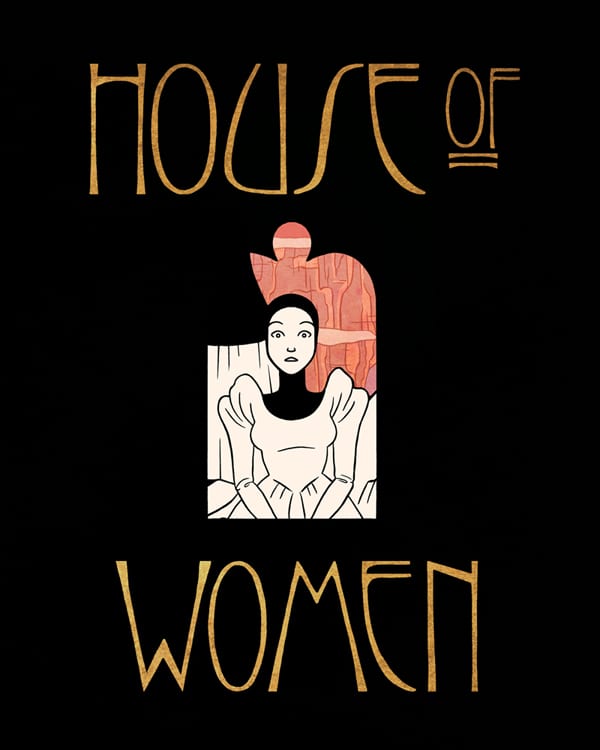

I first met Sophie Goldstein years ago at New England Webcomics Weekend in Massachusetts in 2009. At the time she was co-writing and drawing the webcomic Darwin Carmichael is Going to Hell. It was her first comics show and as she joked, it ruined her for what she would come to expect. In the years since Goldstein earned her masters degree at the Center for Cartoon Studies, completed a number of minicomics and short comics including “Girl Talk,” “Edna II” and Coyote.” Her comic “The Good Wife” was featured in Best American Comics 2013 and she won an Ignatz Award in 2014 for her minicomic “House of Women, Part I.”

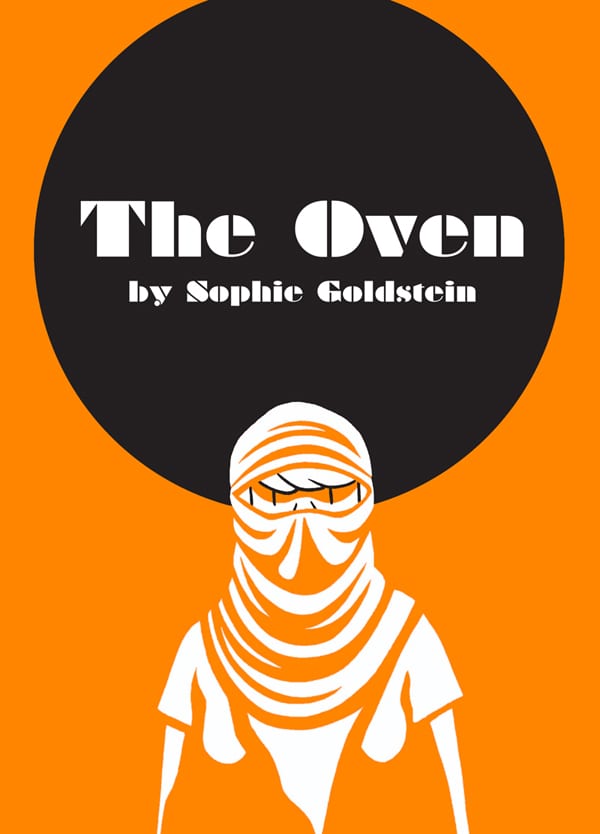

2015 is a busy year for Goldstein. She has stories in the upcoming anthologies Fable Comics (First Second) and New World (Iron Circus). She’s in the midst of finishing up “House of Women, Part 2” and co-writing a graphic novel with her Darwin Carmichael colleague Jenn Jordan. Last month AdHouse published Goldstein’s first graphic novel, The Oven, and we spoke about how her style has changed over the years, her time at CCS, color, and science fiction.

