RESPONSIBILITIES

GROTH: To bring this back to comics and your growing up in the ’50s, all of these conundrums bring to mind Fredric Wertham, who was a paradoxical figure, because he was actually a liberal reformer type ...

SPAIN: They’re the worst, in a lot of ways.

GROTH: Were you aware of him then?

SPAIN: Oh yeah, right; yeah, sure.

GROTH: He was fairly prominent during the outcry against comics in the early ’50s.

SPAIN: Yeah, I was aware of what was going down even though I had never really seen the book [Seduction of the Innocent] until I was an adult.

GROTH: Did you watch the subcommittee hearings on TV?

SPAIN: Some. Yeah, I watched the McCarthy hearings, I watched some of the Kefauver hearings. I never got to see Gaines stand up to them. Now you have William Bennett and C. Delores Tucker. I watched them on TV. It was real interesting. Right after C. Delores Tucker, you had all these guys who had done “studies” that showed when people see media violence, then they go out and murder people. It was all a pitch for reform coupled with an urgent plea to fund these studies and it was obvious that they had had some preconception of what they wanted to prove even before they started these so-called studies. But the underlying assumption was that our most fundamental rights are at the mercy of some asshole’s “study.” The point is that we’re all responsible for our actions. I’m not responsible to anybody for my thoughts. I’m responsible to people for my actions, and everybody’s responsible. If I say, “Hey, it would be really cool to do this,” to commit some atrocity, that’s just not the same thing as doing it. If you carry out a sick fantasy that is tangibly harmful to someone else, we must all see that you receive the appropriate punishment. But if there is no tangible harm, there should be no punishment, period. There was an EC story I read in Tales from the Crypt, it was about some father who had killed his daughter. It was a story by Bradbury, and the implication was that the father killed the daughter. When I read it I went — yechh! If you believe in freedom of speech, you have to believe in freedom of speech for the National Review and Human Events, and all the people you hate.

GROTH: That doesn’t mean that you might not think that what they’re doing is pernicious?

SPAIN: That’s right, I think it sucks, it stinks and I don’t want to read that sort of thing myself ... yeah, right, there’s a lot of stuff like that. It’s a funny thing about that gore and violence. Something like Blood Feast — did you ever see those movies, Blood Feast, and Palette of Blood and stuff like that? They become so bloody that it becomes conceptual art or something like that. Usually I really don’t like movies like that ... I think they’re probably made by some pimply-faced weasel who is thinking, “Good, this is my chance to get back at all those babes who wouldn’t put out for me, and now I’m going to make a movie where the monster comes over and carves them up.” Get out of here, get a fucking life, or learn how to come on to women, or something. I find that sort of gore repulsive. On the other hand, if it’s done well, there are certain things there are certain EC things that I just like, stories done with a sense of satire.

GROTH: When you said earlier, though, that ... well, I don’t know If you said this exactly, but you seemed to think the media didn’t really affect people, you were ridiculing the notion that —

SPAIN: Yeah. I think that if you look at the historical record, you will see that there were always violent people around.

GROTH: The media certainly must have some effect on people; EC had an effect on you.

SPAIN: Yeah, it did have an effect on me, but ... well, it’s hard to know. It’s hard to know. If you had a laboratory experiment and had another me that didn’t have EC, how would I have turned out? People are a bit more complicated than laboratory rats. And again, the historical record is there. A historical record of unspeakable cruelty ...

GROTH: It’s true that people can be violent without media, and historically have been violent before mass media. But, that doesn’t mean the media couldn’t either cultivate or enhance that propensity, right?

SPAIN: But why would you think people are any different now than they were centuries ago? Or what you’re saying is that people have that propensity, but maybe it could be stoked, or maybe it could be smoothed over, if everything was at the level of Archie comics. I must admit, if I lived in a world where all you could take in was Archie or its equivalent, I’d feel the urge to go up in a tower with a gun. I have a clip of all these trailers of teenage movies. And all the American ones, there has to be a fight scene in a teenage movie. In all the English ones, there is never a fight. There is frolicking, and the getting wild, and doing all that sort of thing, but there is never a fight. They’re just so civilized, but ultimately is that the kind of world you want to be in? C. Dolores Tucker’s idea of the First Amendment is that nothing that offends her is allowed, and she’s not quiet about it. This is offensive to me. Offensive? I can’t offend anyone? The whole idea of the First Amendment is that you have a right to offend.

GROTH: Yeah, but I don’t see it as an either/or question. I can concede that the media affects people without conceding that it has to be strait-jacketed by government, or ... well, I mean, it’s already strait-jacketed by everything except government. You know, market mechanisms and special interest groups, and everything else affects the content of media. There are good arguments in favor of an absolutely free media, notwithstanding any pernicious effects it might have on people, because there are also corresponding benefits.

SPAIN: Well, yeah, but I still think that it seems to make sense that somebody who’s inclined to harm somebody is going to harm somebody if they think they can get away with it. I think that it might give them some ideas about how to go about it. Doesn’t it seem as though in any group of people, you’re going to have x-amount of sadists? We seem to always have had that, you know. So, we hire one group of sadists in hope of controlling the rest. Some of the Soviet movies are really sociological and turgid. On the other hand, so is Spit On Your Grave, one of the bloodiest movies ever. And in the U.S.S.R. there were mass murderers running around because of sloppy police work. On the other hand, all that crime stuff is so hyped up. There’s the argument that there hasn’t been this big crime wave. In the first place, cops can determine what is a murder and what isn’t. They certainly have a stake in the public perception of whether the crime rate is going up or down. And why do we always have to pay for their incompetence with our civil liberties? It just seems that the overwhelming evidence is that there is that bloody-mindedness that exists in people and so it gets to Trina’s question: we should be responsible, but I would ask, just what are we responsible to?

GROTH: That’s a good question. For you, as an artist, what are your responsibilities, and to whom or what do you consider yourself responsible?

SPAIN: I’m responsible to my ideology. To my sense of what betters the condition of working-class people like myself. There are some people I would like to punch in the mouth, but it’s so much more civilized to do underground comics.

GROTH: Well, you’re not a pacifist, we all know that.

SPAIN: Right.

GROTH: You have to argue that your ideology has to perform some good, some kind of…

SPAIN: Yeah, right, media.

GROTH: I find it distasteful when I hear William Bennett lecture on virtue. But I realize that that’s because my sense of virtue is completely different from his. [Laughs.] But it does seem important to have some conceptual understanding of virtue, even if it’s just your own, rather than ...

SPAIN: Right. And it’s something ... we all kind of believe in some virtue.

GROTH: Right, right. And it seems like the right wing has actually co-opted terms like virtue and morality, and the left wing is reluctant to use those terms any more, which is unfortunate because it leaves the left in a moral vacuum.

SPAIN: Yeah. What’s especially unfortunate is that there are these values, like solidarity, and compassion, and open-mindedness, and trying to not to be full of shit (something that seems to be completely absent on the right), that seem to be overshadowed in contemporary political dialogue. What they have is a herd of chumps conditioned to salivate at certain authoritarian symbols, and they just play these, and they know that they’re always going to have these fools out there who’ll wave the flag. Iraq, for example: there are all these people who are just getting chubbies over the idea that we can bomb people. And that’s played upon. But everybody’s not like that. There are people who say, ‘We don’t like Saddam Hussein, but what are we doing? Bombing these helpless civilians that we have been starving to death for years.” When what’s-her-face, Madeline Albright, gets up and says, “I’ll bet you I have more concern for the Iraqi people than Saddam Hussein.” How stupid are we? What an insult for that woman to come up with something as stupid as that. So what? Saddam Hussein doesn’t give a shit and she can come up with something like a half-inch turd ... I don’t know, I’ve been violent in my life ... but on the other hand, it was more or less a fair fight, you know? Victimizing the weak, it’s not a good thing. That’s why there should be a free and open dialogue. People are free to criticize me, but I want a chance to respond.

THE STUDENT

GROTH: What kind of a student were you in high school? You went to jail when you were 16.

SPAIN: Well, actually I just spent an afternoon in the can. I don’t want to over-dramatize.

GROTH: Did you ... live by yourself after that?

