A great webcartoonist once told me that the way to survive on the Internet is to build a cult of personality around yourself. You can see that strategy at work with most successful webcartoonists, who develop big online personalities (often much bigger and brasher than their meat-world personalities, as anyone who’s met Scott Kurtz can attest) so that bored and fickle websurfers have no choice but to pay attention to them. Visit the site of a big-name comic like Penny Arcade, and chances are you won’t even see the comic; it’s available via a tiny link in the corner, past blog posts and forums and advertising testimonials and status updates and everything else that goes into an online social hub.

And then there’s Tatsuya Ishida, who has, since January of 2000, been drawing his daily strip Sinfest without making a peep about it, patiently collecting readers and honing his craft. Save for a handful of hiatuses around 2006, the strip has updated seven days a week without fail for the past twelve years. Ishida seldom posts anything on the Internet other than Sinfest; he avoids online fora, grants few interviews, and limits his text communications to occasional, mostly tongue-in-cheek blog posts that stopped in 2007. Beyond his handful of other credits—he inked G.I. Joe and Godzilla comics in the 1990s—next to nothing is known about his non-Sinfest life. As he explained to Publishers Weekly in 2011, “less socializing means I can concentrate more on the strip.”

And it’s paid off, at least as far as Ishida’s skill as a cartoonist is concerned. Way back in 2000, he was already one of the few webcartoonists who could actually draw. But over the years his initially hit-and-miss storytelling has advanced by leaps and bounds, and the world of Sinfest has expanded into an absorbing pocket universe. It’s also earned him the respect of people who know what’s what in comics. Dark Horse started publishing Sinfest in print in 2009, cancelled the series due to low sales, only to start up again in 2011 because it’s just too good not to print.

Sinfest nominally revolves around Slick, a self-proclaimed pimp and player who looks like an evil version of Bill Watterson’s Calvin (over the years Ishida has gradually changed his character design to downplay the resemblance), and Monique, a sexy coffeehouse poet. It says something about the tenor of early Sinfest that Slick first appears selling his soul to the Devil (at a roadside stand that owes a debt to Lucy’s psychiatric booth) and Monique spends one of her earliest strips in a bikini, showing her ass to the reader at Slick’s command. But the characters have their sweet sides, and one of the engaging features of the early Sinfest strips is how, despite Slick’s obnoxious efforts to get into Monique’s baggy pants and Monique’s frequent disgust at same, the two are basically friends.

But the strip’s central characters often get shoved to the sidelines—Slick, especially, has felt increasingly irrelevant—and Sinfest is always, first and foremost, about what Ishida wants to cartoon at any given moment. For fans, the eclecticism is part of the fun. Raunchy strips about strippers are followed by cute cat-and-dog gags are followed by religious humor are followed by autobio strips are followed by shit-stirring political cartoons are followed by spoken-word poetry are followed by lessons in drawing Japanese kanji, one of Sinfest’s signature running features. Even in recent years, as the strip has developed a large cast and running storylines, Ishida still regularly breaks for one-off strips about whatever.