We’ve met but I don’t really much about you beyond the work. Tell me your origin story.

We’ve met but I don’t really much about you beyond the work. Tell me your origin story.

I grew up in Los Angeles, California—the land of perpetual sunshine. I applied early admission to NYU because I desperately wanted to live in New York, which at the time seemed like the center of the universe. At NYU I studied English Lit, graduated, and stayed in New York for a few years, working as an administrative assistant for a niche grad program. Then I got bored and moved to South Korea to teach English for a variety of reasons that seem pretty ridiculous now. A year later I came back to the states and applied to CCS.

Darwin Carmichael started in 2009. Where in the timeline was that?

I graduated from college in 2007 so it was a couple of years into my administrative assistant career. I think the majority of people who read webcomics are disaffected teenagers and bored office workers and I fell into the latter category. I started reading Jeph Jacques’ comic, Questionable Content, which is like the gateway drug of webcomics. Then I found comics like Octopus Pie–which was amazing and remains an amazing comic that I still love and really look up to. At one point I had at least fifty webcomics I was following.

While I was working for NYU I took two continuing education courses at SVA in comics. The first one was with Tom Hart and the second one was with Matt Madden. I had no idea how lucky I was—I just had no point of reference at that time. Then I started making autobio comics, y’know, as you do.

Then one day I was having lunch with Jenn Jordan and we started discussing the possible karmic costs of eating dead babies—and that lead to the premise for Darwin Carmichael—a world entirely ruled by karma where religious and mythological figures are commonplace and all seem to live in New York regardless of their country of origin. At the time it seemed like no big deal to commit to posting a webcomic twice a week for the foreseeable future. That’s how the comic got started—being bored and having free time, which are two things that very rarely occur anymore.

Had you been drawing a lot? Were you making comics prior to that?

I’d drawn my whole life. I made some attempts to draw personal comics in college, and I illustrated a 50-ish page comic on the 2004 election in Ohio that my mom wrote, called “Cheated!” that’s still available on amazon, last time I checked. My mom grew up in Ohio and was there for the election and the comic is a kind of lightly fictionalized on-the-ground report of the awful election-fraud that went on there. I drew the comic over the summer between my Sophomore and Junior year of college and during that time I lived in a trailer that was permanently parked behind my mom and step-dad’s house. Unbeknown to me or my mom the trailer had a termite infestation and every morning I would wake up lightly dusted with termite droppings. It was a great summer job.

It wasn’t until I took those SVA classes that I made my first minicomic. An autobio comic, of course, about my dad. It was very serious and involved a story about my paternal grandmother’s Alzheimer's, which I think it a bit of a cliché now. I also did several comics about my hot-sauce obsession, one of which involved anthropomorphized taste-buds. Those you can’t find online, thankfully.

I can see the influence of Questionable Content on Darwin Carmichael. Questionable Content has these science fiction elements and has a mixture of the fantastic and the mundane that you had in Darwin Carmichael.

I can see the influence of Questionable Content on Darwin Carmichael. Questionable Content has these science fiction elements and has a mixture of the fantastic and the mundane that you had in Darwin Carmichael.

There are lot of popular narratives where the protagonist enters a secret world that the larger world doesn’t know about—Harry Potter or Narnia or Jeremy Thatcher, Dragon Catcher, which I remember reading multiple times when I was a kid. But we liked the idea of having all these fantastical elements just be a part of our day to day existence to the point where they’re boring or mundane. I see a lot more examples of things like that in narratives now, but when we came up with the idea it seemed like something different.

That idea, taking fantastic or science fiction elements but using them to tell a more ordinary story of people’s lives, is a theme that runs through your work.