SPAIN: No, I stayed home and graduated high school. There were certain subjects that I was really absorbed with, history and art. I had to do a term paper for American History, and I started reading about Hannibal. I started reading everything I could find about him, about the Punic Wars, about Hannibal’s father ... to this day I can run down battles, give you historical dates ... it was just something that I found utterly fascinating. And I was always good enough so I could pass. I’m sorry I didn’t take more math, because a lot of that stuff seems more interesting to me now. But I was able to get along, pass, get a high school diploma. But there were certain things that really intrigued me, and I had some good teachers. I had a teacher in eighth grade, her name was Miss Whetstone, and she was red-haired, and she had eyes that bulged out of her head. And she was known as a no-nonsense teacher ... the frightening visage of this woman with these eyes that popped out of her head with this red hair. You knew, when you saw her in action a few times, that when you went to her class, you behaved. But she was also a very compassionate woman who was very serious about her students learning. She would give us mimeographed sheets of sentences to dissect ... I can do this ...

GROTH: You mean diagram?

SPAIN: Diagram the sentences, right, that’s what it is, diagram. And to this day, I can do them. If you give me a sentence, I can diagram it. Every day, man, you just had to do it, and she didn’t want to hear that you couldn’t do it. But she was a woman who would actually talk to you. “How come you guys have that hair style?” But on the other hand, despite her genuine compassion, you just knew that you couldn’t cut up in her class —

GROTH: Right. In one sense, the best of both worlds.

SPAIN: Yeah, so I was fortunate to have people like that, who brought to your attention the fact that there is an alternative to hanging on the corner, staring dully and drunkenly into the void. These poor kids, you see them, and nobody did that for them. Learning about the world is a pleasure, it’s not something that you should have to be whipped into as a kid or as an adult. And so that’s the sort of thing I tried to get across to the kids in my class, and my daughter. .. well, I try to impart that to her, even though I can still feel my resentment of what seemed to me then and now as mindless regimentation ... . What can I tell you?

GROTH: I understand. My kid’s only 3, so it’s a long way to go.

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: With these conflicting impulses.

SPAIN: That’s right. It’s just a fact of life, man. If you’re not knowledgeable, if you’re ignorant, then you’re going to be a victim. So there’s power that’s accessible, and if you don’t grab onto it, you’ll wish you had.

GROTH: Better to be a knowledgeable victim than an ignorant one.

SPAIN: [Laughs.] Right. If you’re a knowledgeable victim, at least you have a chance of striking back.

GROTH: Didn’t you join the bike gang right after high school?

SPAIN: No, I went to art school for three years.

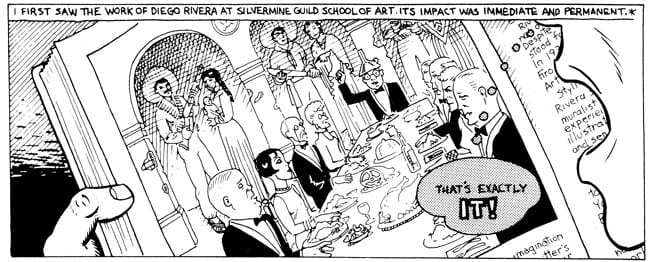

GROTH: Let me just skip back. You attended the Silvermine Guild School of Art of New Canaan, Connecticut?

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: Now, when you did that, you had not yet joined the bike gang?

SPAIN: No.

GROTH: What is the Silvermine Guild School of Art?

SPAIN: It was an art school in Connecticut that ... one of the people who started it was John Vassos, the guy who designed the Lucky Strike logo. At the time I didn’t realize that. He was one of the prominent guys in industrial design ... so there were a lot of good teachers there. But of course it was the time when Abstract Expressionism was dominant. The work I did in the commercial art class was appreciated, but the fine arts course was a different story.

GROTH: Why did you choose that school?

SPAIN: My mother ... she just figured if he stays in the neighborhood, he’ll probably end up in jail, so here, he had something going for him ...

GROTH: Send him to Connecticut. [Laughs.]

SPAIN: So I’ll send him to Connecticut. That’s where people are nice and nobody gets drunk. So I went to Connecticut. In Buffalo, there were no drugs in my neighborhood at that time. When I was a kid, nobody smoked grass, but in Connecticut, man, there was everything, even heroin. But I didn’t touch it. I was serious about getting an education.

GROTH: You were 18 when you —

SPAIN: Seventeen, yeah.

GROTH: — left home.

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: Did you revel in your freedom?

SPAIN: Well, it wasn’t much freedom compared to Buffalo, because I was living out in the country, I didn’t have any car, and I didn’t have any bread, so I just kind of. .. I was just at that age I didn’t really know how to hit up on girls ...

GROTH: Did you get a job in high school? Did you work?

SPAIN: Yeah. I had a paper route, so ...

GROTH: Didn’t clerk in the local hardware store?

SPAIN: No, I was an usher. .. my old man had a gas station, for a while I worked ... so I made enough money to have ...

GROTH: Did you date in high school?

SPAIN: Yeah, right, I did, a little bit of dating. But still ... it kind of takes you a while to understand how to hang out with girls, and how to approach them in the right way. I’m kind of a crude dude, so it took me a while to figure it out.

GROTH: Yes. To learn that ritual.

SPAIN: Yes.

GROTH: Was sex a verboten subject in your family? What was your parents’ —

SPAIN: Yeah, I don’t think it was generally talked about. When I was 16, my old man told me about the clap, that you could get the clap, and you should wear condoms.

GROTH: He told you that?

SPAIN: Yeah. He remembered some guy in the ’20s, and he was called the sheik, and he had a lot of women, but he just died in pain in the hospital. Probably before they had penicillin. [Laughs.] It was a great story: “The Sheik.”

GROTH: Didn’t Rudolph Valentino play the sheik?

SPAIN: Yeah, right.

GROTH: Were you an only child?

SPAIN: No. I have a sister.

GROTH: Oh, you do? Older or younger?

SPAIN: Younger.

GROTH: How did she affect the dynamic of the family?

SPAIN: She was the good kid and I was the bad kid. [Laughs.]

GROTH: And how did you two get along?

SPAIN: When I was younger, there was a certain amount of resentment that she was always held up as an example of what I should be.

GROTH: How much younger?

SPAIN: About three years.

GROTH: So you were pretty close in age.

SPAIN: Yeah, by the time we got to be teenagers, she had ... there were a lot of friends that I would try to hit up on.

GROTH: That could be useful, right ... Was there any sort of sibling rivalry?

SPAIN: Well, me and her have our philosophical differences, but ...

GROTH: She was not rebellious, or ...

SPAIN: No, she was not rebellious. But you can have a good discussion with her ... she was real bright in school. I just cut the swath through grammar school and high school, all these teachers hated my guts, and she would come along, they all loved her. These teachers, at the mention of my name, would grit their teeth. But Cynthia ... she is real bright. She said that when she finally got her PhD, it was the first time that she had difficulty learning anything. Learning always came easy to her. Finally she had to absorb all this stuff, and it was difficult for the first time in her life. But she plowed through and now she’s a PhD. I’m real proud of her.

ART SCHOOL EXPERIENCES

GROTH: Tell me a little bit more about the Silvermine Guild School. You were there for approximately two —

SPAIN: Three years. I split a couple weeks before the end of my third year.

GROTH: What did you learn there? Was it a good experience?

SPAIN: It was a good experience all in all, because I got to do things. I got to do sculpture, I got to do oil painting, I got to do drawing ... well, I was always doing a lot of drawing, but it was a depressing experience for me, for various reasons. One of the things was, I was always a hotshot as an artist. I could think of myself as the best artist on the horizon. And even in art school, I thought of myself as the best, except maybe for M.K. Brown, who was in my class. She was the one person whose work I saw as being as good if not better than mine. But draftsmanship was not held in high esteem, so that was difficult for me, and I was the one who made those determinations as to what was good or bad. Drawing was always something that I could retreat to, and I found myself in a situation where people who had a different philosophy were judging my work. If somebody could correct my work, and make it better, in my eyes, fine, but to them, my work was too tight. It is tight, but that’s the way I like it.

GROTH: You once said, “When I was in art school, it was the period of trying to figure out what was going on, also coming into contact with anarchist books. I started picking up books and reading all this different stuff.” It sounds like you really started broadening your horizons, or at least educating your own intuitive ideas with concrete ...

SPAIN: Yeah. The art school was pretty much art. After a while, they had a course survey of Western civilization that was pretty good. But I just got into philosophy by reading.

GROTH: A little Kierkegaard, a little Gramsci ...

SPAIN: Yeah, right. And Hegel and Kant, pouring through all that stuff.

GROTH: This was more or less on your own?

