Sammy Harkham is one of the most vital and influential figures in comics of the last fifteen years. When the fourth issue of his anthology, Kramer's Ergot, came out in 2003, it introduced the wider world of unsuspecting readers to a burgeoning quasi-underground scene of exciting young artists (Mat Brinkman, C.F., Geneviève Castrée, Leif Goldberg, Anders Nilsen, Harkham himself, etc.) and seemed to herald a new era in comics, one entirely free from previous models of serious comics, which had always seemed in one way or another shackled to the medium's long and tacky past. Succeeding issues of Kramers maintained and strengthened the anthology's reputation, and turned the title into the most editorially consistent and consequential ongoing comics anthology since Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly's Raw. A new issue of Kramers may no longer deliver the shock of the new, but to readers who have come to trust Harkham's editorial intelligence, integrity, and restlessness, it is still an event.

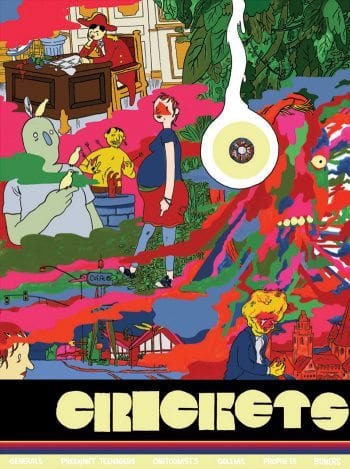

Even without Kramer's, Harkham's work as a cartoonist would mark him as a major talent. From The Poor Sailor (published in KE4) on, his stories have combined carefully observed moments of subtle realism and an almost classical sense of comics language, all set against an overriding atmosphere of hostility and horror. To indulge in reviewer's reductionism, it's as if Roy Crane were illustrating a story by Raymond Carver, in a project overseen by David Lynch in a darker mood. Most of Harkham's work has been gathered in the no-longer-appropriately titled Everything Together, and much of the rest appears in his ongoing solo anthology, Crickets. For the last four issues, Crickets has been the home of Harkham's most ambitious and accomplished story to day, The Blood of the Virgin, a bitingly funny yet melancholy serialized portrait of Los Angeles in the early 1970s, told from the viewpoint of an aspiring movie director (and failing father and husband) working for a Roger Corman-esque film company. The story is an ideal outlet for Harkham's strengths and interests: the depiction of setting, artistic struggle, and the human capacity for self-deception.

Most of this interview took place via Skype around a year ago, revolving around the then-impending release of Crickets 5 and Kramer's Ergot 9 (a sixth issue of Crickets is newly available), with a short update via email. The conversation has been condensed and slightly revised.

GETTING STARTED

Sammy Harkham: How does this work? You're calling me through Skype?

Tim Hodler: Yeah.

That's cool.

That way I can just record it.

That's amazing.

Yeah, I guess so.

I guess so. [laughs] Right. I remember having the zine back in the '90s and tape recorders and transcribing and turning over the tape and forgetting to turn over the tape. All that stuff.

I forgot that you did that. How long did you do that zine?

We—me and my friend David Kramer—worked on one for like three years. We were accruing all this material, but you're stoned all the time and you're dumb. You know, you're young and you don't know how to do anything. I interviewed Will Oldham. That's how I met him, when I was fifteen. And when I sent him the finished zine, he asked me to do art for the first Bonnie Prince Billy record. I don't know if you know his work or his music?

Yeah, yeah.

I'm trying to think who else? A lot of local Australian bands. How many were there? I think like two or three issues.

This was when you were in high school.

This was when I was in high school, yeah.

Do you still have any copies?

No. When I think back on that I forget that there was a whole part of my life when I was in high school and I was really serious about trying to make fanzines. I was getting work drawing posters for all-ages shows. I think back on it with awe a little bit. I got stuff done and it was good for me to have to turn in artwork and have people criticize it. And do everything wrong. You know, all the things that you do when you're starting out.

That's kind of a traditional underground cartoonist thing to do when you're starting out, too.

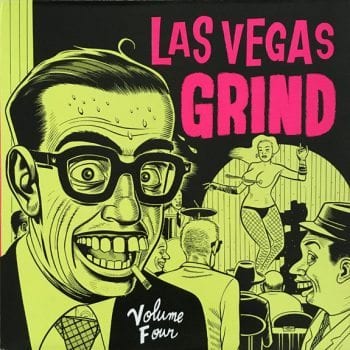

You're right. I think it's just that people want to draw. It's not necessarily that they feel an affinity to a scene but it can be where you discover comics. I think the first Clowes thing I probably ever saw was the cover to a record, Las Vegas Grind?

You're right. I think it's just that people want to draw. It's not necessarily that they feel an affinity to a scene but it can be where you discover comics. I think the first Clowes thing I probably ever saw was the cover to a record, Las Vegas Grind?

Sure.

Great cover. And you know, when you would see copies of Hate being sold at a record store, it put it in a context that made it feel relevant. Which if you're me, you're fading out of superheroes in '93, '94, and there was this whole world of comics that were cool. I think Fantagraphics was publishing Your Flesh. Do you remember Your Flesh?

I read a few issues, but not many. It was like a rock magazine or their version of it.

Right. And there'd be articles on William Burroughs and Harry Crews.

Very '90s.

[Laughs] It's true. What from that period has aged really well? I mean, we know which comics have. Any magazines of the '90s?

I don't know. There's some stuff I liked back then that I'm sure I'd think was terrible if I revisited it now, like Film Threat? I loved Film Threat.

I've been meaning to pull out Film Threat.

I thought it was great then. I don't think I would think so now.`

It's interesting. It makes you realize that things that are necessary while they're there, and it's kind of like that's it. And it's fine. It doesn't negate the worth of Film Threat, in my mind, if it is absolutely terrible, because it was exciting at that time. Gosh.

THE KRAMER'S ERA

That's funny. Since you and Dan are good friends, I asked him if there were any questions he thought I should ask you.

Oh, Dan. [laughs]

I don't think it matters! I never thought in terms of it mattering. so it has never mattered in a large sense. It's only in hindsight that I get a sense that it had any sort of impact, and I can’t do anything with that knowledge. It mattering to people isn’t a reason to do something or not do something. Continuing with Kramers is solely based on my enthusiasm, not others'. If it means something to some people, that's cool but that's outside my experience. Sometimes I think people got excited about Kramers because there was, and remains, so little to get excited about. You should answer this question, not me. You could tell me what you think.