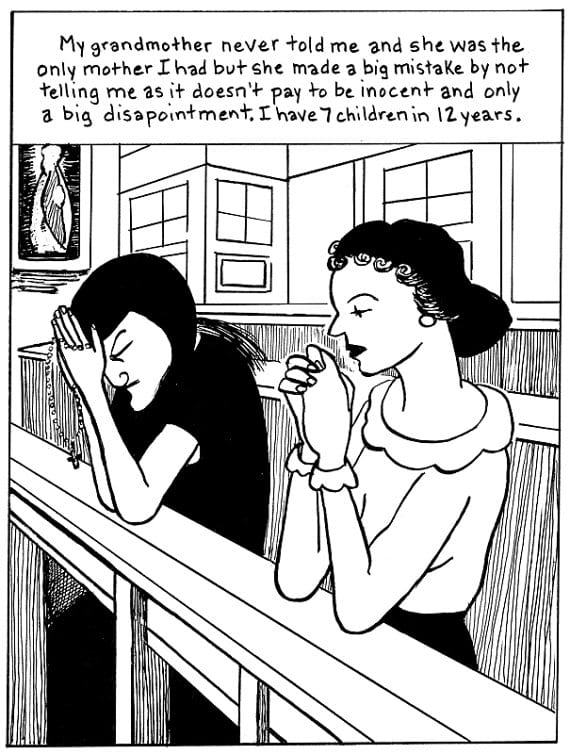

All of this is drawn in a rounded, think-lined, chibi-fied style that draws in roughly equal measure from Japanese manga and American newspaper strips. Ishida did a lot of comic-strip parodies early in Sinfest, always mimicking the original artists’ styles eerily well, and more recently (in 2010) drew a week-long storyline, “Lost”, in which his character Squigley the pig meets the casts of Pogo, The Far Side, My Neighbor Totoro, and other comics and cartoons; it’s clear he’s studied at the feet of the masters. There’s no question that Sinfest has gotten away with a lot of offensive material over the years, including racial caricatures, sex and drug humor, and lots of sexism, because it’s so darn cute. Ishida’s brush is clean and expressive, his characters delightful to look at. He even draws great backgrounds, and how many webcartoonists bother to do that? In 2006 he started doing color Sunday strips, and his color work has grown subtle and assured, but the black-and-white dailies look just as good.

Over time, the strip’s jokes about organized religion—the Devil and God, or at least His hand-puppets, have been regular characters from the beginning—have evolved into an ongoing plot with a cast of angels, demons, deities, and an entire subspecies of Devil People, a plot that’s deepened the personalities of all the recurring characters. One of the most popular recent storylines involves the romance between Fuchsia the devil girl and shy, bookish mortal Criminy, a relationship that ultimately inspires Fuchsia to abandon the Devil and cause various problems in the corporate headquarters of Hell.

Also recently, in a surprising twist given the strip’s early fondness for jiggly pimps-n-hoes humor, feminism has invaded the world of Sinfest. This development takes the form of the Sisterhood, an alliance led by a little girl in sunglasses riding a high-octane Big Wheel. With their power to open people’s eyes to the Patriarchy, which appears as a Matrix-like grid of sexist ideas floating in the air, the Sisterhood has raised the consciousness of various female characters. Feminist awakening takes different forms for different characters; Monique gets a butch haircut and stops using sex appeal to sell her poetry, only to experience backlash from her fans (including a tiny fangirl who worships Monique’s hoochie incarnation), while Fuchsia is inspired to abandon Hell for true love. Even Slick gets a glimpse of the patriarchal matrix and starts feeling uncomfortable about his own grabass behavior, although he eventually rallies.

Does the feminist plotline suggest that Ishida himself has mixed feelings about the politically-incorrect humor in his older strips? A recent stand-alone strip shows Ishida’s avatar cheering Jeremy Lin on TV and declaring, “I too must represent my people with dignity and class!” Cut to Ishida’s tiny fanboy (Monique isn’t the only character with impressionable young fans) yukking it up over a Sinfest collection full of “pimp ninjas and geisha sluts.” Unlike Ishida the cartoon character, Ishida the cartoonist isn’t about to share his feelings, except through his comic, and thank goodness for that.

The ongoing plots, even at their most complex, are expressed in minimal dialogue, Ishida trusting his readers to tease meaning out the characters’ allusive adventures. He’s as unafraid to be cryptic and subtle as he is to be outlandishly raunchy. In a field dominated by stick figures, sprites, and talking heads, it feels good to read a webstrip that lets the art carry the story.

The ongoing storylines started developing about two years ago, ten years into the strip’s run, and have transformed Sinfest from an attractive diversion to a must-read. Since Ishida knows his comics history, he’s probably aware that E.C. Segar drew Thimble Theatre for ten years before hitting upon Popeye, and that Alley Oop ran for ten years before developing the time-travel angle for which it’s remembered, assuming that Alley Oop is remembered. In the aforementioned Publishers Weekly interview, Ishida is quoted as saying, “I plan to draw Sinfest till I physically can’t. Like Charles Schulz did with Peanuts.” For some cartoonists, the ones who keep their heads down and draw like nothing else matters, because nothing else really does, the best is always yet to come.

Addendum: In the coming months, I plan to launch a new feature in this column, Webcomics Capsule Reviews. If you send a link to your webcomic to TCJ, I will add it to my review queue. I will be cruel and fair. If you don't want this fate to befall your webcomic, don't send it to TCJ.