SPAIN: Yeah. I had a lot of time on my hands, although there was never a dull moment. The first year I was there, my landlady tried to shoot me.

GROTH: Shoot you with a gun?

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: Now why would she want to do that?

SPAIN: It’s a long, complicated story. Someday I’ve got to do a strip about it. There were a bunch of interesting characters involved. I don’t know how to give a brief synopsis of it. These people were alcoholics. Some years before, the father was delivering a grand piano on a trailer; his son was in the back of the trailer. The father took off quick, the kid fell off, and the grand piano hit him in the head. The doctor said that there was a chance he might live, but he would be a vegetable. He not only lived and wasn’t a vegetable, he was a bright guy and got a scholarship to Penn State, which is when I moved into the house. But he had this fist-sized dent in his head. There was this other guy there, Louie Duhane, who was an interesting character. He had a poodle and he would break out into interpretative dancing in the middle of the class. The husband, Skelding ... I probably shouldn’t have used his real name. I wonder if any of them are still alive.

GROTH: The worst thing they could probably do is go try to shoot you again.

SPAIN: Yeah, that’s right. I don’t know whether Skelding would, but Mrs. Hammond ... Everything was always tense at the table, because Mrs. Hammond insisted on all these manners. To this day I can dine in polite company, because I know to spoon my soup away from me, and if you fucked up on that, Mrs. Hammond would —

GROTH: I always admired that about you.

SPAIN: [Laughs.] That’s what they say about me. [Laughs.] So anyway, it was always tense at the table. Mrs. Hammond was tyrannical, and both the Hammonds were imbibing huge amounts of booze. At one point Skelding came in, and he forgot to take off his jacket. Mrs. Hammond whipped this plate of relish across the table, they were seated at either end of the table, and it bounced off Skelding’s head. The relish was coming down his face, and he looks at Mrs. Hammond and says, “Calla, you are cheap.” It was like living in the middle of a Eugene O’Neill play. Eating dinner was kind of a tense experience.

GROTH: [Laughs.] “You are cheap?”

SPAIN: “Calla, you are cheap.” And then the funny thing is, me and Skelding hated one another. And at some point, the son — I think his name was Frank — dropped out of school and he came back. He was a pretty good guy. But Skelding was a guilty man, this accident that had impoverished them, they were kind of well-off at one time, but the medical bills had impoverished them, so they were forced to take in the likes of myself as a boarder. Mrs. Hammond was always unkind to Skelding, and he was an intimidated guy. The other dynamic was the fact that me, Skelding, and Louie had no love for one another. And this went on all year. At some point, it was near the end of the school year, Mrs. Hammond and Louie got into an argument over the hamburgers which she liked to leave raw in the middle, and Louie did not like this. So he decided to give the raw hamburger to his poodle. Mrs. Hammond insisted that the middle of the hamburger be given to her dog. So an argument began, and at some point, Skelding sided with Louie. Mrs. Hammond said, “OK, Louie, you’re just renting your room, you can’t use the rest of the house, you can just use your room.” At that point, even though I couldn’t stand him, I sided with Louie. I said, “Well, Louie, you can come down to my room, too.” So it was me, Skelding and Louie versus Mrs. Hammond and her son. You know he had to side with his mom, of course. So she said, “OK, I’ll show you guys. I’m not going to sit at this table until I get an apology from everyone.” For about a week, we were spooning our soup the wrong way, and eating our bread without breaking it in half, wearing jackets at the table, and just cutting up along these lines. Mrs. Hammond had this boyfriend, this rich Italian kid who went to art school. He was a rich biker. He had a leather jacket and stuff. We used to drink together at various times, and he was seeing Mrs. Hammond on the side. Mrs. Hammond had a few boyfriends.

GROTH: How old was Mrs. Hammond?

SPAIN: Mrs. Hammond was about 50, but she was a good-looking woman. She was kind of a beat-out alcoholic. I’m sure in her prime she was quite beautiful. She had seen better days. But this guy ... him and her hit it off, and it was just something that everybody accepted. She also had another son. She had a younger son, who was, I don’t know, 4 or 5. Incidentally, I was the only one he’d listen to. I mean, he’d call his mother a son of a bitch, and was basically kind of an unruly kid, except that when I would tell him to do something, he would do it for some reason. And at some point ... I was eating some extra crackers or something in the kitchen, and the kid came in and said, “You’d better look out, my mom has got a gun and she’s going to shoot you.” And I said — she was in the other room, and I knew she could hear me — ‘Well, if she ever pulls out a gun, I’m going to stick it up her ass.” With that her first son came in and told me to get in my room. I said, “Hey man, I’ll plant you, too.” And he came over to me and said, “Listen, I have to stick up for my mother.” I said “OK.” After all, I had no beef with him. So I went into my room. Later that night, her boyfriend came in and told me he got Mrs. Hammond the gun. So at that point, despite my big words, I made my flight. I got my blanket and went over to the school, and spent a few nights there. Afterward it was kind of settled. Mrs. Hammond wasn’t really mad at me, but she really hated Louie. Even after a year of this woman’s terrorizing and arrogance, I felt a little sorry for her now that she had been taken down a peg. During the week of Mrs. Hammond’s exile, Mr. Hammond became more sexually aggressive, he would whack her in the ass, and make crude references to her, and come on to her in a crude way, and she seemed to like it. It changed the dynamic of the household, where Skelding, instead of being a whipped dog, was a sexually aggressive guy.

GROTH: Like he got testosterone shots or something?

SPAIN: Something, yeah, right. This whole episode seemed to energize him, and this veil of guilt that was draped over this guy’s shoulders had disappeared, and he just became more of a man. I left the house — by that time school was just about over, so ... that was it. I don’t know whether the real names of these people should be used.

GROTH: Well, you know, it can’t be libelous if it’s true.

SPAIN: It is true. Of course, after all these years, I bear these people no ill-will. The second year I was there, I fell in with these guys who were junkies and burglars. Basically good guys, at least as far as I was concerned.

GROTH: You were naturally attracted to them?

SPAIN: Well, it was that I felt comfortable with them. [Laughs.] And they treated me good. However, I saw one of the guys, a good buddy of mine, commit suicide, so ...

GROTH: Jesus!

SPAIN: Yeah, so it was never a dull moment. And in the midst of all this I was doing a lot of artwork. But at some point I just couldn’t do any more artwork there. I finally started doing weird comic-book covers, things like ... one was a bed with a dish and a rag and a severed hand and a knife. I started doing these things that disturbed them, so they sent me to a shrink. She said, ‘‘You really don’t like it here. You really miss being home.” And I said, “Jeez, that’s right.” I had never thought of that. So I just split.

GROTH: You said you left a few weeks before the third year.

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: Did that jeopardize your academic status? You didn’t give a shit?

SPAIN: I didn’t give a shit, and don’t, that’s right. [Laughs.] My academic standing is not really a primary concern.

SEVEN YEARS

GROTH: When you attended the Silvermine Guild School of Art, you were probably between 18 and 21?

SPAIN: 18 and 20, yeah.

GROTH: The first strip that I know you did was Zodiac Mindwarp for the East Village Other. When you attended the Silvermine Guild School, that must have been between approximately ’58 to ’60, and I can’t imagine you did this strip before about ’65.

SPAIN: Zodiac Mindwarp, I did it in ... it came out in ’67.

GROTH: So there’s seven years between the time you attended the Guild School of Art and the time you actually had your first strip published. I want to explore what you were doing in those seven years, and how your interest in comics finally culminated in doing that work.

SPAIN: Well, I always wanted to be a cartoonist. That seemed to be my first love. There was something about art school, they were able to insinuate this disdainful attitude towards things like comics, and towards popular forms of art. Even though I tried to fight it, it seemed to infect me. So I did a lot of painting. By the time I got out of art school, I was fairly depressed, but after getting out of art school, I perked up again and did a whole bunch of painting, and continued to do art work. I’ve always drawn, as a kid, as a teenager ... I was one of those people who drew in the margins of their notebooks and on their pads and on anything I could get a hold of. I got just as much of an art education working at Western Electric for five years as I got at the Silvermine Guild School of Art. During that period, I worked in a plant for about five years.

GROTH: What kind of plant?

SPAIN: We made telephone wire. It was a Western Electric plant. And there were a lot of good artists there, some amazing artists.

GROTH: What was your job?