What do I think? I think it matters, but I'm one person who has my tastes. I don't know if it's relevant. I hardly ever even talk to people about comics anymore. Besides...

Yeah, I never get the sense that anybody reads anything, or that anything that's in the past is ever re-read. The truth is that when I read a comic and I love it, I think, did anyone read this? I hope so. I get hung up on that-I hate the idea of good work being ignored. You and I are connected in that we work in the industry, but we're not on Facebook discussing new work.

No, I don't discuss anything on Facebook. I have a page that I never go on. But the thing I was saying before was that...

[laughs] We can keep talking about Facebook pages if you want, that's okay.

I really have exhausted my opinions about them. [Harkham laughs] But you are saying there's nothing around to get excited about in comics...

There's not a lot of great books, so we get excited about interesting books. By the time Kramer's 4 came out [2003], Mat Brinkman had a solo book, Marc Bell had a solo book, C.F. had been doing minis. To me, it didn't feel like I was showing anything new. I think the only thing it had going for it was that it was in color. A lot of those artists had not been published in offset and so that was the edge the book had. I did think that the majority of people who were going to buy it were familiar with those artists. I don't know if Teratoid Heights was out, but it was definitely around that year. And when you look at it now, you can see it's a very Highwater-inspired book, you know, so it felt very different. Think about that time. You had done The Ganzfeld and you were familiar with all those artists. I'm sure Dan was. I think I heard from Renée French at the time that he was talking shit about it. I know what that is, because I'm very ambitious, and Dan's very ambitious, and it's a little bit like jealousy and it's a little bit threatening, and it's a little close. It's what Kevin [Huizenga] calls a near-enemy. I mean the Venn diagram of Dan's interests and mine are very deep. He's just got a little more Alex Raymond in him. [Hodler laughs]

It wouldn't shock me if that is true, but I don't remember.

No, it's fine, because I understand it. It's so close. Same thing with [Tom] Devlin. Devlin saw Kramer's 4—and he was such a snide prick to me all through my teen years, just as a customer at shows, and he's such a prick in general—but he wrote me a nice email after that book came out saying this really nicely encapsulates what's happening. But to go back to the main point it felt like all those people were out there doing their thing.

I think that if you were really in the know, you would know some or most of those artists, but Kramer's gathered all of them together for maximum impact. So that if someone picked it up who was just curious, a whole new world would be open to them that they hadn't seen before. I think that's why it made such a big impact.

There's also the accumulative effect. The lesser strips fall away and individual pieces fall away because it becomes this whole thing. Everyone picks everyone else up with a book like that.

You said that was a good issue. Were there any issues of Kramer's that in hindsight you aren't as happy about?

Just this last summer I was in Minneapolis for this French/American drawing club thing. and in the work room there was a table of everyone’s books so we could get familiar with each other and a copy of Kramers 7, the big one, was there. I don't think I'd looked at that book since I sent in the files. Looking at that again was interesting because of how fucking dumb some of my decisions were. Some of it worked very well. When I picked that up, I thought, ah, if I'd cut twenty pages, and I was a much more hands-on editor, I think it would have made it a better book.

Are there any bad decisions you feel okay sharing?

What comes to mind are simple things, like artists not using the dimensions of the book properly, and I should have just asked them to re-letter their titles to fill the empty space better. Little things like that would have helped a lot, since each page really mattered.

Was that because that was an issue where you were working with a lot of very established artists?

Not at all. I think it's feeling timid. Asking people to make changes or being anything more than a cheerleader is difficult, or was for me at the time. After Kramers 7, I realized that I wanted to spend most of my time doing my own work. I enjoy doing Kramers but if I'm going to do it, I should make the stories as good as possible. And then I realized that there's a certain amount of mutual respect between me and the contributors. I'm not asking them to contribute if I don't already think they're great, so surely I can tell them, thanks for the story but I think you should tweak this. I think most artists are open to that and so the new issue has a lot of editorial input.

Is that just revision or are you requesting the actual themes of the stories?

Mostly revisions. Some artists if they ask about a theme or a direction and I would talk generally about what I am looking for. I have certain things I'm interested in reading. I always tell everybody [I'm looking for] a strong narrative. Of course, that means different things to different people. Also, treat the visuals seriously. Because the page is fairly large. It's almost 9 by 12, so it's a good size for reading as well as looking. You want the pages to be very visually dynamic. It doesn't have to be showy, but you want it to be strong, so that when you flip through the pages, it's really something. And then narratively that conversation is a little different. I will tell some people, you know, why don't you do a wordless story? Especially when I've been working on the book for a while, and I can see what the book needs and there are artist friends of mine who I can push around [Hodler laughs] and say, I need this kind of story right here. And often, they come through. But when I look through previous issues, that’s something that pops out at me, that I could have brought a more critical eye to the work and the artists would have been receptive to more editorial input. There was no need to keep my concerns to myself.

How old were you when you did Kramer's Ergot 1?

I was 18.

Was that the first time your comics were published?

Yeah. I think I've told this story before, but there were those ads in the Journal for co-op publishing. You could print 500 copies, or a thousand copies, and they would tell you you have this option for paper stock, you have this option for interior, two options for covers, and it was really cheap. It was like 500 bucks, 700. So I did it that way. And that was a good experience, because the book comes out and it was mortifying. It's so bad. Like paralyzingly bad. I mean everything is kind of like this, you finish a project and you think, I have to make something now to make up for this. [Hodler laughs] That's what every project often is. You're trying to course correct from the last thing.

What made you want to edit an anthology, rather than just publishing your own comics, or submitting to other publishers?

Well at the time, it felt impossible to get published and I didn’t have the patience to wait for that to happen. And I felt by including other people it could only be stronger, a power in numbers sort of thing. I was going to end the anthology after issue 3 but it was right around that time that I started discovering so much great self published stuff, probably because I was now going to conventions to sell Kramer's and meeting more and more people. And with the exception of Highwater, most of them were not being published. It felt like a gap there. And around the same time, Paul Hornschemeier was working for a printer in Canada and he really sold me on the idea of doing a color book, that that was a possible thing. All of that accumulated into issue 4.

