“I’m fine. I’m just ... constipated.” -- Rod Vanderbranch in Nick Maandag’s The Libertarian (2012).

Some cartoonists are wet, others are dry. The wet cartoonists gush out images, their pages overflowing with decorative flourishes, free-flying emanata and gratuitously juicy “chicken fat” (to borrow a useful term from one of the wittiest and wettest of artists, Will Elder). Aside from Elder, the pantheon of the wet includes Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Lynda Barry, and Julie Doucet. Conversely, dry cartoonists achieve their greatest effect by a rigorous process of visual dehydration (comparable to the powered crystals developed by NASA to feed astronauts). To get dry art you have to squeeze out any extraneous detail unnecessary to the core message conveyed. Prime dry cartoonists include Otto Soglow, Ernie Bushmiller, and Richard McGuire.

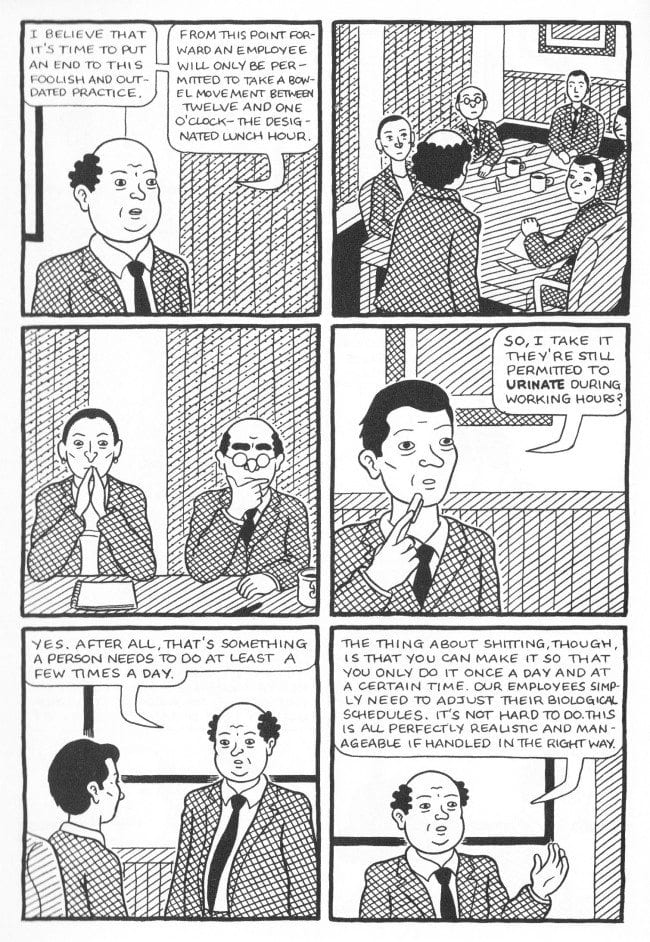

Nick Maandag is not just dry, he’s constipated. Visually, there are very few gifted cartoonists who are as remorselessly ungiving as Maandag. His characters are Mr. Potato Head assemblages: oval faces distinguished by clumps of hair (various characters are set off by a bush growing along a bald pate, a goofy sideburn, a pair of Groucho Marx eyebrows, a wax mustache). These puppet-people inhabit a sterile, scrubbed, denatured post-industrial landscape of strip malls and office cubicles. Even the shading in the art – usually expressed by slanting lines that never let us forget that a ruler is being used – reinforce the fact that we’re reading about a world that is mechanical rather than natural. There is no succulent texture in Maandag’s universe, no oasis of exfoliating leafy beauty to offer relief from the aridity of the art.

Maandag’s visual constipation, the withholding impulse or willful stoppage that is evident in every panel he draws, turns out to be an apt counterpart for the story he tells in his new book Facility Integrity [Pigeon Press, $10], a delightful satire on corporate culture detailing the ill-fated attempt of Azwype Inc. to regulate the bowel movements of its employees. An office comedy (or cubicle caper), Facility Integrity gains its edge from the very dryness of Maandag’s art. The fact that his characters are affectless even while being mercilessly demeaned bolsters the satire. The few moments of shame – usually displayed by an almost throw-away blush or a moment of silent awkwardness – are all the more powerful for being so subdued. Without spelling it out, Maandag has created a world where decency is mute: an indictment more damning than a manifesto.

Maandag’s visual constipation, the withholding impulse or willful stoppage that is evident in every panel he draws, turns out to be an apt counterpart for the story he tells in his new book Facility Integrity [Pigeon Press, $10], a delightful satire on corporate culture detailing the ill-fated attempt of Azwype Inc. to regulate the bowel movements of its employees. An office comedy (or cubicle caper), Facility Integrity gains its edge from the very dryness of Maandag’s art. The fact that his characters are affectless even while being mercilessly demeaned bolsters the satire. The few moments of shame – usually displayed by an almost throw-away blush or a moment of silent awkwardness – are all the more powerful for being so subdued. Without spelling it out, Maandag has created a world where decency is mute: an indictment more damning than a manifesto.

Facility Integrity is rich in treats. Maandag does a pitch perfect parody of the jargon found in the corporate world: the bullying bluster of the CEO addressing cronies, the slippery euphemism of memos, the gung-ho pep talk of a shareholder’s meeting (“In the fourth quarter we prioritized our pursuables, pursued our priorities, penetrated our eligibles, and rammed our desirables!”)