SPAIN: I had various jobs. I was a janitor at one point, I worked on these different machines, twisters, stranders ... the plant was an amazing place. Janitor was actually the best job, because you got to see all the surreal machines, and all this different wire being processed through the extruders and the spinners and all sorts of things. There were a lot of interesting people there.

GROTH: This was in Buffalo?

SPAIN: This was in Buffalo, yes.

GROTH: You went back to Buffalo as soon as you got out of school?

SPAIN: Right, yeah.

GROTH: And you got a job at the plant pretty quickly?

SPAIN: I got a job fairly quickly, yeah. After a few months. I worked with my dad a little bit, but ... I got a job at Western Electric, and went through the various departments ...

GROTH: How did you feel about working there?

SPAIN: I enjoyed it. A lot of it was tedious, but there were a lot of good artists there. There are a lot of good stories that I could tell about working there.

GROTH: Were you unionized?

SPAIN: Yeah. There was a good union there, CWUA, that stuck up for me. You had to fuck up the same way three times to get fired, and I never fucked up the same way more than once.

GROTH: So you could fuck up three different ways and not get fired?

SPAIN: You could fuck up twice the same way, the third time you were out. I was actually rather creative in the ways I fucked up, but I would never do the same thing twice.

GROTH: So what was your interest in comics at the point you were in art school, and afterwards at the plant? Were you still reading them; were you trying to draw them?

SPAIN: No, I wished often something good would come out. There was a comic that came out, it must have been at the end of the ’50s, called something like Korak of the Stone Age. I’ve looked in the Photojournal Guide to Comic Books; I haven’t been able to find it. It’s not Turok, Son of Stone, even though it sounded like that. But it was this stream of consciousness story about a bunch of cavemen who get lost inside some volcano, and off-the-wall things happen to them. It was really strange, and even though it was Comics Code, I got every issue I could get my hands on, because it was just so experimental, and it was just so imaginative. It was an insight into the potential of comics. They had broken out of that frozen superhero monster et cetera et cetera to do something that was crazy, so that was a forerunner, to me, of the potential. And I always wanted to do comics. It seemed to me as though comics afforded anybody the opportunity to put forth any sort of philosophy they wanted. A good example of that is the guy who did Dr. Strange —

GROTH: Steve Ditko.

SPAIN: Steve Ditko, who did Mr. A, a very right-wing, crazy view on things, but still the guy certainly doesn’t have the conventional point of view. In the plant, there were guys who were great artists. There was Ron Walazeusky, who did beautiful pornographic drawings that were a combination of S. Clay Wilson and Japanese prints. One was of two sailors, one sailor boffing a chick in the mouth, and the other porking her in the butt. His nemesis was a little old guy named Georgie Etsel, who reputedly was for Hitler during World War II. He was a little old guy with no teeth, and he would keep washing these pictures off the wall, and Walazeusky would keep upping the ante by bringing in markers and various materials that were harder to wash off. And Georgie Etsel would find some new solvent to go wash these real works of art off the bathroom walls. And finally Walazeusky carved these beautiful pornographic pictures with a church key on the bathroom walls. The authorities in the plant flipped out and they had photographers down there taking pictures of it. I wonder if any of those pictures are still around. But Walazeusky was a genius. I don’t know what happened to him, but his work was really beautiful. I got just as much of an art education working at Western Electric for five years as I got at the Silvermine Guild School of Art.

THE ROAD VULTURES

GROTH: Tell me what your life was like during that period, both in terms of how your interest in comics coalesced, as well as what else you were doing.

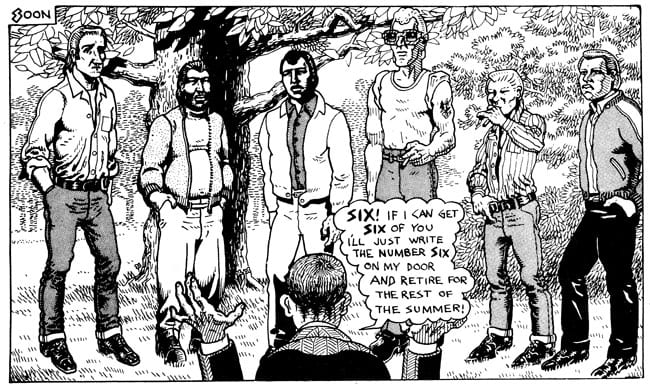

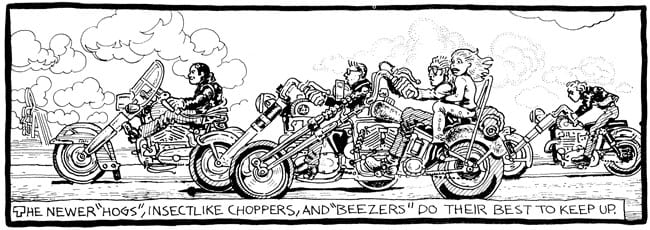

SPAIN: Well, at the time I was riding motorcycles. I had different bikes, and I ended up joining the Road Vultures.

GROTH: Now explain how you joined the Road Vultures; what kind of a bike did you get? How did you gel into that milieu?

SPAIN: Well, Buffalo is a great party town. Every time I go back there, all the bars are jumping, and there’s bands and people dancing, especially at the end of the ’50s and in the early ’60s, Buffalo really had a great blues scene. There were people from different neighborhoods that were into this scene, and they would get to know each other, sometimes even on good terms. A lot of times you’d get into fights with other neighborhoods, but you’d usually end up drinking with these guys that you had fights with last week. I was already working at Western Electric, it was the spring, and I saw these motorcycles takin’ off and I had some money saved in the bank. I said, “I want one.” I had a friend who had a motorcycle. His dad taught him how to ride. His dad stopped riding when he drove a bike in between these two trees and skinned off the side of both of his hands. At that point he figured it was time to stop. So his dad had taught him. He was a big blues buff like me. John Biye, a Cajun guy from Louisiana. He taught me how to ride. Some time later, a guy I knew, a guy who had a motorcycle, got jumped and beat up. A whole bunch of us, at least so I thought, went down to this bar to find the ones who had beat him up. I walked into the bar with two other guys, and we assumed that there were a whole bunch of guys behind us, but there weren’t.

GROTH: You mean you thought friends of yours were backing you up?

SPAIN: Yes, we thought there was a whole bunch of us behind us, but when we looked around, we were three guys in this hostile bar. I was fighting five guys, and I kept on fighting even when they knocked me down, and some guy kicked me in the head. At that point I just curled up in a little ball, and let them beat on me. There wasn’t anything else I could do. It was amazing how little it hurt. I mean, when you’re getting kicked in the head, that hurts, but it’s amazing how resilient the human body is — and how much a leather jacket protects you, actually.

GROTH: A padded motorcycle jacket, right.

SPAIN: But when the Road Vultures heard about it, they thought that that really showed class. They went down to the bar to find those guys, who were long gone by that time. You had to strike for the club, hang around for a certain amount of time, and then they’d vote on you, whether they wanted you in. So I got in in two weeks, and became a Road Vulture.

GROTH: Well, you’ve got a number of comics stories that harken back to that period, or even before, and I wanted to know how truly autobiographical these stories are. You did the stories in the ’70s, so I’m kind of skipping around here a little, but the first story that I wanted to ask you about was “Dessert,” which I think was supposed to have taken place in 1954, which would have made you 14.

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: In which case it hardly seems likely you were actually involved in that story.

SPAIN: Yeah, we went through this brief period of rolling fags; our neighborhood went through cycles of crime, and this was one of them.

GROTH: Were you involved in this, or did you only hear about this?

SPAIN: Well, no, I was ... well, I guess the statute of limitations has run out. Yeah, sure.

GROTH: You were a participant?

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: So you were 14 when you were involved in sexually abusing and beating up a gay guy. Were the other kids older? In the story it certainly looks like they’re closer to 18.

SPAIN: Yeah. Well, they were kind of a mature 14. By the time we got to be 18, all that stuff was considered beneath us.

GROTH: I see. So rolling fags was one of your activities.

SPAIN: For a short time. But anyone approaching us, even on a non-sexual basis, did so at their peril. In 1954 ... the thing that surprised me back then was that a lot of police were sympathetic to gays.

GROTH: Huh! That strikes me as.. . almost contradictory.

SPAIN: Uh, yeah.

GROTH: I would’ve thought the police would probably have approved of that activity.

SPAIN:You would think that they would, but no, a lot of police, even in Buffalo, aren’t morons.