FAMILY LIFE

I was looking through old interviews with you about your background and I found the basic outline of your career, but it was kind of surprising how little is actually out there, at least that I could find quickly, about your personal life. I know you moved to Australia when you were a teenager—

Uh-huh.

But that's about it! [Harkham laughs] And that you live in Los Angeles.

What else is needed?

I don't know.

He moved to Australia. That's it. That's the bio.

I don't know. I know that Dan Clowes used to march around to John Philip Sousa records and his mother was a mechanic, and Chris Ware was extremely close to his grandparents...

Right.

And Robert Crumb, we know everything there is to know about him. Do you have siblings?

I have five siblings. I have four brothers and a sister and I'm in the middle. I have two older brothers, but the next one above me is five years apart, so I'm the oldest of the four that came after the initial two. So it's kind of like the weird thing of being the middle child but there are elements of being the oldest, too. Because until you're about 25, that five years is a huge gap. I got a lot from my older brothers, but they didn't feel like my peers in any way. My brother just below me felt like a peer.

Because they were never in the same school, probably.

One was, but he was always way above, where it didn't matter. And all his friends scared me, and I was picked on [laughs] because I was so stupid. I still think I am very slow to learn anything. Once I learn something, I'm okay, but it takes me so long to learn anything. I think of how my brother would— I was such a dumb— My memory is that every day my brother would take off his sneakers, after having them on for fifteen hours, and he would say, "My socks smell like strawberries." And every day, I would sniff them. Every day. [Hodler laughs] Isn't that crazy? That is mean. I never did that to my siblings. And my older brothers told me that the world could end at any moment—that there was a button on the presidents desk that would launch an atomic bomb. So I lay in bed each night thanking God for not destroying the world yet. But yeah, there were six of us in the house. My oldest brother was into comics, and really into music and underground movies. Both of my brothers were really into movies, and that was the mid to late '80s, so that was the age when everyone was recording every movie that they would rent for some reason.

VCRs.

Yeah, when I think of that time, VCRs are a huge part of my childhood. But I got exposed to a lot of good stuff because of my two brothers.

HORROR

What was the first horror movie that made a big impression on you?

Probably Toxic Avenger or The Omen. I was watching the The Omen with my brothers and they made me turn my head at a certain grisly part. It was Omen II. I haven't seen the movie since, but I know there was something with an elevator or an elevator shaft and somebody gets stuck. And they forced me to look away. And then you hear the sound of something happening, and even at that age, whatever you visualize will be worse than what’s on screen. Have you seen The Toxic Avenger?

Close your eyes to replicate a young Sammy Harkham's experience with this scene from Damien: Omen II.

Yeah. It's been probably 15 years, but I've seen it.

I saw it as a kid, and it traumatized me. Years later at CalArts they were playing it in the lunchroom and at first I was appalled, like, how can they play it in the lunchroom? This is fucked up! But then you watch it, and it is so obviously just ridiculous. It's a parody of a horror movie. There's a scene where he runs over a kid with a bike and then reverses and runs over the kid's head [Hodler laughs] -- do you remember that scene?

No. It's been a while.

A group of teenage maniacs are driving around and they see a kid. It's night time, it's pitch black, and the kid's out for a bike ride. his sister has just told him to wear his helmet, its all very sweet. Then they cut to these evil teenagers maniacally laughing drinking beer and making out cruising around. They see this kid, they hit him with their car, and they're laughing hysterically. And then they reverse and run over his head as he's crawling to the sidewalk, and then they stamp their car with another kill logo like they've hit a person. I think the other logo is an old lady with a walker. Another one's a baby carriage, and the new one is like a little icon of a guy on a bike. As a kid I just thought that was real.

My mom grew up on a farm in New Zealand. My dad was born in Baghdad, moved to Israel as a refugee, and ended up in Australia as a teenager. He didn't finish elementary school. They're just working people. They weren't keeping track of any of this stuff. They don't know what's going on downstairs in the basement. I think that stuff definitely affected me. When people say, oh, horror movies, they don't really affect people ... [laughs] they totally do. I don't believe in censorship obviously, but gosh. Aiyiyi.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_SeiFJ_biSc&feature=youtu.be

Well, it's like you read those Grimm Brothers stories. They are incredibly gory sometimes. I read them to my daughter, and sometimes I feel like, why did I just read that? I should not have read that.

Oh my god. Do you change the words? Sometimes, I'll be in the middle of reading to my daughter—my daughter's four—I'll be in the middle of the story and I'll just change it as I'm reading it.

Oh, totally.

Because I can see it's just too fucking dark. Especially if you're reading an original or where they're trying to adhere to the original version of Little Red Riding Hood.

There's a lot of anti-Semitism that I have to gloss over.

Are you serious?

Oh yeah, in the woods, there's often an evil Jew...

Which ones are you reading with the anti-Semitism?

I'm not thinking of the Grimm Brothers now, but the ones from Andrew Lang, like The Red Fairy Book, The Blue Fairy Book, etc.

I haven't seen those.

They're good! But you have to be careful.

Oh my god.

There's other stuff in those fairy tales, too, where, you know, parents agree for their kids to be slaughtered in exchange for some kind of magic reward [Harkham laughs] and things like that.

Yeah, and a lot of the happy endings are like, Hansel and Gretel got back to the house. Their evil stepmother had died. [Hodler laughs] Not that she was forced to leave. She just died.

And their dad loved them. He didn't want to go along with the whole leaving them in the woods thing. He loved them for real.

I know. Just trying to explain that concept. Not even explaining, because you're kind of just going with the story. Because there's no food in the house, they decided it would be better to get rid of the kids so that there was food for the adults. It's like they never even thought of this idea. They don't live in a world where there isn't enough food for everyone and decisions have to be made like that.

I think that might be one of the things those stories are for, like horror movies. They're a way to safely introduce you to —

To experience trauma.

And to learn about some of the less pleasant realities of the world.

I mean, Little Red Riding Hood. For a year, I was telling my daughter that story every night. She loved it. She liked how scary it got, and I think it's really cathartic in that way, but I don't think watching Toxic Avenger at 6 years old— [Hodler laughs] That's bad. That's so bad.

You might be right.