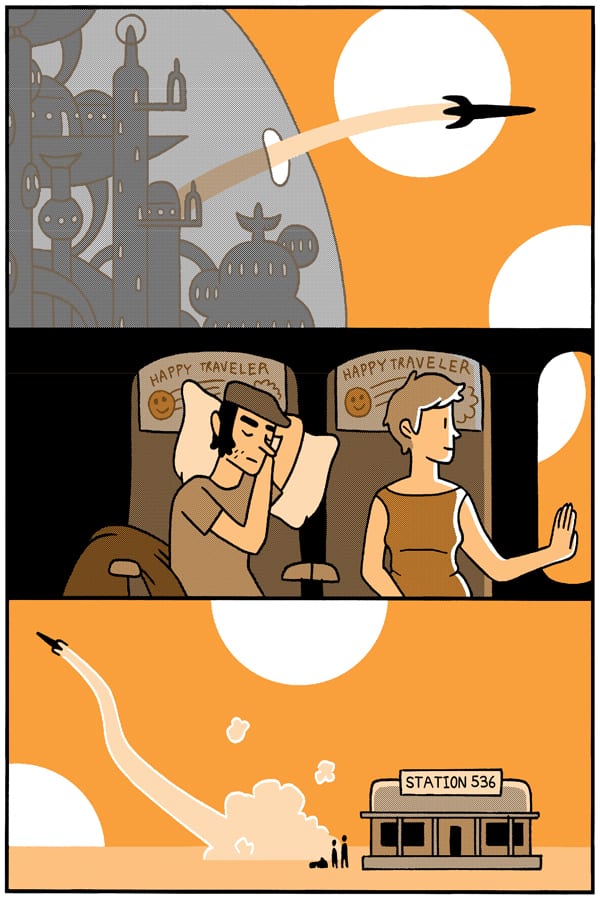

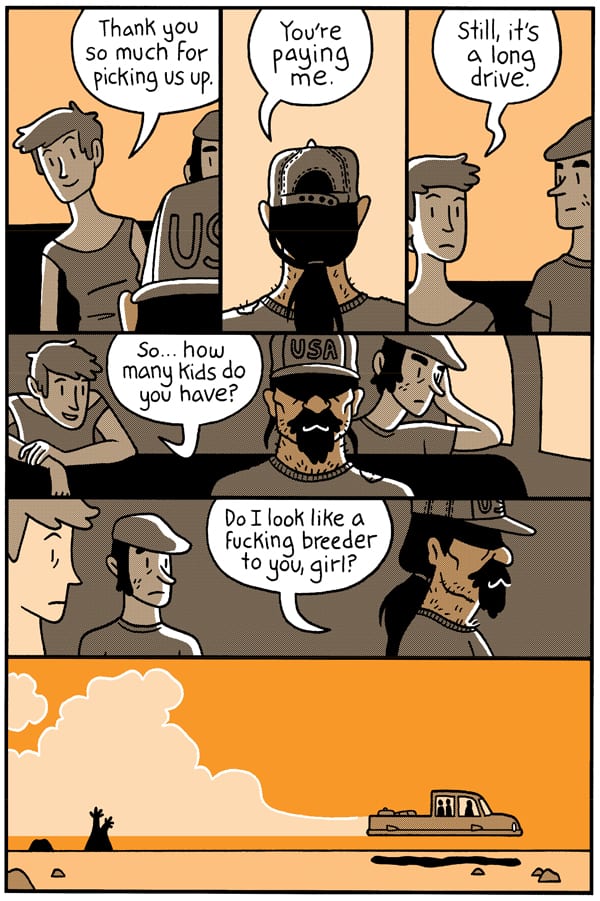

There’s hard sci-fi and then soft sci-fi—what’s usually called “speculative fiction”. Those are two very different approaches to dealing with the common tropes in science fiction. Hard sci-fi is more of an exploration of the future and technology and the mechanics of that whereas soft sci-fi or speculative fiction tends to use the elements of science fiction to explore more personal themes, or to explore the impact of technology on our relationships and psychology. That’s the thing that I find interesting. Creating an artificial environment for a story gives you the laser-like ability to focus on a specific issue, like gender or the ecological impact people have on the earth, without other distractions.