GROTH: Another story that I’m curious whether it was autobiographical or not, is titled “How I Almost Got Stomped Through ‘The Still of the Night’ by the Five Satins,” which describes someone attending a concert and sitting in the chair of a black guy’s girlfriend, and the black guy comes up and basically says, “That’s where my girlfriend sits,” and the guy says, “I’ll get up when she gets here,”and he says, “No, you’re going to get up now,” and he says, “Yeah, well, why don’t you just go fuck yourself?” And he finds himself facing 30 black guys. Was that you?

SPAIN: That’s completely autobiographical, yeah.

GROTH: That was you?

SPAIN: That was me.

GROTH: That was supposed to be ’55, so you were 15 at the time?

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: So you were like a real tough guy?

SPAIN: Well, I certainly fancied myself as that.

GROTH: You got into a lot of fights ...

SPAIN: I got into some, yeah.

GROTH: You must have been something of an anomaly in the underground scene; I don’t imagine most of the underground artists were the kind of guys to get into fights.

SPAIN: It’s ironic that they thought that comic books were causing juvenile delinquency, when most juvenile delinquents didn’t read comics, or much of anything. I remember a guy from my neighborhood reading Studs Lanigan, but he was unusual. I used to read science fiction. But reading wasn’t ... or even going to college, I think there was one guy who went to college, but most guys didn’t go to college. The black guys in my neighborhood were more into higher education than the white guys.

GROTH: Were the Road Vultures ... I mean, was that a fairly violent way of life? Or is that exaggerated?

SPAIN: You’d find a bar to hang out, and everything would be cool for a while. But after a while, guys would get bored, and somebody would always eventually come in and get things going. I mean, you didn’t have to look for fights, because somebody always wanted to give you a hard time, because you had long hair, or you had an earring, or something like that. They ended up getting their ass kicked. So there were two ways you could be a nonconformist. You could be a nonconformist and just adopt a Buddha-like attitude of accepting all kinds of abuse, or you could be a Road Vulture.

GROTH: I assume you read Hunter Thompson’s Hell’s Angels.

SPAIN: I read parts of it. I never got through the whole book.

GROTH: Is that right? I was going to ask you if you thought that was a pretty accurate depiction of a biker gang.

SPAIN: Yeah, the parts I read were pretty plausible. It’s interesting that the incident that the movie The Wild One was based on was some sort of minor unruliness that took place in Hollister; the Road Vultures had a far bloodier episode in Sherman, New York, where somebody lost an eye ... at least one guy did time because of that incident.

GROTH: Were you there at the time?

SPAIN: No, I wasn’t. This was before my time.

GROTH: How many Road Vultures were there?

SPAIN: Oh, somewhere around 20. So we pretty much kept to ourselves, and —

GROTH: Can you give me an idea of the social routine? Would you all get together Fridays or Saturdays?

SPAIN: Yeah, we’d have a club meeting once a week, and we’d hang out, depending on what bars would let us in. There was one bar that always let us in, the Silver Sails, that was run by Ma, who would always serve us. It was down by the Niagara River, at the end of the Erie Canal, and we could always count on Ma to let us in. And some weekends would be dead, and sometimes you could go in there on a Tuesday night and the place would be jumping, so that was where we’d hang out in the winter, and then when spring happened, there were all sorts of things you could do — go for rides to different places, and various field meets, and motorcycle events.

GROTH: I don’t want to sound naive, but was there any political dimension to joining the Road Vultures?

SPAIN: Well —

GROTH: Or did you just want to kick ass?

SPAIN: Well, there were two phases of the Road Vultures. I used to read The Weekly People, which was the official organ of the Socialist Labor Party. The format of The Weekly People was set around 1911. It had very large pages. When I rolled it out, it was hard not to notice, and it had a great logo, the arm and hammer logo, a muscular arm wielding a hammer with block lettering across “The Weekly People.” You could always get into a discussion by just pulling out that paper and sitting there, somebody would always give me an argument about it, and then if you refuted their arguments, they would complain that you’re always coming around here with these socialist arguments, and you could tell them, “Well, I was just sitting here reading my paper and you came in here and started bothering me, so stop whining.” I used to argue a lot, and they would tell me things like, “Them Negroes, they move into your neighborhood and you know how they are, they’re always drinking causing crime and they’re dirty and they’re loud, and we don’t want people like that around.” I always assumed that prejudice was fairly ingrained. Then something happened that shed a different light on things. They used to have a big field meet in Cuba Lake; it was in what they call the southern tier of New York. What happened was there was always this big dance the night before, and there were a lot of college guys who hung out in that town. There might have been a university or some college around there. It was as though there was an invisible line drawn down the middle of the dance floor, and the bikers would be on one side, and the college guys would be on the other side. This one time, there were these black guys there, maybe about five or six guys, and evidently the college guys had been giving these black guys a hard time. When the black guys saw us, they were really glad to see us. It was like these long-lost brothers. The Road Vultures took these guys around, and made sure that they had plenty of drinks and everything like that, and made sure that these college guys didn’t mess with them, took good care of them. And it was the same guys that would make these know-nothing arguments ...

GROTH: Can you elaborate on the social dynamics there? Because I assume the Road Vultures didn’t take them in or protect them because they were all a bunch of good liberals.

SPAIN: We were outcasts. There was a certain solidarity with outcasts. It’s funny about people. It’s funny about people’s prejudices. What I suspect is, when I look back upon it, I just think that a lot of these guys were putting me on. You know, some guys were really rabid racists, other guys were not racists at all, and even sympathetic to black people being people who were at the bottom of society, like we were, so ... . That was definitely a cultural affinity at that time. There was this one black bike club who always won the uniform prize. If you’re on the road for a few hours, you get pretty dirty, and these guys would roll into town, get some hotel room, and fix themselves up and put on these snazzy uniforms, and just all roll into the field meet, and would inevitably win a prize.

GROTH: Another thing that occurs to me ... I went to school in Rochester, that’s not that far from Buffalo, I don’t think ...

SPAIN: No, it’s 90 miles.

GROTH: And I rode a bike when I went to college there. But one thing I remember vividly is the goddamned cold in the winter. And riding a bike in the winter was insane. The wind cut through a leather jacket as if it were a cotton sweater.

SPAIN: Oh, yeah, yeah. There were a few crazy guys who did that. But sometimes there were mild winters that you could get away with it. I think I kept my bike on the road one winter, that was —

GROTH: It would be really hard to ride year-round.

SPAIN: Yeah, it usually is. One thing you can do is, you can put newspaper under your jacket. That cuts the wind. But one of the signs of the spring is the smell of motorcycle oil. Right around this time, some hardy soul would get his bike out, and you’d smell it.

GROTH: Sort of like a groundhog coming out.

SPAIN: Yeah. A harbinger of spring.

GROTH: So you were a Road Vulture when you were working at the plant?

SPAIN: Yeah.

BACK INTO COMICS

GROTH: So what was your interest in comics and art at that time? I mean, did you have much of one?

SPAIN: Oh, yeah, I drew continuously. At the plant they ended up putting me behind a machine that was always breaking down. They were putting us on time study to put us on piece work, which is in reality a wage reduction. Whenever they would watch us, we would just work slower, and I worked slower than anybody else. And they ended up putting me on a machine that was always breaking down. So I had plenty of time to do drawings. In fact, there was one boss who would chide me if I didn’t draw him a dirty picture every day. He was on the midnight shift, and if I didn’t draw him a fuck picture, he would say, “Where are those pictures? I want to see something here.”

So I got plenty of practice to improve my chops. So the ’60s were starting to gear up, and in Buffalo the bikers merged in with the beatniks and the college crowd, and it became a big party scene. People started getting into Marvel Comics. There seemed to be some sort of psychedelic subtext; it’s hard to put your finger on it. I’m sure other people have mentioned this; there was something that resonated. I remember reading The Fantastic Four, and it was the first time that I picked up a comic book every time it came off the stand since I was a kid. So there was this feeling it was coming back. When they suppressed comics, there were a bunch of us who were EC fans, and there was that cover, the cover of Mad where they were leading the underground cartoonists off in chains, and there was something about that that really resonated. There was this girl in our class, kind of a heavyset girl, her name was Tema, and me and a friend did a strip about her. It was called Tema, and it was written in letters like The Heap. Nasty guys that we were, we put out this strip to terrorize her. We thought of ourselves as underground cartoonists.