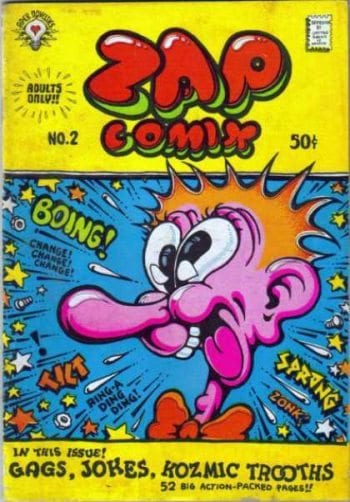

It's not the same. So there's a lot of that stuff, and I did discover a lot of comics at that age. My oldest brother, he's a guy who draws and paints, so there was all kinds of alternative comics lying around his room. Now he doesn't really read them, but it was amazing to just to look at issues of Zap or stare at those comic book covers like Cheech Wizard and try to understand them.

[Laughs] Yeah, it's so weird, but you know when you're little, you're like, where are his eyes? Where are his hands? [Hodler laughs] How does he walk? Because it looks like Disney. The culture always has nostalgia for twenty years before so in the '80s there was nostalgia for '60s stuff, in the '60s there was nostalgia for pre-WWII stuff. So there was all that in early underground comics. All the stuff looked really polished. Theres this issue of Zap with this really goofy-looking guy on the cover. It looks like a Disney comic. When you're young, you don't understand the context. I remember reading that comic and I think "Joe Blow" is in there and I thought it was so evil. So my whole perception of alternative comics is that they were sick and confusing. Looking at a Jim Woodring cover at 12 years old is just confusing in a great way. And I related them to punk rock because my brother would have Reagan Youth and Agnostic Front records side by side with the comics, and all those images were just confusing to me. I would stare at them and just try to make sense of them. Comics were just folded into that for me.

What did your parents do when you were a kid?

My mom was taking care of all of us, and my dad was in garment manufacturing from the age of 13. That whole industry has completely changed. He was working for a dressmaker as a kid at 13. I think the revolution in Baghdad happened in the early '50s and there was a lot of antisemitism when that happened. This was after the formation of Israel. This is stuff I only learned while researching stuff for Blood of the Virgin. In the last issue, I had some Sephardic Jews talking, so I actually went and researched this. My dad's not a great communicator, so I couldn't get facts out him. Basically in the early '50s, after Israel is formed and Zionism is kind of a popular thing, any time there's hardship in any of these Arab countries, they blame it on Jews. And then there were people trying to overthrow the government, and they blame that on Jews. Both factions who were trying to get control of Iraq at that time would blame the problems on Jews. There was a lot of stuff like that. And so a coup happens in the early '50s, and Jews basically get kicked out of the country. It became very unsafe for Jews to live there. My dad's family—he's about three or four—they all move to Israel but Israel isn't really prepared to accept refugees properly-these people all had to leave everything in Baghdad, so they came with nothing.

If you talk to Sephardic Jews, you hear these stories, it's like a regular thing, and it’s still raw for them. They got put in refugee camps. So my dad lived in a refugee camp for a couple years. He had seven siblings and his parents in a tent. I think that's all the drive you need to try and get something going. And then some family member lived in Australia and so they saved money and they sent him. He's 14, they sew $4000 into his pants so he won't lose it, they put him on an airplane—never been on a fucking airplane—he goes to Australia where even today it's a pretty racist country. There's definitely a sense he's the Other. I think he tried to go to school but I don't think he ever really went to school. He doesn't like to say it because I think his goal in life was to be like a normal white person. So he married a white girl from New Zealand who had never met a Jew until she met my dad.

She converted because he wanted her to, and she didn't know what that was at all. ... my dad doesn't know this story but he's not going to read this interview, and this is funny. He asked the local rabbi in Sydney, Australia: "My girlfriend's going to convert. How do you do it?" "Well, she should live with a Jewish family for six months, and she should learn all the customs and the lifestyle and the ways it's done." And she's like, okay, and moves in with this family. and right away when I hear this, I'm like what's the story there? that doesn’t sound right to me. and she at the time would have no idea what was normal or not, and neither would my father. She was very young, she was 17 years old. So she moves in with this family that had other girls going through the conversion process as well also living there, and she said the rabbi who lived in the house tried to get into bed with her.

Whoa.

At like eleven o'clock at night. And she yells, "Get the fuck out of my bed!" And I asked her, did you really say that to him? Did you really? And she was like, yes, what are you crazy? [Hodler laughs] So I'm like okay, fine. Did you tell dad? No, I did not tell your father because he probably would've driven his car through the front of this guy's house.

Yeah.

He would have been super upset. And the guy had been helping convert non-Jewish people into the religion for the last ten years. he eventually got caught doing something and they kicked him out of the community. but that was her first experience in a Jewish community.

Was she Christian before that or something else?

Not really. They would go to church for the social aspect in the tiny town she lived in. My mom grew up on a dairy farm, where her mother was the housekeeper of a farmer who was a widower with a bunch of his own kids. So he let this divorced woman, my grandmother, live there with her kids, and they all worked and live on the farm as a form of payment. They weren't really religious, but in a small town in New Zealand, Christian values would have been the norm, it would have permeated everything. The Mormons were nice to them. They would come to the farm and give them chocolate and would try to take them to church and stuff like that but there wasn't a big religious culture for them— or my dad. On my father's side it was just traditional, so they were about equal.

So then they moved to California before you were born?

They were living in Australia. They had one kid in the mid '70s and then they moved to L.A. because he thought he could get some work there. They had been to L.A. briefly the year before and that led him to believe he could find work if they moved there. He thought they'd go to L.A. and get something going. His brother owed him some money so he arrived with nothing and kept expecting some money to be wired to him, but his brother never sent him the money. He was totally broke. Someone from the synagogue lent him $200. To this day he's still friends with that guy.

It's a good reason.

Yeah, right. And then me and then the others ... everyone just starts coming out.

Is your dad still working in L.A.?

Yeah, he is.

What do your older brothers do?

They work with my father. Nothing exciting.

And your younger brothers and sister?

One works in education. Another in real estate. That's basically it.

Are you guys close?

Yeah. I suppose. We're all pretty much in Los Angeles. With Jewish holidays as you know you alway have an excuse to see each other all the time. If anything you have to make excuses to not go to things.

It sounds like your older brother was into art when he was younger, but otherwise you are kind of unusual in your family in that regard. Is that right?