Also, as a reader and a writer I’m more interested in character than plot so that can necessarily limit the scope of a story. Perhaps if your book is 500 pages long you can cover an interplanetary war while also delving into the inner lives of your characters but The Oven is only 72 pages, so I had to make some choices.

In The Oven, I would argue that most of the story could have been set in the present and done in a realistic fashion with only a few changes.

It’s funny—I had the thumb-nailed script for the whole book and I asked Jason Lutes to take a look at it. He had some feedback and then he asked me, why is this science fiction at all? It doesn’t have to be. You could set this in the contemporary world.

I didn’t really have a good answer for that except that I like science fiction. It feels right to me. Once you set things in the real world you have limits—settings need to be accurate and plausible. I’m just not interested in that. I like to be able to make shit up.

For instance there’s a lot of drug use in the comic but instead of having the characters smoke pot or shoot heroin they’re eating these weird butterfly-like bugs. That, for me, was way more fun to draw and a much richer visual metaphor for the comic. I remember reading a Jason (the Norwegian cartoonist, not Lutes) comic where instead of having cars all the characters were peddling around on unicycles. For no real reason, he just didn’t want to draw cars, I assume. That’s just brilliant.

Why did you decide to study at CCS? When did you decide that comics are what you wanted to focus on?

I had heard about CCS a number of years before but the timing was never right for me to go. Then prior to moving to South Korea I was in this serious relationship that imploded and splattered all over my life after I returned.

So, it seemed like a good time to do something completely different.

I was getting serious about comics and serious about “Darwin Carmichael.” It’s not like you need to go to school to do comics, but I thought that I would get better a lot faster if I went to CCS and focused for two years—which was completely the case, I think. That’s what I wanted—and it was a great time to get out of New York.

Was the major benefit for you the chance to focus on your work or were there other direct benefits for you over those two years?

I was in a completely different framework than what I was in before. When I was doing “Darwin Carmichael” previously, I was pretty isolated. I wasn’t a part of any comics community. I had friends who read comics, but I only knew a couple cartoonists and my frame of reference was mostly webcomics.

Students sometimes refer to CCS as “Hogwarts for cartoonists.” You leave the muggle world and you’re in this crazy land of comics wizardry where you just live and breathe comics all day long. I got exposed to a lot of comics that I never would have read before. Also, because my classmates were so talented, I was more challenged than I had been. It’s not like you’re really competing at CCS, there aren’t even grades, but I’m a competitive person, so I was competing even if nobody else cared. [laughs]

I just wanted to be the best and trying to do that in a class full of talented people under the direction of Jason Lutes and Steve Bissette and Jon Chad and all these people who really know their stuff was just phenomenal. It’s really the environment. The classwork is great, but you could do that in an online course.

Doing comics that intensely for two years was great, but I needed to have a more well-rounded life than what a lot of grad students have. For two years I was running a race, but really life is a marathon, and I couldn’t keep up the same pace. Leaving White River Junction helped me figure that out and find a balance that’s sustainable and not exhausting and constantly stressful.

You graduated from CCS in 2013, which is also when you ended “Darwin Carmichael.” Were those two things related?

I loved “Darwin Carmichael” and I enjoyed doing it, but I wanted to do other stuff without the weekly commitment to a web comic. It’s hard for me to constantly switch gears between projects in the way I would have had to do to keep “Darwin Carmichael” up and running. Also, if you look at some long-running webcomics you can see that some people lose heart but they keep doing it because it’s their baby or their cash cow or they just feel afraid to move on—I don’t know. I didn’t want that. I wanted “Darwin Carmichael” be a story with an ending and happily Jenn felt the same way.