Talking to different guys, you’d get a feeling that the idea of underground cartoonists just resonated across the country. Guys I knew would have dreams that they’d walk into some place, and they would see some EC comics that they hadn’t seen before. And I would have those dreams, too. When they suppressed EC comics, I went to every bookstore I knew and bought up every EC that I could find. At some point they actually started charging $3 for them.

It was a funny, mixed feeling about it. It was an indication that we weren’t the only guys who felt these were great, but on the other hand, you had to pay more for them. You used to be able to get them for a nickel. Suddenly they were charging you — even 50 cents was fine. When they wanted $3 for them, we thought they were going overboard.

So anyway, there was this sense out there. This friend of mind, Fred Toote, a guy I did a bunch of strips about in Blab!, was one of them. There was this core of EC fanatics in my neighborhood. There was a sense that something would happen, and suddenly there was this feeling around 1965 that comics were going to come back. At some point, in ’65, I dropped out, I quit work, I had some money saved up, and I went down to the Lower East Side [in New York City] and tried to flood places that would accept my work.

GROTH: You went to New York?

SPAIN: Right. I was right down the street from where Malcolm X was shot. I happened to go to New York that weekend, hanging out with these people. People would say, “Let’s jump in the car and go to New York.” In New York there was a great newsstand on St. Marks and 6th Ave that had everything. You could get The Realist, all sorts of radical newspapers. So I would always bring a bunch of that stuff back, and give them to guys in the plant.

GROTH: You would just drive down from Buffalo to New York, or take a train down there?

SPAIN: I would just drive down, yeah.

GROTH: What was your purpose in visiting Manhattan?

SPAIN: The time when Malcom X got shot I was with a bunch of people, and we stayed in some commune. You’d go down there and get stoned, hang out, and it was just ... being in the scene, you know. Hanging out, basically.

GROTH: Now at some point, you moved to New York for six months, I think.

SPAIN: I moved to New York for a few months in ’65.

GROTH: Does that mean you quit your job?

SPAIN: Yeah, I quit my job. I had a girlfriend at the University of Buffalo, and so when she went on vacation, when she had the summer break, she lived in Long Island, so I just moved to New York so I could be with her. When she went back to Buffalo, I went back there, too.

GROTH: Let me skip back for a second. In 1964, you worked with what you said was an old Commie who was expelled from the Communist Party in one of the purges in the late ’50s, and you put out a periodical called The Spirit and the Sword. This was apparently an underground paper that you’d sell on the University of Buffalo campus.

SPAIN: Yeah, it was in ’64. In ’64, I went to New Jersey. When I came back, the Road Vultures had seemed to dissolve, but there were a bunch of ex-Road Vultures who didn’t want it to dissolve, so we reformed the club. That was a more political time. We would buy coffee for strikers, and do things like that. We were involved in anti-war stuff that was already starting to happen. I was doing things with Ed Wolkenstien, who put out a publication on a mimeograph machine called The Spirit and the Sword, and we would sell it around. The University of Buffalo, they were pretty receptive and I was surprised. I thought, “If you show this to somebody, they’ll probably punch you in the nose.” But people accepted it, and would engage you in intelligent discussions.

GROTH: Can you describe The Spirit and the Sword?

SPAIN: It concerned itself with civil rights, anti-war issues, and I did artwork for it. It would have some historical things, things about John Brown. I learned about John Brown, which is a very interesting story. Everybody knows about the stuff at Harpers Ferry, but what went on before Harpers Ferry, when everybody including the United States government, the United States Army, was afraid of him, is less well-known.

GROTH: Right, right. In fact, the magazine was dedicated to John Brown.

SPAIN: Was dedicated to John Brown, right.

GROTH: His spirit and his sword, I guess.

SPAIN: “The Spirit and the Sword,” it’s some quote from him. That summer I was in New York, I did work for The Militant, which was the newspaper of the Socialist Workers Party. I did some cartoons for them.

GROTH: Was Norman Thomas a presence in your life at any point, or was he —

SPAIN: Well, no. The closest relationship that I had to Norman Thomas was through a bunch of really crazy guys called the Resurgence Youth Movement. Jonathan Leek, who started the Resurgence Youth Movement, was in YFS, which was the Youth Group of the Socialist Party. And when Kennedy died, he issued a manifesto calling for all revolutionaries to go forth with pistol and dagger and put to death all public officials. And he was immediately thrown out of YFSL.

The Yippies were a pallid reflection of these guys. These were genuinely crazy guys. You would see them at a demonstration, and there would be Nazis on one side and cops in the middle, and left-wingers on the other side. These demonstrations always took place in Union Square. These guys would attack the cops. The cops would beat their ass. And they put out this great literature. They would say things like, “We dream of the days when the motorcycles will roar down Park Avenue and the fags will prance on your lawns, and the junkies will shoot up in your bathrooms.” And at the time, that stuff seemed pretty incredible. It was strangely prophetic. One of their slogans was “Arm the Vagrants,” which the Road Vultures took up with a vengeance.

During that summer in New York, I met those guys, and we must have smoked about eight joints, just kept passing around joints. I was really loaded. And they set out to try to outdo one another in these outrageous assertions. They were talking about kidnapping Mayor Wagner’s son and holding a People’s Tribunal. And another guy said, ‘‘Yeah, we’ll build a big guillotine.” They talked about surrounding some reactionary Southern town and wearing these black uniforms, and going in there with submachine guns. I said, “You guys are crazy, the State Police will come and arrest you all.” One guy jumped up and said, “Oh no, we’ll get these big spears, and we’ll sharpen them up and chop off their heads!” Chopping off heads seemed to be big with them. One guy was loonier than the next, but they were interesting. They put out a magazine called Resurgence. It had all this crazy stuff like numerology in it. All this was pre-hippie. So the Lower East Side was really jumping during this time. Buffalo was jumping. That pre-hippie period coalesced by the time I got back from New York in ’67. That’s the winter before the summer of love. And the East Village Other had already been out for about a year. In ’66 we would get bundles of the East Village Other. When I went down there, I made contact with Walter Bowart, he was probably stoned at the time, but he told me to do a 20-page comic, which ended up being Zodiac Mindwarp.

GROTH: He was the editor of the East Village Other?

SPAIN: He was the editor of the East Village Other.

GROTH: How did you get in touch with the East Village Other in the first place?

SPAIN: Copies of the East Village Other would drift into Buffalo. So I went down there. I would get down there, because I would go there for a demonstration, or we’d all jump in the car and just go to New York. I gave him some spot illustrations, and he printed them. At some point, he made this fateful proposition of doing a 25-page comic. His idea was to leave the voice balloons empty, and then we would clip stuff out of newspapers and put them in the voice balloons, which is what we did.

GROTH: A cut-up technique before the cut-up technique.

SPAIN: Well, the cut-up technique — yeah, it was Burroughs’ cut-up technique. At first it was supposed to be a comic book, but the printer he was in touch with didn’t have the set-up to do a comic book, so we made it a comic tabloid.

GROTH: I see. So that was your first published strip?

SPAIN: Yeah, I had done some things for the University of Buffalo newspaper, a strip called Sunny Days. The school newspaper had had a left-oriented staff, and they had got a hold of me. He would crank out a story and I would illustrate it, so I had had stuff published here and there, but Zodiac Mindwarp was the first really major thing I did —

GROTH: Had you read The Beats at the time?

SPAIN: I had read Lawrence Lipton. And I had read a few things. I read a bunch of poetry, and that sort of thing.

NEW YORK

GROTH: When you moved to New York for a while, you said you moved because of a girlfriend?

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: Was this the time you lived in New York when you were roommates with Kim Deitch?

SPAIN: No, this is before that. I just moved there for a few months, three months or something like that, then I moved back to Buffalo. And then I moved back to New York permanently in February of ’67.

GROTH: What were you doing, where you could move to New York for a few months and just move back, and —

SPAIN: At that point I had some money saved up. You could live cheap on the Lower East Side. I could stay with friends, people put me up. I had a period where I just ran into a bunch of luck. First, I had saved up that money, and then I got a job in a drop forge for about three weeks. I ran into guys I knew in high school who worked there. It was really a brutal job. And I suspect that they had looked up my references, and talked to Western Electric, and Western Electric said, “Get rid of this guy.” So they laid me off, and then I had unemployment for about six months.

GROTH: You said it was a drop forge?