Well my older brother is a painter. He doesn't have a fine arts career, but he's serious about painting, and when I was younger that was a big influence on me. Because my dad was working all the time and I didn't see him very much, my oldest brother, who is eight years older than me, was very much the father figure. So in that regard I must have realized that it's a natural thing. I'm seeing comics, I'm seeing art, I'm seeing all kinds of cultural stuff. His room was a kind of guiding light. I put importance on that because he was important to me. It doesn't come out of nowhere. That's probably a big part of it.

Well my older brother is a painter. He doesn't have a fine arts career, but he's serious about painting, and when I was younger that was a big influence on me. Because my dad was working all the time and I didn't see him very much, my oldest brother, who is eight years older than me, was very much the father figure. So in that regard I must have realized that it's a natural thing. I'm seeing comics, I'm seeing art, I'm seeing all kinds of cultural stuff. His room was a kind of guiding light. I put importance on that because he was important to me. It doesn't come out of nowhere. That's probably a big part of it.

When you go home and you're visiting with your family do you talk about Kramers 9 coming out or the new Crickets or whatever? Do they understand it?

I don't think my parents have read it. Any of my work.

Really?

Yeah, my identity is not formed by my work in their eyes. They just go, oh, he draws, he makes stuff. [Hodler laughs] Why doesn't he make more money? Can you sell comics? There was a New York Times review of Kramers at one point. They pay attention to that. There was an L.A. Times article, they pay attention to that. They don't really read the work. But I don't send them links, I don't give them copies. I try to sort of keep my parents in the loop, but it's more self-serving than having a desire for them to read my work. There's that element in myself that I'm trying to kill that needs to be validated by my parents. I really hate that part of me. You can't really impress your parents that much with this stuff because all they want to know is, did you get a good advance? [Hodler laughs] I've been saying about Blood of the Virgin for eight years, that when the book's done, it will come out, it will be a book, but my dad just thinks I must be doing something wrong. Because he's like, you should get an agent and you should sell someone this as an idea. He looks at The Simpsons and he's like, "Just do that. Can't you do that?" And I'm like, well, it doesn't really work that way [laughter] and also I have no inclination to do that. But you know, it's fine. It doesn't bother me. I talk to other cartoonists and I am always surprised to learn they are holding something back, or even the idea that they are encouraged by their parents.

You said you had no interest in doing The Simpsons, but you went to CalArts to study animation, right?

I did, but you know, it's logical when you're in high school, you're making zines, you're drawing comics, you apply to art school. And I was somebody who was interested in so much when i was a teenager. I was dabbling in every form except for music. I was trying to do everything. I was doing school plays and I was doing gig posters like I said before. I was interested in so many different fields. And the experimental animation department wasn't just filmmaking, it wasn't just animation, it wasn't just drawing, it was everything. They didn't have a comics program but they had all these different things I could explore. But I very quickly realized that everyone who made these beautiful short animated films could only really show them at festivals and then use their film as a business card to get jobs applying their style to doing insurance commercials or Red Bull commercials, and that was really unappealing to me. I really didn't want to do that and I naturally doubled down on comics. I think at one point I was working on Poor Sailor and I showed it to my mentor, the person they put in charge of you, and she thought the strip was really nice and that I should animate it and that's when I realized this isn't a good fit any more. But it was a good school. It was useful, I guess.

AUSTRALIA

So when you were 14 you moved to Australia... Was there a reason for that? [laughs] I mean, obviously there was a reason...

No, you know, I never understood it, because when you're young you just do what your parents tell you to do. Supposedly, and this may not be true, my dad was really keen to move back to Australia so he asked my mother—who he'd already been divorced for five years from at that point—to move the family back to Australia. And she said, “Okay.” [laughs] Very weird. And then he didn't go. She had somehow organized a house to rent and he said, "I'll be there. You set it up. I'll be there in the middle of the school year." And then basically we didn't see him for two years. He visited every five or six months and was completely freaked out by his kids going through puberty. My two older brothers didn't go. They stayed in the U.S. After two years, I think, he came to visit. I think he caught my younger bother smoking pot. I was sixteen, my brother was 14 and my dad was like, all right, this is done. Forget this. But it was very good for me.

In what way?

Because in Los Angeles I was very much alone, socially. I had my older brothers, and I could go through their tape collections and I could go through my brother's comics and there was a lot stuff in the house, but I never had friends who who dug any deeper than the most generic pop culture. At that time I was reading Image comics and segueing out. So going to Australia ... I remember being shown to my locker and the guy with the locker above mine had a picture of Jimi Hendrix in his locker, and that would have blown my mind a little bit. he became one of my best friends. And through him I met other people my age who read books and were interested in Monty Python and reading books.

It's funny you had to go to Australia to find kids who shared your interests.

Yes. But it was less shared interests and more that they pushed me intellectually, they were into unpopular stuff for weird reasons… What's the name of the Peter Sellers radio show?

The Goon Show?

Yeah, The Goon Show. Fourteen-year-olds listening to The Goon Show and talking about post-War English humor. Or to learn about Carlos Castaneda. That was the right age for the next level of that. And we all did it together. We were trying to reach beyond our intellectual means. half the music we listened to was jazz, and the books were old Mervyn Peake hardcovers and Dylan Thomas poetry books, and that's good at that age, to be pushed to that kind of level. So Australia was great for me at the moment. Because if one of your friends is really smart, it ups everyone's mental game. Did you see that amazing Noah Van Sciver comic? About when he's a teenager? My Hot Date?

The comic is great, but one thing I really took away from it, he's trying to fit in with his friends. They are all listening to Korn and Limp Bizkit [Hodler laughs], wannabe white skater kids trying to get dreads and silver beaded necklaces. This whole scene that I would see peripherally as a teenager and was happening concurrently but I never had to ever try and be a part of, thank god. I mean literally the most embarrassing thing I was probably into at that age was really loving Bukowski.

Right.

Like really loving Bukowski. [laughs]

You know, it's a phase to go through.

Yeah, it's a phase. I was in eighth grade reading Ham on Rye. I mean think about what that looks like. That is ridiculous. I was saying to my mom the other day the only book in our house and in every other house I ever walked into growing up was Leon Uris.

[Hodler laughs] I had a feeling you were going to say that!