It’s not the end of my partnership with Jenn, though. We’re writing a graphic novel together right now. Unlike “Darwin Carmichael,” where we were making it up storyline by storyline, we want this to be complete and structured before I begin drawing it.

I ask in part because reading a lot of the comics you’ve done while you were in school and in the years since, there is a noticeable shift in style and approach. Is there a reason for this? Were you conscious of this?

I don’t think I made a conscious decision to change my style. It just happened over time. That’s just the tendency when you draw enough. With regards to “House of Women,” I made some very conscious stylistic decisions, so it looks differently from a lot of my other books. It was inked with a brush and I was looking at a lot of art nouveau artists, particularly Aubrey Beardsley, and classic Japanese artists like Hokusai for inspiration. In general though I just try and do the best I can and hope my art improves from project to project.

There are a few cartoonists who continually change up their style and do a lot of visual experimentation and I really admire that, but I’ve had to make peace with myself and realize I’m just not that kind of cartoonist. I’m more of a writer then I am an artist, at heart.

I look at “House of Women” and “The Oven” and you’re using a limited color palate, a simpler style, and I don’t think you’re trying to make it look and feel different from say, “Darwin Carmichael,” but you are making many different choices.

“The Oven” was originally serialized in Maple Key Comics, which is an anthology that my classmate Joyana McDiarmid published. The anthology was six volumes with an volume out every two months. I decided to make it twelve pages per chapter because that seemed reasonable—even if I had other projects I could always do 12 pages every two months. I made some choices that I thought would make drawing it even faster, like the little slot eyes. In actuality I don’t think it helped at all because I spent all this time erasing and moving them a micro-fraction to the right or left. I don’t know. It was a very silly thing.

The limited color palate was a printing limitation. I wanted to do something special for the AdHouse edition. I talked with Chris Pitzer and he agreed to two color production so it would be black and a Pantone color. The coloring in the book is a mixture of a certain percentage of the orange Pantone color mixed with black. That created the palette of eleven colors plus black and white. Then for printing I just did the black separation as a half tone and the Pantone separation as a solid. I got the idea from Joe Lambert’s “I Will Bite You” book.

I’m far from the first to make the observation that limitations can really help creativity but it was definitely true in this case.

So it was printed in black and white for “Maple Key?”

So it was printed in black and white for “Maple Key?”

It was black and white with a single gray tone—which ended up being really useful when I went to color it. I ended up still using a lot of the shapes that I made in the gray scale as a guideline and just dropping in the colors. That ended up being a pretty useful exercise.

It was amazingly fast coloring process compared to what I had done before. When I was doing “Darwin Carmichael,” the idea of limiting my palette had just not occurred to me. I was using every color and coloring would take forever because I had to make a million decisions. AND I was doing it all in RGB. If I only knew then what I know now.

On the back of “The Oven,” you have a lovely pull quote from Eleanor Davis. She works in a similar way to you, using fantastic elements to get at something about how we live and think.

Eleanor was my thesis advisor at CCS! Seniors get to pick a thesis advisor in their senior year and Eleanor was my first choice since I’d been a fan of her work for such a long time and felt a lot of kinship with her.

She’s a very elegant cartoonist. Her work is much more lyrical and poetic than mine tends to be—if I could flatter myself to even make a comparison. I think part of that is that her visual style is very personal and very textural. The first thing I ever read of hers was in Mome, this wonderful story about this man playing his lute in the woods and attracting the attention of this antlered forest woman. He draws her in and seduces her, but the only way he can keep her is by constantly playing this instrument. That’s where the story ends. It has this wonderful feeling to it without being explanatory or too on the nose. Eleanor is just so great at exploring complicated emotions in her comics. Her book How To Be Happy was just one of the best things I’ve read in years.

Is that something you’ve been very conscious of where it’s not that you’re not explaining the world, but you’re often telling the kind of story and telling it in a certain way that little has to be explained to get at the heart of the story.