SPAIN: A drop forge. It’s the way they make knives and scissors and kitchen utensils. It’s this whole row, they look like guillotines, with this metal block on top. The block must be maybe four by four feet cubed. You have a rod of hot steel. And on the bottom block there are these three molds, where you stick the rod in one mold and press a lever, and this big block comes down and then the block goes back up, and you just keep moving it on until the implement is made.

GROTH: I see. So you had money saved up and took the dive to move to Manhattan.

SPAIN: Yeah. What happened was, I was living on unemployment for about nine months, and some motorcycle accident I had been in a few years before paid off. So I ran into some extraordinary luck, and I was able to brush up my chops and be an artiste, and so by the time Zodiac Mindwarp was published, I was down to 200 bucks, and someone who I thought was a friend burned me for a hundred bucks. He was a junkie, he just died recently. He promised to get it back to me in a few hours. I’d never see the money again, but every time I’d see him I’d shake him down for something. I never let him forget it. We knew each other well enough so it was hard for me to punch him out, but — [laughs].

GROTH: He counted on that, right?

SPAIN: It’s funny, I guess, you know how junkies kind of size you up.

GROTH: I don’t have Zodiac Mindwarp, so I haven’t been able to read it. But when you said you brushed up during that period, I assume you mean you practiced a lot.

SPAIN: Yeah, I did a lot more drawing.

GROTH: What was your approach like? What were your influences? What were you inspired by?

SPAIN: Well, I was reading Marvel Comics, so that stuff had an influence on me. I was influenced by ... what was that guy’s name? There was a whole bunch of books by him. He was a German artist that was around the turn of the century, that was probably the best draughtsman in world history, who did all these great drawings of giants picking up huge clumps of people, or elephants skating ...

GROTH: Heinrich Klee?

SPAIN: Heinrich Klee, yeah. And I had always thought of myself as a hotshot. And when I saw what he was doing, the fact that he could sit down and without any pencil, draw a picture, I was trying to do that. And I wasn’t too successful at it. Eventually I got to the point where I could do that, but not as well as he could do it. But it was an interesting exercise in trying to conceptualize things. Because one part of drawing is the technical aspect of getting your drawing right. The other aspect is to be able to think up things. So that those attempts, though they were very frustrating and not immediately successful, helped me sharpen sharpen those conceptualization skills so that I I could try to form something in my mind. And even though putting it in pencil is really the easier way to go, it just sharpened my general drawing skills. It was an interesting and frustrating time, art-wise.

GROTH: Did you learn a lot of draughtsman skills at school?

SPAIN: I did learn some. I did learn some. The thing about Silvermine was it focused on abstract art, that was eventually helpful. But at the time, it didn’t seem to help me in what I wanted to aim for, which was learning those skills of good drawing that are necessary for comics. Ultimately, the way you learn to draw is by drawing a lot. You just can’t get around it, but all that other stuff, design and all that, is of course useful in comics, too. In one of our classes, you had a bunch of black rectangles that you had to arrange on a white page. And at the time it seemed pretty dumb. Why put it over here? What’s the difference if I put it over there? All that compositional stuff, you find out eventually, is important, too.

GROTH: So eventually it did help you?

SPAIN: Yes, it did. I had good teachers. I always had of an attitude, you know. I would go through periods when I thought I was a real hotshot, and other periods when I realized I wasn’t as hot as I thought I was. I would go back and forth. Interestingly enough, at the plant there were a lot of good art critics. If you drew a babe that was out of proportion here or there, guys could spot stuff, so ...

GROTH: After many careful years of studying Playboy ...

SPAIN: That’s right. The one boss that I was telling you about, who would get annoyed if I didn’t have a dirty picture for him, I remember him sitting at a desk, putting on his glasses and looking at some skin magazine and saying, ‘When you get to my age, this stuff doesn’t bother you at all.”

GROTH: Did you draw a lot from life?

SPAIN: I did some, but the thing about comics is, you had to be able to draw from your imagination. When I was in art school we did a bunch of life drawing. As a matter of fact, my first drawing class, we had to draw this concrete block on a table. That was pretty easy. I did the concrete block, I drew the details on it, I did the table, I did everybody sitting behind, then I drew the rafters up on top of it, and gave it to the guy and said, “Yeah, what next?” So I had this smart-aleck attitude ...

COMICS ASSIGNMENT

GROTH: Well now, Walter Bowart basically gave you an assignment to do a 25-page comic?

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: And this was apparently the first extensive strip you would have tackled?

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: So how did you go about approaching that, and how did you find the subject matter? Come to think of it, what was the subject matter?

SPAIN: I just started doing things that came to my head, which was ... let me see. I had The Heap in it, I made up a character called Phlegm Master who would shoot phlegm from a gun. I started off with Captain A-Head, which was a fat Captain America menacing a woman sitting in a deck chair on a roof. I just made it the up as I went along.

GROTH: Was it of a political nature?

SPAIN: Not really, no. I imagine you could probably get something political out of it, but ...

GROTH: But that’s not what you were thinking?

SPAIN: That’s not what I was thinking.

GROTH: And that ran in the East Village Other?

SPAIN: It was a separate publication of the East Village Other.

GROTH: Now, you drew that in Buffalo?

SPAIN: I did it in Buffalo, and I was down to a hundred bucks, and moved to New York City.

GROTH: Always good to move to New York with a hundred bucks in your pocket.

SPAIN: Yeah, right, and it was cold, and I would put cardboard over the holes in my boots. It was good when it was cold, because the ice would freeze over, and when the thaw would set and melt the ice, I’d be in trouble. A friend put me up, and ... I was able to get through.

GROTH: Did you actually move to New York for what you thought was good, or —?

SPAIN: Yeah, basically.

GROTH: What prompted you to do that?

SPAIN: Well, when I was first in New York, I had looked around for ways to make a living doing art, but I wasn’t too successful. I had approached Ed Sanders, and he gave me the brush-off, but something strange had happened because somehow in the intervening years, my stature had grown in Ed Sanders’ eyes. But when I brought Zodiac Mindwarp to New York, Bowart was less than enthusiastic about publishing it. And I had heard that Ed Sanders was thinking about publishing it. So I took it to Sanders, this sparked Walter’s enthusiasm and he ended up publishing it.

GROTH: Who is Ed Sanders?

SPAIN: Ed Sanders started the Fugs, had the Peace Eye Bookstore, wrote a book called Helter Skelter about Charles Manson, and was an important figure on the Lower East Side at that time.

GROTH: And so you moved to New York with the intent to do what?

SPAIN: Well ... to see what would happen next.

GROTH: Did you want to make it as an artist, or were you even thinking that far?

SPAIN: Yeah. I assumed that I’d probably end up in above-ground comics, because underground comics probably would last for a while and then fade out. But I started working for the East Village Other and was actually able to live on 15 bucks a week.

GROTH: Those were the days.

SPAIN: Those were the days. And at some point, I started getting other jobs, and also I was stoned all the time.

GROTH: That’s a pretty amazing feat on 15 dollars a week.

SPAIN: Yeah, right. So for some reason I pulled it off.

GROTH: You have to admire that fact.

SPAIN: Yeah, when I look back upon it, Buffalo’s a drowsy, provincial city compared to New York. So in Buffalo, when you walked down the street and somebody else is walking down the street, people give way for one another, and people actually spend all afternoon talking, and it’s a very relaxed atmosphere in Buffalo. I’d go to New York ... as soon as I would step off the bus, something would happen. And this frantic pace went on and on. One thing would happen after another. Years later I’d be leaving New York and the momentum would return to normal. But there was never a dull moment in New York. GROTH: Did you like that kind of energy?

SPAIN: Yeah. I like New York. New York is one of my favorite places.

GROTH: Did you still own a bike when you went to New York?

SPAIN: No. No.

GROTH: Because that would be almost impossible to.

SPAIN: Yeah, my life had changed even though the Road Vultures were still going, and I was still in contact with them. The Road Vultures came down to one of the anti-Pentagon demonstrations.

GROTH: At some point, I don’t know when it was exactly, you did work for the Gothic Blimp Works. Could you describe your social and cultural milieu in New York at that time, around ’67, ’68?