Remember that book with the dagger on the cover? That book was in everybody's house. Every Jew had that book in their house. Just that one. I don't know why. That guy Leon Uris had the market cornered for people who don't read but need one book to place on a side table. Anyway, the Bukowski stuff was ridiculous, because it's all very romantic at 14.

Yeah, but if you see a kid who's 14 years old reading Ham on Rye, you know that kid is probably going to turn out to be at least ... engaged with things.

Yeah. And I had good friends, and for the most part I think it was pretty good. The only stuff I look back on with horror is the LSD.

What do you mean?

Taking LSD at 16, wandering around downtown at 3 in the morning without any shoes on—that's fucking crazy. But besides that it was all pretty wholesome, because me and my friends, we wanted to have moral fortitude. We didn't want to be creeps. Like if anyone talked about masturbation, we were like, oh my god! [Hodler laughs] We weren't gross. We wanted to be upstanding people. Which is funny at 15 to want to be an upstanding person, whatever that means. I think we all hated school and getting on a school bus and kids yelling at us and grabbing our books and knocking them out of our hands [laughs] or ripping up our comics. But it was good. It is funny, a lot of cartoonists I talk to have had very similar circumstances. I was talking to Kevin Huizenga and I just assumed Kevin was surrounded by weird Dutch Christians [Hodler laughs] his whole life until like 2008. I swear to you I always assumed that until he met Ted May and Dan Zettwoch in Saint Louis that he was just surrounded by Christians. But then he was telling me recently that in high school he had six people, and they had their own newspaper. I'm sure it's like that for a lot of people. Australia was good in that regard.

Do you miss Australia at all? Do you go back?

We go back a lot because my wife's from there and I have a couple friends there. I like it fine. I can see moving back there. It's nice and quiet.

FATHERHOOD

You got married pretty young, is that right?

I did. I was religious at the time. My wife wasn't [laughs] but I convinced her to marry me. It's insane. I think it's connected to being a cartoonist: supreme optimism in the face of actual reality. You just think everything will be fine, I can do it all. Being married at 24 was very much like that, and also it felt like the real thing to do. Because it was uncool. Who gets married at 24? It's fucking stupid. I do that. I don't need other things, I know what I'm doing, and now in hindsight, I literally can't think of my twenties without cringing.

But it worked out, right? I mean, I don't know... [laughs nervously] I assume?

My marriage is doing good and I love my kids and everything is cool, but at the same time I look back and I see a lot of lost opportunity. Because you get married that young and you have kids that young and it puts a financial burden on you when really, if I didn't have children, especially in my mid-twenties, I could've just been drawing comics.

Did you read Joe Ollmann's Mid-Life?

No. Is that the one were the guy gets picked up by the UFO?

No, this one is semi-autobiographical, I think. It's funny. The main character had a kid when he was really young, like 19 or something.

Right. He's got a full-grown daughter.

Yeah, and then he got divorced and remarried, and then in his early forties right after his kid finally left home to go to college, he had a new kid and started all over again.

Oh my god. That's like my nightmare. [Hodler laughs] I mean, the thing I pine for is emptiness. I pine for no phone calls, no one asking for me, no one needing me. Because I locked myself in. And obviously you have ... two kids?

Just one. [Two now.]

Just one. But you know, you're locked in. People rely on you and it's very difficult. they need you. which is vaguely heartbreaking to me. Raymond Carver was tasked to write an essay about what inspired his work and he remembers being 33 on a Sunday at 2 pm in a laundromat watching his clothes go round and round, and having one kid at a party and another kid who had to get picked up from somewhere else and thinking what the fuck has happened? [Hodler laughs] I'm stuck and I can't get out and he said he'd never felt more defeated in his life. He also had kids very young, and he and his wife yearned to be free from the life that they lived. They moved every six months to a year for twenty years, he was just all over the place, trying to keep his head above water, and he talks about how because of the kids, short stories were the only form that made sense. Because of kids he had all these pent-up emotions, either feeling resentful or lost opportunity or ambitions, basically all these things. So his kids were his inspiration. Not in a cheesy way but in a real way. And I thought that was amazing. I think it's really true for most people with kids who are trying to make work.

How did having kids affect your work, do you think?

I think I'm always like ten years behind whats actually happening to me, as far as it coming into my work. When I started doing Blood of the Virgin, my oldest son was ten months old, so I made the baby ten months old. And now he's ten, and the baby in the comic is still ten months [laughter] and so enough time has passed where I can sort of look at that relationship in the comic with distance. Those scenes are a little different now, the scenes at home.

You might have heard this before but Peter Bagge (I think) once said that his Buddy Bradley stories were usually about things that had happened ten years earlier. He had to wait a decade before he could write about them.

Yeah, because you don't really know it when you're in it. How can you? You’re just following impulses. I guess Crumb was always good about writing about his life as it was happening. Maybe that's not true, maybe he was always writing about the past too? Now that I think about it.

It depends on the story.

It makes sense. How can you write about the present moment with any distance when you're having kids, living your life? It's such a whirlwind. With a long-form story you start working on something because you have these impulses towards things, and then as time passes you start seeing with a little more clarity whats behind those impulses and how to further those ideas, hopefully without killing it by knowing exactly what it is. You start seeing these connections that you didn't notice initially and your own life plays a big part in that.

Are there any connections you could think of off the top of your head like that? That you noticed later?

[Pause] I can't go into it.

That's fair.

All I can say is that Blood of the Virgin is not written out as a script. It's worked on scene by scene, so it can stay fresh. Old ideas can be tossed for new ideas. For whatever reason, the broad strokes of what constitutes the plot came easy so I have a framework with which I can follow my interests without losing sight of the whole, but without limiting it or knowing what the book is in total. At some point I realized the story should diverge a little and go in this other direction for a little bit and for the longest time, I didn’t know what the connection was between the two strands. I don't know and it might ruin the book. [Hodler laughs] As time passes you start thinking about your own life in relation to the strip and you can see what's working under the hood about these ideas, whereas before it was all just following what felt right. I try not to know too much. I think it's bad to know too much, because then you sort of just end up slotting in ideas. For example you could be working on a scene, not sure what the specifics of the dialogue should be, and if you know the major theme of your book is “fatherhood,” you logically think, “They should talk about fatherhood." In a bad book, you finish it and it's like a perfect train track with no gaps, and it's just perfectly filled in, and ideally you want to have some element of tension and mystery from which you can't piece it all together so neatly. So when you're making something, you can't know all of it. You can't because then you're just answering questions.