Is that something you’ve been very conscious of where it’s not that you’re not explaining the world, but you’re often telling the kind of story and telling it in a certain way that little has to be explained to get at the heart of the story.

Absolutely. I think that you have to trust your reader. As a reader you want the experience of making connections on your own—that makes you feel more inside the story than if someone’s like, this is what this mean and let me explain this bit of technology to you.

You have to figure out what’s realistic for characters to talk about in a world where they already understand the rules and technology. I think that’s why you have a lot of fish out of water stories where everyone is explaining things to a character who’s essentially a lens into the world for the reader.

I think it’s better to let go of a commitment to having readers understand everything—even if it means you’re going to have misfires and have readers who will miss what you’re trying to do. I’ve had that happen. It can be frustrating and sometimes upsetting, but that’s a sacrifice I’m willing to make because I think the people who do get what I’m trying to say enjoy it more for me not explaining everything.

I assume that you’re working on “House of Women, Part II”–if for no other reason you won an Ignatz for the first part. Do you have an ending for it in mind?

It was all planned out, more or less, when I started it. It’s going to be two parts so I’m finishing the book now. Most of it’s thumbnailed except for the very end. Ending’s are hard, man.

I feel like there’s a lot more pressure on me for Part II than for Part I, obviously.

You mentioned before that you and Jenn are also writing a graphic novel.

Yeah, those are the two major things that I’m working on right now. Hopefully “House of Women, Part II” is going to be done for SPX and then I’ll be able to focus more on that project. I have some freelance work lined up as well.

It’s theoretically possible for me to do a lot more than I’m doing right now but I don’t think it’s possible for me to do more and be happy. I’m trying to take the long view of it and not feel like I have to have a new minicomic for every single show. Also I’m so tired of binding minicomics. Every time I finish making a run, I’m like, I’m never doing this again, and a couple months later I’m back to binding more of them. But it’s worth it, man. I don’t like screen printing, so I do die cuts. People like those die cuts.

You’re doing a lot of events this summer. Are you doing most of them to promote the book?

A lot of it is to promote “The Oven”, for sure. I have three bookstore appearances and then a number of conventions, including CAKE, Heroes, Space and SPX. Some of them where I’ll be tabling with AdHouse and others where I’ll be on my own. It’s psychologically hard to take the time to promote because it doesn’t always feel productive or like “real work”, but it’s essential to having a sustainable career. I also added a bunch of cons to the schedule because we did a Kickstarter for the “Darwin Carmichael” book and my main way of distributing it is to sell it at conventions.

You do have books to sell, though, even if they do take up a lot of space.

I am very rich in book equity. [laughs]

The nice thing about doing a Kickstarter is once you cover your printing costs, every book you sell is pure profit. On a 25 dollar book, that’s significant. Whereas I don’t think anybody can really make a living selling three-dollar minicomics. The point where I started making money at conventions is when I started having books on my table. That’s made a lot of difference. It is hard, but there are a lot of options. It’s not like there’s one way of being an artist or a cartoonist. There’s a lot of different tracks you can take.

I try to take a more positive view of things. There are people who still pay well but it takes time to build the right connections. I’m still working on it. There’s a lot that you can do to lower your overhead, though. Making your style of living affordable is a big factor. Moving to Pittsburgh made a big difference. If I was still living in New York, I would have to have a full time job. This is the math that I do for my life—finding a way to live inexpensively so I have artistic freedom.

Is Pittsburgh a good comics town?

I think so. There are a few established cartoonists here like Ed Piskor, Frank Santoro and Jim Rugg as well as a bunch of up-and-comers. Frank is interested in building community which is very important. He and Juan Fernández put together this comic salon that meets once a month in the coffee shop below Copacetic Comics. Of course I haven’t attended for months because of other commitments—but it’s there.

I moved to Pittsburgh with a number of other CCS grads. It’s affordable. It’s a city with a lot of cultural offerings. The housing costs are much lower but Pittsburgh still has the infrastructure of a larger city. That’s magic.