The ritualized social interactions within the corporate hierarchy are examined with anthropological coolness: the CEO Mr. Aswype is not just a nastily domineering but also a figure of pathos because he is cut off from any frank and honest communication with other human beings. His underlings are mostly apple-polishers but one of them (Bobby Dextrose) is also being groomed for leadership, so acts like the cock of the walk. A middle-manager peeps over a cubicle divider, embarrassed at explaining the new policy limiting the period employees will be allowed to defecate. The employees (nicely described as “associates” – a common bit of corporate blather) hate their job but their resistance takes the form of futile fantasy (buying lottery tickets) or inept attempts to work around the rules. In sum, we’re giving a harrowing picture of a hellish social structure almost without hope (it is notable that the one figure who does fight back is an outsider, an immigrant from an unknown land with no ties to his fellow workers).

Whether consciously or not, Maandag is pursuing a Freudian argument in Facility Integrity. As Freud taught, miserliness is an outgrowth of the anal-retentive stage of development. The hoarder or compulsive collector is one who wants to gather up money for himself or herself, just as children at certain age try to hold in their feces. Aside from Maandag’s work, this argument can be demonstrated with other comics: it is no accident that Joe Matt (an anal character on many levels) is both a miser and avid collector. One of Matt’s quirks is that he urinates in a jar – a liquid counterpart to anal-retentiveness. In Facility Integrity, there is a Freudian overtone to the characterization not just of Mr. Azwype but also Bobby Dextrose (whose mixture of brown-nosing and cockiness is mirrored by his engagement in sadomasochist domination sessions) and also the employees of Azwype (whose mindless purchase of lottery tickets and escapist desire to hide-away in their bathroom stalls is the inverse of anal-retentiveness: their bowels and their finances both being out of control).

Not only is Maandag’s particular style well-matched for this type of nose-thumbing at corporate culture, but the more generic property of comics are equally well deployed. Within the main story, Maandag maintains a rigid grid-structure: six square panels per page, three rows with two panels each. This invariable structure is implicitly linked to a work rectangular environment of cubicles, desks, computer screens, floor tiles, and bathroom stalls. Only once does Maandag modify this cage-like pattern, on the last page in a stand-alone strip that offers a glimpse of Mr. Aswype's home life and relationship with his servant William. On this final page, we get a more generous twelve panels (four rows of three panels each): this doubling of panels is visually echoed by the bathroom tiles that serve as the background to the scene and can be connected to the implication that Aswype is freer with his bowel control when he is away from work (a fact that we can reasonably infer from the discussion of toilet stains in this strip).

I’ve been following Nick Maandag’s work since 2007. Aside from Facility Integrity, he’s done a string of self-published comics including The Experiment (2007), Jack & Mandy (2008), Nick Mandaag’s Laff Depot (2009), The Libertarian (2012), and Streakers (2011). His early work was callow, his propensity for absurdist mockery often leading him to go after his targets in an unproductively scattershot way. For example, the supposedly postmodern restaurant in Nick Mandaag’s Laff Depot had nothing in common with anything genuinely postmodern. In Maandag’s world, postmodernism means willful affliction of pain. In reality, postmodern art and culture is all too often complacent and indulges the audience. In The Libertarian, both the right-wing title character and his Marxist foils were mocked in ways that seemed arbitrary, blunting the parody. Yet even Maandag’s weak early work show a steady hand at structure and storytelling, which has served him well. Streakers was his break-through work, in part because he reigned in his absurdist impulses, giving us just enough wackiness to goose the story but not overwhelm it.

One of the remarkable things about Facility Integrity is that the story seems goofy but is actually quite realistic. A 2002 Boston Globe article on “the right to pee” describes many actual corporate policies that are all too close to what Maandag depicts: “In 1995, for instance, female employees at a Nabisco plant in Oxnard, Calif., maker of A-1 steak sauce and the world’s supplier of Grey Poupon mustard, complained in a lawsuit that line supervisors had consistently prevented them from going to the bathroom. Instructed to urinate into their clothes or face three days’ suspension for unauthorized expeditions to the toilet, the workers opted for adult diapers. But incontinence pads were expensive, so many employees downgraded to Kotex and toilet paper, which pose severe health risks when soaked in urine. Indeed, several workers eventually contracted bladder and urinary tract infections.” (This blog post by Corey Robin provides more context, as does this book by Marc Linder and Ingrid Nygaard).

In re-reading his work, it’s evident that Maandag has a tripartite division of humanity: there are the agents of predatory change (Mr. Azwype, Rod Vanderbranch, Henry the Pickle, Xavier the streaker) who impose themselves on the lumps of passivity (Jack in Jack and Mandy, Mr. Azwype’s employees, Sammy the Fish, Tim the streaker). As against both the predators and the passive, there are the liberationist agents of chaos (Mandy in “Jack and Mandy”, the unnamed immigrant in Facility Integrity, Doug the streaker). It is this last set of characters who provide the spark of hope in Maandag’s comics: unruly clowns who overturn the social order, unpredictable eruptive figures who usher in something new.

Dry though his wit might be, constipated as his art undeniably is, Nick Maandag is no partisan of the permanent status quo. He is an artist alert to the possibility of change.