Do you know how long it's going to be?

I'm in the second half.

Do you have a vague idea of where it might end or not even that?

I know the overall plot and thats been there from the beginning. I could tell you over dinner the entire story in broad strokes, but the meat and potatoes of each of those ideas can end up being anywhere from a panel to twenty pages. Elaborate scenes I hold in my head for five years can end up not working once I finally get to them, and they end up being one panel. And on the flip side, something I think will be a page can grow and grow into its own chapter. Blood of the Virgin was originally conceived as a short story. Then I thought it would be three chapters total. What is currently issues 4 to 6 of Crickets was thought of initially as one 24-page chapter. And I still feel like I am doing it as economically as possible-I try not to waste space. So while it's taken many years to get the first half done, I am hopeful I can finish it soon. What it all comes down to is turning off all the noise and having the financial stability for a couple months to just think straight for a minute and get into a rhythm. I've gotten into a pretty good system where a page that used to take twenty hours to do can be done in less than half that without cutting corners. Going to Australia for 2014 and only working on this comic was such a good thing because it made me really break through my own process. I had nowhere else to go, I had no distractions, I couldn't do anything. I had to just buckle down and do it. So now when I sit down, I know how to do it. 2014 was all about learning how to draw comics. Most of that material is in Crickets 4 and part of Crickets 5 because it's drawn out of order. I talk to Kevin Huizenga fairly regularly. We've been talking for over ten years, and the issues we had when we were in our mid twenties were literally the mechanics of cartooning were impossible to figure out. And then what happens is if you keep doing it you develop what Kevin calls "systems." You start understanding how it works, how to do it, and your struggles aren't "I don't know how to draw a page of comics." You can do that. The writing remains the difficult part, and is the thing that holds everything else up. It’s a matter of doing a page that's deeply felt, so it's not just tossing off material. That's a long answer to say that I think I want to get the strip done in the next two years.

Oh, I didn't realize. That's pretty fast!

Oh, I didn't realize. That's pretty fast!

Ideally what I would like to do is two more issues. There isn't that much left, but they're big chapters, so each one ends up being about fifty pages.

Yeah, you could do it!

Yeah, you could do it. [laughter] It's almost over, you could do it. Ten hours a page means that if there is nothing else that you have to deal with, you can do two to three pages a week, and the thing is that when you're working on comics, that part of your brain gets strong, so it becomes easier the more you do. I never think of the whole book beyond its most basic shape, because if I think of the whole, I get overwhelmed and i start questioning the scene at hand. It got difficult in the middle of Crickets 5. I started thinking, shit, we're in the middle of this now—I have to start connecting the dots. And you know, the first half of the story is all expanding—in dramatic storytelling, not necessarily in literature. A lot of dramatic storytelling is building, and you're sort of expanding out, and the second half you're mirroring or going back in on what you've already established. Blood of the Virgin is designed more like prose fiction—it's not a movie in comics form—but still you do start thinking, what does the book look like?

What I learned was that while it's good to know where I'm heading on the macro level, and to have those anxiety attacks every once in awhile, it's best to focus on whatever single page is in front of me and nothing else. And put all my attention on to that single page like my life depends on it. Not in the Wally Wood or Jack Kirby way of the splashiest page, but just the best version of that page. So if you need a scene of somebody waking up and going to the bathroom and brushing their teeth, you try to give it everything. And then it starts helping the overall rhythm. There's the internal rhythm of reading, of writing a story, of working on a story in order, so when you have a slow silent sequence that goes for five pages of him driving his friend home at dawn, you know what needs to come right after that tonally and rhythmically. You go, oh we've just done this whole thing over months and months, I want to have a vulgar joke right after. I don't know what it'll be, and I don't know who will say it, but I want the word "butthole."

How is serialization affecting all this? Are the chapters that have already been published—the ones from Crickets 3, 4, and 5—locked in? Do you plan to go back and change them when you put together the book?

I may add standalone things between chapters. as to whats already been published, I’m not going to change them drastically. I will try to just fix the things that are too terrible to ignore-some lettering for instance, a terribly drawn car or an expression on someones face. I had to look at Crickets 3 while working on Crickets 6 to see how certain characters and rooms looked and it was physically painful to look at. As to serialization, I initially wasn't going to serialize Blood of the Virgin. After issue 3, the plan was to finish it and release it as a book. But it just kept growing and it kept getting longer and I felt like I couldn't not exist as a cartoonist for the next however long i need to release this. I had to release it in some way as it might take years. And so then you realize that there's two paths for what you can do. You can make a great overall packaged thing where it's like Rubber Blanket or Eightball, where the chapter is perfect, there's a short story, there's a gag, the letters page is solid. Dirty Plotte was always that. Doucet serialized My New York Diary; there'd be a dream comic, a one-pager.

I think New York Diary works better serialized.

I think New York Diary works better serialized.

Well, there you go. Jim Woodring, obviously. Frank. There's that model. If you haven't released anything in two or three years, you want the next comic to be really good. you figure, it's been a long time, but l will try to make it great. And it's also expensive, they aren't cheap. It's going to be 7 or 8 dollars. That's one way. But then on the other side of it, there's the Underwater/Yummy Fur model, the Louis Riel model, like, okay, we've hit 22 pages, I don't care if we're in the middle of a fucking scene, the issue's done. Which is great too, but what you're saying is this issue may not stand on its own but hopefully you'll be doing it every three or four months.

I'm trying to do something between those two models. I don’t want to draw any other comics till this strip is done, certainly nothing substantial, so I can’t make what I think is the ideal comics package. the best thing about serialization, is that it puts your feet to the fire with every single chapter. I feel like I have to make each issue as good as I possibly can, because its being judged on its own merits and not as a whole. I don’t know if the chapters would be the same if they only came out as one larger book. Plus, and this is a big one for me, I love single-issue comics because comics are quick to read so you can really absorb and cherish a chapter while waiting for the next one to come out. David Boring chapters 1 and 2 immediately spring to mind, but there are a lot of comics like that for me, strips that benefitted from a lot of re-reading. I really love the format.

