prepared. It certainly seems as if there is a similar effort on the part of many people to keep the general public in a child-like state, but their motive is clearly the bottom line. I know that the counter-culture world is not a world without casualties. My nephew said to me, “I really like your stuff. I can’t wait to go out and get into a gang fight and stuff.” And I started telling him that he should give some serious thought to the downside of all that.

(Continued)