SPAIN: Yeah, it was really a great time. I met Kim Deitch ... in one of our adventures, we were going to see Art Spiegelman. His Topps Bubblegum Company was on Atlantic Avenue, or something like that, and we found an Atlantic Avenue that was in the Bronx, so we ended up in the Bronx.We were both assuming that we could mooch carfare either off Art or one another to get back. I had been there before and I knew that you just had to walk down the street a few blocks to get there. After the walking about ten blocks we knew we were in the wrong place. Some old guy who we asked told us that the only Topps Bubblegum Company he ever heard of was on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn and so me and Kim were a couple of broke hippies in the Bronx, trying to mooch 40 cents to get back, and people did not want to know nothing. It started to rain, we were quite a forlorn pair. Finally this nice girl gave us the money, but it was one of my few experiences with begging — it’s very demeaning to me. People were most unreceptive.

GROTH: So the indirect reason you had to panhandle was because of Art Spiegelman?

SPAIN: Indirectly. [Laughter.] Well, I knew the Lower East Side, but once you got out of Manhattan, I really had no idea where I was. So we finally got back to the East Village Other. It was a memorable time.

GROTH: So how did you come to meet Kim [Deitch]?

SPAIN: I met him through the East Village Other. And I ended up moving in with him. We had this place on Eighth and B — Eighth and C. The landlord was afraid to come in the building, so we stopped paying rent. So we had this place free for — I forgot what, it was like ... not quite a year, but there was this gang of Puerto Rican kids that kind of ruled the building. Kim had a pistol. But the chamber, the part you put the bullets in the revolver, wobbled around, so fortunately we never shot it. It would have probably exploded.

GROTH: The cylinder wobbled?

SPAIN: Yeah, the cylinder, yeah.

GROTH: Kim had a gun? [Surprised.]

SPAIN: Yeah, well, Kim used it to get up and down the stairs.We lived on the sixth floor. The kids in the gang would try to charge a quarter to get out the door. I wasn’t paying them nothing. When I was first there in ’65, I was friends with a whole bunch of Puerto Rican guys. Being Spanish, they looked out for me, and I got to know them. They didn’t like the hippies because they would rob from the bodegas so there was a certain amount of tension. When I got back there in ’67, there was even more tension between the Puerto Ricans and the hippies. And in this place where me and Kim were living, the older brother of one of the kids was the leader of the gang. At some point the apartment next to us burned down. And these guys would kick a hole in the wall but we really didn’t have anything for them to rob. They would rob my girlfriend’s panties. They probably suck-worshipped them or something. Anyway there were many adventures in that apartment.

Later on, a friend of mine from Buffalo came, and for some reason he broke down the door. And at one point we had a pound of grass in there, and we have this door propped up; there was much craziness. At one point I actually had something like $116. It was the first time I’d seen anything over a hundred bucks in years. I’d saved it up. And I was so happy, I was throwing it around. I stashed it somewhere, and later when I was going out the door, a kid tried to hit me up for the quarter toll to get out the door. I told him, “In lieu of a quarter, how about me allowing you to still have your teeth?” Then the kid mentioned something about a $116. I was stoned at the time, and it didn’t register until later that evening. I was at the movies with my girlfriend. Suddenly I woke up and I realized the kid said $116. How did he know? That was exacdy the amount of money I had, $116. I got out of the theater, went back, and stuck the money in my pocket, and later on when I came back, they had kicked a hole in the wall, and were looking for that $116, which they didn’t get. So it was just that kind of a scene. There were no cops. In Buffalo there was this law and order machine, so people would nervously smoke a joint behind locked doors. On the Lower East Side you would walk down the street and smoke a joint, and you didn’t have to worry about the police. But you did have to worry about the locals.

GROTH: This was in Manhattan?

SPAIN: This was in Manhattan on the Lower East Side, yeah. Alphabet City, they call it.

GROTH: Did you acclimate yourself to this new —

SPAIN: Yeah, actually I did pretty well.

GROTH: You were unfazed by it.

SPAIN: I was fazed, but at some point I realized that I was like a Puerto Rican, but bigger. I’ve been friends with Puerto Ricans, and I’ve been enemies of Puerto Ricans. I’d rather be friends with Puerto Ricans. Most of them are good people, but these kids were nasty. To show how out of it I was: I did a mural, I just did it with my finger on the wall. I had a bunch of paints. At some point I found a little black doll, it was a little black baby doll, and I wanted to put it up somewhere, because it was a neat item. I ended up nailing it to the wall. At one point in doing this mural I had some red paint left over, and I couldn’t think of what to do with it, so I finally put it around the nail. So there it was, I had this black baby doll nailed to the door ... not giving it much thought, I was stoned, and it was an objet d’art ... One time I tried to hit up on some Puerto Rican girl, and she just turned from me in disgust. But they didn’t mess with me, either. One time me and Crumb and Kim were walking up the stairs, and a guy steps in front of Crumb, a guy in a vermilion suit. Crumb had to walk around him. And I purposefully banged into him. The guy just shrunk back. And I never thought it at the time, but having this doll — they must have seen it when I opened the door, and they, being into all sorts of voodooistic ways of thinking, that must have been seen as an act of insane balls. If I had realized that that was what it was, I would have immediately taken the doll down. Being a stoned-out hippie, I just left it there.

THE NEW YORK SCENE

GROTH: From what I know of you and Kim, you seem very different, although I assume you have a lot of shared affinities. But Kim seems very reserved and quiet, whereas you seem much more confrontational, bellicose. Were you guys good roommates?

SPAIN: Yeah, we had a lot of good times, got along real good, and are still good friends. I haven’t seen him for a while, but if you run into him, tell him “Hi” for me. I enjoy his stuff in Zero Zero. And tell Mack White that I think his stuff is great, too.

GROTH: What was the social and artistic context like at that time? There were a lot of people who coalesced around East Village Other and Gothic Blimp Works. Crumb ... I think Bill Griffith was there at that time ...

SPAIN: Yeah, Spiegelman. I think Bernie Wrightson did some stuff.

GROTH: Vaughn Bode.

SPAIN: Vaughn Bode, yeah.

GROTH: Who did you hang out with? Did you hang out with all of them?

SPAIN: We hung out, yeah. I actually had a few buddies there. I had a difficult time being a flower child. That Flower Power thing had a hard time in general on the Lower East Side; it was a grimmer scene. Coming to California, which I did for the first time at the beginning of ’69, you could really see how nice it was out here, and how different it was from New York, and how people could feel that way, could feel all the posters, and Flower Power ... But the Lower East Side was a little different. You really had to watch your back on the Lower East Side.

GROTH: It’s my impression that Kim was deeply into comics then.

SPAIN: Oh yeah, we were both doing weekly strips, yeah.

GROTH: And of course, Kim’s dad was a cartoonist.

SPAIN: Yeah.

GROTH: Did you learn a lot being Kim’s roommate? Was it a learning experience as well as —

SPAIN: Well, I learned a lot working with the East Village Other. And I was able to get used to turning out a weekly strip, which is a big task when you first start doing it. It would probably be a big task now, even though I just finished doing Nightmare Alley, but ... knocking off a full page the way we did on a weekly basis is still a lot of work. Me and Kim’s style is different. What I learned from Kim was plotting out a story, and getting an interesting ending, and developing characters, and that sort of thing. It’s interesting working with artists who do one panel, they’re basically painters. But the task of doing a narrative story is a whole skill in itself, needless to say. So doing Zodiac Mindwarp, every day I would draw whatever came to mind, and at the end of six months I had 25 pages. Later, when I first started doing strips for the East Village Other, I used that same formula. Whatever would come to my head I would draw. At some point, I’d coalesced into Trashman, Agent of the Sixth International. I forgot just exactly when that happened, but I used to get up at about three o’clock in the afternoon and get to bed about maybe nine o’clock.

GROTH: In the morning.

SPAIN: In the morning, so you’d just have a lot of time when you’d be sitting around stoned, trying to think things up. Eventually all this stuff just sort of coalesced. I think that when I came out to San Francisco, and had the problem of doing an eight-page story or a five-page story or something like that, I think that my skills sharpened. I started doing a strip called Manning, which I, at that point, felt was better plotted out than the early Trashman. The early Trashman was basically something I would make up as I went along. I would just draw whatever came to my mind that week. At some point I popped an ending on it. But it’s really not a well-plotted-out story. Kind of hippie ... spaced-out, non sequitur ...

GROTH: Where did Manning appear?

SPAIN: Manning appeared in the East Village Other. I did that the year I came back, in ’69. That’s really when Gothic Blimp Works was going full bore, because underground comics really looked like they was gaining in popularity, and so besides doing a weekly strip in the East Village Other, part of our job was to put out the newspaper, and so we really worked hard there in that time, doing one thing and another.

GROTH: Were you able to make a living just doing underground comics?