The story is set set in the '70s in a kind kind of Roger Corman-esque filmmaking milieu, but it seems like it mixes stuff about your family transmogrified into other characters. Is that right?

Yeah, thats true. I'm trying to just bring my interests into this thing and that's why it keeps growing. The strip was initially inspired by my parents and their lives in very sort of hollow way. A lot of that’s evolved, but that was the initial spark. This strip was meant to be short but the framework of the plot kind of invites all this other stuff to glom onto it.

I mean, basically one of the things that sparked the story — I'm a little hesitant to talk about it, because it's a work in progress, but my dad would talk about coming to L.A. with his wife and young son, and just struggling to get something going. he would tell me these stories about going to a meeting and pretending he had a driver to make it sound like he had a successful business—when he really he had taken the bus. And they would walk him out of the building after the meeting, and there was no car waiting for him, and he'd bluff, "Oh, my driver must gone around the block. I'll wait." Stuff like that, which I thought was so funny, and then at the same time my mother would tell me, "Yeah, I tried to leave your dad. I tried to escape." [laughs]

So it's an interesting thing—the guy's professional life was expanding out, but his personal life was so bad, and I thought that was really funny, and I thought there was enough tension there that I could really dig into this. I'd never done a story set in Los Angeles so that become another interesting element, visually and narratively. The only thing that didn't make sense to me is what the character did, because my dad didn't work in film, and I didn't want to make it the clothing industry because I couldn't get a sense of what it would add. Movies is such an LA thing, and it sucks how much Los Angeles culture lives in the shadow of movies, but that setting worked for this. I know there's a lot of fiction and a lot of movies about making movies, but—I know you and I both read Video Watchdog--

Sure.

I was discovering Video Watchdog around this time. They would run these old bulletin reviews for a regional exhibitors newsletter written by Joe Dante before he was a filmmaker. First of all, I'd never heard of almost any of these movies. And I thought what a weird subculture, where all these movies and all this stuff is happening in the fringes of this industry. It's charming for all the obvious reasons. You watch a movie like Eegah! You know Eegah!?

Sure.

With Jaws [Richard Kiel]. You look at that movie, the guy who made it put his son in it because he wanted him to be the next Ricky Nelson, and it’s about a cave man in Palm Springs. It’s great on many levels. You read these stories of these people and I can’t get enough of it. The strip is not love letter to that stuff. I'm not trying to make something that's reverential. I just think it's a really good setting. Probably this is where it gets a little tricky for me to think about. I come from a big family. I've been locked in a family world my whole life. And movies are very much about families, these big networks of people that you cant escape from. So it just seemed like a natural thing, and it didn't feel like I was stepping on well-worn territory.

Right.

Now I do, because I didn't even know how much fucking stuff is out there.

Did you ever see The Stunt Man?

No.

The Richard Rush movie? You should watch that, it's good. He worked with Roger Corman.

Oh yeah, I know of it. It played last week at the New Beverly but I missed it. I need to see it.

Something occurred to me which might not be what you were thinking at all: during that Roger Corman era, all these people like Joe Dante and Peter Bogdanovich and Francis Ford Coppola were doing these schlocky things with him, but they had the ambition to be great artists and make personal movies ...

Absolutely. The rise of the monster kids. They call them monster kids. It's a whole culture of people who grew up watching these movies late at night on tv, because the monster movies were packaged and sold by Universal and whoever owned RKO, pre-sold as packages. They would have a local host, and all those kids who grew up loving that stuff in late '50s, early '60s, in the '70s they grow up to be the first filmmakers who don't feel like they're slumming it making a horror movie. When Joe Dante makes Piranha, he's excited to make Piranha. Whereas you look at Byron Haskin, the guy who made Robinson Crusoe on Mars, that's like the end of your career. In the '50s and '60s, if you're making a horror movie or a science fiction movie, unless it's the occasional marquee movie A-list movie like Forbidden Planet, you're slumming it. You're at the end of your career. that’s a little simplistic, but you know what I mean. Their goals were to make “respectable" Hollywood movies. But these guys in the '70s, they were all into it. I think that's interesting. They're like a generation of people who don't see this as trash. And there was another idea, these people, what are they escaping from anyway, where they have to stay locked into their childhood. What is that? Where they're constantly trying to escape into the past.

Do you think that's true of just those kinds of artists, or all artists?

Well, I don't think it's true of filmmakers for the most part. but with those filmmakers, you have guys who are unabashedly into genre movies. Really, that's a first, so that's interesting to me. Beyond that, we now have a culture where superhero movies, Star Wars, fan fic, it’s all taken over. I mean, Game of Thrones gets recapped in the New York Times. A show about a fucking dragon. [Hodler laughs] A bad show about a dragon. It's so stupid, the culture. I was reading Cannery Row and at the end of Cannery Row, a hobo recites a poem to a room full of hoboes, and they all know the words to the poem. That is so far-fetched in today's world ...

They'd do the Green Lantern oath and they would all know it.

Exactly right! And it's not that I am disgusted by mainstream culture. I genuinely haven’t cared about popular culture since I was probably 13. But look at what these guys have wrought upon the world. People are just so obsessed with their own monuments to, like, He-Man. [Hodler laughs] It's insane. Modern man is a boob. So in that regard that's another reason why Blood of the Virgin is not a love letter. As to the idea of specifically artists trying to escape into their work, well, I think I started Blood of a Virgin interestingly enough when the first Walt and Skeezix book came out. Jeet Heer has an essay in that book where he talks about Frank King’s life while doing the strip. His son at the time had been sent to a boarding school, he didn’t get on well with his wife, and you can just see this guy used his strip to live in an alternate universe. Certainly a thing that happens with cartoonists. I have experienced it myself. So that's an element in the strip. Every Kim Deitch book ends with the main character realizing that this whole world that they're obsessed with can't go on existing any more, that the pygmy village has to be destroyed. This is a thing for cartoonists, and I think it's likely true for novelists. I don't think it's true for filmmakers and musicians because their work is so much more collaborative.

I think too for a cartoonist, it takes so much time, and if you're going to spend years with the same characters in the same place, especially if you're doing a strip that lasts for decades, at some level it's going to either start to be appealing to you or it will change to become a setting that's appealing to visit for you.

For sure. I always want to ask Jaime Hernandez, does it bum you out that Maggie's not real? Does that freak you out that she's not here?

[Continued here.]